Source Vol. 57 Fall 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature Translation Fellowship Recipients Number of Grants: 24 of $12,500 Each Total Dollar Amount: $300,000

Fiscal Year 2020 Literature Translation Fellowship Recipients Number of Grants: 24 of $12,500 each Total Dollar Amount: $300,000 *Photos of the FY 2020 Translation Fellows and project descriptions follow the list below. Jeffrey Angles, Kalamazoo, MI . Nancy Naomi Carlson, Silver Spring, MD . Jessica Cohen, Denver, CO . Robyn Creswell, New York, NY . Marguerite Feitlowitz, Washington, DC . Gwendolyn Harper, Emeryville, CA . Brian T. Henry, Richmond, VA . William Maynard Hutchins, Todd, NC . Adriana X. Jacobs, New York, NY/Oxford, UK . Bill Johnston, Bloomington, IN . Elizabeth Lowe, Gainesville, FL . Rebekah Maggor, Ithaca, NY . Valerie Miles, Barcelona, Spain . Valzhyna Mort, Ithaca, NY . Armine Kotin Mortimer, Urbana, IL . Suneela Mubayi, New York, NY/Cambridge, UK . Greg Nissan, Tesuque, NM . Allison Markin Powell, New York, NY . Julia Powers, New Haven, CT . Frederika Randall, Rome, Italy . Sherry Roush, State College, PA . James Shea, Hong Kong . Kaija Straumanis, Rochester, NY . Spring Ulmer, Essex, NY Credit: Dirk Skiba Jeffrey Angles, Kalamazoo, MI ($12,500) To support the translation from the Japanese of the collected poems of modernist poet Nakahara Chūya. Chūya's poetry has been set to hundreds of pieces of music, ranging from classical art pieces to pop songs, and he has been the subject of biographies, studies, and creative pieces, including fiction, manga, and an opera libretto. Born in 1907, he published his first collection of poems, Songs of the Goat, when he was 27 and died at age 30 of cerebral meningitis, just before the release of his second book of poems, Songs of Days That Were. While some translations of his poems have appeared in anthologies, journals, and various books, all English translations of Chūya are long out of print. -

WILLIS BARNSTONE the POETICS of TRANSLATION - HISTORY, THEORY, PRACTICE New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993

WILLIS BARNSTONE THE POETICS OF TRANSLATION - HISTORY, THEORY, PRACTICE New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. 312 pp. In the preface to his Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson defined the lexicographer as "the humble drudge" who may not aspire to praise but only "hopes to escape reproach" (Johnson, 1788, a). Some eleven years ago, on the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Translator's Association, George Steiner echoed those words as they applied to the translator, declaring that "No literary translation will ever sastisfy those intimate with the original" (Times Literary Supplement, 1983: 1117). Not unlike Steiner's confession, the ineluctable dilemma "traduttore, traditore" was on the author's mind when, at the International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies, Harris Thomas posed the simple question: "Is translation possible?" (Thomas, 1990). Willis Barnstone tries to answer these questions in a well-thought- out book, that focuses on three issues and is, in reality, three volumes and a short essay, all bound in one. Part One (pp. 3-131), after a brief Introduction (pp. 3-14), deals with General Issues, i.e., "Problems and Parables" (pp. 15-131). Part Two (pp. 133-216) with "History: The Bible as Paradigm of Translation." Part Three (pp. 217-62) is an abridged course on the History of Translation, from the Greeks to our own times; Part Four (pp. 265-72), finally, is a very brief "ABC of Translating Poetry," stemming mostly from the author's own activity as a translator. Barnstone is not only a professor of comparative literature at Indiana University, but has cooperated with and been a translator for 118 such literary giants as Jorge Luis Borges and Octavio Paz. -

