Ronald Roseman: a Biographical Description and Study of His Teaching Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

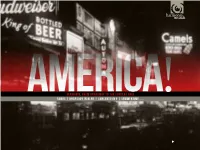

Gershwin, from Broadway to the Concert Hall SONGS

Gershwin, from Broadway to the Concert Hall americaSONGS | RHAPSODY IN BLUE | CONCERTO IN F | SUMMERTIME . ! Volume 1 Volume 2 GEORGE GERSHWIN (1898-1937) ORCHESTRAL MUSIC PIANO SOLO 1 “I Got Rhythm” Variations for Piano and Orchestra (1934) 8’29 Original orchestration by George Gershwin Song Book (18 hit songs arranged by the composer) 2 4’05 1 The Man I Love. Slow and in singing style 2’25 Summertime George Gershwin, DuBose Heyward. From Porgy and Bess, 1935 2 I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise. Vigorously 0’44 3 ‘s Wonderful. Liltingly 1’00 3 Rhapsody in Blue (1924) 15’31 4 I Got Rhythm. Very marked 1’05 Original ‘jazz band’ version 5 Do It Again. Plaintively 1’38 © Warner Bros. Music Corporation 6 Clap Yo’Hands. Spirited (but sustained) 0’56 Lincoln Mayorga, piano (1-3) 7 Oh, Lady Be Good. Rather slow (with humour) 1’04 8 Fascinating Rhythm. With agitation 0’51 Harmonie Ensemble / New York, Steven Richman 9 Somebody Loves Me. In a moderate tempo 1’17 10 My One and Only. Lively (in strong rhythm) 0’51 11 That Certain Feeling. Ardently 1’36 Piano Concerto in F 12 Swanee. Spirited 0’38 4 I. Allegro 13’18 13 Sweet and Low Down. Slow (in a jazzy manner) 1’05 5 II. Adagio 12’32 14 Nobody But You. Capriciously 0’53 6 III. Allegro agitato 6’48 15 Strike Up the Band. In spirited march tempo 0’56 7 Cuban Overture 10’36 16 Who Cares? Rather slow 1’30 © WB Music Corp. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

INSTRUMENT REGISTRATION PACKET (Band and Orchestra)

Reading Fleming Intermediate School 20162017 INSTRUMENT REGISTRATION PACKET (Band and Orchestra) For Students and Parents Ms. Susan Guckin Mrs. Audrey Spies [email protected] [email protected] Welcome to RFIS and the opportunity to learn to play a musical instrument! This packet outlines the responsibilities and policies of the instrumental music program to insure a successful year. Today your child observed an instrument demonstration to help them decide if and which instrument they would like to learn. Please take some time to discuss this opportunity with your child and the responsibilities that come along with it. Band and Orchestra is offered to all 5th and 6th grade students during the school day. Lessons take place during their TWC period. Students are not taken out of academics. If you decide to study an instrument, complete and return the last page of this packet to register your child for the program by TUESDAY, 9/13. Note that students are not required to play an instrument. INSTRUMENTS Note: Please DO NOT rent or purchase a PERCUSSION KIT until your child’s choice is confirmed. Students who choose PERCUSSION, will attend a Percussion Demo Lesson before their choice is confirmed. Instrument Choices are: BAND: Flute, Clarinet, Trumpet, Trombone, Baritone Horn and Percussion. th Important Notes: Saxophone will not be a vailable until 6 grade. Students who wish to play th SAXOPHONE should start on C LARINET in 5 grade. This year on clarinet prepares them for nd saxophone. Students who select percussi on should list a 2 choice. th ORCHESTRA: Violin, Viola and Cello. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Arnold Schoenberg Wind Quintet Op. 26 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Arnold Schoenberg Wind Quintet Op. 26 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Wind Quintet Op. 26 Country: US Released: 1978 Style: Modern MP3 version RAR size: 1884 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1453 mb WMA version RAR size: 1326 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 714 Other Formats: WAV DMF AIFF AA ASF TTA WMA Tracklist A1 First Movement: Schwungvoll 11:31 A2 Second Movement: Anmutig Und Heiter; Scherzando 8:17 B1 Third Movement: Etwas Langsam (Poco Adagio) 9:05 B2 Fourth Movement: Rondo 8:28 Credits Bassoon – Brian Pollard Clarinet – Piet Honingh Flute – Frans Vester Horn – Adriaan van Woudenberg Illustration – Kandinsky* Liner Notes – Alan Stout, Jeffrey Wasson Oboe – Maarten Karres Producer – Wolf Erichson Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Schoenberg*, Danzi Philips, Schoenberg*, PHC 9068 Quintet* - Wind Quintet, World PHC 9068 Canada 1967 Danzi Quintet* Opus 26 (LP, Album) Series Arnold Schönberg* - Danzi Quintett* - Arnold Schönberg* 64 812 Bläserquintett Op. 26 BASF 64 812 Germany 1975 - Danzi Quintett* (1923/24) (LP, Album, Club) Arnold Schönberg* - Arnold Schönberg* Danzi Quintett* - 25 22057-5 Acanta 25 22057-5 Germany Unknown - Danzi Quintett* Bläserquintett Op. 26 (LP, RE) Arnold Schönberg* - Arnold Schönberg* Danzi Quintett* - 25 22057-5 BASF 25 22057-5 Germany 1975 - Danzi Quintett* Bläserquintett Op. 26 (1923/24) (LP, Album) Arnold Schönberg* - Arnold Schönberg* 37 93007 Danzi Quintett* - BASF 37 93007 Spain 1976 - Danzi Quintett* Bläserquintett Op. 26 (LP) Related Music albums to Wind Quintet Op. 26 by Arnold Schoenberg Schönberg / Claude Helffer - Intégrale De L'Oeuvre Pour Piano Seul Messiaen, Schoenberg - Yvonne Loriod, Pierre Boulez - Sept Haïkaï / Kammersymphonie / 3 Orchesterstücke Paul Hindemith, Danzi-Quintett - Kleine Kammermusik Op. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 94, 1974-1975

THE FRIENDS OF THE COLLEGE Presents BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA, Music Director COLIN DAVIS, Principal Guest Conductor Ninty-fourth Season Monday evening, November 18, 1974 Tuesday evening, November 19, 1974 SEIJI OZAWA, Conductor William Neal Reynolds Coliseum 8 P.M. PROGRAM Le tombeau de Couperin Maurice Ravel Prelude Forlane Menuet Rigaudon Ostensibly this music represents neoclassic expression in its purest distillate. And it was, indeed, conceived as a pianistic idealization of the clavecin aesthetic exemplified by Francois Couperin le Crand. But that was in the fateful summer of 1914, and even Ravel's sleepy St. Jean-de-Luz was traumatized by the news of Archduke Francis Ferdinand's assassination at Sarajevo. France mobilized overnight, and by August was at war. By then the sketches for Le tombeau de Couperin were in a desk drawer. When he returned to them three wretched years later the composer was a very different man, broken in health and shattered emotionally by the loss of his mother, who had died barely a week after his medical discharge. Thus it was that the six movements became as many 'tomb- stones' (each one inscribed separately) for friends and regimental comrads who had been killed on the Western Front. As a work for solo piano—Ravel's last, incidentally—Le tombeau was not a notable success. Strictly speaking it could not have been because it marked a stylistic retrogression after the harmonic leaps forward in the Valse nobles et sentimentales and Gas-pard de la nuit. But fortu- nately that was not the end of the matter. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra

ABRAHAM cf ..."' c ="' HOODS UP TO THE AMERICAN WAY WITH WOOL Blanket plaid ... toggle terrific, either way you coat it this fall ... A&S says do it with pure wool fabric made in America! PURE WOOL® "The Wool mark is your assurance of a quality tested product made of pure wool" -----------------------------------OCTOBER, 1971 I BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC I 3 Thursday Evening, October 28, 1971 , 8:30 p.m. Subscription Performance The Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences presents the Boston Symphony Orchestra \X:'illiam Steinberg, Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas, Associate Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, Conducting Polonaise and Krakoviak from 'A Life for the Tsar' MIKHAIL GLINKA Symphony in C IGOR STRAVINSKY Mode.rato alia breve Larghetto concertante Allegretto Largo - tempo giu sto, alia breve IN TERMISSION Concerto for flute, oboe, piano and percussion EDISON DENISOV Overture: allegro moderato Cadenza: Iento rubato - allegro Coda: allegro giusto DORIOT ANTHONY DWYER, flute RALPH GOMBERG, oboe GILBERT KALISH, piano EVERETT FIRTH, percussion Symphony No. 2 in B minor, Op. 5 ALEXANDER BORODIN Allegro Scherzo: prestissimo - allegretto Andante Finale: allegro The Boston Symphony Orchestra records exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon. BALDWIN PIANO DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON AND RCA RECORDS 4 I BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC I OCTOBER, 1971 The Brooklyn Academy of Mus 1 c The t. Felix Street Corporation Administrative Staff Board of Directors : Harvey Lichtenstein, Director Seth S. Faison, Chairman Lewis L. Lloyd, General Manager Donald M. Blinken, President John V. Lindsay, Honorary Chairman Charles Hammock, Asst. General Manager M arti·n P. Carter Jane Yackel, Comptroller Barbaralce Diamonstein Thomas Kerrigan, Assistant to the Director Mrs. -

