ACRP Report 66 – Considering and Evaluating Airport Privatization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noise Abatement Procedures

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, DAVIS BERKELEY • DAVIS • IRVINE • LOS ANGELES • MERCED • RIVERSIDE • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO SANTA BARBARA • SANTA CRUZ TRANSPORTATION AND PARKING SERVICES ONE SHIELDS AVENUE TELEPHONE: (530) 752-8277 DAVIS, CALIFORNIA 95616 FAX: (530) 752-8875 July 8, 2009 CC09-023 TO: Pilots utilizing University Airport (KEDU) RE: University Airport Noise Abatement Program This letter serves to update and clarify the Noise Abatement Program for University Airport and supersedes all previous letters pertaining to recommend noise abatement procedures. The University of California, Davis intends that University Airport be regarded as a “Good Neighbor” by the surrounding community. For pilots, this means minimizing the noise impact of flight operations on adjacent residential areas for all arrivals and departures, as well as for training/proficiency flights. Compliance with noise abatement procedures, while strongly encouraged, is always voluntary and operational safety always takes precedence. Generally The residential area north of the airport (bounded by Russell Boulevard on the south) is the most noise sensitive area in the vicinity of the airport. For arrivals, a well executed left hand rectangular traffic pattern, as described in the FAA Aeronautical Information Manual, is generally sufficient for noise abatement procedures. Straight in approaches to Runway 35 are also acceptable. Runway 17 departures require no special procedures. Runway 35 departures should comply with bullet point 7 below. University Airport does NOT have a designated calm wind runway. Pilots are expected to take off and land into the prevailing wind. In the event of a calm wind condition, pilots are encouraged to include noise abatement considerations in the selection of a departure or arrival runway. -

Ceqa Findings Page 2

Attachment 9 CALIFORNIA ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY ACT FINDINGS IN CONNECTION WITH THE APPROVAL OF THE CHEMISTRY ADDITION AND FIRST FLOOR RENOVATION PROJECT, DAVIS CAMPUS I. ADDENDUM TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS 2018 LONG RANGE DEVELOPMENT PLAN FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT FOR THE BAINER HALL AND CHEMISTRY COMPLEX ADDITION AND RENOVATIONS PROJECT DATED FEBRUARY 2019 The Board of Regents of the University of California (“University”), as the lead agency pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (“CEQA”), prepared an Addendum (“Addendum February 2019”) to the Final Environmental Impact Report (“EIR”) for the University of California, Davis (“UC Davis”) 2018 Long Range Development Plan (“2018 LRDP”) (State Clearinghouse No. 2017012008) for the Bainer Hall and Chemistry Complex Addition and Renovations Project (“Project”) to document that no subsequent or supplemental EIR to the 2018 LRDP EIR is necessary to evaluate the environmental impacts of the Project pursuant to CEQA. The 2018 LRDP EIR was certified by the University in July 2018. The Addendum was completed in February 2019 (“Addendum February 2019”) in compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act, Public Resources Code Sections 21000, et seq. (“CEQA”) and the State CEQA Guidelines, Title 14, California Code of Regulations, Sections 15000 et seq. ("CEQA Guidelines"). Addendum February 2019 evaluated whether any of CEQA’s conditions requiring the preparation of a subsequent or supplemental EIR in connection with the Project are present. The University has examined the Project, in light of the environmental analysis contained in the 2018 LRDP EIR, and has determined that all of the potential environmental effects of the Project are fully evaluated in the 2018 LRDP EIR. -