Latin American Literature in English Translation

FALL 2020 LATIN AMERICAN LITERATURE IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION RUTGERS UNIVERSTIY DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE STUDIES Professor: Patricio Ferrari Course number: Spanish 940:250:01 Classroom: CLASSES TAUGHT VIA BLACKBOARD Class time: TH 2:30-5:20PM Office: REMOTE VIA BLACKBOARD OR ZOOM Office Hours: TH 1-2PM (or by appointment) Contact: [email protected] Course Description In this introductory literature course, we will focus on a wide range of works by some of the most prominent Latin American authors (from pre-colonial Spanish times to the present day). We will explore the aesthetic trends and social concerns during major literary periods in Latin America (e.g., Hispanic Baroque and Hispanic Romanticism) and movements such as Modernismo––the first one to come out of Latin America. Given that literary works are not produced in a vacuum, we will examine the theoretical and historical backgrounds in which they emerged, and review the significant events some of these works allude to or memorialize. Our literary journey will take us through various genres, traditions, and themes (e.g., identity, displacement, memory, bilingualism/biculturalism, politics). This course includes poets and fiction writers from the following Latin American countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Nicaragua, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay. Latin American U.S.-based writers (Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico) will also integrate our syllabus. Since our readings and discussions will stem from texts in English translation, we will also address the role of translation––from both a practical and a theoretical point of view––as we compare and contrast different translation strategies, particularly in poetry. -

Spring 1970 Volume Iii Number 2

SPRING 1970/VOLUME Ill/NUMBER 2 Painting by David Whitehill MUNDUS ARTIUM A Journal of International Literature and the Arts Spring 1970, Volume 111, Number 2 Cover Photography by William G. Larson 1 MUNDUS ARTIUM STAFF Editor-in-Chief, Rainer 6chulte Associate Editor, Roma A. King, Jr. Assistant Editor, Tp.omas J. Hoeksema Assistant to the Editor, Lois Siegel ADVISORY BOARD Willis Barnstone, Ben Belitt, Michael Bullock, Glauco Cam• bon, Wallace Fowlie, Otto Graf, Walter Hollerer, Hans Egon Holthusen, Jack Morrison, Morse Peckham, Fritz Joachim von Rintelen, Austin Warren, Arvin Wells, J. Michael Yates. Mundus Artium is a journal of international literature and the arts, published three times a year by the department of English, Ohio University. Annual subscription $4.00; single copies $1.50 for United States, Canada, and Mexico. All other countries: $4.50 a year, and $1.75 for single copies, obtainable by writing to The Editors, Mundus Artium, Department of English, Ellis Hall, Box 89, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, U.S.A. 45701. Checks drawn on European accounts should be made payable to Kreissparkasse Simmern, 654 Simmern/Hunsriick, Germany, Konto Nr. 6047. Distributor for England: B.F. Stevens & Brown Ltd., Ardon House, Mill Lane, Godalming, Surrey, England. Manuscripts should be sent to the editors and should be accompanied by a self-addressed envelope with the appropriate return postage. Mundus Artium will consider for publication poetry, fiction, short drama, essays on literature and the arts, photography, and photographic reproductions of paintings and sculpture. It will include a limited number of book reviews. Copyright, 1970. Rainer Schulte and Roma A. -

Research.Pdf (755.1Kb)

“FOR GOOD WORK DO THEY WISH TO KILL HIM?”: NARRATIVE CRITIQUE OF THE ACTS OF PILATE A Thesis to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri Columbia, Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by JOHN DAVID SHANNON Dr. Steve Friesen, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2006 © Copyright by John David Shannon, 2006 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction to Topic and Thesis 3 History of the Text Dependence and Independence of Text Section 2: Anti-Semitism and the Acts of Pilate 15 Anti-Semitism in Early Christian Literature The Acts of Pilate Kernels, Satellites, and Plot Summary Section 3: Characters and Evaluative Point of View 28 Annas, Caiaphas, and the Jews Nicodemus: Figure and Jewish Authority Pilate: Outsider and Commentator Joseph of Arimathaea: Insider and Commentator Jesus Phinees, Adas, and Angaeus Other Witnesses Levi Summary Section 4: Conclusion 43 Appendix A: Satellites and Kernels 51 Bibliography 53 1 Section 1: Introduction to Topic and Thesis Generations of scholars have commented on the development of polemics against Jews in early Christian literature. For example, the Gospel of John does not differentiate between various factions among the Jewish assembly, as evident in the first century Gospel of Matthew’s use of titles like scribes and Pharisees, but unifies those opposed to the Christian movement as “Jews.” The trend of vilifying the Jews parallels the growth of second and third century literature exonerating Pontius Pilate and the Roman administration for the death of Jesus and destruction of Jerusalem.1 Again in John, Pilate declares his innocence in Jesus’ death three times and then turns him over to the Jewish assembly to be crucified, not Roman solders as witnessed in Mark, Matthew, and Luke. -

A Translation Legacy

MFA PROGRAM IN CREATIVE WRITING AND LITERARY TRANSLATION SPRING 2013 READING SERIES Trends in Translation Series: A Translation Legacy Poets and Translators Willis and Aliki Barnstone .POEBZ .BSDI rQN (PEXJO5FSOCBDI.VTFVN ,MBQQFS)BMM Aliki Barnstone is the author of seven books of poems, including Bright Body (White Pine, 2011) and Dear God, Dear Dr. Heartbreak: New and Selected Poems (Sheep Meadow, 2009), as well as a book of criticism, Changing Rapture: Emily Dick- inson’s Poetic Development (University Press of New England). She has edited two anthologies of women’s poetry, a book of literary critical essays, and an edition of H.D.’s Trilogy (New Directions, 1998), for which she wrote the introduction and readers’ notes. She also is the translator of The Collected Poems of C.P. Cavafy: A New Translation (W.W. Norton, 2006). In 2013, Carnegie Mellon University Press will reissue her book, Madly in Love, as a Carnegie-Mellon Classic Contemporary. She is currently Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Missouri–Columbia, where she serves as Series Editor of the Cliff Becker Book Prize in Translation. Willis Barnstone was educated at Bowdoin, Columbia, and Yale. He taught in Greece at the end of the civil war (1949–1951) and in Buenos Aires during the Dirty War, and during the Cultural Revolution went to China, where he was later a Fulbright Professor of American Literature at Beijing Foreign Studies University (1984–1985). He has published 70 books, including Modern European Poetry (Ban- tam, 1967); The Other Bible (HarperCollins, 1984); The Secret Reader: 501 Sonnets (New England, 1996); a memoir biography, With Borges on an Ordinary Evening in Buenos Aires (Illinois, 1993); and To Touch the Sky (New Directions, 1999). -

Read Book Literatures of Asia, Africa and Latin America from Antiquity to the Present 1St Edition

LITERATURES OF ASIA, AFRICA AND LATIN AMERICA FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE PRESENT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Willis Barnstone | 9780023060656 | | | | | Literatures of Asia, Africa and Latin America From Antiquity to the Present 1st edition PDF Book Of the journal's three languages, only Arabic, with a large African and Asian readership, is a language indigenous to the Third World; in some cases, however, a text may have been originally written in a fourth language, e. Carthage was probably not the earliest Phoenician settlement in the region; Utica may have predated it by half a century, and various traditions concerning the foundation of Carthage were current among the Greeks, who called the city Karchedon. Subscribe today. Top New Stories. Known as Works written in European languages date primarily from the 20th century onward. In this annotated translation and commentary, he restores the Latin, Greek, Aramaic, and Hebrew names to their original form. Accessed date. History at your fingertips. Set assignments easily to a whole class, differentiated groups or individual students. Science Teacher. In Roman times Punic beds, cushions, and mattresses were regarded as luxuries, and Punic joinery and furniture were copied. Views Read Edit View history. Slow in my shadow, with my hand I explore My invisible features. Science Coordinator. Although Punic wealth was legendary, the standard of cultural life enjoyed by the Carthaginians may have been below that of the larger cities of the Classical world. Arabic Standard. Print Cite. The high bar Barnstone has set for himself is the creation of an English-language Scripture that will move poets much as the King James Version moved Milton and Blake. -

