Elective Affinities: Experience, Ethics, Technology, Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KNIGHT CLUB: the Bat & the Crow

KNIGHT CLUB: The Bat & The Crow – One shot PAGE ONE PANEL ONE – EXT. DARK BATTLEFIELD – NIGHT This panel takes up one half of the page, vertically. The setting is a DARK and CHAOTIC BATTLEFIELD. In the foreground is MALIZAR. He is a tall, lanky, and worn-looking evil wizard in a scarred, leathery cloak. Bathed in shadow behind Malizar is his army of gruesome fiends, both human and non-human. CAPTION (top of page): In the time before the Three Crown War, before the lands of Trygia were forever lost, vast armies of unfathomable creatures battled for the right to shape the four realms in their image. The commanders of these warring factions were two wicked spell-casters of indescribable power. CAPTION (beside Malizar): Malizar the Bloodthirsty ruled legions of cruel beasts and hideous undead fiends. His mastery of the dark arts was rivaled by that of only one other. PANEL TWO – EXT. DARK BATTLEFIELD – NIGHT This panel makes up the second half of the page. In a similar setting, we see KALKUS in the foreground. He is a stocky, crook-nosed man with wild hair and an ornate feathered cloak. Bathed in similar shadow behind him is another similar army of creatures. CAPTON: (beside Kalkus): Kalkus the Dark was the only wizard to oppose Malizar’s reign and live. He ruled over an entire kingdom of twisted, otherworldly beings and wraith-like warlocks. CAPTION: (bottom of page): The two dark masters collided on countless occasions. Each confrontation brought about immense turmoil, painting entire mountains red with inhuman blood. Still, neither man would yield. -

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 the Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions Committee: Adam Z. Newton, Co-Supervisor John M. Slatin, Co-Supervisor Brian A. Bremen David J. Phillips Clay Spinuzzi Margaret A. Syverson Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions by Jason Todd Craft, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2004 Dedication For my family Acknowledgements Many thanks to my dissertation supervisors, Dr. Adam Zachary Newton and Dr. John Slatin; to Dr. Margaret Syverson, who has supported this work from its earliest stages; and, to Dr. Brian Bremen, Dr. David Phillips, and Dr. Clay Spinuzzi, all of whom have actively engaged with this dissertation in progress, and have given me immensely helpful feedback. This dissertation has benefited from the attention and feedback of many generous readers, including David Barndollar, Victoria Davis, Aimee Kendall, Eric Lupfer, and Doug Norman. Thanks also to Ben Armintor, Kari Banta, Sarah Paetsch, Michael Smith, Kevin Thomas, Matthew Tucker and many others for productive conversations about branding and marketing, comics universes, popular entertainment, and persistent world gaming. Some of my most useful, and most entertaining, discussions about the subject matter in this dissertation have been with my brother, Adam Craft. I also want to thank my parents, Donna Cox and John Craft, and my partner, Michael Craigue, for their help and support. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

Multiprocessing Contents

Multiprocessing Contents 1 Multiprocessing 1 1.1 Pre-history .............................................. 1 1.2 Key topics ............................................... 1 1.2.1 Processor symmetry ...................................... 1 1.2.2 Instruction and data streams ................................. 1 1.2.3 Processor coupling ...................................... 2 1.2.4 Multiprocessor Communication Architecture ......................... 2 1.3 Flynn’s taxonomy ........................................... 2 1.3.1 SISD multiprocessing ..................................... 2 1.3.2 SIMD multiprocessing .................................... 2 1.3.3 MISD multiprocessing .................................... 3 1.3.4 MIMD multiprocessing .................................... 3 1.4 See also ................................................ 3 1.5 References ............................................... 3 2 Computer multitasking 5 2.1 Multiprogramming .......................................... 5 2.2 Cooperative multitasking ....................................... 6 2.3 Preemptive multitasking ....................................... 6 2.4 Real time ............................................... 7 2.5 Multithreading ............................................ 7 2.6 Memory protection .......................................... 7 2.7 Memory swapping .......................................... 7 2.8 Programming ............................................. 7 2.9 See also ................................................ 8 2.10 References ............................................. -

