WP982.Pdf (1.640Mb Application/Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sweden Celebrates 85 Years with Josef Frank

The Frank 85 exhibition is open from September 21th to October 28th, 2018 Sep 21, 2018 13:42 GMT Sweden celebrates 85 years with Josef Frank This year marks 85 years since one of Sweden’s most renowned designers came and enriched his new homeland with colourful prints and timeless interiors. To commemorate this, Svenskt Tenn has created an exhibition presenting a mix of newly produced and classic designs, as well as objects from the archives – all created by Josef Frank. Josef and Anna Frank left their homeland, Austria, in December 1933 due to the rise of anti-Semitism. In January 1934, Josef Frank began a lifelong collaboration with Svenskt Tenn’s founder Estrid Ericson. “With this tribute exhibition we want to show the breadth of Josef Frank’s creativity and how much his designs have contributed to Swedish design history and the present,” says Thommy Bindefeld, marketing manager and creative director. This autumn’s big fabric news is Josef Frank’s Baranquilla, which is now being launched with a black base. There will also be a number of new launches from the archives: Cabinet 2215 is a classic piece of furniture that will return to Svenskt Tenn’s range in 2018, together with a sideboard, a stool a classic captain’s chair and a round dining table. “Estrid Ericson felt that a round dining table with room for eight people was the most suitable for serving dinner, so all of the dinner guests could see and hear each other. Our customers have also been asking for a large, round dining table and subsequently, table 1020 has returned to our range,” says Bindefeld. -

To Mexico in Estrid Ericson's Footsteps – New Exhibition at Svenskt Tenn

Jun 10, 2014 09:30 GMT To Mexico in Estrid Ericson’s footsteps – new exhibition at Svenskt Tenn Svenskt Tenn’s founder Estrid Ericson travelled to Mexico in 1939. She brought 70 boxes of objects back to create an exhibition in the store in Stockholm. Today a new exhibition opens, showing products purchased during a trip in Estrid Ericson’s footsteps in 2013. ’’The world is a book and he who stays at home reads only one page was one of Estrid Ericson’s favorite quotations, which she had engraved on a pewter matchbox. Travel was one of her main sources of inspiration and she was constantly looking for new items for Svenskt Tenn, preferably things that could not be found elsewhere in Sweden’’, says Thommy Bindefeld, Marketing Director at Svenskt Tenn. Ericson’s purchasing journeys took her to many countries and in the spring of 1939 she traveled with her friend Ragnhild Lundberg to Mexico. She looked up producers and placed orders with them directly. A few months later, boatloads of Mexican objects arrived, filling the store on Strandvägen in Stockholm. The show became one of the most appreciated events in the company’s history that far. Today a new exhibition opens, displaying the handpicked items purchased during a trip to Mexico in Estrid Ericson’s footsteps. All items are for sale. ’’It has been very exciting to follow in Estrid Ericson’s footsteps. We have rediscovered some of the items she selected during her trip, and we have also found many other beautiful crafted products that we simply could not resist,’’ says Thommy Bindefeld. -

JOSEF FRANK: Against Design

Press Release JOSEF FRANK: Against Design Press Conference Tuesday, 15 December 2015, 10:30 a.m. Opening Tuesday, 15 December 2015, 7 p.m. Exhibition Venue MAK Exhibition Hall MAK, Stubenring 5, 1010 Vienna Exhibition Dates 16 December 2015 – 12 June 2016 Opening Hours Tue 10 a.m.–10 p.m., Wed–Sun 10 a.m.–6 p.m. Free admission on Tuesdays from 6–10 p.m. “One can use everything that can be used,” proclaimed Josef Frank, one of the most important Austrian architects and designers of modernity, who, with this undogmatic, anti-formalist design approach, was far ahead of his time. More and more, Frank’s architectural sensibility, which placed serviceability and comfort above form and rules of form, counts as trend-setting. The exhibition JOSEF FRANK: Against Design gives a comprehensive overview of the multi-layered oeuvre of this extraordinary architect and designer, while being much more than a survey of his work. This MAK solo exhibition delves into Frank’s complex intellectual and creative strategies, which today are once again highly topical. The exhibition title Against Design encapsulates this undogmatic stance. Frank, who as an architect grappled with all of the themes having to do with architecture and living environments, was also highly productive as a “designer” and developed a plethora of furniture and textiles. Within the international avant-garde, however, he adopted a very critical position. He expressly declared himself opposed to the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, standardized furnishings, and innovative forms for their own sake. He could not really warm up to either the individual-artistic paradigms of the Wiener Werkstätte or to functional, mechanized production deriving from the Bauhaus. -

