Making Operas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

A Study of Ravel's Le Tombeau De Couperin

SYNTHESIS OF TRADITION AND INNOVATION: A STUDY OF RAVEL’S LE TOMBEAU DE COUPERIN BY CHIH-YI CHEN Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University MAY, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music ______________________________________________ Luba-Edlina Dubinsky, Research Director and Chair ____________________________________________ Jean-Louis Haguenauer ____________________________________________ Karen Shaw ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my tremendous gratitude to several individuals without whose support I would not have been able to complete this essay and conclude my long pursuit of the Doctor of Music degree. Firstly, I would like to thank my committee chair, Professor Luba Edlina-Dubinsky, for her musical inspirations, artistry, and devotion in teaching. Her passion for music and her belief in me are what motivated me to begin this journey. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor Jean-Louis Haguenauer and Dr. Karen Shaw, for their continuous supervision and never-ending encouragement that helped me along the way. I also would like to thank Professor Evelyne Brancart, who was on my committee in the earlier part of my study, for her unceasing support and wisdom. I have learned so much from each one of you. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Mimi Zweig and the entire Indiana University String Academy, for their unconditional friendship and love. They have become my family and home away from home, and without them I would not have been where I am today. -

(MTO 21.1: Stankis, Ravel's ficolor

Volume 21, Number 1, March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Society for Music Theory Maurice Ravel’s “Color Counterpoint” through the Perspective of Japonisme * Jessica E. Stankis NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.15.21.1/mto.15.21.1.stankis.php KEYWORDS: Ravel, texture, color, counterpoint, Japonisme, style japonais, ornament, miniaturism, primary nature, secondary nature ABSTRACT: This article establishes a link between Ravel’s musical textures and the phenomenon of Japonisme. Since the pairing of Ravel and Japonisme is far from obvious, I develop a series of analytical tools that conceptualize an aesthetic orientation called “color counterpoint,” inspired by Ravel’s fascination with Chinese and Japanese art and calligraphy. These tools are then applied to selected textures in Ravel’s “Habanera,” and “Le grillon” (from Histoires naturelles ), and are related to the opening measures of Jeux d’eau and the Sonata for Violin and Cello . Visual and literary Japonisme in France serve as a graphical and historical foundation to illuminate how Ravel’s color counterpoint may have been shaped by East Asian visual imagery. Received August 2014 1. Introduction It’s been given to [Ravel] to bring color back into French music. At first he was taken for an impressionist. For a while he encountered opposition. Not a lot, and not for long. And once he got started, what production! —Léon-Paul Fargue, 1920s (quoted in Beucler 1954 , 53) Don’t you think that it slightly resembles the gardens of Versailles, as well as a Japanese garden? —Ravel describing his Le Belvédère, 1931 (quoted in Orenstein 1990 , 475) In “Japanizing” his garden, Ravel made unusual choices, like his harmonies. -

Modern French Composers: I. How They Are Encouraged Author(S): M

Modern French Composers: I. How They Are Encouraged Author(s): M. D. Calvocoressi Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 62, No. 938 (Apr. 1, 1921), pp. 238-240 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/909393 Accessed: 04-11-2015 08:30 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.237.29.138 on Wed, 04 Nov 2015 08:30:43 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 238 THE MUSICAL TIMES-APRIL I 1921I Ex. 5. I , opinion of posterity,it is not unlikelythat most of us would be overwhelmed with surprise- - - as most of Kiss me and take my sol in exactly Beethoven's contemporaries . would have been had theyknown what his ultimate standingwould be. Even withoutattempting to deliverjudgment as to the comparativemerits of the modern French school, there is one statementthat can unhesi- tatinglybe made: of all countries that have constantlytaken an interestin music, none has rit. hoco oPP duringthe past hundred yearsor so made greater headway than France. -

Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27Th, 2021 at 3:30Pm

Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27th, 2021 at 3:30pm Roma Folk Dances: Villages Tunes of the Hungarian Roma. Daniel Sender (1982-) I. Ha elvettél, tartsá (Öcsöd) II. I canka uj Anna (Püspökladány) III. Hallgató (Mezókovácsháza) for Violin Solo IV. Ének (Püspökladány) V. Jaj, anyám, a vakaró (Csenyéte) Daniel Sender is currently the concertmaster of the Charlottesville Symphony and the Charlottesville Opera, as well as associate violin professor at UVA. Sender studied at Ithaca College, the University of Maryland–where he received his PhD, the Liszt Academy (Budapest) and the Institute for European Studies (Vienna). His scholarship in Hungarian music began when he was awarded a Fulbright Student Scholar grant for his research in Budapest (2010-11), where he attended the Liszt Academy as a student of Vilmos Szabadi and became interested in Hungarian Roma folk music. (Note: unless otherwise stated, assume “Hungary” in terms of folk music geographically refers to the late Austro-Hungarian Empire which existed prior to the Treaty of Trianon. At the end of WWI, the Treaty of Trianon split 75% of Austro-Hungary’s territory up into modern day Romania, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and the Balkans.) The Roma people in Hungary–also known as Romani people, and previously, “gypsies,” though that term is now considered outdated slang, are the largest minority group in Hungary, making up between 3 and 7% of the population. There is a clear cultural divide between those who consider themselves native Hungarians, and Roma people. A large proportion of the Roma population lives in extreme poverty and faces constant racial discrimination, while the European Union and Hungarian officials are only just beginning to take accountability. -

