Picture–Perfect Pairing: the Politics and Poetics of a Visual Narrative Program at Banteay Srei1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

@Ibet,@Binu^ Un! Lupun

@be @olbeddeg of jUnlis, @ibet,@binu^ un! luPun by Lawrcnce Durdin-hobertron Cesata Publications, Eire Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. The cover design. by Anna Durdin-Robertson. is a mandala oi a Chinese rlraqon goddess. Lawrence Durdln Rot,erlson. li_6 r2.00 Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. The Goddesses of India, Tibet, China and Japan Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. The Goddesses of India, Tibet, China and Japan by Lawrence Durdin-Robertron, M.A. (Dublin) with illustrations by Arna Durdin-Robertson Cesara Publications Huntington Castle, Clonegal, Enniscorthy. Eire. Printed by The Nationalist, Carlow. Eire. Anno Deae Cesara. Hiberniae Dominae. MMMMCCCXXIV Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. Thir serle. of books is written in bonour of The lrish Great Mother, Cessrs aod The Four Guardian Goddesses of lreland, Dsna, Banba' Fodhla and Eire. It is dedicated to my wife, Pantela. Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS I. The Goddesses of India'...'...'........"..'..........'....'..... I II. The Goddesses of Tlbet ............. ................."..,',,., 222 lll. Thc Goddesses of China ...............'..'..'........'...'..' 270 lV. The Goddesscs of Japan .........'.............'....'....'.. " 36 I List of abbreviations ....'........'...."..'...467 Bibfiogr.phy and Acknowledgments....'........'....'...,,,,.,'.,, 469 Index ................ .,...,.........,........,,. 473 Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. Copyrighted Material. All Rights Reserved. SECTION ONE The Goddesses of India and Tibet NAMES: THE AMMAS, THE MOTHERS. ETYMoLoGY: [The etymology of the Sanskrit names is based mainly on Macdonell's Sanskrit Dictionary. The accents denot- ing the letters a, i and 0 are used in the Egrmology sections; elsewhere they are used only when they are necessary for identification.] Indian, amma, mother: cf. Skr. amba, mother: Phrygian Amma, N. -

Temples Tour Final Lite

explore the ancient city of angkor Visiting the Angkor temples is of course a must. Whether you choose a Grand Circle tour or a lessdemanding visit, you will be treated to an unforgettable opportunity to witness the wonders of ancient Cambodian art and culture and to ponder the reasons for the rise and fall of this great Southeast Asian civili- zation. We have carefully created twelve itinearies to explore the wonders of Siem Reap Province including the must-do and also less famous but yet fascinating monuments and sites. + See the interactive map online : http://angkor.com.kh/ interactive-map/ 1. small circuit TOUR The “small tour” is a circuit to see the major tem- ples of the Ancient City of Angkor such as Angkor Wat, Ta Prohm and Bayon. We recommend you to be escorted by a tour guide to discover the story of this mysterious and fascinating civilization. For the most courageous, you can wake up early (depar- ture at 4:45am from the hotel) to see the sunrise. (It worth it!) Monuments & sites to visit MORNING: Prasats Kravan, Banteay Kdei, Ta Prohm, Takeo AFTERNOON: Prasats Elephant and Leper King Ter- race, Baphuon, Bayon, Angkor Thom South Gate, Angkor Wat Angkor Wat Banteay Srei 2. Grand circuit TOUR 3. phnom kulen The “grand tour” is also a circuit in the main Angkor The Phnom Kulen mountain range is located 48 km area but you will see further temples like Preah northwards from Angkor Wat. Its name means Khan, Preah Neak Pean to the Eastern Mebon and ‘mountain of the lychees’. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

Lalitha Sahasranamam

THE LALITHA SAHASRANAMA FOR THE FIRST TIME READER BY N.KRISHNASWAMY & RAMA VENKATARAMAN THE UNIVERSAL MOTHER A Vidya Vrikshah Publication ` AUM IS THE SYMBOL OF THAT ETERNAL CONSCIOUSNESS FROM WHICH SPRINGS THY CONSCIOUSNESS OF THIS MANIFESTED EXISTENCE THIS IS THE CENTRAL TEACHING OF THE UPANISHADS EXPRESSED IN THE MAHAVAKYA OR GREAT APHORISM tt! Tv< Ais THIS SAYING TAT TVAM ASI TRANSLATES AS THAT THOU ART Dedication by N.Krishnaswamy To the Universal Mother of a Thousand Names ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dedication by Rama Venkataraman To my revered father, Sri.S.Somaskandan who blessed me with a life of love and purpose ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Our gratitude to Alamelu and C.L.Ramakrishanan for checking the contents to ensure that they we were free from errors of any kin d. The errors that remain are, of course, entirely ours. THE LALITHA SAHASRANAMA LIST OF CONTENTS TOPICS Preface Introduction The Lalitha Devi story The Sri Chakra SLOKA TEXT : Slokas 1 -10 Names 1 - 26 Slokas 11 -20 Names 27 - 48 Slokas 21 -30 Names 49 - 77 Slokas 31 -40 Names 78 - 111 Slokas 41 -50 Names 112 - 192 Slokas 51 -60 Names 193 - 248 Slokas 61 -70 Names 249 - 304 Slokas 71 -80 Names 305 - 361 Slokas 81 -90 Names 362 - 423 Slokas 91 -100 Names 424 - 490 Slokas 101 -110 Names 491 - 541 Slokas 111 -120 Names 542 - 600 Slokas 121 -130 Names 601 - 661 Slokas 141 -140 Names 662 - 727 Slokas 141 -150 Names 728 - 790 Slokas 151 -160 Names 791 - 861 Slokas 161 -170 Names 862 - 922 Slokas 171 -183 Names 923 - 1000 Annexure : Notes of special interest ------------------------------------------------------------ Notes : 1. -

