Elective Affinity and Crisis: Intellectual Entanglements and Political Divergences in the Weber Circle, 1912–17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loneliness of Human in the Philosophy of Ernst Bloch Culture

SHS Web of Conferences 72, 03002 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf /20197203002 APPSCONF-2 019 Loneliness of human in the philosophy of Ernst Bloch culture Pavel Lyashenko 1, and Maxim Lyashchenko 1 1Orenburg State University, 460018, Orenburg, Russia Abstract. The problem of loneliness from the view point of philosophical and anthropological knowledge acquires special significance, is filled with new content in connection with the unfolding of the modern society transformation processes, as a result, with a new stage in the reappraisal of the modern culture utopian consciousness. At the same time, Ernst Bloch's culture philosophy induce particular scientific interest, according to which the meaningful status of utopia is determined by the fact that it forms a certain ideal image of the human world, which is the space of culture as a whole. In this regard, the study of the loneliness phenomenon in Ernst Bloch culture philosophy allows us to identify the socio-cultural mechanisms of loneliness, as well as key factors in the development of modern society, leading the person to negation and the destruction of his being. 1 Introduction Like a lot of factors that form the everyday world of human, loneliness, culture, utopia belong to the phenomena of human being that are complex for scientific and philosophical comprehension. Turning to the theoretical heritage of the past and modern philosophical research leads to mutually exclusive judgments about loneliness, about culture, and about utopia. Sometimes we come to the idea of the incompatibility of these phenomena, in the absence of any strong and stable connection between them. -

Rickert, Weber, and the Dual Contrast Theory∗

Chapter published in I. Bryan, P. Langford & J. McGarry (eds.), The Foundation of the Juridico-Political: Concept Formation in Hans Kelsen and Max Weber, London, Routledge, 2016, 77-96. PLEASE QUOTE FROM PUBLISHED VERSION ONLY Addressing the Specificity of Social Concepts: Rickert, Weber, and the Dual Contrast Theory∗ Arnaud Dewalque, University of Liège One of the greatest sources of perplexity in Weberian studies centres upon the fact that Max Weber’s epistemological reflexions are located at the intersection between two competing paradigms. On the one side, they are tied to Johannes Von Kries’ theory of ‘objective possibilities’ and causal imputation.1 On the other, they developed under the much-debated influence of Heinrich Rickert’s theory of concept formation in the historical sciences.2 Now, these two paradigms seem initially hardly compatible with each other, since the first one is generally regarded as having a naturalistic orientation while the second is explicitly supported by an anti-naturalistic form of thought. Hence, the fact that Weber’s epistemological reflexions may be properly described as located ‘between Rickert and Von Kries’3 creates a puzzling situation: How are these two competing paradigms supposed to be combined into one single, coherent perspective, as appears to be the case in Weber’s early epistemological or methodological essays? Thus, it is not surprising that one recent, important question for investigation has been whether Weber’s methodology may be considered to have the character a consistent theory, and, if it does, whether such an integrative approach really is capable of illuminating the methodological procedures actually used in the social sciences – or, at least, some relevant aspects thereof. -

Switching Gestalts on Gestalt Psychology: on the Relation Between Science and Philosophy

Switching Gestalts on Gestalt Psychology: On the Relation between Science and Philosophy Jordi Cat Indiana University The distinction between science and philosophy plays a central role in meth- odological, programmatic and institutional debates. Discussions of disciplin- ary identities typically focus on boundaries or else on genealogies, yielding models of demarcation and models of dynamics. Considerations of a disci- pline’s self-image, often based on history, often plays an important role in the values, projects and practices of its members. Recent focus on the dynamics of scientiªc change supplements Kuhnian neat model with a role for philoso- phy and yields a model of the evolution of philosophy of science. This view il- luminates important aspects of science and itself contributes to philosophy of science. This interactive model is general yet based on exclusive attention to physics. In this paper and two sequels, I focus on the human sciences and ar- gue that their role in the history of philosophy of science is just as important and it also involves a close involvement of the history of philosophy. The focus is on Gestalt psychology and it points to some lessons for philosophy of science. But, unlike the discussion of natural sciences, the discussion here brings out more complication than explication, and skews certain kinds of generaliza- tions. 1. How Do Science and Philosophy Relate to Each Other? a) As Nietzsche put it in the Genealogy of Morals: “Only that which has no history can be deªned.” This notion should make us wary of Heideggerian etymology, conceptual analysis and even Michael Friedman’s relativized, dialectical, post-Kuhnian Hegelianism alike. -