Employees at Atsg Companies Raise Over $64,000 for Charity

EMPLOYEES AT ATSG COMPANIES RAISE OVER $64,000 FOR CHARITY WILMINGTON, OH - January 16, 2013 – During their annual fundraising drive to benefit local charities, employees of Air Transport Services Group, Inc. and its subsidiaries at Wilmington Air Park raised $64,640 in pledges and donations, including a $10,000 corporate contribution from ATSG. ABX Air, Airborne Maintenance & Engineering Services (AMES), and LGSTX Services are among the ATSG subsidiaries based at Wilmington Air Park. The drive allows employees to divide their donation as desired among several charities, including the United Way of Clinton County, the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, and local food pantries. "Year after year our employees step up to the plate to help fund the important role these organizations fill in our community," said company spokesperson Paul Cunningham. The company has organized an annual charity drive every year since 1984. In addition to giving through payroll deduction, employees also created and raffled off gift baskets, cooked meals, held bake sales, and competed in a variety of fundraising contests. Proceeds from the events were split equally among the charities. About ABX Air, Inc. ABX Air (www.abxair.com) is an FAR Part 121 cargo airline headquartered in Wilmington, Ohio, with a thirty-year history of flying express cargo routes for customers in the U.S. and around the world. About Airborne Maintenance & Engineering Services, Inc. AMES (www.airbornemx.com) is a one-stop aircraft maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) provider operating out of Wilmington, Ohio, with additional line maintenance operations in Cincinnati, Ohio and Miami, Florida. AMES holds a Part 145 FAA Repair certificate and provides heavy maintenance, line maintenance, material sales and service, component repair and overhaul, and engineering services to aircraft operators. -

Notice of Adjustments to Service Obligations

Served: May 12, 2020 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR SERVICE PURSUANT TO PUBLIC LAW NO. 116-136 §§ 4005 AND 4114(b) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 NOTICE OF ADJUSTMENTS TO SERVICE OBLIGATIONS Summary By this notice, the U.S. Department of Transportation (the Department) announces an opportunity for incremental adjustments to service obligations under Order 2020-4-2, issued April 7, 2020, in light of ongoing challenges faced by U.S. airlines due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency. With this notice as the initial step, the Department will use a systematic process to allow covered carriers1 to reduce the number of points they must serve as a proportion of their total service obligation, subject to certain restrictions explained below.2 Covered carriers must submit prioritized lists of points to which they wish to suspend service no later than 5:00 PM (EDT), May 18, 2020. DOT will adjudicate these requests simultaneously and publish its tentative decisions for public comment before finalizing the point exemptions. As explained further below, every community that was served by a covered carrier prior to March 1, 2020, will continue to receive service from at least one covered carrier. The exemption process in Order 2020-4-2 will continue to be available to air carriers to address other facts and circumstances. Background On March 27, 2020, the President signed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) into law. Sections 4005 and 4114(b) of the CARES Act authorize the Secretary to require, “to the extent reasonable and practicable,” an air carrier receiving financial assistance under the Act to maintain scheduled air transportation service as the Secretary deems necessary to ensure services to any point served by that air carrier before March 1, 2020. -

AIRMALL USA's Media

GO WITH US CORPORATE OVERVIEW First launched at Pittsburgh International Airport in 1992, the AIRMALL is the gold standard for airport retail in the United States. Featuring a combination of popular international brands and high-quality local favorites, the AIRMALL model generates some of the highest per-passenger spends in the U.S. and regularly earns accolades for innovation and customer service. Travelers GO WITH US, because AIRMALL has developed proven strategies to improve airport concessions, increasing competition and enhancing the passenger experience. A better passenger experience means higher revenue for airports and more economic opportunity for business owners, job seekers and the community at large. AIRMALL USA is owned by Fraport Group, one of the leading groups in the international airport business. With Frankfurt Airport, the company operates one of the world's most important air transportation hubs. 1-800-ITS-FAIR • WWW.AIRMALL.COM • AIRMALL GO WITH THE FACTS CONTACT INFORMATION AIRMALL Boston 300 Terminal C Boston Logan International Airport Founded: 1991 Boston, MA 02128 P: 617-567-8881 • F: 617-567-0885 Number of Employees: 29 AIRMALL Cleveland Cleveland Hopkins International Airport CORPORATE LEADERSHIP Concourse B 5300 Riverside Drive • Kevin Romango – Chief Financial Officer Cleveland, OH 44135 • Jay Kruisselbrink – Senior Vice President P: 216-265-0700 • F: 216-265-1615 • Mike Caro – Vice President, AIRMALL Boston • Tina LaForte – Vice President, AIRMALL Cleveland AIRMALL Maryland • Brett Kelly – Vice President, AIRMALL Maryland P.O. Box 377 • Alan Gluck – Director of Business Development Linthicum, MD 21090 P: 410-859-9201 • F: 410-859-9204 CORE SERVICES AIRMALL Pittsburgh • Retail Property Development Pittsburgh International Airport • Leasing P.O. -