Faculty Woodwind Quartet Flyer Earl Boyd Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Music Programs The Earl Boyd Collection 2015 Faculty Woodwind Quartet Flyer Earl Boyd Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/earl_boyd_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Earl, "Faculty Woodwind Quartet Flyer" (2015). Music Programs. 29. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/earl_boyd_programs/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Earl Boyd Collection at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Programs by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 0 €astenn 1tt1nols Un1vens1ty w oo0w1n0 Quintet Dear Music Director: Your flutist, oboist, clarinetist, bassoonists, and hornists will welcome the opportunity to hear and work personally with the fine performers in the Eastern Illinois University Woodwind Quintet You are invited to write or call Rhoderick Key, Chairman, Music Department, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois, 61920 Phone 217-581-2917 Scheduled to suit your program FLUTE - Robert C. Snyder, flutist, frequent recitalist in Illinois and recent performer at Carnegie Recital Hall in New York, clinician, · writer, and band direetor, graduated from Indiana University with a Masters Degree in Woodwinds and complet~ his doctorate in History and Literature at University of Missouri at Kansas City. He has studied with Vallie Kirk at Washburn University of Topeka, James Pellerite at Indiana University, and William Kincaid. OBOE -Joseph Martin, oboist, double-reed specialist, recitalist, and clinician, graduated with his Masters Degree in Education from East Carolina University in North Carolina. Mr. Martin directs a University stage band and assists in the Symphony Orchestra program. -

Downbeat.Com September 2010 U.K. £3.50

downbeat.com downbeat.com september 2010 2010 september £3.50 U.K. DownBeat esperanza spalDing // Danilo pérez // al Di Meola // Billy ChilDs // artie shaw septeMBer 2010 SEPTEMBER 2010 � Volume 77 – Number 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser AdVertisiNg sAles Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] offices 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] customer serVice 877-904-5299 [email protected] coNtributors Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, How- ard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Jennifer -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 83,1963-1964, Trip

BOSTON • r . SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY /'I HENRY LEE HIGGINSON TUESDAY EVENING 4 ' % mm !l SERIES 5*a ?^°£D* '^<\ -#": <3< .4) \S? EIGHTY-THIRD SEASON 1963-1964 TAKE NOTE The precursor of the oboe goes back to antiquity — it was found in Sumeria (2800 bc) and was the Jewish halil, the Greek aulos, and the Roman tibia • After the renaissance, instruments of this type were found in complete families ranging from the soprano to the bass. The higher or smaller instruments were named by the French "haulx-bois" or "hault- bois" which was transcribed by the Italians into oboe which name is now used in English, German and Italian to distinguish the smallest instrument • In a symphony orchestra, it usually gives the pitch to the other instruments • Is it time for you to take note of your insurance needs? • We welcome the opportunity to analyze your present program and offer our professional service to provide you with intelligent, complete protection. invite i . We respectfully* your inquiry , , .,, / Associated with CHARLES H. WATKINS CO. & /qbrioN, RUSSELL 8c CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton / 147 milk street boston 9, Massachusetts/ Insurance of Every Description 542-1250 EIGHTY-THIRD SEASON, 1963-1964 CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra ERICH LEINSDORF, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Talcott M. Banks Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Abram Berkowitz Henry A. Laughlin Theodore P. Ferris John T. Noonan Francis W. Hatch Mrs. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 93, 1973-1974

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 THURSDAY A6 FRIDAY-SATURDAY 22 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President PHILIP K. ALLEN SIDNEY STONEMAN JOHN L. THORNDIKE Vice-President Vice-President Treasurer VERNON R. ALDEN MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK JOHN T. NOONAN ALLEN G. BARRY HAROLD D. HODGKINSON MRS JAMES H. PERKINS MRS JOHN M. BRADLEY E. MORTON JENNINGS JR IRVING W. RABB RICHARD P. CHAPMAN EDWARD M. KENNEDY PAUL C. REARDON ABRAM T. COLLIER EDWARD G. MURRAY MRS GEORGE LEE SARGENT ARCHIE C EPPS III JOHN HOYT STOOKEY TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. CABOT HENRY A. LAUGHLIN PALFREY PERKINS FRANCIS W. HATCH EDWARD A. TAFT ADMINISTRATION OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THOMAS D. PERRY JR THOMAS W. MORRIS Executive Director Manager PAUL BRONSTEIN JOHN H. CURTIS MARY H. SMITH Business Manager Public Relations Director Assistant to the Manager FORRESTER C. SMITH DANIEL R. GUSTIN RICHARD C. WHITE Development Director Administrator of Assistant to Educational Affairs the Manager DONALD W. MACKENZIE JAMES F. KILEY Operations Manager, Operations Manager, Symphony Hall Tanglewood HARRY NEVILLE Program Editor Copyright © 1974 by Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS ^H jgfism SPRING LINES" Outline your approach to spring. In greater detail with our hand- somely tailored, single breasted, navy wool worsted coat. Subtly smart with yoked de- tail at front and back. Elegantly fluid with back panel. A refined spring line worth wearing. $150. Coats. Boston Chestnut Hill Northshore Shopping Center South Shore PlazaBurlington Mall Wellesley BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 THE BOARD OF OVERSEERS OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC.