The Airport Concession Industry: Important Issues and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIRMALL USA's Media

GO WITH US CORPORATE OVERVIEW First launched at Pittsburgh International Airport in 1992, the AIRMALL is the gold standard for airport retail in the United States. Featuring a combination of popular international brands and high-quality local favorites, the AIRMALL model generates some of the highest per-passenger spends in the U.S. and regularly earns accolades for innovation and customer service. Travelers GO WITH US, because AIRMALL has developed proven strategies to improve airport concessions, increasing competition and enhancing the passenger experience. A better passenger experience means higher revenue for airports and more economic opportunity for business owners, job seekers and the community at large. AIRMALL USA is owned by Fraport Group, one of the leading groups in the international airport business. With Frankfurt Airport, the company operates one of the world's most important air transportation hubs. 1-800-ITS-FAIR • WWW.AIRMALL.COM • AIRMALL GO WITH THE FACTS CONTACT INFORMATION AIRMALL Boston 300 Terminal C Boston Logan International Airport Founded: 1991 Boston, MA 02128 P: 617-567-8881 • F: 617-567-0885 Number of Employees: 29 AIRMALL Cleveland Cleveland Hopkins International Airport CORPORATE LEADERSHIP Concourse B 5300 Riverside Drive • Kevin Romango – Chief Financial Officer Cleveland, OH 44135 • Jay Kruisselbrink – Senior Vice President P: 216-265-0700 • F: 216-265-1615 • Mike Caro – Vice President, AIRMALL Boston • Tina LaForte – Vice President, AIRMALL Cleveland AIRMALL Maryland • Brett Kelly – Vice President, AIRMALL Maryland P.O. Box 377 • Alan Gluck – Director of Business Development Linthicum, MD 21090 P: 410-859-9201 • F: 410-859-9204 CORE SERVICES AIRMALL Pittsburgh • Retail Property Development Pittsburgh International Airport • Leasing P.O. -

Silicon Valley Bank) 1\ M~Mt>Tr of SVB L'lrw~W Crwp Account Details Requested Date: From: 09/10/2015 To: 10/03/2015 Generated On: 10/15/2015

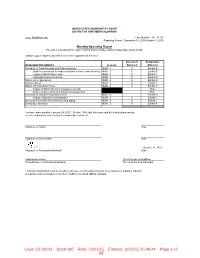

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA In re: NewZoom, Inc. Case Number: 15 - 31141 Reporting Period: September 10, 2015-October 3, 2015 Monthly Operating Report File with Court and submit copy to United States Trustee within 20 days after end of month Submit copy of report to any official committee appointed in the case. Document Explanation REQUIRED DOCUMENTS Form No. Attached Attached Schedule of Cash Receipts and Disbursements MOR - 1 X Exhibit A Bank Reconciliation (or copies of debtor's bank reconciliation's) MOR - 1 X Exhibit B Copies of Bank Statements MOR - 1 X Exhibit C Cash disbursements journal MOR - 1 X Exhibit D Statement of Operations MOR - 2 X Exhibit E Balance Sheet MOR - 3 X Exhibit F Status of Postpetition Taxes MOR - 4 X Exhibit G Copies of IRS Form 6123 or payment receipt None Copies of tax returns filed during reporting period None Summary of Unpaid Postpetition Debts MOR - 4 Exhibit H Listing of aged accounts payable MOR - 4 X Exhibit I Accounts Receivable Reconciliation and Aging MOR - 5 X Exhibit J Debtor Questionnaire MOR - 5 X Exhibit K I declare under penalty of perjury (28 U.S.C. Section 1746) that this report and the attached documents are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. Signature of Debtor Date Signature of Joint Debtor Date October 21, 2015 Signature of Authorized Individual* Date Andrew Hinkelman Chief Restructuring Officer Printed Name of Authorized Individual Title of Authorized Individual * Authorized individual must be an officer, director, or shareholder if debtor is a corporation; a partner if debtor is a partnership; a manager or member if debtor is a limited liability company. -