Silicon Valley Bank) 1\ M~Mt>Tr of SVB L'lrw~W Crwp Account Details Requested Date: From: 09/10/2015 To: 10/03/2015 Generated On: 10/15/2015

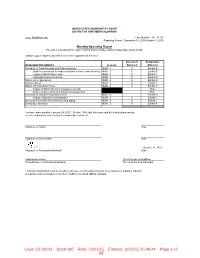

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA In re: NewZoom, Inc. Case Number: 15 - 31141 Reporting Period: September 10, 2015-October 3, 2015 Monthly Operating Report File with Court and submit copy to United States Trustee within 20 days after end of month Submit copy of report to any official committee appointed in the case. Document Explanation REQUIRED DOCUMENTS Form No. Attached Attached Schedule of Cash Receipts and Disbursements MOR - 1 X Exhibit A Bank Reconciliation (or copies of debtor's bank reconciliation's) MOR - 1 X Exhibit B Copies of Bank Statements MOR - 1 X Exhibit C Cash disbursements journal MOR - 1 X Exhibit D Statement of Operations MOR - 2 X Exhibit E Balance Sheet MOR - 3 X Exhibit F Status of Postpetition Taxes MOR - 4 X Exhibit G Copies of IRS Form 6123 or payment receipt None Copies of tax returns filed during reporting period None Summary of Unpaid Postpetition Debts MOR - 4 Exhibit H Listing of aged accounts payable MOR - 4 X Exhibit I Accounts Receivable Reconciliation and Aging MOR - 5 X Exhibit J Debtor Questionnaire MOR - 5 X Exhibit K I declare under penalty of perjury (28 U.S.C. Section 1746) that this report and the attached documents are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. Signature of Debtor Date Signature of Joint Debtor Date October 21, 2015 Signature of Authorized Individual* Date Andrew Hinkelman Chief Restructuring Officer Printed Name of Authorized Individual Title of Authorized Individual * Authorized individual must be an officer, director, or shareholder if debtor is a corporation; a partner if debtor is a partnership; a manager or member if debtor is a limited liability company. -

Fraport’S Recent Investment: a Questionable Platform for U.S

Fraport’s Recent Investment: A Questionable Platform for U.S. Growth AIRMALL USA – An Extensive Review Analyst: Ian Mikusko (212) 332-9330 [email protected] raport AG is a German-based airport owner and operator with its primary operation at FFrankfurt Airport. In August 2014, Fraport acquired airport concessions developer AIR- MALL USA, which currently stands as Fraport’s only investment in the North American mar- ket. Immediately following the acquisition, Fraport announced its intention to use AIRMALL as a platform for developing its U.S. business and to increase its U.S. brand exposure. This report examines whether AIRMALL is a suitable vehicle for growth in the U.S. market. AIRMALL is a concessions developer that is contracted to develop and manage food and retail programs at four U.S. airports. Unlike most companies in Fraport’s portfolio, AIRMALL does not manage entire airports. Rather, it manages airports’ food and retail concessions programs. Another difference is that AIRMALL operates in an airport industry that remains publicly owned. While many European airports have privatized, every airport in the continental United States is governed by state or local governments. AIRMALL is a relatively small company, holding concessions AIRMALL’s ability to win new business leases at just four airports. Fraport has stated its intention to and to maintain its existing accounts grow AIRMALL, thereby increasing Fraport’s own presence is a critical factor in considering and visibility in the market. AIRMALL’s ability to win new the prudence of Fraport’s AIRMALL business and to maintain its existing accounts is a critical factor investment. -