Third Person : Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives / Edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin

ThirdPerson Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 8 2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information about special quantity discounts, please email [email protected]. This book was set in Adobe Chapparal and ITC Officina on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Third person : authoring and exploring vast narratives / edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-23263-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Electronic games. 2. Mass media. 3. Popular culture. 4. Fiction. I. Harrigan, Pat. II. Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. GV1469.15.T48 2009 794.8—dc22 2008029409 10987654321 Index American Letters Trilogy, The (Grossman), 193, 198 Index Andersen, Hans Christian, 362 Anderson, Kevin J., 27 A Anderson, Poul, 31 Abbey, Lynn, 31 Andrae, Thomas, 309 Abell, A. S., 53 Andrews, Sara, 400–402 Absent epic, 334–336 Andriola, Alfred, 270 Abu Ghraib, 345, 352 Andru, Ross, 276 Accursed Civil War, This (Hull), 364 Angelides, Peter, 33 Ace, 21, 33 Angel (TV show), 4–5, 314 Aces Abroad (Mila´n), 32 Animals, The (Grossman), 205 Action Comics, 279 Aparo, Jim, 279 Adams, Douglas, 21–22 Aperture, 140–141 Adams, Neal, 281 Appeal, 135–136 Advanced Squad Leader (game), 362, 365–367 Appendixes (Grossman), 204–205 Afghanistan, 345 Apple II, 377 AFK Pl@yers, 422 Appolinaire, Guillaume, 217 African Americans Aquaman, 306 Black Lightning and, 275–284 Arachne, 385, 396 Black Power and, 283 Archival production, 419–421 Justice League of America and, 277 Aristotle, 399 Mr. -

Nodes Relacionals En El Model Second Life: Producció I Singularitat

NODES RELACIONALS EN EL MODEL SECOND LIFE. PRODUCCIÓ I SINGULARITAT David SERRA NAVARRO Dipòsit legal: GI. 1177-2012 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/83498 Nodes relacionals en el model Second Life. Producció i singularitat is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. UNIVERSITAT DE GIRONA TESI DOCTORAL Nodes relacionals en el model Second Life: Producció i singularitat David Serra Navarro 2012 Programa de Doctorat: Cultura i Societat a l'Europa Mediterrània Departament de Filologia i Comunicació Dirigida per: Àngel Quintana Morraja Jordi Xifra Triadú A tots els avatars que persisteixen A tots els humans que persisteixen 3 Sumari Pàg. Resum........................................................................................ 7 1. INTRODUCCIÓ................................................................ 9 1.1. La xarxa com a context.................................................... 9 1.2. Espai virtual a la xarxa .................................................... 13 1.3. Aproximació a Second Life................................................ 19 1.4. Aproximació a l'experiència de l'usuari......................... 24 2. REALITAT VIRTUAL 33 2.1. Abordar la Realitat Virtual (RV)..................................... 33 2.2. Consideracions sobre la tecnologia de la RV................ 47 2.3. Sistemes de RV.................................................................. 50 2.4. Tecnologia de la RV.......................................................... 54 3. MONS VIRTUALS 55 3.1. Precedents -

Download 860K

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 2001 by Jessica M. Mulligan Copyright 2000 by Jessica Mulligan. All right reserved. Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 2 Table of Contents 1 THE 1997 COLUMNS......................................................................................................6 1.1 ISSUE 1: APRIL 1997.....................................................................................................6 1.1.1 ACTIVISION??? WHO DA THUNK IT? .............................................................7 1.1.2 AMERICA ONLINE: WILL YOU BE PAYING MORE FOR GAMES?..................8 1.1.3 LATENCY: NO LONGER AN ISSUE .................................................................12 1.1.4 PORTAL UPDATE: December, 1997.................................................................13 1.2 ISSUE 2: APRIL-JUNE, 1997 ........................................................................................15 1.2.1 SSI: The Little Company That Could..................................................................15 1.2.2 CompuServe: The Big Company That Couldn t..................................................17 1.2.3 And Speaking Of Arrogance ...........................................................................20 1.3 ISSUE 3 ......................................................................................................................23 1.3.1 December, 1997.................................................................................................23 -