Estrid Ericson Biography

Estrid Ericson (1884-1981) was a Swedish artist, designer and accomplished entrepreneur responsible for both the establishment and longevity of Svenskt Tenn (Swedish Pewter), a Swedish interior design company for which she served as managing director for 56 years. Together with Nils Fougstedt, Ericson developed Svenskt Tenn into a most influential enterprise involved in manufacturing and design, imports, exports, retail sales and consulting services. Ericson was born in 1894 and raised in Hjo in Vastergotland. In the early 1920s, she trained as a drawing teacher at the Technical School in Stockholm. Thereafter she worked for several years as an art teacher, a pewter artist and interior design consultant at Svenskt Hemslöjd and Willman and Wiklund. In 1924, together with fellow pewter artist Nils Fougstedt, Ericson opened a small pewter workshop, and later in the same year they founded Svenskt Tenn in Stockholm. Initially, Svengst Tenn produced and sold creative modern designs in pewter, which were recognized for their wonderful quality of craftsmanship. In the 1930s, the focus of Svenskt Tenn shifted away from pewter and onto interior design and architect-designed furniture. In 1934, Ericson offered the Austrian architect Josef Frank a position within the firm, which proved to be an important driving collaboration for Svenskt Tenn. Ericson and Frank developed an iconic style that while adopting some of the tenets of functionalism, maintained a warmth, 51 E 10th ST • NEW YORK, NY 10003 phone 212 343 0471 • fax 212 343 0472 51 E 10th ST • NEW YORK, NY 10003 [email protected] • hostlerburrows.com phone 212 343 0471 • fax 212 343 0472 [email protected] • hostlerburrows.com sophistication and elegance particular to the Svenskt Tenn brand. -

International Symposium “Designing Transformation: Jews and Cultural Identity in Central European Modernism”

INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM “DESIGNING TRANSFORMATION: JEWS AND CULTURAL IDENTITY IN CENTRAL EUROPEAN MODERNISM” UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED ARTS VIENNA, MAY 16–17, 2019 INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM “DESIGNING TRANSFORMATION: JEWS AND CULTURAL IDENTITY IN CENTRAL EUROPEAN MODERNISM” UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED ARTS VIENNA, MAY 16–17, 2019 The International Symposium, “Designing Transforma- CONCEPT AND ORGANIZATION: Dr. Elana Shapira tion: Jews and Cultural Identity in Central European DATES: May 16–17, 2019 Modernism,” offers a contemporary scholarly perspec- VENUE: University of Applied Arts Vienna, tive on the role of Jews in shaping and coproducing Vordere Zollamtsstraße 7, 1030 Vienna, Auditorium public and private, as well as commercial and social- COOPERATION PARTNERS: University of Brighton ly-oriented, architecture and design in Central Europe Design Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem from the 1920s to the 1940s, and in the respective coun- and MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / tries in which they settled after their forced emigration Contemporary Art starting in the 1930s. It examines how modern identities evolved in the context of cultural transfers and migra- Organized as part of the FWF (Austrian Science Fund) tions, commercial and professional networks, and in research project “Visionary Vienna: relation to confl icts between nationalist ideologies and Design and Society 1918–1934” international aspirations in Central Europe and beyond. This symposium sheds new light on the importance of integrating Jews into Central European design and aesthetic history by asking symposium participants, including architectural historians and art historians, curators, archivists, and architects, to use their analyses to “design” – in the sense of reconfi gure or reconstruct – the past and push forward a transformation in the historical consciousness of Central Europe. -

Christopher Long

Christopher Long ¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶ University Distinguished Teaching Professor School of Architecture 310 Inner Campus Drive, B7500 University of Texas at Austin Austin, TX 78712-1009 tel: (512) 232-4084 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION University of Texas at Austin Ph.D., History, 1993 Dissertation: “Josef Frank and the Crisis of Modern Architecture” M.A., History, 1982 Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 1985–87 Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany, 1980–81 Karl-Franzens-Universität, Institut für südosteuropäische Geschichte, Graz, Austria, 1977–78 University of Texas at San Antonio B.A., Summa cum laude, History, 1978 SELECTED 2016-2017 ACSA Distinguished Professor Award, Association of Collegiate School of FELLOWSHIPS Architecture, 2016 AND AWARDS Book Subvention Award, for The New Space: Movement and Experience in Viennese Architecture, Office of the Vice President for Research, University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Outstanding Scholarship Award, School of Architecture, University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Faculty Research Assignment, University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Fulbright Grant, Vienna, 2014-15 (declined) Kjell och Märta Beijers Stiftelse, Stockholm, publication grant for Josef Frank: Gesammelte Schriften/Complete Writings, 2012 Architectural Research Support Grant, School of Architecture, University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Texas Institute of Letters, Best Scholarly Book Award, 2011 (for The Looshaus) Harwell Hamilton -