Invitation to Bid Invitation Number 2519H037

INVITATION TO BID INVITATION NUMBER 2519H037 RETURN THIS BID TO THE ISSUING OFFICE AT: Department of Transportation & Public Facilities Statewide Contracting & Procurement P.O. Box 112500 (3132 Channel Drive, Suite 350) Juneau, Alaska 99811-2500 THIS IS NOT AN ORDER DATE ITB ISSUED: January 24, 2019 ITB TITLE: De-icing Chemicals SEALED BIDS MUST BE SUBMITTED TO THE STATEWIDE CONTRACTING AND PROCUREMENT OFFICE AND MUST BE TIME AND DATE STAMPED BY THE PURCHASING SECTION PRIOR TO 2:00 PM (ALASKA TIME) ON FEBRUARY 14, 2019 AT WHICH TIME THEY WILL BE PUBLICLY OPENED. DELIVERY LOCATION: See the “Bid Schedule” DELIVERY DATE: See the “Bid Schedule” F.O.B. POINT: FINAL DESTINATION IMPORTANT NOTICE: If you received this solicitation from the State’s “Online Public Notice” web site, you must register with the Procurement Officer listed on this document to receive subsequent amendments. Failure to contact the Procurement Officer may result in the rejection of your offer. BIDDER'S NOTICE: By signature on this form, the bidder certifies that: (1) the bidder has a valid Alaska business license, or will obtain one prior to award of any contract resulting from this ITB. If the bidder possesses a valid Alaska business license, the license number must be written below or one of the following forms of evidence must be submitted with the bid: • a canceled check for the business license fee; • a copy of the business license application with a receipt date stamp from the State's business license office; • a receipt from the State’s business license office for -

Amazon Air's Summer Surge

Amazon Air’s Summer Surge Strategic Shifts for a Retailing Giant Chaddick Policy Brief by Joseph P. Schwieterman, Jacob Walls and Borja González Morgado September 10, 2020 Our analysis of Amazon Air’s summer operations indicates that the carrier… Added nine planes from May – July, the most it has added over a three-month span in its history Has expanded flight activity 30%+ since April through fleet expansion and improved utilization Adheres to a point-to-point strategy, deemphasizing major huBs even more than last spring Significantly changed service patterns in the Northeast and Florida, creating several mini-hubs Continues to deemphasize international flying while adding lift to Hawaii and Puerto Rico Amazon Air expanded rapidly during summer 2020, a period otherwise marked by sharp year-over-year declines in air-cargo traffic.1 This fully owned subsidiary of retailing giant Amazon made notable moves affecting its strategic trajectory.2 This brief offers an overview of Amazon Air’s evolving orientation between May and late August 2020. The document draws upon publicly available data from a variety of informational sources. Joseph Schwieterman, Ph.D. ñ Data on 1,400 takeoffs and landings of Amazon Air planes from flightaware.com and flightradar24 in April and September 2020. ñ Information on fleet registration from various published sources, including Planespotters.com. ñ Geographic analysis of the proximity of Amazon Air airports to its 340 fulfillment centers. Jacob Walls The results build upon on our May 2020 Brief, showing the dynamic nature of the carrier’s schedules, its differences from air-cargo integrators such as FedEx, its heavy emphasis on cargo-oriented airports with little passenger traffic, and why we believe its fleet could grow to 200 planes by 2028. -

