Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 79, 1959-1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

Italian Itineraries

r n a i t l i o u i 2 2 2 G V 2 2 2 - - i i / / / l d l r 1 1 e 1 a i r n 2 2 O 2 r b e a 0 0 0 B G o 2 2 2 o z i r n e e r v S S S o a S L T T T U C C C E E E J J J O O O R R R D P P P DUO SAVERIO GABRIELLI (VIOLIN) - LORENZO BERNARDI (GUITAR) - PROJECTS 2021/2022 - TWO ITALIANS IN VIENNA - THE ITINERARIES OF ITALIAN VIRTUOSITIES D O S S I E R - G A B R I E L L I B E R N A R D I D U O Projects 2021 - 2022 TWO ITALIANS IN VIENNA Proposal 1 THE ITINERARIES OF ITALIAN VIRTUOSITIES Proposal 2 Hence the idea of the "Two Italians in Vienna" t w o project, which summarizes precisely that trend, of ITALIANS which Paganini and Giuliani are witnesses, which has seen many Italian musicians emigrate to the main i n VIENNA European capitals, including Vienna, where instrumental music was mostly enhanced. To intensify the link with Vienna, it is interesting to Vienna has been a very important hub for the investigate the role of Anton Diabelli, Austrian two most important personalities of the violin composer, pianist, and publisher, to whom and guitar: Niccolò Paganini and Mauro Beethoven himself looked with admiration (famous Giuliani. At the beginning of the nineteenth the so-called “Diabelli” Variations op. -

Rawson Duo Concert Series, 2014-15 Magyar Fantázia

What’s Next? November: Magyar Fantazia Pt. 2 – Bartok, a Microcosmos ~ On Friday and Sunday, Rawson Duo Concert Series, 2014-15 November 14 & 16, 2 pm the Rawson Duo will present the second of their Hungarian landscapes, moving beyond the streets of Budapest with its looming figure of Franz Liszt to take in Bartok’s awakening of an eastern identity in a sampling of his rural, folk-inspired miniatures along with Romanian Rhapsody No. 2 and one of his greatest chamber music masterpieces, the 1921 Sonata for violin and piano – powerfully brilliant in its color and effect, at times extroverted, intimate, and sensual to the extreme, one of their absolute favorite duos to play which has been kept under wraps for some time. December: Nordlys, music of Scandinavian composers ~ On Friday and Sunday, December 19 and 21, 2 pm the Rawson Duo will present their eighth annual Nordlys (Northern Lights) concert showcasing works by Scandinavian composers. Grieg, anyone? s e a s o n p r e m i e r e Beyond that? . as the fancy strikes (check those emails and website) Magyar Fantázia Reservations: Seating is limited and arranged through advanced paid reservation, $25 (unless otherwise noted). Contact Alan or Sandy Rawson, email [email protected] or call 379- 3449. Notice of event details, dates and times when scheduled will be sent via email or ground mail upon request. Be sure to be on the Rawsons’ mailing list. For more information, visit: www.rawsonduo.com H A N G I N G O U T A T T H E R A W S O N S (take a look around) Harold Nelson has had a lifelong passion for art, particularly photo images and collage. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 94, 1974-1975

THE FRIENDS OF THE COLLEGE Presents BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA, Music Director COLIN DAVIS, Principal Guest Conductor Ninty-fourth Season Monday evening, November 18, 1974 Tuesday evening, November 19, 1974 SEIJI OZAWA, Conductor William Neal Reynolds Coliseum 8 P.M. PROGRAM Le tombeau de Couperin Maurice Ravel Prelude Forlane Menuet Rigaudon Ostensibly this music represents neoclassic expression in its purest distillate. And it was, indeed, conceived as a pianistic idealization of the clavecin aesthetic exemplified by Francois Couperin le Crand. But that was in the fateful summer of 1914, and even Ravel's sleepy St. Jean-de-Luz was traumatized by the news of Archduke Francis Ferdinand's assassination at Sarajevo. France mobilized overnight, and by August was at war. By then the sketches for Le tombeau de Couperin were in a desk drawer. When he returned to them three wretched years later the composer was a very different man, broken in health and shattered emotionally by the loss of his mother, who had died barely a week after his medical discharge. Thus it was that the six movements became as many 'tomb- stones' (each one inscribed separately) for friends and regimental comrads who had been killed on the Western Front. As a work for solo piano—Ravel's last, incidentally—Le tombeau was not a notable success. Strictly speaking it could not have been because it marked a stylistic retrogression after the harmonic leaps forward in the Valse nobles et sentimentales and Gas-pard de la nuit. But fortu- nately that was not the end of the matter. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra

ABRAHAM cf ..."' c ="' HOODS UP TO THE AMERICAN WAY WITH WOOL Blanket plaid ... toggle terrific, either way you coat it this fall ... A&S says do it with pure wool fabric made in America! PURE WOOL® "The Wool mark is your assurance of a quality tested product made of pure wool" -----------------------------------OCTOBER, 1971 I BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC I 3 Thursday Evening, October 28, 1971 , 8:30 p.m. Subscription Performance The Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences presents the Boston Symphony Orchestra \X:'illiam Steinberg, Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas, Associate Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, Conducting Polonaise and Krakoviak from 'A Life for the Tsar' MIKHAIL GLINKA Symphony in C IGOR STRAVINSKY Mode.rato alia breve Larghetto concertante Allegretto Largo - tempo giu sto, alia breve IN TERMISSION Concerto for flute, oboe, piano and percussion EDISON DENISOV Overture: allegro moderato Cadenza: Iento rubato - allegro Coda: allegro giusto DORIOT ANTHONY DWYER, flute RALPH GOMBERG, oboe GILBERT KALISH, piano EVERETT FIRTH, percussion Symphony No. 2 in B minor, Op. 5 ALEXANDER BORODIN Allegro Scherzo: prestissimo - allegretto Andante Finale: allegro The Boston Symphony Orchestra records exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon. BALDWIN PIANO DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON AND RCA RECORDS 4 I BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC I OCTOBER, 1971 The Brooklyn Academy of Mus 1 c The t. Felix Street Corporation Administrative Staff Board of Directors : Harvey Lichtenstein, Director Seth S. Faison, Chairman Lewis L. Lloyd, General Manager Donald M. Blinken, President John V. Lindsay, Honorary Chairman Charles Hammock, Asst. General Manager M arti·n P. Carter Jane Yackel, Comptroller Barbaralce Diamonstein Thomas Kerrigan, Assistant to the Director Mrs. -

Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27Th, 2021 at 3:30Pm

Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27th, 2021 at 3:30pm Roma Folk Dances: Villages Tunes of the Hungarian Roma. Daniel Sender (1982-) I. Ha elvettél, tartsá (Öcsöd) II. I canka uj Anna (Püspökladány) III. Hallgató (Mezókovácsháza) for Violin Solo IV. Ének (Püspökladány) V. Jaj, anyám, a vakaró (Csenyéte) Daniel Sender is currently the concertmaster of the Charlottesville Symphony and the Charlottesville Opera, as well as associate violin professor at UVA. Sender studied at Ithaca College, the University of Maryland–where he received his PhD, the Liszt Academy (Budapest) and the Institute for European Studies (Vienna). His scholarship in Hungarian music began when he was awarded a Fulbright Student Scholar grant for his research in Budapest (2010-11), where he attended the Liszt Academy as a student of Vilmos Szabadi and became interested in Hungarian Roma folk music. (Note: unless otherwise stated, assume “Hungary” in terms of folk music geographically refers to the late Austro-Hungarian Empire which existed prior to the Treaty of Trianon. At the end of WWI, the Treaty of Trianon split 75% of Austro-Hungary’s territory up into modern day Romania, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and the Balkans.) The Roma people in Hungary–also known as Romani people, and previously, “gypsies,” though that term is now considered outdated slang, are the largest minority group in Hungary, making up between 3 and 7% of the population. There is a clear cultural divide between those who consider themselves native Hungarians, and Roma people. A large proportion of the Roma population lives in extreme poverty and faces constant racial discrimination, while the European Union and Hungarian officials are only just beginning to take accountability. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 83,1963-1964, Trip