Fraport’S Recent Investment: a Questionable Platform for U.S

Fraport’s Recent Investment: A Questionable Platform for U.S. Growth AIRMALL USA – An Extensive Review Analyst: Ian Mikusko (212) 332-9330 [email protected] raport AG is a German-based airport owner and operator with its primary operation at FFrankfurt Airport. In August 2014, Fraport acquired airport concessions developer AIR- MALL USA, which currently stands as Fraport’s only investment in the North American mar- ket. Immediately following the acquisition, Fraport announced its intention to use AIRMALL as a platform for developing its U.S. business and to increase its U.S. brand exposure. This report examines whether AIRMALL is a suitable vehicle for growth in the U.S. market. AIRMALL is a concessions developer that is contracted to develop and manage food and retail programs at four U.S. airports. Unlike most companies in Fraport’s portfolio, AIRMALL does not manage entire airports. Rather, it manages airports’ food and retail concessions programs. Another difference is that AIRMALL operates in an airport industry that remains publicly owned. While many European airports have privatized, every airport in the continental United States is governed by state or local governments. AIRMALL is a relatively small company, holding concessions AIRMALL’s ability to win new business leases at just four airports. Fraport has stated its intention to and to maintain its existing accounts grow AIRMALL, thereby increasing Fraport’s own presence is a critical factor in considering and visibility in the market. AIRMALL’s ability to win new the prudence of Fraport’s AIRMALL business and to maintain its existing accounts is a critical factor investment. -

Appendix H Detailed Airport Case Studies

ACRP 01-14 Considering and Evaluating Airport Privatization Appendix H Appendix H Detailed Airport Case Studies H.1 Case Study Selections Case studies can be a useful means of illustrating first-hand experiences and lessons learned from those experiences. The purpose of this task is to document case studies to illustrate lessons learned for a range of airport sizes, privatization strategies, and forms of governance for both successful and unsuccessful efforts. For each case study, the research team documented (1) the initial goals and objectives of the airport sponsor for undertaking the privatization initiative, (2) a summary of the process employed, (4) a summary of the business terms of the initiative, (4) documentation of the experience to date, and (5) lessons learned. Literature reviews, transaction document reviews, and interviews were used to gather information for the case studies. Each case study considers the objectives, timeline, competitive bidding process, stakeholder interests, business terms, and the consequences (including development and operational experiences) and then presents lessons learned. It should be noted that, where the responses of individual interview participants are referred to in this report, these represent the interviewee’s own views and perceptions. However such responses have only been included to where they appear to represent opinions held more widely, or have been directly substantiated by other means On the basis of recommendations and justifications put forth by the research team, the ACRP Panel decided to ask the team to conduct case studies of the domestic and international airports as noted below. H.1.1 Domestic Airports Airport System Management Contract: 1. -

GREAT BRANDS THINK TWICE 2 3 AIRMALL: “Our Core Values Guide What We See As Our Corporate a Bad Responsibility

GREAT BRANDS THINK TWICE 2 3 AIRMALL: “Our core values guide what we see as our corporate A Bad responsibility. Operating responsibly — on the ground Fit for and in the sky is inseparable JetBlue from our success.” –JetBlue, The Blue Review 2014 4 5 An airline that can handle the fast-paced nature of this city and its people. An airline that promotes diversity, integrity and equal opportunity for all. An airline that is as unique as the city itself. What comes to mind New York thrives because it recognizes the value of opportunity when you think of and forward thinking. JetBlue has aspired to these values. JetBlue described New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport (JFK) as New York’s Hometown its ‘most significant’ lease agreement. Airline? JetBlue is currently considering contracting with AIRMALL, a German-owned concessions management company, at JFK Terminal 5. The following pages paint a picture of a company, AIRMALL, that falls short of the values that define New York and JetBlue. 6 7 Table of Contents “World-Class” Expectations ............10 Why would JetBlue undermine Millennials Not Malls .................12 its core values for a contract that Leaving Money on the Table ............16 won’t benefit New York, PIT: The “Gold” Standard ..............20 New Yorkers or New York’s CLE: Rent Reductions .................24 Hometown Airline? Racial Inequality .....................26 Labor Unrest ........................28 AIRMALL is a Bad Fit for JetBlue. Political Headaches ..................32 Stagnation Since ’08 ..................38 8 9 JetBlue’s -