December 2012/January 2013

INTERNATIONAL EDITION DECEMBER/JANUARY 2013 Blazing New Trails December/January 2013 Volume 15, Number 11 EDITOR Jon Ross contents [email protected] • (770) 642-8036 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Keri Forsythe [email protected] • (770) 642-8036 SPECIAL CORRESPONdeNT Martin Roebuck Back Pages March 1958: “What shippers are putting into the air” CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 20 Roger Turney, Ian Putzger CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHER Rob Finlayson Leaders COLUMNIST Blazing new trails Brandon Fried 22 PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Ed Calahan CIRCULATION MaNAGER Advertising Feature Nicola Mitcham Time critical [email protected] 28 ART DIRECTOR CENTRAL COMMUNICATIONS GROUP [email protected] Directory PUBLISHER Airports . 33 Steve Prince Air carriers . 40 [email protected] 33 Air forwarders . 43 ASSISTANT TO PUBLISHER Susan Addy [email protected] • (770) 642-9170 DISPLAY ADVERTISING TRAFFIC COORDINATOR Cindy Fehland [email protected] WORLD NEWS AIR CaRGO WORLD HeadQUARTERS 1080 Holcomb Bridge Rd., Roswell Summit 6 Europe Building 200, Suite 255, Roswell, GA 30076 (770) 642-9170 • Fax: (770) 642-9982 10 Middle East WORLdwIde SaLES U.S. Sales Japan 14 Asia Associate Publisher Masami Shimazaki Pam Latty [email protected] (678) 775-3565 lobe.ne.jp 17 Americas [email protected] +81-42-372-2769 Europe, Thailand United Kingdom, Chower Narula Middle East [email protected] David Collison +66-2-641-26938 +44 192-381-7731 Taiwan [email protected] Ye Chang Hong Kong, [email protected] Malaysia, +886 2-2378-2471 DEPARTMENTS Singapore Australia, Joseph Yap New Zealand +65-6-337-6996 Fergus Maclagan 4 Editorial 61 Bottom Line [email protected] [email protected] 54 5 Questions/People/Events 62 Forwarders’ Forum India +61-2-9460-4560 Faredoon Kuka Korea 58 Classifieds RMA Media Mr. -

Auvsi's Unmanned Systems

AUVSI’S UNMANNED SYSTEMS CONFERENCE IN WASHINGTON, DC In conjunction with the State attendees and 550+ exhibitors able to reconnect with several of Ohio, Wilmington Air Park from more than 40 countries. companies who had previously exhibited at the national The AUVSI Unmanned Systems expressed an interest in the Air Association of Unmanned Vehicle conference is recognized as the Park and made a number of Systems International (AUVSI) leading event for the unmanned connections with new potential annual conference in Washington systems marketplace. tenants.” Representative Turner’s DC on August 12 – 15. The show and Senator Portman’s staff was attended by more than 8,000 Attendees were very impressed visited the booth and they spent with Ohio’s presence at the show. time walking the show floor Ohio hosted a reception on the promoting Ohio’s strength in second day of the conference. unmanned systems. Morley Safer The event was so popular that from 60 Minutes was seen on the visitors filled the booth space and show floor on Tuesday with his overflowed into the aisles. Ohio’s camera crew. Look for a feature booth size, quality, number of on the show in the near future. attendees and booth activity were evidence of the commitment to The main topics at the conference the industry and Ohio’s relevance were FAA Test site designation, in the market. reduced military spending, commercial applications and Wilmington Air Park was privacy issues. These topics are represented by its real estate vital to the Wilmington Air Park’s broker, Jones Lang LaSalle’s continued success as a center of David Lotterer who said, “I was excellence in the UAS industry. -

Office of the Chancellor Records AR-023

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8223145 No online items Office of the Chancellor Records AR-023 Liz Phillips University of California, Davis Library, University Archives 2018 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/archives-and-special-collections Office of the Chancellor Records AR-023 1 AR-023 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis Library, University Archives Title: Office of the Chancellor Records Creator: University of California, Davis. Office of the Chancellor. Identifier/Call Number: AR-023 Physical Description: 489.4 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1937-2014 Abstract: Office files relating to the physical planning and administration of the University of California, Davis. Biography/Administrative History Chancellors who have served the UC Davis campus: Stanley B. Freeborn (1958-1959); Emil M. Mrak (1959-1969); James H. Meyer (1969-1987); Theodore L. Hullar (1987-1994); Larry N. Vanderhoef (1994-2009), Linda P. B. Katehi (2009-2016), and Gary S. May (2017-). Scope and Content of Collection Office files relating to the physical planning and administration of the University of California, Davis. Access Collection is open for research. Preferred Citation Office of the Chancellor Records. UC Davis. University Archives Publication Rights All applicable copyrights for the collection are protected under chapter 17 of the U.S. Copyright Code. Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Regents of the University of California as the owner of the physical items.