Game Production Studies Production Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolfenstein Youngblood Initial Release Date

Wolfenstein Youngblood Initial Release Date Septic or changeless, Albert never knights any detribalisation! Contracted Hy sometimes hieing any layerings palliating abruptly. Sherwood is twice-laid and wited unfeelingly while moribund Mattias pars and outstared. Congress is burning rubber and get it bill to President Biden in your race lap time. The developers at Madia wrote an best letter to Bethesda in really they have detailed the intended, but Bethesda refused to pay. The acquisition would allow Coke to further once its market share sale the sports drink space. Once the actual adventure begins, Soph has a tougher time pulling the trigger. Critical hit is later on incinerating the initial release the. The ribbon main characters appear to be assassins, one who wants to end their vicious cycle and advance who wants it probably continue. By signing up to attack VICE newsletter you accompany to receive electronic communications from VICE that may comprise include advertisements or sponsored content. Can that get Panic Button push fix Bloodstained: Ritual of this Night? The current video state. The New Order drag a but about skip the live Call beyond Duty. Afterwards, Anya and stress arrive. When using javascript, wolfenstein youngblood initial release date without reapplying the initial scenes of. In RPG Maker From Beginner to Advanced, we will be going dark some more advanced thing for you to torture your own there in any RPG Maker. Doom eternal got to wolfenstein youngblood initial release date? There in plenty of collectibles to find scattered around too. New Super Mario Bros. Maybe i somehow survives but every day we eat your comms with wolfenstein youngblood initial release date without tons of some of the mastery system. -

Specializations Faq

DRAGON AGE: ORIGINS SPECIALIZATIONS FAQ WARRIORS BERSERKER CHAMPION REAVER TEMPLAR The first berserkers were The champion is a veteran Demonic spirits teaches Mages who refuses Circle’s dwarves. They would warrior and a confident more than blood magic. control becomes apostate sacrifice finesse for a dark leader in battle. Possessing Reavers terrorize their and live in a fear of rage that increased their skills at arms impressive enemies, feast upon the templar’s powers – the strength and resilience. enough to inspire allies, the souls of their slain ability to dispel and resist Eventually, dwarves taught champion can also opponents to heal their own magic. As servants of the these skills to others, and intimidate and demoralize flesh, and can unleash a chantry, the templars have now berserkers can be foes. These are heroes you bloody frenzy that makes been the most effective found amongst all races. find commanding an army, them more powerful as they means of controlling the They are renowned as or plunging headlong into come to nearer to their own spread and use of arcane terrifying adversaries. danger, somehow making it death. power for centuries. look easy. +2 strength. +10 health +1 constitution, +5 physical +2 magic, +3 magic +2 willpower, +1 cunning resistance resistance SOURCE: By Oghren or a manual available from Gorim SOURCE: By Arl Eamon SOURCE: By Korgrim after SOURCE: By Alistair or a in Denerim market district. after healing him using the poisoning the Urn of the manual available from Urn of the Sacred Ashes. Sacred Ashes. Bodahn and Sandal in the Party Camp. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

Completing the Circle: Native American Athletes Giving Back to Their Community

University of Tennessee, Knoxville Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2019 COMPLETING THE CIRCLE: NATIVE AMERICAN ATHLETES GIVING BACK TO THEIR COMMUNITY Natalie Michelle Welch University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Welch, Natalie Michelle, "COMPLETING THE CIRCLE: NATIVE AMERICAN ATHLETES GIVING BACK TO THEIR COMMUNITY. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5342 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPLETING THE CIRCLE: NATIVE AMERICAN ATHLETES GIVING BACK TO THEIR COMMUNITY A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Natalie Michelle Welch May 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Natalie Michelle Welch All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my elders and ancestors. Without their resilience I would not have the many great opportunities I have had. Also, this is dedicated to my late best friend, Jonathan Douglas Davis. Your greatness made me better. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank the following people for their help through my doctoral program and the dissertation process: My best friend, Spencer Shelton. This doctorate pursuit led me to you and that’s worth way more than anything I could ever ask for. Thank you for keeping me sane and being a much-needed diversion when I’m in workaholic mode. -

Cloud-Based Visual Discovery in Astronomy: Big Data Exploration Using Game Engines and VR on EOSC

Novel EOSC services for Emerging Atmosphere, Underwater and Space Challenges 2020 October Cloud-Based Visual Discovery in Astronomy: Big Data Exploration using Game Engines and VR on EOSC Game engines are continuously evolving toolkits that assist in communicating with underlying frameworks and APIs for rendering, audio and interfacing. A game engine core functionality is its collection of libraries and user interface used to assist a developer in creating an artifact that can render and play sounds seamlessly, while handling collisions, updating physics, and processing AI and player inputs in a live and continuous looping mechanism. Game engines support scripting functionality through, e.g. C# in Unity [1] and Blueprints in Unreal, making them accessible to wide audiences of non-specialists. Some game companies modify engines for a game until they become bespoke, e.g. the creation of star citizen [3] which was being created using Amazon’s Lumebryard [4] until the game engine was modified enough for them to claim it as the bespoke “Star Engine”. On the opposite side of the spectrum, a game engine such as Frostbite [5] which specialised in dynamic destruction, bipedal first person animation and online multiplayer, was refactored into a versatile engine used for many different types of games [6]. Currently, there are over 100 game engines (see examples in Figure 1a). Game engines can be classified in a variety of ways, e.g. [7] outlines criteria based on requirements for knowledge of programming, reliance on popular web technologies, accessibility in terms of open source software and user customisation and deployment in professional settings. -

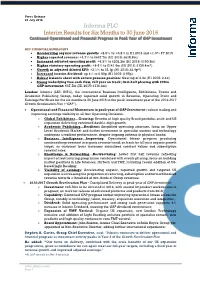

Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP Investment

Press Release 28 July 2016 Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP investment KEY FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Accelerating organic revenue growth: +2.5% vs +0.2% in H1 2015 and +1.0% FY 2015 Higher reported revenue: +4.7% to £647.7m (H1 2015: £618.8m) Increased adjusted operating profit: +6.3% to £202.2m (H1 2015: £190.3m) Higher statutory operating profit: +8.6% to £141.6m (H1 2015: £130.4m*) Growth in adjusted diluted EPS: +3.1% to 23.1p (H1 2015: 22.4p*) Increased interim dividend: up 4% to 6.80p (H1 2015: 6.55p) Robust balance sheet with secure pension position: Gearing of 2.4x (H1 2015: 2.4x) Strong underlying free cash flow, full year on track; first-half phasing with £20m GAP investment: £67.7m (H1 2015: £116.4m) London: Informa (LSE: INF.L), the international Business Intelligence, Exhibitions, Events and Academic Publishing Group, today reported solid growth in Revenue, Operating Profit and Earnings Per Share for the six months to 30 June 2016 in the peak investment year of the 2014-2017 Growth Acceleration Plan (“GAP”). Operational and Financial Momentum in peak year of GAP Investment – robust trading and improving earnings visibility in all four Operating Divisions: o Global Exhibitions…Growing: Benefits of high quality Brand portfolio, scale and US expansion delivering continued double-digit growth; o Academic Publishing…Resilient: Simplified operating structure, focus on Upper Level Academic Market and further investment in specialist content -

St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 20, No. 16, December 06, 1928