Dining & Nightlife

Dining & Nightlife Printed: 4/30/2015 Airmall Pittsburgh PO Box 12318 Pittsburgh International Airport Pittsburgh, PA 15231 Phone: 412-472-5180 Mobile: Fax: 412/472-5190 Primary Contact: Mr. Jay Kruisselbrink Vice President of Development Website: www.airmall.com [email protected] 80+ shops and restaurants all at regular mall prices...guaranteed and all at the Pittsburgh International Airport.<br /> All India 315 N. Craig St. Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Phone: 412-681-6600 Mobile: Fax: Primary Contact: Mr. Didar Singh Owner Website: www.allindiapgh.com [email protected] Alla Famiglia 804 E. Warrington Ave. Pittsburgh, PA 15201 Phone: 412-488-1440 Mobile: Fax: Primary Contact: Mr. Chris Vlasic Product Manager Website: www.allafamigliapittsburgh.com, www.allafamigliabrand.com [email protected] Relax and enjoy the finest steaks, chops and seafood in an old world intimate setting. Alla Famiglia and its staff will deliver you Italian cooking with love and exemplary service.<br /> <br /> Alla Famiglia 804 E. Warrington Ave.804 E. Warrington Ave. Pittsburgh, PA 15201 Phone: 412-488-1440 Mobile: Fax: Category Contact: Mr. Chris Vlasic Product Manager Website: www.allafamigliapittsburgh.com, www.allafamigliabrand.com [email protected] Relax and enjoy the finest steaks, chops and seafood in an old world intimate setting. Alla Famiglia and its staff will deliver you Italian cooking with love and exemplary service.<br /> <br /> Altius 1230 Grandview Ave. Pittsburgh, PA 15211 Phone: 412-904-4442 Mobile: Fax: Category Contact: Ms. Christine Charles Director of Private Dining & Website: www.altiuspgh.com Events [email protected] Fresh.Simple.Honest. At Altius, every detail of your visit is an opportunity to create a sublime, elevated experience. -

United States Bankruptcy Court

Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 290 Filed 08/31/18 Page 1 of 40 Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 290 Filed 08/31/18 Page 2 of 40 EXHIBIT A Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 290 Filed 08/31/18 Page 3 of 40 Brookstone Holdings Corp. - Service List to e-mail Recipients Served 8/30/2018 AKIN GUMP STRAUSS HAUER & FELD LLP AKIN GUMP STRAUSS HAUER & FELD LLP AKIN GUMP STRAUSS HAUER & FELD LLP ALLISON MILLER ERIK PREIS JASON RUBIN [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ARCHER & GREINER, P.C. ARCHER & GREINER, P.C. ASHBY & GEDDES, P.A. ALEXANDER FARIS DAVID CARICKHOFF KAREN SKORMORUCHA OWENS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BALLARD SPAHR LLP BAYARD, P.A. BAYARD, P.A. DAVID L. POLLACK ERIN R. FAY GREGORY J. FLASSER [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BAYARD, P.A. BEWLEY, LASSLEBEN & MILLER, LLP BUCHALTER, A PROFESSIONAL CORPORATION JUSTIN R. ALBERTO ERNIE PARK SHAWN M. CHRISTIANSON [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BURR & FORMAN LLP CHOATE, HALL & STEWART LLP CHOATE, HALL & STEWART LLP J. CORY FALGOWSKI JONATHAN D. MARSHALL KEVIN SIMARD [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] CITY OF PHILADELPHIA LAW DEPARTMENT COOLEY LLP COOLEY LLP MEGAN HARPER CATHY HERSHCOPF EVAN LAZEROWITZ [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] COOLEY LLP COOLEY LLP COOLEY LLP ROBERT WINNING SETH VAN AALTEN SUMMER MCKEE [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] COUNTY OF LOUDOUN, VIRGINIA DLA PIPER LLP DLA PIPER LLP STEVEN F. -

The New Airport Corridor

THE MAGAZINE OF THE MASTER BUILDERS’ ASSOCIATION OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2014 THE NEW AIRPORT CORRIDOR Assessing Act 89 Mechanics Lien Revised Again Third Quarter Results Build with a leader. Be proud of the results. On the surface, you see a magnifi cent building, highway or bridge. What you may not see are the leadership and values that constructed the building and paved the highway, or the commitment to safety that guided those projects to successful completion. Visit pjdick. com to learn how our dedication to sustainable building, innovative technology, quality construction and safety can bring your next project to life. Together let’s safely build a project we can all be proud of. @PJDickinc | facebook.com/PJDickinc A Drug Free Equal Opportunity Employer PJD_Ad_Build_with_7_3.indd 1 7/3/14 11:03 AM Pantone CMYK Web Safe (RGB) 3308 143 5773 Cool Gray 6 100:0:60:72.16 0:35:85:0 9:0:43:38 0:0:0:31 01:48:3A FB:B0:40 9E:A3:74 BA:BC:BE CONTENTS 2014 About the Cover: PUBLISHER I-376 Airport Corridor Tall Timber Group Photo by www.talltimbergroup.com BreakingGround EDITOR Jeff Burd 412-366-1857 [email protected] PRODUCTION Carson Publishing, Inc. Kevin J. Gordon ART DIRECTOR/GRAPHIC DESIGN Carson Publishing, Inc. Jaimee D. Greenawalt CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Anna Burd CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHY Next Architecture Mascaro Construction ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Karen Kukish 412-837-6971 07 REGIONAL MARKET 49 MBE/WBE [email protected] COMPANY SPOTLIGHT 13 NATIONAL MARKET RWIW Construction LLC MORE INFORMATION: BreakingGround is published by 17 WHAT’S IT COST? 52 TREND TO WATCH Tall Timber Group for the Master Assessing the impact of Act 89. -

Luxury Shopping Destinations Kiehl's and Tumi Now Open at The

Luxury Shopping Destinations Kiehl’s and Tumi Now Open at the AIRMALL® at BWI Marshall — Travelers Can Shop at New High-End Retailers on the B/C Connector — AIRMALL® USA, the leading airport concessions developer in North America and operator of the AIRMALL at Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI Marshall), is offering travelers two new luxury shopping destinations with the opening of Kiehl’s (627 sq. ft) and Tumi (587 sq.ft.) on the B/C Connector. “Today’s traveler wants a variety of shopping options at the airport, including luxury retail and brands that they know and trust,” said Brett Kelly, vice president of AIRMALL Maryland. “Kiehl’s and Tumi bring premium products for the discerning shopper, and we’re very pleased to welcome these new brands to the program.” Kiehl’s offers travelers a selection of premium skin, hair and body care products. For 160 years, Kiehl’s has taken an old-world apothecary approach to skin care, with products made from the finest naturally- derived ingredients. The new store’s interior at BWI Marshall is funky and eclectic and includes brick, wood, and leather finishes. Travelers are welcomed into the store by Mr. Bones, Kiehl’s famous lab coat clad skeleton mascot. Kiehl’s is operated by Olde Mill, the same operator that brings Swarovski and America! to the AIRMALL at BWI Marshall. For more than 30 years, Tumi has been recognized as one of the world's leading designers of high-quality, luxury travel, business and lifestyle accessories. Passengers at the AIRMALL at BWI Marshall can purchase a wide variety of travel essentials, including luggage, messenger bags, totes, and other accessories. -

ACRP Report 66 – Considering and Evaluating Airport Privatization

124 pages; Perfect Bind with SPINE COPY (can reduce type to 12 pts) AIRPORT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH ACRP PROGRAM REPORT 66 Sponsored by the Federal Aviation Administration Considering and Evaluating Airport Privatization ACRP OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE* TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2012 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE* CHAIR OFFICERS James Wilding CHAIR: Sandra Rosenbloom, Professor of Planning, University of Arizona, Tucson Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority VICE CHAIR: Deborah H. Butler, Executive Vice President, Planning, and CIO, Norfolk Southern (retired) Corporation, Norfolk, VA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board VICE CHAIR Jeff Hamiel MEMBERS Minneapolis–St. Paul Metropolitan Airports Commission J. Barry Barker, Executive Director, Transit Authority of River City, Louisville, KY William A.V. Clark, Professor of Geography and Professor of Statistics, Department of Geography, MEMBERS University of California, Los Angeles James Crites Eugene A. Conti, Jr., Secretary of Transportation, North Carolina DOT, Raleigh Dallas–Fort Worth International Airport James M. Crites, Executive Vice President of Operations, Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, TX Richard de Neufville Paula J. C. Hammond, Secretary, Washington State DOT, Olympia Massachusetts Institute of Technology Michael W. Hancock, Secretary, Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, Frankfort Kevin C. Dolliole Chris T. Hendrickson, Duquesne Light Professor of Engineering, Carnegie-Mellon University, Unison Consulting Pittsburgh, PA John K. Duval Adib K. Kanafani, Professor of the Graduate School, University of California, Berkeley Austin Commercial, LP Gary P. LaGrange, President and CEO, Port of New Orleans, LA Kitty Freidheim Michael P. Lewis, Director, Rhode Island DOT, Providence Freidheim Consulting Susan Martinovich, Director, Nevada DOT, Carson City Steve Grossman Jacksonville Aviation Authority Joan McDonald, Commissioner, New York State DOT, Albany Kelly Johnson Michael R. -

Nature's Kitchen Fresh Café Brings Even More Wholesome

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jeff Donaldson 412.642.7700 [email protected] Nature’s Kitchen Fresh Café Brings Even More Wholesome Goodness to the AIRMALL® at Pittsburgh International Airport – Café Focused on Freshness Opens First of Three New Units – PITTSBURGH, May 25, 2010 – A wide selection of freshly prepared, organic, wholesome meals has been added to the menu at the AIRMALL® at Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT). BAA Pittsburgh, developer of the AIRMALL® at PIT, is pleased to welcome Nature’s Kitchen Fresh Café to the award-winning airport concessions program. Nature’s Kitchen Fresh Café has opened a landside unit, the first of three units that are becoming part of the concessions program. “Nature’s Kitchen is committed to preparing and serving fresh food…the way nature meant it to be. Their dedication to freshness and to using natural ingredients closely correlates with what travelers are seeking when they are on the go,” said Jay Kruisselbrink, vice president of BAA Pittsburgh. “We are certain that Nature’s Kitchen Fresh Café will only enhance our concessions program, one that is founded on the concept of ‘Regular Mall Prices…Guaranteed.’ No mark- ups. Just a quality meal at a fair price.” Nature’s Kitchen Fresh Café features a full menu for airport visitors and passengers – wholesome dishes, freshly-made juices, salads, handcrafted sandwiches, wraps, soups, entrees and desserts. The concept relies on only the very best local produce whenever possible and incorporates organic ingredients into its dishes for unmistakable quality and taste. – more – BAA Pittsburgh – Nature’s Kitchen – Page 2 Nature’s Kitchen Fresh Café Brings Even More Wholesome Goodness to the AIRMALL® at Pittsburgh International Airport (cont.) – Café Focused on Freshness Opens First of Three New Units – The AIRMALL® at PIT remains the gold standard for airport retail concessions across the nation. -

Case in Point 2

iop case in point 2 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH INSTITUTE OF POLITICS case in point PINK SLIP: Southwestern Pennsylvania’s Response to Workforce Reductions at US Airways, 2001–05 by Jenny Wolsk Bain SEPTEMBER 2006 The tragic events of 3 University of Pittsburgh September 11, 2001, exacerbated a downward turn in the U.S. airline industry that resulted in significant layoffs. This Case in Point examines how Southwestern Pennsylvania responded to a five-year series of massive job losses at one of the region’s largest employers, US Airways. iop case in point 1 The unforgettable events of September 11, 2001, In addition to causing financial hardship, the layoffs delivered a crushing blow to the U.S. airline industry, triggered feelings of anger, hopelessness, and anxiety which was already in a financially precarious position. among many dislocated workers and their families. Long after the temporary shutdown was over and Aftershocks reverberated throughout the community. operations had resumed, many people were reluctant “The impact was tremendous in my district,” says to travel. The resulting loss of revenue, coupled with State Senator John Pippy (R-Moon Township). “Every- increased costs associated with new security measures, one knew someone who was personally affected.” caused several major carriers to take drastic actions, Pittsburgh-area leaders, well aware of the potentially including significant layoffs. devastating impact of a major dislocation on the region, Southwestern Pennsylvania was hit particularly launched a multi-pronged response to the US Airways hard. Between 2001 and 2005, 8,400 US Airways layoffs, with dozens of public and private agencies employees lost their jobs, including pilots, flight atten- involved in the planning and delivery of services to dants, mechanics, maintenance workers, reservation affected workers.