Latin American Literature Office: L630; 718-260-5018 LATS 2202/, Section Office Hours

New York City College of Technology Instructor’s Name: Humanities Department Contact Email: Course Title: Latin American Literature Office: L630; 718-260-5018 LATS 2202/, Section Office Hours: SAMPLE SYLLABUS 3CL/3 CreditHours. CoursePrerequisite/ Co-requisite: ENG1101 or ENG1101CO or ENG1101ML. Flexible Core: World Cultures and Global Issues. REQUIRED MATERIAL Literatures of Latin America Author: Willis Barnstone • Paperback: 475 pages • Publisher: Longman (July 25, 2002) • Language: English • ISBN-10: 0130613606 • ISBN-13: 978-0130613608 • Product Dimensions: 5.9 x 1.4 x 8.9 inches COURSE DESCRIPTION The purpose of this course is to examine the development of Latin American literature and related visual documentation from the Pre-Columbian period to the present. We will read the course materials in terms of their historical and political context and examine literary forms, genres, and techniques. This course is designed for students interested in learning more about Latin American culture, expressed through literature, documentaries, and the visual arts. You will have the opportunity to appreciate works by prominent Latin American authors and exercise your own analytical and creative abilities. The course will be taught in English, but the instructor will reference the original texts in Spanish. Class activities are complemented by required online assignments. COURSE OBJECTIVES: • To sensitize students to the Latin American culture employing its literature, history, and artistic expressions. • To sensitize students to a cultural expression that might be different from their own. • To develop students' awareness of the cultural connections between Latin American and the United States. • To develop aesthetic sensitivity to literary/rhetorical structures. • To stimulate and develop students' critical thinking through class and group discussions and reflective writing. -

The Worlds of Langston Hughes

The Worlds of Langston Hughes The Worlds of Langston Hughes Modernism and Translation in the Americas VERA M. KUTZINSKI CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS Ithaca & London Copyright © 2012 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2012 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kutzinski, Vera M., 1956– The worlds of Langston Hughes : modernism and translation in the Americas / Vera M. Kutzinski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5115-7 (cloth : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-8014-7826-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Hughes, Langston, 1902–1967—Translations—History and criticism. 2. Hughes, Langston, 1902–1967—Appreciation. 3. Modernism (Literature)—America. I. Title. PS3515.U274Z6675 2013 811'.52—dc23 2012009952 Lines from “Kids in the Park,” “Cross,” “I, Too,” “Our Land,” “Florida Road Workers,” “Militant,” “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” “Laughers,” “Ma Man,” “Desire,” “Always the Same,” “Letter to the Academy,” “A New Song,” “Birth,” “Caribbean Sunset,” “Hey!,” “Afraid,” “Final Curve,” “Poet to Patron,” “Ballads of Lenin," “Lenin,” “Union,” “History,” “Cubes,” “Scottsboro,” “One More S in the U.S.A.,” and “Let America Be America Again” from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes by Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad with David Roessel, Associate Editor, copyright © 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of Alfred A. -

The New Covenant

"A breathtaking achievement."* THE NEW COVENANT Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jaar/issue/69/4 by guest on 27 September 2021 Commonly Called The New Testament Volume I: The Four Gospels and Apocalypse WILLIS BARNSTONE Newly translated from the Greek and Informed by Semitic Sources rom an award-winning poet and scholar of Greek and F Biblical Studies—a new trans- NEW lation of the four Gospels and Apocalypse that returns the bedrock COVENANT of Christianity to its origins as an outgrowth of Judaism. In place of Greek names, Barnstone restores probable Hebrew or Aramaic names to New Testament figures, and as in the Hebrew Bible, he lineates poetry as poetry. His translation of Apocalypse in blank verse reveals it as THE FOUR GOSPEIS'""1 APOCALYPSE the great epic poem of the New Testament. Notes. Bibliography. "Willis Barnstone has a problem: he's too good. Everything he writes, from his invaluable The Other Bible, a compendium of holy texts no writer should be without, through his brilliant translations and beautiful poems, is a breathtak- ing achievement."—Carolyn Kizer, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet* S Riverhead 576 pp. 1-57322-182-1 $35.00 PENGUIN PUTNAM INC. ACADEMIC HARKfTING DEPI. • 37S HUDSON SI. • NY. NY 1001065/ • www ptnij«inpulnjm (om The Voices of Mo re bath The Struggle for the Holy City Reformation and Rebellion in an Bernard Wasserstein English Village "This lucid and Eamon Duffy meticulously Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jaar/issue/69/4 by guest on 27 September 2021 researched book In this delightful book, we should be read by see—through anyone interested vividly detailed in the intractable parish records problem of kept from 1520 Jerusalem." to 1574 by the —David J. -