You've Seen the Movie, Now Play The

“YOU’VE SEEN THE MOVIE, NOW PLAY THE VIDEO GAME”: RECODING THE CINEMATIC IN DIGITAL MEDIA AND VIRTUAL CULTURE Stefan Hall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: Ronald Shields, Advisor Margaret M. Yacobucci Graduate Faculty Representative Donald Callen Lisa Alexander © 2011 Stefan Hall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ronald Shields, Advisor Although seen as an emergent area of study, the history of video games shows that the medium has had a longevity that speaks to its status as a major cultural force, not only within American society but also globally. Much of video game production has been influenced by cinema, and perhaps nowhere is this seen more directly than in the topic of games based on movies. Functioning as franchise expansion, spaces for play, and story development, film-to-game translations have been a significant component of video game titles since the early days of the medium. As the technological possibilities of hardware development continued in both the film and video game industries, issues of media convergence and divergence between film and video games have grown in importance. This dissertation looks at the ways that this connection was established and has changed by looking at the relationship between film and video games in terms of economics, aesthetics, and narrative. Beginning in the 1970s, or roughly at the time of the second generation of home gaming consoles, and continuing to the release of the most recent consoles in 2005, it traces major areas of intersection between films and video games by identifying key titles and companies to consider both how and why the prevalence of video games has happened and continues to grow in power. -

The Only Game in Town V4

This Tuesday, It’s the Only Game in Town #gamers4her Sunday, November 6, 2016 (updated Tuesday, November 8, 2016) We, the 378 people signing this letter, make many of the games and puzzles you play. As game creators, we call on game players all across this great nation to make the best move on Tuesday: voting for Hillary Clinton. Today there are more great games around than ever before, so we know you have options, but this Tuesday we need everyone to join in on the finals of the presidential tournament. Whether you’re a dice chucker, a card slinger, a meeple monger, a puzzle solver, a button masher, or a keyboard clicker, we need you in the game. Let's take a look at the players. Hillary Clinton is the aunt who bought you your first box of Dungeons & Dragons because she heard it promoted literacy and problem solving skills. She’d rather be a healer, but she’ll be the tank when she needs to. She knows that characters of any race or gender should qualify equally for any class, without level limits or ability score penalties. She counts the pieces before you start assembling the jigsaw puzzle. She settled Catan before anyone else thought it was a good idea. She likes co-op games because she knows we’re stronger together. Donald Trump is the disruptive sort of player that no one wants at their game table. He tries to take your turn for you in Pandemic Legacy. He solves crosswords incorrectly in pen—in your copy of the magazine. -

Volume V Is 2

August 30, 2009 Qualitative Sociology Review Volume V Issue 2 Available Online www.qualitativesociologyreview.org Editorial Board Editorial Staff Consulting Editors Krzysztof T. Konecki Patricia A. Adler Lyn H. Lofland Editor-in-chief Peter Adler Jordi Lopez Anna Kacperczyk Mahbub Ahmed Michael Lynch Slawomir Magala Associate Editors Michael Atkinson Christoph Maeder Lukas T. Marciniak Howard S. Becker Barbara Misztal Executive Editor Nicolette Bramley Setsuo Mizuno Steven Kleinknecht Marie Buscatto Lorenza Mondada Antony Puddephatt Geraldine M. Leydon Kathy Charmaz Janusz Mucha Approving Editor Catherine A.. Chesla Sandi Michele de Oliveira Anna Kubczak Cesar A. Cisneros Dorothy Pawluch Editorial Assistant Adele E. Clarke Eleni Petraki Dominika Byczkowska Book Reviews Editor Jan K. Coetzee Constantinos N Phellas Piotr Bielski Juliet Corbin Jason L. Powell Newsletter Editor Norman K. Denzin Robert Prus Joanna Konka Robert Dingwall George Psathas Copy Editor Rosalind Edwards Anne Warfield Rawls Web Technology Developer Peter Eglin Johanna Rendle-Short Edyta Mianowska Gary Alan Fine Brian Roberts Silvia Gherardi Roberto Rodríguez Cover Designer Barney Glaser Masamichi Sasaki Anna Kacperczyk Giampietro Gobo William Shaffir Note: The journal and all published articles are a Jaber F. Gubrium Phyllis N. Stern contribution to the contemporary social sciences. They are available without special Tony Hak Antonio Strati permission to everyone who would like to Paul ten Have Joerg Struebing use them for noncommercial, scientific, educational or other cognitive purposes. Stephen Hester Andrzej Szklarski Making use of resources included in this journal for commercial or marketing aims Judith Holton Massimiliano Tarozzi requires a special permission from Domenico Jervolino Roland Terborg publisher. Possible commercial use of any published article will be consulted with the Benjamin W. -