Romanist: Im Dienste Der Deutschen Nation Eduard Wechssler

UNIVERSITÉ PAUL VERLAINE METZ UNIVERSITÄT KASSEL Fachbereich Gesellschaftswissenschaften Eduard Wechssler (1869-1949), Romanist: Im Dienste der deutschen Nation Eduard Wechssler (1869-1949), Romaniste : Au service de la nation allemande Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr.phil.) THÈSE DE DOCTORAT préparée en cotutelle par Susanne Dalstein-Paff Sous la direction de: Monsieur le Professeur Michel Grunewald Professor Dr. Hans Manfred Bock Kassel/Metz , Oktober 2006 Datum der Disputation: 15.März 2007 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einführung 6 2. Eduard Wechssler: Zur Person 18 2.1. Schulische Sozialisation 23 2.2. Studium 29 2.3. Universitäre Karriere und Lebensstationen 32 Halle und Marburg 32 Ruf nach Berlin 40 Exkurs: Charakterisierungen 46 Berlin 50 Nachfolge 51 Handelshochschule 55 Nachkriegszeit – Sontheim/Brenz 57 3. Weimarer Republik und „Wesenskunde“ 59 3.1. Der politische Zusammenhang 59 3.2. Der intellektuellengeschichtliche Zusammenhang 66 Die Verantwortung der Intellektuellen 66 Die Intellektuellen und der Weltkrieg 68 Der Intellektuelle und die Politik 72 Der „Erzieher des Volkes“ 75 Ein „Helfer der Nation“ 81 Die Krise der Wissenschaften 83 Positivismus 84 Hochschulen und Bildungsidee 87 Historismus 90 3 Synthese 91 Weltanschauung 92 Wilhelm Dilthey 95 Phänomenologie 99 3. 3. Der bildungspolitische Rahmen: Deutschunterricht, Fremdsprachenunterricht, Realien- und Kulturkunde. 100 Die Konsequenzen der Kultur- und Wesenskunde für den Französischunterricht 124 Die Konsequenzen der Kultur- -

Husserl's Position Between Dilthey and the Windelband-Rickert School of Neo-Kantianism John E

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies Faculty Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies Publications 4-1988 Husserl's Position Between Dilthey and the Windelband-Rickert School of Neo-Kantianism John E. Jalbert Sacred Heart University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/rel_fac Part of the Philosophy of Mind Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Recommended Citation Jalbert, John E. "Husserl's Position Between Dilthey and the Windelband-Rickert School of Neo-Kantianism." Journal of the History of Philosophy 26.2 (1988): 279-296. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +XVVHUO V3RVLWLRQ%HWZHHQ'LOWKH\DQGWKH:LQGHOEDQG5LFNHUW 6FKRRORI1HR.DQWLDQLVP John E. Jalbert Journal of the History of Philosophy, Volume 26, Number 2, April 1988, pp. 279-296 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\7KH-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/hph.1988.0045 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/hph/summary/v026/26.2jalbert.html Access provided by Sacred Heart University (5 Dec 2014 12:35 GMT) Husserl's Position Between Dilthey and the Windelband- Rickert School of Neo- Kanuamsm JOHN E. JALBERT THE CONTROVERSY AND DEBATE over the character of the relationship between the natural and human sciences (Natur- und Geisteswissenschaflen) became a central theme for philosophical reflection largely through the efforts of theo- rists such as Wilhelm Dilthey and the two principal representatives of the Baden School of Neo-Kantians, Wilhelm Windelband and Heinrich Rickert.~ These turn of the century theorists are major figures in this philosophical arena, but they are by no means the only participants in the effort to grapple with this issue. -

The End and the Beginning

The End and the Beginning by Hermynia Zur Mühlen On-line Supplement Edited and translations by Lionel Gossman © 2010 Lionel Gossman Some rights are reserved. This supplement is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Details of allowances and restrictions are available at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com Table of Contents Page I. Feuilletons and fairy tales. A sampling by Hermynia Zur Mühlen (Translations by L. Gossman) Editor’s Note (L. Gossman) 4 1. The Red Redeemer 6 2. Confession 10 3. High Treason 13 4. Death of a Shade 16 5. A Secondary Happiness 22 6. The Señora 26 7. Miss Brington 29 8. We have to tell them 33 9. Painted on Ivory 37 10. The Sparrow 44 11. The Spectacles 58 II. Unsere Töchter die Nazinen (Our Daughters the Nazi Girls). 64 A Synopsis (Prepared by L. Gossman) III. A Recollection of Hermynia Zur Mühlen and Stefan Klein 117 by Sándor Márai, the well-known Hungarian novelist and author of Embers (Translated by L. Gossman) V. “Fairy Tales for Workers’ Children.” Zur Mühlen and the 122 Socialist Fairy Tale (By L. Gossman) VI. Zur Mühlen as Translator of Upton Sinclair (By L. 138 Gossman) Page VII. Image Portfolio (Prepared by L. Gossman) 157 1. Illustrations from Was Peterchens Freunde erzählen. 158 Märchen von Hermynia Zur Mühlen mit Zeichnungen von Georg Grosz (Berlin: Der Malik-Verlag, 1921). -

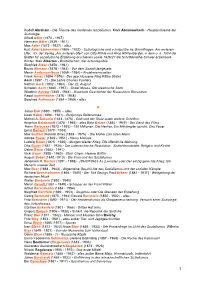

Rudolf Abraham

Rudolf Abraham - Die Theorie des modernen Sozialismus Mark Abramowitsch - Hauptprobleme der Soziologie Alfred Adler (1870 - 1937) Hermann Adler (1839 - 1911) Max Adler (1873 - 1937) - alles Kurt Adler-Löwenstein (1885 - 1932) - Soziologische und schulpolitische Grundfragen, Am anderen Ufer, d.i. der Verlag „Am anderen Ufer“ von Otto Rühle und Alice Rühle-Gerstel, in dem u. a. 1924 die Blätter für sozialistische Erziehung erschienen sowie 1926/27 die Schriftenreihe Schwer erziehbare Kinder Meir Alberton - Birobidschan, die Judenrepublik Siegfried Alkan (1858 - 1941) Bruno Altmann (1878 - 1943) - Vor dem Sozialistengesetz Martin Andersen-Nexø (1869 - 1954) - Proletariernovellen Frank Arnau (1894 -1976) - Der geschlossene Ring Käthe (Kate) Asch (1887 - ?) - Die Lehre Charles Fouriers Nathan Asch (1902 - 1964) - Der 22. August Schalom Asch (1880 - 1957) - Onkel Moses, Der elektrische Stuhl Wladimir Astrow (1885 - 1944) - Illustrierte Geschichte der Russischen Revolution Raoul Auernheimer (1876 - 1948) Siegfried Aufhäuser (1884 - 1969) - alles B Julius Bab (1880 - 1955) – alles Isaak Babel (1894 - 1941) - Budjonnys Reiterarmee Michail A. Bakunin (1814 -1876) - Gott und der Staat sowie weitere Schriften Angelica Balabanoff (1878 - 1965) - alles Béla Balázs (1884 - 1949) - Der Geist des Films Henri Barbusse (1873 - 1935) - 159 Millionen, Die Henker, Ein Mitkämpfer spricht, Das Feuer Ernst Barlach (1870 - 1938) Max Barthel (Konrad Uhle) (1893 - 1975) - Die Mühle zum toten Mann Adolpe Basler (1869 - 1951) - Henry Matisse Ludwig Bauer (1876 - 1935) -

The Limit of Logicism in Epistemology: a Critique of the Marburg and Freiburg Schools” ______

Journal of World Philosophies Articles/1 Translation of Tanabe Hajime’s “The Limit of Logicism in Epistemology: A Critique of the Marburg and Freiburg Schools” _____________________________________ TAKESHI MORISATO Université libre de Bruxelles ([email protected]) This article provides the first English translation of Tanabe’s early essay, “The Limit of Logicism in Epistemology: A Critique of the Marburg and Freiburg Schools” (1914). The key notion that the young Tanabe seeks to define in relation to his detailed analyses of contemporary Neo-Kantian epistemology is the notion of “pure experience” presented in Nishida’s philosophy. The general theory of epistemology shared among the thinkers from these two prominent schools of philosophy in early 20th century Germany aimed to eliminate the empirical residues in Kant’s theory of knowledge while opposing naïve empiricism and the uncritical methodology of positive science. Their “logicistic” approach, according to Tanabe, seems to contradict Nishida’s notion of pure experience, for it cannot allow any vestige of empiricism in its systematic framework, which is specifically designed to ground scientific knowledge. Yet given that the Neo-Kantian configuration of epistemology does not create the object of knowledge, it must face sensation or representational content as its limiting instance. Thus, to ground a Neo-Kantian theory of knowledge while taking account of this limit of logicism involves explaining their understanding of the unity of subject and object in human knowing. For this, -

HISTORY AS the ORGANON of PHILOSOPHY: a LINK BETWEEN the CRITICAL METHOD and the PHILOSOPHY of HISTORY Jacinto Páez

HISTORY AS THE ORGANON OF PHILOSOPHY: A LINK BETWEEN THE CRITICAL METHOD AND THE PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY Jacinto Páez Abstract: In recent years, the Neo-Kantian movement has received wide acknowledgment as the hidden origin of several contemporary philo- sophical discussions. This paper focuses on one specific Neo-Kantian topic; namely, the idea of history put forward by Wilhelm Windelband (1848–1915). Even though this topic could be seen as one of the better- known Neo-Kantianism themes, there are certain unnoticed elements in Windelband’s treatment of history that merit further discussion. While the texts in which Windelband deals with the logical problems of the historical sciences have been studied at length, other texts, those in which history is studied in connection with the problem of the philosophical method, have not. This paper argues that, for Windelband, history is not merely an object of epistemological reflection but rather a key component of transcendental philosophy. Introduction This paper analyzes one aspect of Wilhelm Windelband’s idea of history; namely, the claim that history serves as the proper organon for the system of philosophical knowledge. In addressing this topic I have two goals in mind. On the one hand, I aim to clarify Windelband’s conception of the relationship between philosophical research and historical thinking. On the other hand, I intend to explain how Windelband came to ascribe such a preponderant role to history. By doing so, I will develop a critique of the way in which this Neo-Kantian author is commonly interpreted, and, more importantly, I will set the grounds to assess Windelband’s original contribution to the understanding of the transcendental method. -

Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 7-1-2018 Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Oxford Handbook of the History of Phenomenology (07/18). DOI. © 2018 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft The Oxford Handbook of the History of Phenomenology Edited by Dan Zahavi Print Publication Date: Jun 2018 Subject: Philosophy, Philosophy of Mind, History of Western Philosophy (Post-Classical) Online Publication Date: Jul 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198755340.013.5 Abstract and Keywords This chapter offers a reassessment of the relationship between Kant, the Kantian tradi tion, and phenomenology, here focusing mainly on Husserl and Heidegger. Part of this re assessment concerns those philosophers who, during the lives of Husserl and Heidegger, sought to defend an updated version of Kant’s philosophy, the neo-Kantians. The chapter shows where the phenomenologists were able to benefit from some of the insights on the part of Kant and the neo-Kantians, but also clearly points to the differences. The aim of this chapter is to offer a fair evaluation of the relation of the main phenomenologists to Kant and to what was at the time the most powerful philosophical movement in Europe. Keywords: Immanuel Kant, neo-Kantianism, Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Marburg School of neo-Kantian ism 3.1 Introduction THE relation between phenomenology, Kant, and Kantian philosophizing broadly con strued (historically and systematically), has been a mainstay in phenomenological re search.1 This mutual testing of both philosophies is hardly surprising given phenomenology’s promise to provide a wholly novel type of philosophy. -

Of Ernst Bloch Michael Löwy

C The Principle of Hope from Ernst Bloch is undoubtedly one C R R I of the major works of emancipatory thought in the twentieth century. I Romanticism, Marxism S Monumental (more than 1600 pages), it occupied the author for a large S I I S part of his life.Written during his exile in United States, from 1938 to S 1947, it would be reviewed for the first time in 1953 and a second in & & and Religion in the 1959. Following his condemnation as “revisionist” by authorities of the C C R German Democratic Republic, the author eventually left East Germany R I in 1961. I “Principle of Hope” of T T I Nobody had ever written a book like this, stirring in the same I Q breath the visionary pre-Socratic and Hegelian alchemy, the new Q U U Ernst Bloch E Hoffmann, the serpentine heresy and messianism of Shabbataï Tsevi, E Schelling’s philosophy of art, Marxist materialism, Mozart’s operas V V O and the utopias of Fourier. Open a page at random: it is about the man O L. L. 2 of Renaissance, the concept of (material) substance in Parecelse and 2 Jakob Böhme, of the Holy Family in Marx, of the doctrine of knowledge I I S in Giordano Bruno and the book on the Reform of Knowledge of S S Spinoza. The erudition of Bloch is so encyclopedic that very few readers S Michael Löwy U U E are capable of judging the entirety of each theme developed in the three E #1 volumes of the book. -

The Red Countess Online Supplement IV

The Red Countess Online Supplement IV © 2018 Lionel Gossman Some rights are reserved. This supplement is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Details of allowances and restrictions are available at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com “Fairy Tales for Workers’ Children.” Zur Mühlen and the Socialist Fairy Tale Lionel Gossman Zur Mühlen’s fairy tales were a product both of her responsibility as breadwinner and of her conviction that the writer has a responsibility to open people’s eyes to injustice – the theme of many of her shorter pieces and of various episodes in her longer novels. In the 1920s, as the correspondence with Sinclair shows, this conviction took the form of a commitment to what she herself described as “propaganda” – a word she appears to have understood in its literal sense. In short, it was her duty as a writer to spread the message of socialism, not least among those to whose hardships and humiliations socialism was expected to put an end. In German culture fairy tales occupied a privileged position. They were perceived as the authentic repository of a native culture independent of foreign (classical or French) influence. At the same time, they had a literary pedigree, having moved back and forth between the oral and literary domains, and they continued to be cultivated as a literary genre by nineteenth and twentieth-century writers, from Clemens Brentano and E.T.A Hoffmann to Gerhart Hauptmann, Richard Dehmel, and Hermann Hesse.1 Accordingly, fairy tales were not thought of in the German- speaking countries as intended exclusively for children.