La Seduzione Dell'invisibile

Christina Kruml La seduzione dell’INvisibile Compendio: Josef Frank (1885-1967) La seduzione dell’INvisibile Compendio: Josef Frank (1885-1967) L’architettura “rappresenta una parte importante della nostra vita. Possiamo goderla senza sforzo, la s’incontra per strada e da là essa parla agli uomini come facevano un tempo i filosofi, ed è considerata necessaria da chiunque. Tutti hanno la sensazione di potervi collaborare poiché essa deriva, più di qualsiasi altra arte, da una volontà e da un’attività comuni” (J.Frank, Architettura come simbolo, 1931) UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TRIESTE Sede Amministrativa del Dottorato di Ricerca Scuola di dottorato di ricerca in scienze dell’uomo, della società, del territorio XXII ciclo - a.a. 2009/2010 Settore scientifico disciplinare Icar 14 progettazione architettonica e urbana dottoranda: arch. Christina Kruml responsabile del dottorato di ricerca: prof. Giovanni Fraziano relatore: prof.Giovanni Fraziano Università degli Studi di Trieste © 2011 Christina Kruml, Trieste 10 Introduzione dalla piaga alla piega: considerazioni sull’ABITARE 26 Rannichiarsi negli spazi amati 36 Il gioco e l’ornamento Sommario 52 Parodia del cadavere screziato 64 Ri-vestimento e seduzione 90 L’intonaco bianco come camicia 96 Glossario architessile Compendio: Josef Frank (18 85-1967) c 010 Formazione a Vienna c 024 Berlino c 038 Primi incarichi c 044 Kunstgewerbeschule c 050 Siedlungen o Höfe? c 064 Haus & Garten La seduzione dell’INvisibile. c 072 Werkbund e primi CIAM Note a margine nell’opera di Josef Frank c 092 Stoccolma -

International Symposium “Designing

INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM “DESIGNING TRANSFORMATION: JEWS AND CULTURAL IDENTITY IN CENTRAL EUROPEAN MODERNISM” UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED ARTS VIENNA, MAY 16–17, 2019 INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM “DESIGNING TRANSFORMATION: JEWS AND CULTURAL IDENTITY IN CENTRAL EUROPEAN MODERNISM” UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED ARTS VIENNA, MAY 16–17, 2019 The International Symposium, “Designing Transforma- CONCEPT AND ORGANIZATION: Dr. Elana Shapira tion: Jews and Cultural Identity in Central European DATES: May 16–17, 2019 Modernism,” offers a contemporary scholarly perspec- VENUE: University of Applied Arts Vienna, tive on the role of Jews in shaping and coproducing Vordere Zollamtsstraße 7, 1030 Vienna, Auditorium public and private, as well as commercial and social- COOPERATION PARTNERS: University of Brighton ly-oriented, architecture and design in Central Europe Design Archives, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem from the 1920s to the 1940s, and in the respective coun- and MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / tries in which they settled after their forced emigration Contemporary Art starting in the 1930s. It examines how modern identities evolved in the context of cultural transfers and migra- Organized as part of the FWF (Austrian Science Fund) tions, commercial and professional networks, and in research project “Visionary Vienna: relation to confl icts between nationalist ideologies and Design and Society 1918–1934” international aspirations in Central Europe and beyond. This symposium sheds new light on the importance of integrating Jews into Central European design and aesthetic history by asking symposium participants, including architectural historians and art historians, curators, archivists, and architects, to use their analyses to “design” – in the sense of reconfi gure or reconstruct – the past and push forward a transformation in the historical consciousness of Central Europe. -

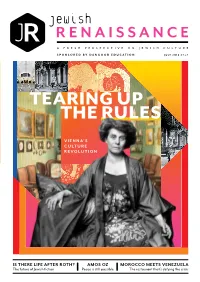

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen. -

Discreet Austerity. Notes on Gabriel Guevrekian's Gardens

Hamed Khosravi Discreet Austerity Notes on Grabriel Guevrekian’s Gardens In spring 1925 Gabriel Guevrekian, a young unknown artist - architect was invited to participate in the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris with a project called Jardin d’Eau et de Lumière. His contribution became one of the most noticed and criticized installations of the exhibition, and by the end, won the Grand Prix by the jurors. The garden was simply a stylized triangular walled space; a piece of landscape captured within a boundary made of concrete and colored glass. At the center of the plot was placed a tiered triangular fountain on top of which an electrically - propelled glass ball — a sculpture made by Louis Baril- let , the French glass artist — was revolving. The space between the fountain and walls was geometrically patterned with triangular patches of flowers and grasses, each of which slightly tilted in a way so that the whole ground plane was traced by folds of green, orange, purple and red (fig. 1). Fig. 1 Jardin d’Eau et de Lumière, by Gabriel Guevrekian 1925. (Excerpted from Michel Roux-Spitz, Bâtiments et jardins. Expo- sition des Arts décoratifs. Paris 1925, p. 74.) Wolkenkuckucksheim | Cloud-Cuckoo-Land | Воздушный замок 20 | 2015 | 34 Khosravi | 199 Contrary to the common European traditions of garden design — French, English, Spanish and Italian styles — Guevrekian’s project put forward a new image of garden, formalized and manifested fully through architec- tural forms, elements and techniques. The garden installation stood against any imitation of nature, both in its form and concept; in a way, the project celebrated architecture as a contrast to nature rather than garden as imi- tation of nature. -