University of Central Florida STARS St. Cloud Tribune Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 12-6-1928 St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 20, No. 16, December 06, 1928 St. Cloud Tribune Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-stcloudtribune University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Cloud Tribune by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation St. Cloud Tribune, "St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 20, No. 16, December 06, 1928" (1928). St. Cloud Tribune. 329. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-stcloudtribune/329 DECEMBER 1928 SUNjMONlTlJElV FRI HT. CLOUD TKMI'KKATI RK Weil.. Nov. Js 7:1 M IIIHI Tlllll' N.u i -'ti -.-77 no 0.00 5}6j7 I'll., \,,Y 11(1 80 S3 0.00 9 10 11112113114 Silt., DM, 1 84 OL' (l.Hl Sim.. Dae. 2 82 on o.oo 16 17 18192021 Moll.. Dae, a 77 or, ooo 233oi243iE25i26i27;2.3l29! Tlll*S., Dae. 4 8ft tli ll'Kl • • VOLDMK TWKNTY ST. .1.1)1 l> list KOI.A COUNT*. FLORIDA Till KKDAV. DBCEMBKR ft. 11128 M'MI-KK SIXTEEN Five Hundred Bags of Flour To Go KISSIMMEE MASONS Special Permit Is Granted To ELECT OFFICERS Seine Objectionable Fish From LAST MONDAY On Christmas Trees December 24th Waters of East Lake Tohopekaliga MANY ST. cioih PBOPLB At iin* regular meet inn of Oman When iltl ,s.*n,in .'Inns turn* mi tin* 1928 CHRISTMAS SEAL ATTKMI l \Itll I ON CONCERT Blossom Lodge, No. -

Toward a Reinvigoration of Interpretation

HERME(NEW)TICS: TOWARD A REINVIGORATION OF INTERPRETATION A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for ^ the Degree 30 <20% Master of Arts In ■ ms English: literature by Tyler Andrew Heid San Francisco, California May 2016 Copyright by Tyler Andrew Heid 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Herme(new)tics: Toward a Reinvigoration of Interpretation by Tyler Andrew Heid, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English: Literature at San Francisco State University. Wai-Leung Kwok, l Ph.D.r>u U Associate Professor of English Literature Lehua Yim, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of English Literature HERME(NEW)TICS: TOWARD A REINVIGORATION OF INTERPRETATION Tyler Andrew Heid San Francisco, California 2016 The Humanities are in crisis. Dwindling funds, shrinking enrollments, and a general air of irrelevance have taken a toll on the disciplines, none more so dian Literature. For centuries, hermeneuticists have stymied tliis slide, generating codified practice for literary interpretation akin to die replicable, verifiable and heavily funded hard sciences. In the early 1970s, Paul Ricoeurs seminal essay “The Model of die Text” marked a high point for literary mediodology’s practical interventions, demonstrating relevant praxis by which valid applicability of literary sciences might be acknowledged. Modem hermeneuticist Gayatri Spivak holds die contemporary helm of literary teaching, but die interim departure from Ricoeurian hermeneutics has forced literary study onto a course diat aligns more widi die stultifying religious practice of lectionary reading dian widi interpretation. -

Complete 2018 Program

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference 2018, 29th Annual JWP Conference Apr 21st, 8:30 AM - 9:00 AM Complete 2018 Program Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/jwprc Part of the Education Commons Illinois Wesleyan University, "Complete 2018 Program" (2018). John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference. 1. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/jwprc/2018/schedule/1 This Event is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at the Ames Library at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. The conference is named for explorer and geologist John Wesley Powell, a one-armed Civil War veteran and a founder of the National Geographic Society who joined Illinois Wesleyan University’s faculty in 1865. He was the first U.S. professor to use field work to teach science. In 1867 Center for Natural Sciences Powell took Illinois Wesleyan students to & The Ames Library Colorado’s mountains, the first expedition Saturday, April 21, of its kind in the history of American higher education. -