BOSTON • r . SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY /'I HENRY LEE HIGGINSON TUESDAY EVENING 4 ' % mm !l SERIES 5*a ?^°£D* '^<\ -#": <3< .4) \S? EIGHTY-THIRD SEASON 1963-1964 TAKE NOTE The precursor of the oboe goes back to antiquity — it was found in Sumeria (2800 bc) and was the Jewish halil, the Greek aulos, and the Roman tibia • After the renaissance, instruments of this type were found in complete families ranging from the soprano to the bass. The higher or smaller instruments were named by the French "haulx-bois" or "hault- bois" which was transcribed by the Italians into oboe which name is now used in English, German and Italian to distinguish the smallest instrument • In a symphony orchestra, it usually gives the pitch to the other instruments • Is it time for you to take note of your insurance needs? • We welcome the opportunity to analyze your present program and offer our professional service to provide you with intelligent, complete protection. invite i . We respectfully* your inquiry , , .,, / Associated with CHARLES H. WATKINS CO. & /qbrioN, RUSSELL 8c CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton / 147 milk street boston 9, Massachusetts/ Insurance of Every Description 542-1250 EIGHTY-THIRD SEASON, 1963-1964 CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra ERICH LEINSDORF, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Talcott M. Banks Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Abram Berkowitz Henry A. Laughlin Theodore P. Ferris John T. Noonan Francis W. Hatch Mrs. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 93, 1973-1974

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 THURSDAY A6 FRIDAY-SATURDAY 22 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President PHILIP K. ALLEN SIDNEY STONEMAN JOHN L. THORNDIKE Vice-President Vice-President Treasurer VERNON R. ALDEN MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK JOHN T. NOONAN ALLEN G. BARRY HAROLD D. HODGKINSON MRS JAMES H. PERKINS MRS JOHN M. BRADLEY E. MORTON JENNINGS JR IRVING W. RABB RICHARD P. CHAPMAN EDWARD M. KENNEDY PAUL C. REARDON ABRAM T. COLLIER EDWARD G. MURRAY MRS GEORGE LEE SARGENT ARCHIE C EPPS III JOHN HOYT STOOKEY TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. CABOT HENRY A. LAUGHLIN PALFREY PERKINS FRANCIS W. HATCH EDWARD A. TAFT ADMINISTRATION OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THOMAS D. PERRY JR THOMAS W. MORRIS Executive Director Manager PAUL BRONSTEIN JOHN H. CURTIS MARY H. SMITH Business Manager Public Relations Director Assistant to the Manager FORRESTER C. SMITH DANIEL R. GUSTIN RICHARD C. WHITE Development Director Administrator of Assistant to Educational Affairs the Manager DONALD W. MACKENZIE JAMES F. KILEY Operations Manager, Operations Manager, Symphony Hall Tanglewood HARRY NEVILLE Program Editor Copyright © 1974 by Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS ^H jgfism SPRING LINES" Outline your approach to spring. In greater detail with our hand- somely tailored, single breasted, navy wool worsted coat. Subtly smart with yoked de- tail at front and back. Elegantly fluid with back panel. A refined spring line worth wearing. $150. Coats. Boston Chestnut Hill Northshore Shopping Center South Shore PlazaBurlington Mall Wellesley BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 THE BOARD OF OVERSEERS OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. -

Bruno Walter (Ca

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky Yale University Press New Haven and London Frontispiece: Bruno Walter (ca. ). Courtesy of Österreichisches Theatermuseum. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Grand Rapids, Mich. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley,Harrisonburg, Va. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ryding, Erik S., – Bruno Walter : a world elsewhere / by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references, filmography,and indexes. ISBN --- (cloth : alk. paper) . Walter, Bruno, ‒. Conductors (Music)— Biography. I. Pechefsky,Rebecca. II. Title. ML.W R .Ј—dc [B] - A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. For Emily, Mary, and William In memoriam Rachel Kemper and Howard Pechefsky Contents Illustrations follow pages and Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Bruno Schlesinger Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg,– Kapellmeister Walter Breslau, Pressburg, Riga, Berlin,‒ -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 108, 1988-1989