The Complete Mahabharata in a Nutshell

Contents Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 The Book of the Beginning 1.1 Vyasa (the Composer) and Ganesha (the Scribe) 1.2 Vyasa and his mother Sathyavathi 1.3 Janamejaya’s Snake Sacrifice (Sarpasastra) 1.4 The Prajapathis 1.5 Kadru, Vinatha and Garuda 1.6 The Churning of the Ocean of Milk 1.7 The Lunar and Solar races 1.8 Yayathi and his wives Devayani and Sharmishta 1.9 Dushyanta and Shakuntala 1.10 Parashurama and the Kshatriya Genocide BOOKS 1.11 Shanthanu, Ganga and their son Devavratha 1.12 Bhishma, Sathyavathi and Her Two Sons 1.13 Vyasa’s Sons: Dhritharashtra,DC Pandu and Vidura 1.14 Kunthi and her Son Karna 1.15 Birth of the Kauravas and the Pandavas 1.16 The Strife Starts 1.17 The Preceptors Kripa and Drona 1.18 The Autodidact Ekalavya and his Sacrifice 1.19 Royal Tournament where Karna became a King 1.20 Drona’s Revenge on Drupada and its Counterblow 1.21 Lord Krishna’s Envoy to Hasthinapura 1.22 The Story of Kamsa 1.23 The Wax Palace Inferno 1.24 Hidimba, Hidimbi and Ghatotkacha 1.25 The Ogre that was Baka 1.26 Dhaumya, the Priest of the Pandavas 1.27 The Feud between Vasishta and Vishwamithra 1.28 More on the Quality of Mercy 1.29 Draupadi, her Five Husbands and Five Sons 1.30 The Story of Sunda and Upasunda 1.31 Draupadi’s Previous Life 1.32 The Pandavas as the Incarnation of the Five Indras 1.33 Khandavaprastha and its capital Indraprastha 1.34 Arjuna’s Liaisons while on Pilgrimage 1.35 Arjuna and Subhadra 1.36 The Khandava Conflagaration 1.37 The Strange Story of the Sarngaka Birds Chapter 2 The Book of the Assembly Hall -

And ANGKOR WAT

distinctive travel for more than 35 years exotic VIETNAM and ANGKOR WAT CHINA Hong Kong Hanoi Ha Long Bay Haiphong THAILAND Gulf of Tonkin Hue Da Nang Chan May Hoi An South China Sea Angkor Wat Bangkok Siem Reap CAMBODIA UNESCO VIETNAM World Heritage Site Gulf of Saigon Cruise Itinerary Thailand Air Routing Land Routing Ha Long Bay Cruise through Vietnam and Cambodia, where lush Itinerary* landscapes and centuries-old culture are harmoniously linked, Hanoi u Ha Long Bay u Hôi An u Hué on this exceptional itinerary featuring two nights in Vietnam’s Saigon u Siem Reap u Angkor Wat capital city of Hanoi, an intriguing blend of French and Asian November 3 to 17, 2020 heritage, and a seven-night cruise from Haiphong to Saigon. End with three nights in Siem Reap, Cambodia, to experience Day the magnificent temples of Angkor Wat. Enjoy Five-Star 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada 2 Cross the International Date Line cruising aboard the exclusively chartered LE LAPEROUSÉ , 3-4 Hanoi, Vietnam launched in 2018 and featuring the Blue Eye, the world’s first multisensory, underwater Observation Lounge. Cruise the 5 Hanoi/Haiphong/Embark Le Lapérouse serene and storied shores of Vietnam, exploring its most 6 Ha Long Bay/Gulf of Tonkin captivating treasures, from tranquil ancient pagodas to bustling 7 Cruising the South China Sea harbors, and tour the jungle-fringed ruins of Cambodia, 8 Da Nang/Hôi An steeped in mystery yet also revealing testaments to religious, 9 Chan May/Hué imperial and artistic traditions. Featuring four UNESCO 10 Cruising the South China Sea World Heritage sites—Ha Long Bay, the Forbidden Purple 11 Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) City in Hué, Hôi An and the Temple of Angkor Wat—this 12 Saigon/Disembark ship/Fly to Siem Reap, Cambodia unique program is a spectacular blend of Southeast Asia’s 13 Siem Reap for Angkor Wat and Banteay Srei ancient world and dynamic modernity for an incredible value. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