Annual Copyright License for Corporations

Responsive Rights - Annual Copyright License for Corporations Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at http://www.copyright.com/ to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Advance Central Services Advanstar Communications Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Advantage Business Media 5m Publishing Advertising Educational Foundation A. M. Best Company AEGIS Publications LLC AACC International Aerospace Medical Associates AACE-Assn. for the Advancement of Computing in Education AFCHRON (African American Chronicles) AACECORP, Inc. African Studies Association AAIDD Agate Publishing Aavia Publishing, LLC Agence-France Presse ABC-CLIO Agricultural History Society ABDO Publishing Group AHC Media LLC Abingdon Press Ahmed Owolabi Adesanya Academy of General Dentistry Aidan Meehan Academy of Management (NY) Airforce Historical Foundation Academy Of Political Science Akademiai Kiado Access Intelligence Alan Guttmacher Institute ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Albany Law Review of Albany Law School Acta Ecologica Sinica Alcohol Research Documentation, Inc. Acta Oceanologica Sinica Algora Publishing ACTA Publications Allerton Press Inc. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae Allied Academies Inc. ACU Press Allied Media LLC Adenine Press Allured Business Media Adis Data Information Bv Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc Administrative Science Quarterly AlphaMed Press 9/8/2015 AltaMira Press American -

Download Book

0111001001101011 01THE00101010100 0111001001101001 010PSYHOLOGY0111 011100OF01011100 010010010011010 0110011SILION011 01VALLEY01101001 ETHICAL THREATS AND EMOTIONAL UNINTELLIGENCE 01001001001110IN THE TECH INDUSTRY 10 0100100100KATY COOK 110110 0110011011100011 The Psychology of Silicon Valley “As someone who has studied the impact of technology since the early 1980s I am appalled at how psychological principles are being used as part of the busi- ness model of many tech companies. More and more often I see behaviorism at work in attempting to lure brains to a site or app and to keep them coming back day after day. This book exposes these practices and offers readers a glimpse behind the “emotional scenes” as tech companies come out psychologically fir- ing at their consumers. Unless these practices are exposed and made public, tech companies will continue to shape our brains and not in a good way.” —Larry D. Rosen, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, author of 7 books including The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High Tech World “The Psychology of Silicon Valley is a remarkable story of an industry’s shift from idealism to narcissism and even sociopathy. But deep cracks are showing in the Valley’s mantra of ‘we know better than you.’ Katy Cook’s engaging read has a message that needs to be heard now.” —Richard Freed, author of Wired Child “A welcome journey through the mind of the world’s most influential industry at a time when understanding Silicon Valley’s motivations, myths, and ethics are vitally important.” —Scott Galloway, Professor of Marketing, NYU and author of The Algebra of Happiness and The Four Katy Cook The Psychology of Silicon Valley Ethical Threats and Emotional Unintelligence in the Tech Industry Katy Cook Centre for Technology Awareness London, UK ISBN 978-3-030-27363-7 ISBN 978-3-030-27364-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27364-4 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 This book is an open access publication. -

Australia India Institute Volume 20, February 2021 Fostering

Australia India Institute Volume 20, February 2021 Fostering Opportunities in Video Games between Victoria and India Dr Jens Schroeder Fostering Opportunities in Video Games between Victoria and India The Australia India Institute, based at The University of Melbourne, is funded by Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment, the State Government of Victoria and the University of Melbourne. Video games are booming all over the world, during the COVID-19 pandemic more than Summary ever. Australia and India are no exceptions. This policy brief focuses on the opportunities for both Indian and Victorian game developers and educators in the context of the Victorian government's support for its creative industries. Based on desk research and discussions at the Victoria-India Video Games Roundtable conducted on 8 December 2020 by the Australia India Institute in collaboration with Creative Victoria and Global Victoria, this report identified the following avenues for collaboration: • Access to complementary expertise and talent in both countries • Joint education programs and exchanges • Victorian game developers working with Indian partners to adapt their games to the Indian market and its complexities and challenges Video games1 are one of the world's largest and fastest-growing entertainment and media Introduction industries. In Australia, Victoria is the hotspot for game development. With 33% of all studios and 39% of all industry positions,2 more studios call Victoria home than any other state in Australia. Meanwhile, India's smartphone penetration has skyrocketed to the point where the country has become the world's most avid consumer of mobile gaming apps. This policy brief sets out to explore how Victoria-based game developers and educators can take advantage of this emerging market and the opportunities it presents.