Baur 831792.Pdf (5.768Mb)

Ravel's "Russian" Period: Octatonicism in His Early Works, 1893-1908 Author(s): Steven Baur Source: Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Autumn, 1999), pp. 531-592 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/831792 Accessed: 05-05-2016 18:10 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press, American Musicological Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Musicological Society This content downloaded from 129.173.74.49 on Thu, 05 May 2016 18:10:01 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Ravel's "Russian" Period: Octatonicism in His Early Works, 1893-1908 STEVEN BAUR The most significant writing on the octatonic scale in Western music has taken as a starting point the music of Igor Stravinsky. Arthur Berger introduced the term octatonic in his landmark 1963 article in which he identified the scale as a useful framework for analyzing much of Stravinsky's music. Following Berger, Pieter van den Toorn discussed in greater depth the nature of Stravinsky's octatonic practice, describing the composer's manipula- tions of the harmonic and melodic resources provided by the scale. -

May, 1952 TABLE of CONTENTS

111 AJ( 1 ~ toa TlE PIANO STYI2 OF AAURICE RAVEL THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Jack Lundy Roberts, B. I, Fort Worth, Texas May, 1952 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OFLLUSTRTIONS. Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF PIANO STYLE ... II. RAVEL'S MUSICAL STYLE .. # . , 7 Melody Harmony Rhythm III INFLUENCES ON RAVEL'S EIANO WORKS . 67 APPENDIX . .* . *. * .83 BTBLIO'RAWp . * *.. * . *85 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Jeux d'Eau, mm. 1-3 . .0 15 2. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), mm. la-3 .r . -* - -* . 16 3. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), 3 a. « . a. 17 4. Ondine (Gaspard de a Nuit), m. 1 . .... 18 5. Ondine (Gaspard de la Nuit), m. 90 . 19 6. Sonatine, first movement, nm. 1-3 . 21 7. Sonatine, second movement, 22: 8. Sonatine, third movement, m m . 3 7 -3 8 . ,- . 23 9. Sainte, umi. 23-25 . * * . .. 25 10. Concerto in G, second movement, 25 11. _Asi~e (Shehdrazade ), mm. 6-7 ... 26 12. Menuet (Le Tombeau de Coupe rin), 27 13. Asie (Sh6hlrazade), mm. 18-22 . .. 28 14. Alborada del Gracioso (Miroirs), mm. 43%. * . 8 28 15. Concerto for the Left Hand, mii 2T-b3 . *. 7-. * * * .* . ., . 29 16. Nahandove (Chansons Madecasses), 1.Snat ,-5 . * . .o .t * * * . 30 17. Sonat ine, first movement, mm. 1-3 . 31 iv Figure Page 18. Laideronnette, Imperatrice des l~~e),i.......... Pagodtes (jMa TV . 31 19. Saint, mm. 4-6 « . , . ,. 32 20. Ondine (caspard de la Nuit), in. 67 .. .4 33 21. -

Resource Pack: Ravel

RESOURCE PACK: RAVEL musicbehindthelines.org FOOTER INSERT ACE LOGO RPO LOGO WML LOGO MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937) RAVEL: FURTHER REFERENCE ABOUT BEHIND THE LINES Books, Scores & Audio BIOGRAPHY Periodicals Ravel during the War Websites Chronology of Key dates WW1 CENTENARY LINKS FEATURED COMPOSITIONS Le tombeau de Couperin La Valse Page | 2a About Behind the Lines Behind the Lines was a year-long programme of free participatory events and resources for all ages to commemorate the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. The programme was delivered in partnership by Westminster Music Library and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and supported using public funding by Arts Council England. Public Workshops Beginning in autumn 2013, educational leaders and world-class musicians from the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra led a series of 18 interactive workshops for adults and families (early years and primary age focus). Sessions explored the music and composers of the First World War through these engaging creative composition workshops, targeted at the age group specified, and using the music and resources housed in Westminster Music Library. Schools Projects In addition to the public workshop series, Behind the Lines also worked with six schools in Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea; two secondaries and four primaries. These six schools participated in 2 day creative composition projects which drew upon the themes of the programme and linked in with the schools own learning programmes – in particular the History, Music and English curriculum. Additional schools projects can be incorporated in to the Behind the Lines programme between 2014 – 2018, although fundraising will be required. -