Sid 1 (24) SVEA HOVRÄTT Patent- Och Marknadsöverdomstolen Rotel

Sid 1 (24) SVEA HOVRÄTT DOM Mål nr Patent- och 2020-03-16 PMT 3491-16 marknadsöverdomstolen Stockholm Rotel 020107 ÖVERKLAGAT AVGÖRANDE Stockholms tingsrätts dom 2016-03-22 i mål nr T 14506-13, se bilaga A PARTER Klagande 1. Textilis Ltd 1 Highfield Drive, Fulwood Preston, Lancashire PR2 9SD Storbritannien 2. O.K. Motpart Svenskt Tenn Aktiebolag, 556032-0375 Box 5478 114 84 Stockholm Ombud Jur.kand. B.E. och jur.kand. M.J. Zacco Sweden AB Box 5581 114 85 Stockholm SAKEN Varumärkes- och upphovsrättsintrång ___________________ DOMSLUT Se nästa sida. Dok.Id 1354612 Postadress Besöksadress Telefon Telefax Expeditionstid Box 2290 Birger Jarls Torg 16 08-561 670 00 08-561 675 09 måndag – fredag 103 17 Stockholm 08-561 675 00 09:00–15:00 E-post: [email protected] www.patentochmarknadsoverdomstolen.se Sid 2 SVEA HOVRÄTT DOM PMT 3491-16 Patent- och marknadsöverdomstolen DOMSLUT 1. Patent- och marknadsöverdomstolen avvisar Textilis Ltd:s och O.K.s yrkande om hävning av registreringen av EU-varumärket JOSEF FRANK i figur (nr 011858313). 2. Patent- och marknadsöverdomstolen fastställer punkterna 2, 3, 6–8 i tingsrättens domslut och ändrar tingsrättens domslut på så sätt att förbudet i punkten 4 ska ha följande lydelse. Envar av Textilis Ltd och O.K. förbjuds a) att, vid vite om 200 000 kr för varje trettiodagarsperiod under vilken förbudet inte har följts, i Sverige bjuda ut till försäljning eller på annat sätt till allmän- heten sprida alster som framgår av bilaga 3 till tingsrättens dom, b) att, vid vite om 200 000 kr för varje trettiodagarsperiod under vilken förbudet inte har följts, i Sverige använda kännetecknet JOSEF FRANK (nr 000227355) för tyger, kuddar och möbler och c) att, vid vite om 200 000 kr för varje trettiodagarsperiod under vilken förbudet inte har följts, i Sverige använda kännetecknet MANHATTAN (nr 010540268) för tyger, kuddar och möbler. -

Estrid Ericson's Classic Elephant Design Now Available As Wallpaper

Apr 03, 2013 10:01 GMT Estrid Ericson’s classic elephant design now available as wallpaper One of the most beloved Svenskt Tenn textile prints – ‘’Elefant’’ by Estrid Ericson – is now available as wallpaper in three different colour combinations with white elephants on a base of midnight blue, elephant grey or raspberry. Estrid Ericson, founder of Svenskt Tenn, often found her ideas while travelling around the world. It was in a market in the south of France that she found a piece of batik fabric from the Belgian Congo, and was inspired to create the now well-known elephant print. It was printed on textile in the late 1930s. Now for the first time it is available on wallpaper. All of Svenskt Tenn’s wallpapers are made in Sweden on non-chlorine bleached paper using water-based colours. The wallpapers are washable and withstand well to exposure to sunlight. Prices: SEK 750 per roll. Each roll gives four print matched lengths 2.5 meters high. The Elefant wallpaper is available from April 5th. In addition, the exhibition Primavera, Textile inspiration-Inspiring textile, will be shown in the store on Strandvägen in Stockholm from April 5th until May 19th. Svenskt Tenn was founded in 1924 by designer and drawing teacher Estrid Ericson (1894-1981). In 1934, she began her lifelong collaboration with Josef Frank, already an internationally well-known architect, urban planner and designer, who had recently left Austria to take up residence in Sweden. Together, the two laid the foundations for the interior design philosophy that Svenskt Tenn has since come to represent, combining Estrid Ericson's artistic talent and entrepreneurial spirit with Josef Frank's inspired and timeless designs to form what was soon to become a highly successful concept.