9fi Natl ess *£ IH f iMMHHl BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS Sunday, February 5, 1989, at 3:00 p.m. at Jordan Hall BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS Malcolm Lowe, violin Harold Wright, clarinet i j Burton Fine, viola Sherman Walt, bassoon Jules Eskin, cello Charles Kavalovski, horn M Edwin Barker, double bass Charles Schlueter, trumpet SH gK£*!S Doriot Anthony Dwyer, flute Ronald Barron, trombone m Wm Alfred Genovese, oboe Everett Firth, percussion with guest artists GILBERT KALISH, piano LAWRENCE ISAACSON, trombone clarinet PRESS, percussion PETER HADCOCK, ARTHUR ^flilHH lH mi* '^.v.' RICHARD PLASTER, bassoon FRANK EPSTEIN, percussion Ml . TIMOTHY MORRISON, trumpet ROSEN, celesta JEROME JH H Hi BSS LEON KIRCHNER, conductor Hi PISTON Quintet for Wind Instruments aflMnCc HH H #Bt«3P'j Hi HI Animato Con tenerezza Scherzando Allegro comodo Ms. DWYER, Mr. GENOVESE, Mr. HADCOCK, Mr. WALT, and Mr. KAVALOVSKI KIRCHNER Concerto for Violin, Cello, Ten Winds, and Percussion (in two movements) Messrs. LOWE and ESKIN; Ms. DWYER; Messrs. GENOVESE, HADCOCK, WALT, PLASTER, KAVALOVSKI, SCHLUETER, MORRISON, BARRON, ISAACSON, FIRTH, PRESS, EPSTEIN, and ROSEN LEON KIRCHNER, conductor HI Hi^HB OTH INTERMISSION HHHH FAURE Quartet No. 1 in C minor for piano and strings, Opus 15 WtmHHSSm Allegro molto moderato Scherzo: Allegro vivo Adagio Allegro molto I Messrs. KALISH, LOWE, FINE, and ESKIN -BHHHflntflElflfli • <&& Baldwin piano Nonesuch, DG, RCA, and New World records tSHHIS WHliHill The Boston Symphony Orchestra gratefully acknowledges the support of the National Endow- &<- ment for the Arts, and of the Massachusetts Council on the Arts and Humanities, a state agency. Walter Piston Quintet for Wind Instruments Early in his career, Walter Piston began a woodwind quintet that he left unfinished in frustration at the inherent technical problems of the medium—the recalcitrant indi- viduality of the five voices, with their different techniques and their very different sonorities, which could never quite be made to blend. -

Ronald Roseman: a Biographical Description and Study of His Teaching Methodology

LAMPIDIS, ANNA, D.M.A. Ronald Roseman: A Biographical Description and Study of his Teaching Methodology. (2008) Directed by Dr. Mary Ashley Barret. 103 pp. Ronald Roseman was an internationally acclaimed oboe soloist, chamber musician, teacher, recording artist, and composer whose career spanned over 40 years. A renowned oboist, he performed in some of America’s most influential institutions and ensembles including the New York Woodwind Quintet, the New York Philharmonic, and the New York Bach Aria Group. His contributions to 20th Century oboe pedagogy through his own unique teaching methodology enabled him to contribute to the success of both his own personal students and many others in the field of oboe and woodwind performance. His body of compositions that include oboe as well as other instruments and voice serve to encapsulate his career as a noteworthy 20th Century composer. Roseman’s musicianship and unique teaching style continues to be admired and respected worldwide by oboists and musicians. The purpose of this study is to present a biographical overview and pedagogical techniques of oboist Ronald Roseman. This study will be divided into sections about his early life, teaching career, performance career and his pedagogical influence upon his students. Exercises and techniques developed by Roseman for the enhancement of oboe pedagogy will also be included. Interviews have been conducted with his wife and three former well-known students in order to better serve the focus of this study. The author also contributed pedagogical techniques compiled during a two-year period of study with Roseman. Appendices include a discography of recorded materials, the New York Woodwind Quintet works list, Roseman’s published article on Baroque Ornamentation, a list of his compositions with premiere dates and performers, and interview questions. -

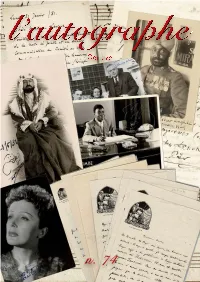

Genève L’Autographe

l’autographe Genève l’autographe L’autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201 Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in EURO and do not include postage. All overseas shipments will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefts of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, Paypal and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfnance CCP 61-374302-1 3, rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: CH 94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped via Federal Express on request. Music and theatre p. 4 Miscellaneous p. 38 Signed Pennants p. 98 Music and theatre 1. Julia Bartet (Paris, 1854 - Parigi, 1941) Comédie-Française Autograph letter signed, dated 11 Avril 1901 by the French actress. Bartet comments on a book a gentleman sent her: “...la lecture que je viens de faire ne me laisse qu’un regret, c’est que nous ne possédions pas, pour le Grand Siècle, quelque Traité pareil au vôtre. Nous saurions ainsi comment les gens de goût “les honnêtes gens” prononçaient au juste, la belle langue qu’ils ont créée...”. 2 pp. In fine condition. € 70 2. Philippe Chaperon (Paris, 1823 - Lagny-sur-Marne, 1906) Paris Opera Autograph letter signed, dated Chambéry, le 26 Décembre 1864 by the French scenic designer at the Paris Opera.