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

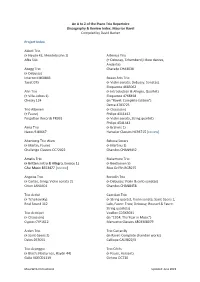

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms -

The Piano Trio, the Duo Sonata, and the Sonatine As Seen by Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Ravel

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: REVISITING OLD FORMS: THE PIANO TRIO, THE DUO SONATA, AND THE SONATINE AS SEEN BY BRAHMS, TCHAIKOVSKY, AND RAVEL Hsiang-Ling Hsiao, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Professor Rita Sloan School of Music This performance dissertation explored three significant piano trios, two major instrumental sonatas and a solo piano sonatine over the course of three recitals. Each recital featured the work of either Brahms, Tchaikovsky or Ravel. Each of these three composers had a special reverence for older musical forms and genres. The piano trio originated from various forms of trio ensemble in the Baroque period, which consisted of a dominating keyboard part, an accompanying violin, and an optional cello. By the time Brahms and Tchaikovsky wrote their landmark trios, the form had taken on symphonic effects and proportions. The Ravel Trio, another high point of the genre, written in the early twentieth century, went even further exploring new ways of using all possibilities of each instrument and combining them. The duo repertoire has come equally far: duos featuring a string instrument with piano grew from a humble Baroque form into a multifaceted, flexible classical form. Starting with Bach and continuing with Mozart and Beethoven, the form traveled into the Romantic era and beyond, taking on many new guises and personalities. In Brahms’ two cello sonatas, even though the cello was treated as a soloist, the piano still maintained its traditional prominence. In Ravel’s jazz-influenced violin sonata, he treated the two instruments with equal importance, but worked with their different natures and created an innovative sound combination. -

A Sociology of the Apaches: 'Sacred Battalion' for Pelléas

CHAPTER NINE A Sociology of the Apaches: ‘Sacred Battalion’ for Pelléas JANN PASLER 28 April 1902 It was like any other day. One left one’s apartment, one’s head still buzzing with the nothingness of daily affairs, saddened by female betrayals (who cares?), crushed by wounds of friendship (so cruel). Crossing the swarming boulevard, one entered a theatre full of the babbling gossips who attend afternoon dress rehearsals. High- necked dresses, drab jackets, pince-nez and bald heads always seemed the same. Someone was selling programs with a plot summary of the new opera we’d all come to see, Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. But people reading it were laughing, some calling it Pédéraste et Médisante [Pederast and Slanderer]. Why, I asked myself? The only performance of Maeterlinck’s play almost ten years ago by the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre was practically a dramatic rite. Maeterlinckophilia has become a religion and more intolerant than any other cult has ever been … Critics told us in advance that we were not capable of understanding Maeterlinck’s genius and, if we wouldn’t admire without understanding, we were simple idiots. Well! I think I understood Pelléas quite well! But now Maeterlinck is acting like a perfect fool. Only two weeks ago he wrote to Le Figaro disassociating himself from the work because Debussy made ‘arbitrary and absurd cuts that rendered the work incomprehensible.’ We know he was upset because the composer refused to cast his full-voiced girlfriend as Mélisande. All this even though he gave Debussy carte blanche with the work 10 years ago. -

Introduction

Introduction Two months after the premiere of Maurice Ravel’s Histoires naturelles in 1908, Claude Debussy wrote to the music critic Louis Laloy, describing his fellow com- poser with a pair of unusual terms: “I agree with you in acknowledging that Ravel is exceptionally gifted, but what irritates me is his posture as a ‘faiseur de tours,’ or better yet, as an enchanting fakir, who can make flowers spring up around a chair. Unfortunately, a trick is always prepared, and it can only astonish once!”1 Neither “faiseur de tours” (performer of tricks) nor “fakir” was in common usage in the early twentieth century, though the latter term would have been known from Judith Gautier’s historical novel La Conquête du paradis (1890), whose title aptly captures its romanticized, colonialist perspective on eighteenth-century India. By linking him to conjurers—whether theatrical entertainers or exoticized thauma- turgists—Debussy impugned the long-term prospects of Ravel’s work. How could a trick with a looming expiration date produce music that would withstand repeat performances without unveiling its mysteries or losing its luster? Ravel’s music, for all its silvery charm, would soon tarnish; the weight of passing time would grind it to dust. To hear it once was to exhaust its secrets. But Debussy’s criticism was rapidly turned on its head by critics, biographers, and scholars who found in the language of conjuring the words they needed to combat Ravel’s detractors. Laloy, for one, compared Ravel to a sorcerer in a 1909 review of Gaspard de la nuit and described him as a “magician of sounds” when 1.