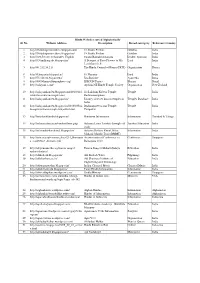

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Vietnam, Cambodia & the Mekong River

vietnam, cambodia & the mekong river 2018 - 2019 BEST RIVER CRUISE LINE, ASIA TABLE contentsOF Welcome A Mekong river cruise provides a unique perspective on one of the most exotic regions of the world. 2 OUR STORY There are wondrous things to be seen along this fabled river – ancient temples and robed monks, colorful markets and ethereal landscapes, elegant Colonial-era architecture and the warm smiles 3 THE MIGHTY MEKONG of the friendly Vietnamese and Cambodian people. 5 NAVIGATE THE MEKONG IN STYLE AmaWaterways takes pride in designing journeys that venture beyond the ordinary and provide a 7 A PALATE-PLEASING JOURNEY tantalizing mix of must-see sights and hidden gems. Our Vietnam and Cambodia itineraries feature authentic cultural encounters, enticing shore excursions and expert guides well-versed in Asian 9 THE COLORFUL CONTRASTS religions, architecture and history. You can experience it all from the comfort of the elegant AmaDara, OF VIETNAM which features twin-balcony staterooms and suites, along with an array of onboard amenities. 11 THE ALLURE OF CAMBODIA Generations of distinguished explorers have been drawn to the magic and mystery of Southeast 13 AUTHENTIC EXPERIENCES Asia. Join us and see this endlessly fascinating destination for yourself. We hope to welcome you aboard soon. 15 RICHES OF THE MEKONG 2 nights in Hanoi, 1 night in Ha Long Bay, Sincerely, 3 nights in Siem Reap, 7-night Prek Kdam to Ho Chi Minh City Cruise and 2 nights in Rudi Schreiner Kristin Karst Gary Murphy Ho Chi Minh City President Executive Vice President -

Shaiva Temples in Cambodia by Diglossia July 2014 Siva Worship In

Shaiva Temples in Cambodia By Diglossia July 2014 Siva worship in Southeast Asia has been recorded from the 3rd century CE, and the oldest known Linga in Southeast Asia has been found in present day Vietnam in the Mi Son group of temples. Inscriptions date it to 400 CE; it is known as the Siva Bhadresvara. Funan, (the predecessor to the kingdom of Cambodia) was, according to tradition, found by a Brahmin called Kaudinya who married the local Naga Princess. The capital of this kingdom was near the mountain, Ba Phnom, where the Shiva Linga was worshipped. Throughout the history of Cambodia, Pre-Angkor and later, the cult of Siva worship continues. Even during times of Buddhism as state religion, the presence of Brahmin priests, supervising the court rituals continues to this day. As such the temples found in Cambodia are to a large extent Siva temples, though the presiding deity now in all is Buddha. The history of Angkorian Cambodia begins with Jayavarman II in the year 802 CE. According to accounts by Arab traders, the Maharaja of Java had led an expedition against Cambodia, decapitated its king, and kept members of his family captive. The inscription of Sdok Kok Thom (11th century) tells of the return of King Jayavarman II from Java to reign in the city of Indrapura. The inscription gives an account of the king taking as his royal priest a Brahmin scholar named Sivakaivalya. Then the inscription records the king moving his capital to Kuti (present day Banteay Kdai), then to Hariharalya (where we have the Ruluos group of temple), next to Amarendrapura, and then to Mahendraparvata. -

Lord Shanmukha and His Worship

LORD SHANMUKHA AND HIS WORSHIP By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1950 Second Edition: 1974 Third Edition: 1996 (3,000 Copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Edition: 2000 WWW site: http://www.SivanandaDlshq.org/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7052-115-7 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. OM Dedicated to LORD SHANMUKHA The Consort of Valli, Deivayanai, The Destroyer of all Asuric Forces, and the Bestower of Divine Strength, Wisdom, Peace, Bliss and Immotality And to All His Devotees and Seekers in the Path of Truth. OM PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The Advent of Lord Skanda or Karttikeya, the purpose of His incarnation as an Avatara and its significance should be of great importance and of immense value to seekers after Truth. Lord Skanda, also known as Shanmukha, is adored and worshipped with intense faith and devotion throughout South India and Sri Lanka. And naturally it will be of great interest to all His devotees, in particular, to know more about Him, the significance of His birth and His life and career as a victorious General. Sri Swami Sivanandaji, the author of this book, graphically describes the above-mentioned subjects in his usual style,—inspiring and direct, instructive and illuminating, soul-elevating and at once impressive. It is needless to introduce him to the readers, who is so very well-known as a versatile genius in all the spiritual subjects and as an author of many an immortal and monumental work that breathes the spirit of ancient wisdom and of direct and intuitive realisation of the Supreme. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore