Revolutionary Literature Hunter Bivens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morina on Forner, 'German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics After 1945'

H-German Morina on Forner, 'German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics after 1945' Review published on Monday, April 18, 2016 Sean A. Forner. German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics after 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. xii +383 pp. $125.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-107-04957-4. Reviewed by Christina Morina (Friedrich-Schiller Universität Jena) Published on H-German (April, 2016) Commissioned by Nathan N. Orgill Envisioning Democracy: German Intellectuals and the Quest for Democratic Renewal in Postwar German As historians of twentieth-century Germany continue to explore the causes and consequences of National Socialism, Sean Forner’s book on a group of unlikely affiliates within the intellectual elite of postwar Germany offers a timely and original insight into the history of the prolonged “zero hour.” Tracing the connections and discussions amongst about two dozen opponents of Nazism, Forner explores the contours of a vibrant debate on the democratization, (self-) representation, and reeducation of Germans as envisioned by a handful of restless, self-perceived champions of the “other Germany.” He calls this loosely connected intellectual group a network of “engaged democrats,” a concept which aims to capture the broad “left” political spectrum they represented--from Catholic socialism to Leninist communism--as well as the relative openness and contingent nature of the intellectual exchange over the political “renewal” of Germany during a time when fixed “East” and “West” ideological fault lines were not quite yet in place. Forner enriches the already burgeoning historiography on postwar German democratization and the role of intellectuals with a profoundly integrative analysis of Eastern and Western perspectives. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

P. Skalník Authentic Marx and Anthropology: the Dialectic of Lawrence Krader

P. Skalník Authentic Marx and anthropology: the dialectic of Lawrence Krader In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 136 (1980), no: 1, Leiden, 136-147 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 02:16:55PM via free access REVIEW ARTICLE PETER SKALNfK AUTHENTIC MARX AND ANTHROPOLOGY: THE DIALECTIC OF LAWRENCE KRADER The aim of the present review article is to offer an evaluation of Professor Lawrence Krader's three boks on rhe theory of society and history. At the outset I must say that the books under review l have been written by a man of exceptional learning and erudition. L. Krader undoubtedly has contributed toward a better understanding of the principles of hurnan development. He attempts to set up a landmark with his constructive criticism of both Marx' work and the distortions committed in Marx' name by his foliowers, who have self-appointedly called themselves Marxists. Moreover, Krader seems to claim that his theoretica1 work fits int0 rhe context of the praxis of revolutionary change in the world of today and tomorrow. Before presenting the problems taken up by Krader, I shall try to characterize the background to his study of the Marxian and Marxist stream in social history. L. Krader is a well-known figure among an- thropologists. For many years he was the Secretary-Genera1 of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences. Born in New York on December 8, 1919, he studied first under Alfred Tarski at the City College of New York and later at Yale University. -

GLOBAL HISTORY and NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History

Foreword by Patrick O’Brien Edited by Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa GLOBAL HISTORY AND NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History Series Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Shanghai Jiao Tong University Shanghai, China Lucio De Sousa Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo, Japan This series proposes a new geography of Global History research using Asian and Western sources, welcoming quality research and engag- ing outstanding scholarship from China, Europe and the Americas. Promoting academic excellence and critical intellectual analysis, it offers a rich source of global history research in sub-continental areas of Europe, Asia (notably China, Japan and the Philippines) and the Americas and aims to help understand the divergences and convergences between East and West. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15711 Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa Editors Global History and New Polycentric Approaches Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Lucio De Sousa Shanghai Jiao Tong University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Shanghai, China Fuchu, Tokyo, Japan Pablo de Olavide University Seville, Spain Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History ISBN 978-981-10-4052-8 ISBN 978-981-10-4053-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4053-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937489 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018, corrected publication 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Romanist: Im Dienste Der Deutschen Nation Eduard Wechssler

UNIVERSITÉ PAUL VERLAINE METZ UNIVERSITÄT KASSEL Fachbereich Gesellschaftswissenschaften Eduard Wechssler (1869-1949), Romanist: Im Dienste der deutschen Nation Eduard Wechssler (1869-1949), Romaniste : Au service de la nation allemande Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr.phil.) THÈSE DE DOCTORAT préparée en cotutelle par Susanne Dalstein-Paff Sous la direction de: Monsieur le Professeur Michel Grunewald Professor Dr. Hans Manfred Bock Kassel/Metz , Oktober 2006 Datum der Disputation: 15.März 2007 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einführung 6 2. Eduard Wechssler: Zur Person 18 2.1. Schulische Sozialisation 23 2.2. Studium 29 2.3. Universitäre Karriere und Lebensstationen 32 Halle und Marburg 32 Ruf nach Berlin 40 Exkurs: Charakterisierungen 46 Berlin 50 Nachfolge 51 Handelshochschule 55 Nachkriegszeit – Sontheim/Brenz 57 3. Weimarer Republik und „Wesenskunde“ 59 3.1. Der politische Zusammenhang 59 3.2. Der intellektuellengeschichtliche Zusammenhang 66 Die Verantwortung der Intellektuellen 66 Die Intellektuellen und der Weltkrieg 68 Der Intellektuelle und die Politik 72 Der „Erzieher des Volkes“ 75 Ein „Helfer der Nation“ 81 Die Krise der Wissenschaften 83 Positivismus 84 Hochschulen und Bildungsidee 87 Historismus 90 3 Synthese 91 Weltanschauung 92 Wilhelm Dilthey 95 Phänomenologie 99 3. 3. Der bildungspolitische Rahmen: Deutschunterricht, Fremdsprachenunterricht, Realien- und Kulturkunde. 100 Die Konsequenzen der Kultur- und Wesenskunde für den Französischunterricht 124 Die Konsequenzen der Kultur- -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee -

A Thousand Plateaus and Philosophy

Chapter 13 7000 BC: Apparatus of Capture Daniel W. Smith I Te ‘Apparatus of Capture’ plateau expands and alters the theory of the state presented in the third chapter of Anti-Oedipus, while at the same time providing a fnal overview of the sociopolitical philosophy developed throughout Capitalism and Schizophrenia. It develops a series of challeng- ing theses about the state, the frst and most general of which is a thesis against social evolution: the state did not and could not have evolved out of ‘primitive’ hunter-gatherer societies. Te idea that human societies progressively evolve took on perhaps its best-known form in Lewis Henry Morgan’s 1877 book, Ancient Society; Or: Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization (Morgan 1877; Carneiro 2003), which had a profound infuence on nineteenth-century thinkers, especially Marx and Engels. Although the title of the third chap- ter of Anti-Oedipus – ‘Savages, Barbarians, Civilized Men’ – is derived from Morgan’s book, the universal history developed in Capitalism and Schizophrenia is directed against conceptions of linear (or even multilinear) social evolution. Deleuze and Guattari are not denying social change, but they are arguing that we cannot understand social change unless we see it as taking place within a feld of coexistence. Deleuze and Guattari’s second thesis is a correlate of the frst: if the state does not evolve from other social formations, it is because it creates its own conditions (ATP 446). Deleuze and Guattari’s theory of the state begins with a consideration of the nature of ancient despotic states, such as Egypt or Babylon. -

The East German Writers Union and the Role of Literary Intellectuals In

Writing in Red: The East German Writers Union and the Role of Literary Intellectuals in the German Democratic Republic, 1971-90 Thomas William Goldstein A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Konrad H. Jarausch Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Karen Hagemann Lloyd Kramer ©2010 Thomas William Goldstein ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Thomas William Goldstein Writing in Red The East German Writers Union and the Role of Literary Intellectuals in the German Democratic Republic, 1971-90 (Under the direction of Konrad H. Jarausch) Since its creation in 1950 as a subsidiary of the Cultural League, the East German Writers Union embodied a fundamental tension, one that was never resolved during the course of its forty-year existence. The union served two masters – the state and its members – and as such, often found it difficult fulfilling the expectations of both. In this way, the union was an expression of a basic contradiction in the relationship between writers and the state: the ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED) demanded ideological compliance, yet these writers also claimed to be critical, engaged intellectuals. This dissertation examines how literary intellectuals and SED cultural officials contested and debated the differing and sometimes contradictory functions of the Writers Union and how each utilized it to shape relationships and identities within the literary community and beyond it. The union was a crucial site for constructing a group image for writers, both in terms of external characteristics (values and goals for participation in wider society) and internal characteristics (norms and acceptable behavioral patterns guiding interactions with other union members). -

The End and the Beginning

The End and the Beginning by Hermynia Zur Mühlen On-line Supplement Edited and translations by Lionel Gossman © 2010 Lionel Gossman Some rights are reserved. This supplement is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Details of allowances and restrictions are available at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com Table of Contents Page I. Feuilletons and fairy tales. A sampling by Hermynia Zur Mühlen (Translations by L. Gossman) Editor’s Note (L. Gossman) 4 1. The Red Redeemer 6 2. Confession 10 3. High Treason 13 4. Death of a Shade 16 5. A Secondary Happiness 22 6. The Señora 26 7. Miss Brington 29 8. We have to tell them 33 9. Painted on Ivory 37 10. The Sparrow 44 11. The Spectacles 58 II. Unsere Töchter die Nazinen (Our Daughters the Nazi Girls). 64 A Synopsis (Prepared by L. Gossman) III. A Recollection of Hermynia Zur Mühlen and Stefan Klein 117 by Sándor Márai, the well-known Hungarian novelist and author of Embers (Translated by L. Gossman) V. “Fairy Tales for Workers’ Children.” Zur Mühlen and the 122 Socialist Fairy Tale (By L. Gossman) VI. Zur Mühlen as Translator of Upton Sinclair (By L. 138 Gossman) Page VII. Image Portfolio (Prepared by L. Gossman) 157 1. Illustrations from Was Peterchens Freunde erzählen. 158 Märchen von Hermynia Zur Mühlen mit Zeichnungen von Georg Grosz (Berlin: Der Malik-Verlag, 1921). -

Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1

* pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. These films shed light on the way Ger- many chose to remember its recent past. A body of twenty-five films is analysed. For insight into the understanding and reception of these films at the time, hundreds of film reviews, censorship re- ports and some popular history books are discussed. This is the first rigorous study of these hitherto unacknowledged war films. The chapters are ordered themati- cally: war documentaries, films on the causes of the war, the front life, the war at sea and the home front. Bernadette Kester is a researcher at the Institute of Military History (RNLA) in the Netherlands and teaches at the International School for Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Am- sterdam. She received her PhD in History FilmFilm FrontFront of Society at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. She has regular publications on subjects concerning historical representation. WeimarWeimar Representations of the First World War ISBN 90-5356-597-3 -

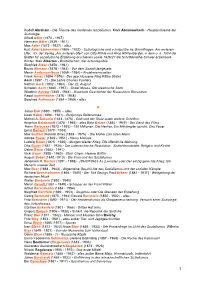

Rudolf Abraham

Rudolf Abraham - Die Theorie des modernen Sozialismus Mark Abramowitsch - Hauptprobleme der Soziologie Alfred Adler (1870 - 1937) Hermann Adler (1839 - 1911) Max Adler (1873 - 1937) - alles Kurt Adler-Löwenstein (1885 - 1932) - Soziologische und schulpolitische Grundfragen, Am anderen Ufer, d.i. der Verlag „Am anderen Ufer“ von Otto Rühle und Alice Rühle-Gerstel, in dem u. a. 1924 die Blätter für sozialistische Erziehung erschienen sowie 1926/27 die Schriftenreihe Schwer erziehbare Kinder Meir Alberton - Birobidschan, die Judenrepublik Siegfried Alkan (1858 - 1941) Bruno Altmann (1878 - 1943) - Vor dem Sozialistengesetz Martin Andersen-Nexø (1869 - 1954) - Proletariernovellen Frank Arnau (1894 -1976) - Der geschlossene Ring Käthe (Kate) Asch (1887 - ?) - Die Lehre Charles Fouriers Nathan Asch (1902 - 1964) - Der 22. August Schalom Asch (1880 - 1957) - Onkel Moses, Der elektrische Stuhl Wladimir Astrow (1885 - 1944) - Illustrierte Geschichte der Russischen Revolution Raoul Auernheimer (1876 - 1948) Siegfried Aufhäuser (1884 - 1969) - alles B Julius Bab (1880 - 1955) – alles Isaak Babel (1894 - 1941) - Budjonnys Reiterarmee Michail A. Bakunin (1814 -1876) - Gott und der Staat sowie weitere Schriften Angelica Balabanoff (1878 - 1965) - alles Béla Balázs (1884 - 1949) - Der Geist des Films Henri Barbusse (1873 - 1935) - 159 Millionen, Die Henker, Ein Mitkämpfer spricht, Das Feuer Ernst Barlach (1870 - 1938) Max Barthel (Konrad Uhle) (1893 - 1975) - Die Mühle zum toten Mann Adolpe Basler (1869 - 1951) - Henry Matisse Ludwig Bauer (1876 - 1935) -

The Hour They Became Human: the Experience of the Working Class In

THE HOUR THEY BECAME HUMAN THE EXPERIENCE OF THE WORKING CLASS IN THE GERMAN REVOLUTION OF NOVEMBER 1918 Nick Goodell University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Department of History Undergraduate Thesis, 2018 The Experience of the Working Class in the German Revolution of November 1918 1 Acknowledgements This project was completed under the supervision of Professor Mark D. Steinberg at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Without his constant devotion, input, and belief in my capability to complete it, this project would simply not exist. For all the untold number of hours of his time through advising both in and outside the office, I owe him a lifetime of thanks. He is one of the many people without whom I would not be the historian I am today. To history department at UIUC, I also owe much for this project. The many professors there I have been lucky enough to either study under or encounter in other ways have had nothing but encouraging words for me and have strengthened my love for history as a field of study. Without the generous grant I was given by the department, I would not have been able to travel to Berlin to obtain the sources that made this project possible. In particular, thanks is owed to Marc Hertzman, director of undergraduate studies, for his direction of the project (and the direction of other undergraduate theses) and his constant willingness to be of assistance to me in any capacity. I also owe great thanks to Professor Diane Koenker, who formerly taught at UIUC, for fostering my early interests in history as a profession and shaping much of my theoretical and methodological considerations of the history of the working class.