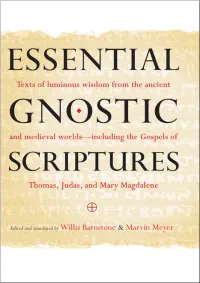

Essential Gnostic Scriptures

“Clear and luminous translations that capture the essence and poetic beauty of these iridescent texts. Essential Gnostic Scriptures provides further stepping-stones for seekers of wisdom and knowledge beyond the canonical testaments, or for those who are simply moved by great sacred poetry.” —Jeffrey Henderson, Editor, Loeb Classical Library “Fresh and remarkable readable translations of some of the most important gnostic books discovered in modern times, including the newly released Gospel of Judas. With its clear and up-to-date introduction to gnostics and their religion, Essential Gnostic Scriptures will be an invaluable resource for anyone interested in one of the most important religious movements of the ancient world.” —Bart D. Ehrman, author of Jesus, Interrupted and Lost Christianities ABOUT THE BOOK The people we’ve come to call gnostics were passionate advocates of the view that salvation comes through knowledge and personal experience, and their passion shines through in the remarkable body of writings they produced over a period of more than a millennium and a half. Willis Barnstone and Marvin Meyer have created a translation that brings the gnostic voices to us from across the centuries with remarkable power and beauty—beginning with texts from the earliest years of Christianity—including material from the Nag Hammadi library—and continuing all the way up to expressions of gnostic wisdom found within Islam and in the Cathar movement of the Middle Ages. The twenty-one texts included here serve as a compact introduction to Gnosticism and its principal ideas—and they also provide an entrée to the pleasures of gnostic literature in general, representing, as they do, the greatest masterpieces of that tradition. -

CCP Catalog 2019 Fall.Indd

though parallel lines touch in the infi nite, the infi nite is here— Arthur Sze Copper Canyon Reader 2020 “Poetry changes how we think.” Ellen Bass DEAR READER DEAR Dear Poetry Reader, Some things never change—like our dedication to poetry, and to you, the reader. But when Copper Canyon Press published our first poetry collection in 1973, • We typeset, printed, and bound each book by hand. • Phones weighed nearly five pounds and were attached to walls. • The word combinations “world wide web” and “search engine” did not yet carry meaning. As we celebrate the launch of our new website—five hundred titles and several decades of technological and cultural advances later—Copper Canyon Press is changing how we think. Specifically,we are changing how we think about getting books into the hands and hearts of those people we care deeply about: readers like you. One vestige of the old model of publishing—traditional direct sales—no longer serves our readers the way it used to. Sales through our catalog and website have become few and far between, with the vast majority of book purchases happening elsewhere. While we are thrilled by the myriad contemporary ways for readers to find and fall in love with poetry, we are pushed to think differently about what it means to operate sustainably. So we’ve decided to let our friends in retail do what they do best: sell books. That allows us to turn, with gratitude, to you, our community. This new Copper Canyon Reader introduces a new way of thinking: To directly support Copper Canyon Press, we invite you to Read Generously! Donate $35 or more to help sustain our nonprofit mission of publishing poetry, and we will be delighted to send you the book of your choice from among those featured within these pages.