From Prop to Producer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WP982.Pdf (1.640Mb Application/Pdf)

The Other Modern Dwelling: Josef Frank and Haus & Garten Christopher Long School of Architecture University of Texas at Austin January 1999 Working Paper 98-2 ©1999 by the Center for Austrian Studies (CAS). Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from CAS. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976. CAS permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of CAS Working Papers on reserve (in photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses; teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce Center for Austrian Studies Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promo- tion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota, 314 Social Sciences Building, 267 19th Avenue S., Minneapolis MN 55455. Tel: 612-624-9811; fax: 612-626-9004; e-mail: [email protected] A direct link to the CAS e-mail address cannot be included on this page, because it has been reproduced in Adobe Portable Documrnt Format (pdf) rather than html. We have done this because of the many high-quality images embedded in the paper. 1 In an article published in Der Architekt in 1921, the year when the economic and political fortunes of Austria finally began to revive, Josef Frank took time out to reflect on what the new realities of the postwar era would mean for the future of the arts and crafts in Vienna. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Krenek Ernest

KRENEK ERNEST Compositore austriaco naturalizzato americano (Vienna 23 VIII 1900 - Palm Springs, 22 dicembre 1991) 1 Allievo dal 1916 al 1920 di F. Schreker all'Accademia musicale di Vienna, passò poi alla Hochschule fur Musik di Berlino, dove continuò gli studi con Schreker, ed entrò in proficuo contatto di lavoro con Busoni, A. Schnabel ed altri esponenti del mondo musicale della capitale tedesca. Sposata la figlia di Mahler, Anna (1923) si stabilì in Svizzera ma due anni dopo divorziò e dal 1925 al 1927, su invito di P. Bekker, fu nominato consigliere artistico dell'Opera di Kassel, mettendosi in luce con numerose composizioni teatrali e strumentali ed iniziando un'intensa attività pubblicistica come collaboratore musicale della "Frankfurter Zeitung" e dal 1933 della "Wiener Zeitung”. Ottenuto un successo di portata internazionale con l'opera Jonny spielt auf, dal 1928 si stabilì a Vienna dedicandosi quasi esclusivamente alla composizione, anche qui a contatto con gli ambienti artistici d'avanguardia (Berg, Webern, K. Kraus). Nel 1937 emigrò in America, dove nel 1939 ottenne una cattedra nel Vassar College di Poughkeepsie, presso New York. Dal 1945 ha avuto la cittadinanza americana. Dal 1942 al 1947 ha insegnato nell'Università di Saint Paul, stabilendosi poi a Los Angeles. Dopo la guerra rientrò spesso in Europa, per corsi di composizione, conferenze e concerti. Musicista assai sensibile ai più attuali problemi estetici e di linguaggio, il suo arco creativo rispecchia l'evoluzione spesso contraddittoria delle correnti dell'avanguardia musicale del secolo. L'insegnamento di Schreker lo ha avvicinato nella prima gioventù ad una sorta di espressionismo temperato in senso tardo-romantico, ma ben presto si liberò da quell'influenza per avvicinarsi alle più diverse esperienze musicali. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

![Chapter 3 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3751/chapter-3-pdf-963751.webp)

Chapter 3 [PDF]

Chapter 3 Was There a Crisis of Opera?: The Kroll Opera's First Season, 1927-28 Beethoven's "Fidelio" inaugurated the Kroll Opera's first season on November 19, 1927. This was an appropriate choice for an institution which claimed to represent a new version of German culture - the product of Bildung in a republican context. This chapter will discuss the reception of this production in the context of the 1927-28 season. While most accounts of the Kroll Opera point to outraged reactions to the production's unusual aesthetics, I will argue that the problems the opera faced during its first season had less to do with aesthetics than with repertory choice. In the case of "Fidelio" itself, other factors were responsible for the controversy over the production, which was a deliberately pessimistic reading of the opera. I will go on to discuss the notion of a "crisis of opera", a prominent issue in the musical press during the mid-1920s. The Kroll had been created in order to renew German opera, but was the state of opera unhealthy in the first place? I argue that the "crisis" discussion was more optimistic than it has generally been portrayed by scholars. The amount of attention generated by the Kroll is evidence that opera was flourishing in Weimar Germany, and indeed was a crucial ingredient of civic culture, highly important to the project of reviving the ideals of the Bildungsbürgertum. 83 84 "Fidelio" in the Context of Republican Culture Why was "Fidelio" a representative German opera, particularly for the republic? This work has not always been viewed as political in nature. -

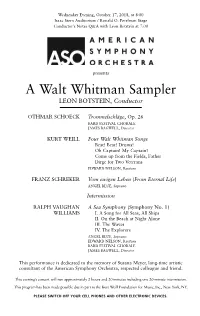

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

Claudia Maurer Zenck

Claudia Maurer Zenck Publikationsliste A: Bücher Verfolgungsgrund: „Zigeuner“. Unbekannte Musiker und ihr Schicksal im „Dritten Reich“ (= Antifaschistische Literatur und Exilliteratur – Studien und Texte, Bd. 25, hg. v. Verein zur Förderung und Erforschung der antifaschistischen Literatur), Wien: Verlag der Theodor Kramer Gesellschaft, 2016 Mozarts Così fan tutte: dramma giocoso und deutsches Singspiel. Frühe Abschriften und frühe Aufführungen, Schliengen: edition argus, 2007 Vom Takt. Untersuchungen zur Theorie und kompositorischen Praxis im ausgehenden 18. und beginnenden 19. Jahrhundert, Wien / Köln / Weimar: Böhlau, 2001 Ernst Krenek – ein Komponist im Exil, Wien: Lafite, 1980 Versuch über die wahre Art, Debussy zu analysieren (= Berliner musikwissenschaftliche Arbeiten 8), München / Salzburg: Katzbichler, 1974 B: Editionen Ernst Krenek. Frühe Lieder für Gesang und Klavier, 3 Hefte, Wien: Universal Edition, 2015 (mit Einleitung, Textteil, Kritischem Bericht) Ernst Krenek - Briefwechsel mit der Universal Edition (1921-1941), 2 Teile, Köln / Weimar / Wien: Böhlau, 2010 „'...la di Ella inaudita finezza'. Zur Entstehung der Varianti. Briefwechsel Luigi Nono – Rudolf Kolisch 1954–1957/58“, in: Schönberg & Nono. A Birthday Offering to Nuria on May 7, 2002, hg. v. Anna Maria Morazzoni, Florenz: Olschki, 2002, S. 267–315 Ernst Krenek: Die amerikanischen Tagebücher 1937–1942. Dokumente aus dem Exil (Hg. u. Übers.), Wien / Köln / Weimar: Böhlau, 1992 Der hoffnungslose Radikalismus der Mitte. Briefwechsel Ernst Krenek – Friedrich T. Gubler 1928–1939 (Hg.), Wien / Köln: Böhlau, 1989 C: Herausgabe Younghi Pagh-Paan. Auf dem Weg zur musikalischen Symbiose, Mainz: Schott, 2020 (wird im Mai/Juni 2020 erscheinen) (zus. mit Gernot Gruber u. Matthias Schmidt:) Ernst Krenek – nicht nur Komponist (= Ernst Krenek Studien 7), Schliengen: edition argus, 2018 Musik, Bühne und Publikum. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

Section 2 Stage Works Operas Ballets Teil 2 Bühnenwerke

SECTION 2 STAGE WORKS OPERAS BALLETS TEIL 2 BÜHNENWERKE BALLETTE 267 268 Bergh d’Albert, Eugen (1864–1932) Amram, David (b. 1930) Mister Wu The Final Ingredient Oper in drei Akten. Text von M. Karlev nach dem gleichnamigen Drama Opera in One Act, adapted from the play by Reginald Rose. Libretto by von Harry M. Vernon und Harald Owen. (Deutsch) Arnold Weinstein. (English) Opera in Three Acts. Text by M. Karlev based on the play of the same 12 Solo Voices—SATB Chorus—2.2.2.2—4.2.3.0—Timp—2Perc—Str / name by Harry M. Vernon and Harald Owen. (German) 57' Voices—3.3(III=Ca).2(II=ClEb).B-cl(Cl).3—4.3.3.1—Timp—Perc— C F Peters Corporation Hp/Cel—Str—Off-stage: 1.0.Ca.0.1—0.0.0.0—Perc(Tamb)—2Gtr—Vc / 150' Twelfth Night Heinrichshofen Opera. Text adapted from Shakespeare’s play by Joseph Papp. (English) _________________________________________________________ 13 Solo Voices—SATB Chorus—1.1.1.1—2.1.1.0—Timp—2Perc—Str C F Peters Corporation [Vocal Score/Klavierauszug EP 6691] Alberga, Eleanor (b. 1949) _________________________________________________________ Roald Dahl’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Text by Roald Dahl (English) Becker, John (1886–1961) Narrator(s)—2(II=Picc).2.2(II=B-cl).1.Cbsn—4.2.2.B-tbn.1—5Perc— A Marriage with Space (Stagework No. 3) Hp—Pf—Str / 37' A Drama in colour, light and sound for solo and mass dramatisation, Peters Edition/Hinrichsen [Score/Partitur EP 7566] solo and dance group and orchestra. -

Christopher Long

Christopher Long ¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶ University Distinguished Teaching Professor School of Architecture 310 Inner Campus Drive, B7500 University of Texas at Austin Austin, TX 78712-1009 tel: (512) 232-4084 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION University of Texas at Austin Ph.D., History, 1993 Dissertation: “Josef Frank and the Crisis of Modern Architecture” M.A., History, 1982 Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 1985–87 Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany, 1980–81 Karl-Franzens-Universität, Institut für südosteuropäische Geschichte, Graz, Austria, 1977–78 University of Texas at San Antonio B.A., Summa cum laude, History, 1978 SELECTED 2016-2017 ACSA Distinguished Professor Award, Association of Collegiate School of FELLOWSHIPS Architecture, 2016 AND AWARDS Book Subvention Award, for The New Space: Movement and Experience in Viennese Architecture, Office of the Vice President for Research, University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Outstanding Scholarship Award, School of Architecture, University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Faculty Research Assignment, University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Fulbright Grant, Vienna, 2014-15 (declined) Kjell och Märta Beijers Stiftelse, Stockholm, publication grant for Josef Frank: Gesammelte Schriften/Complete Writings, 2012 Architectural Research Support Grant, School of Architecture, University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Texas Institute of Letters, Best Scholarly Book Award, 2011 (for The Looshaus) Harwell Hamilton