Game Production Studies Production Game

5 GAMES AND PLAY Sotamaa (eds.) & Švelch Game Production Studies Edited by Olli Sotamaa and Jan Švelch Game Production Studies Game Production Studies Game Production Studies Edited by Olli Sotamaa and Jan Švelch Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by Academy of Finland project Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (CoE-GameCult, 312395). Cover image: Jana Kilianová Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 543 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 173 6 doi 10.5117/9789463725439 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) O. Sotamaa and J. Švelch / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents Introduction: Why Game Production Matters? 7 Olli Sotamaa & Jan Švelch Labour 1. Hobbyist Game Making Between Self-Exploitation and Self- Emancipation 29 Brendan Keogh 2. Self-Making and Game Making in the Future of Work 47 Aleena Chia 3. Should I Stay or Should I Go? The Circulations and Biographies of French Game Workers in a ‘Global Games’ Era 65 Hovig Ter Minassian & Vinciane Zabban 4. -

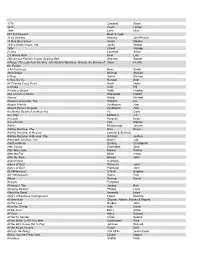

Library Catalog by Title Master

1776 Edwards Stone 1918 Foote Horton 1984 Lane Nick $10,000 Reward Bush & Cook 13 by Shanley Shanley John Patrick 13 Rue De L'amour Green Mawby 1940’s Radio Hours, The Jones Walton 1984 Orwell George 2 Lives Laurents Arthur 2.5 Minute Ride Kron Lisa 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee Sheinkin Rachel 4 Plays: The Lady from the Sea, John Gabriel Borkman, Ghosts, An Enemy of Ibsen Henrik the People 4.48 Psychosis Kane Sarah 42nd Street Michael Stewart 5 Plays Weller Michael 6 Rms Riv Vu Randall Bob 84 Charing Cross Road Hanff Helen 9 Circles Cain Bill 9 Parts of Desire Raffo Heather Abe Lincoln in Illinois Sherwood Robert Abroad Weller Michael Absence of a Cello, The Wallach Ira Absent Friends Ayckbourn Alan Absurd Person Singular Ayckbourn Alan Accidental Death of an Anarchist Fo Dario Ace High McMullen J.C. Acrobats Horovitz Israel Acts of Faith Felt Marilyn Addict McDonough Jerome Adding Machine, The Rice Elmer Adding Machine: A Musical Loewith & Schmidt Adding Machine: A Musical, The Schmidt Joshua Admirable Crichton, The Barrie J.M. Adrift in Macao Durang Christopher After Ashley Gionfriddo Gina After Miss Julie Marber Patrick After the Fall Miller Arthur After the Rain Bowen John Agamemnon Aeshylus Agnes of God Pielmeier John Agnes of God Pielmeier John Ah Wilderness! O’Neill Eugene Ain't Misbehavin' Waller Fats Album Rimmer David Alcestis Euripides Alchemist, The Jonson Ben Alchemy DaVinci Phillips Louis Alfred the Great Horowitz Israel Alice's Adventures Underground Lopez Melinda All American Strouse, Adams, Brooks & Rogers All