The Red Countess Online Supplement IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanist: Im Dienste Der Deutschen Nation Eduard Wechssler

UNIVERSITÉ PAUL VERLAINE METZ UNIVERSITÄT KASSEL Fachbereich Gesellschaftswissenschaften Eduard Wechssler (1869-1949), Romanist: Im Dienste der deutschen Nation Eduard Wechssler (1869-1949), Romaniste : Au service de la nation allemande Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr.phil.) THÈSE DE DOCTORAT préparée en cotutelle par Susanne Dalstein-Paff Sous la direction de: Monsieur le Professeur Michel Grunewald Professor Dr. Hans Manfred Bock Kassel/Metz , Oktober 2006 Datum der Disputation: 15.März 2007 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einführung 6 2. Eduard Wechssler: Zur Person 18 2.1. Schulische Sozialisation 23 2.2. Studium 29 2.3. Universitäre Karriere und Lebensstationen 32 Halle und Marburg 32 Ruf nach Berlin 40 Exkurs: Charakterisierungen 46 Berlin 50 Nachfolge 51 Handelshochschule 55 Nachkriegszeit – Sontheim/Brenz 57 3. Weimarer Republik und „Wesenskunde“ 59 3.1. Der politische Zusammenhang 59 3.2. Der intellektuellengeschichtliche Zusammenhang 66 Die Verantwortung der Intellektuellen 66 Die Intellektuellen und der Weltkrieg 68 Der Intellektuelle und die Politik 72 Der „Erzieher des Volkes“ 75 Ein „Helfer der Nation“ 81 Die Krise der Wissenschaften 83 Positivismus 84 Hochschulen und Bildungsidee 87 Historismus 90 3 Synthese 91 Weltanschauung 92 Wilhelm Dilthey 95 Phänomenologie 99 3. 3. Der bildungspolitische Rahmen: Deutschunterricht, Fremdsprachenunterricht, Realien- und Kulturkunde. 100 Die Konsequenzen der Kultur- und Wesenskunde für den Französischunterricht 124 Die Konsequenzen der Kultur- -

The End and the Beginning

The End and the Beginning by Hermynia Zur Mühlen On-line Supplement Edited and translations by Lionel Gossman © 2010 Lionel Gossman Some rights are reserved. This supplement is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Details of allowances and restrictions are available at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com Table of Contents Page I. Feuilletons and fairy tales. A sampling by Hermynia Zur Mühlen (Translations by L. Gossman) Editor’s Note (L. Gossman) 4 1. The Red Redeemer 6 2. Confession 10 3. High Treason 13 4. Death of a Shade 16 5. A Secondary Happiness 22 6. The Señora 26 7. Miss Brington 29 8. We have to tell them 33 9. Painted on Ivory 37 10. The Sparrow 44 11. The Spectacles 58 II. Unsere Töchter die Nazinen (Our Daughters the Nazi Girls). 64 A Synopsis (Prepared by L. Gossman) III. A Recollection of Hermynia Zur Mühlen and Stefan Klein 117 by Sándor Márai, the well-known Hungarian novelist and author of Embers (Translated by L. Gossman) V. “Fairy Tales for Workers’ Children.” Zur Mühlen and the 122 Socialist Fairy Tale (By L. Gossman) VI. Zur Mühlen as Translator of Upton Sinclair (By L. 138 Gossman) Page VII. Image Portfolio (Prepared by L. Gossman) 157 1. Illustrations from Was Peterchens Freunde erzählen. 158 Märchen von Hermynia Zur Mühlen mit Zeichnungen von Georg Grosz (Berlin: Der Malik-Verlag, 1921). -

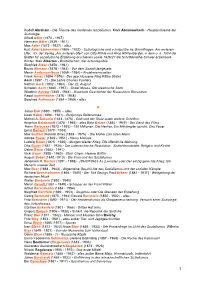

Rudolf Abraham

Rudolf Abraham - Die Theorie des modernen Sozialismus Mark Abramowitsch - Hauptprobleme der Soziologie Alfred Adler (1870 - 1937) Hermann Adler (1839 - 1911) Max Adler (1873 - 1937) - alles Kurt Adler-Löwenstein (1885 - 1932) - Soziologische und schulpolitische Grundfragen, Am anderen Ufer, d.i. der Verlag „Am anderen Ufer“ von Otto Rühle und Alice Rühle-Gerstel, in dem u. a. 1924 die Blätter für sozialistische Erziehung erschienen sowie 1926/27 die Schriftenreihe Schwer erziehbare Kinder Meir Alberton - Birobidschan, die Judenrepublik Siegfried Alkan (1858 - 1941) Bruno Altmann (1878 - 1943) - Vor dem Sozialistengesetz Martin Andersen-Nexø (1869 - 1954) - Proletariernovellen Frank Arnau (1894 -1976) - Der geschlossene Ring Käthe (Kate) Asch (1887 - ?) - Die Lehre Charles Fouriers Nathan Asch (1902 - 1964) - Der 22. August Schalom Asch (1880 - 1957) - Onkel Moses, Der elektrische Stuhl Wladimir Astrow (1885 - 1944) - Illustrierte Geschichte der Russischen Revolution Raoul Auernheimer (1876 - 1948) Siegfried Aufhäuser (1884 - 1969) - alles B Julius Bab (1880 - 1955) – alles Isaak Babel (1894 - 1941) - Budjonnys Reiterarmee Michail A. Bakunin (1814 -1876) - Gott und der Staat sowie weitere Schriften Angelica Balabanoff (1878 - 1965) - alles Béla Balázs (1884 - 1949) - Der Geist des Films Henri Barbusse (1873 - 1935) - 159 Millionen, Die Henker, Ein Mitkämpfer spricht, Das Feuer Ernst Barlach (1870 - 1938) Max Barthel (Konrad Uhle) (1893 - 1975) - Die Mühle zum toten Mann Adolpe Basler (1869 - 1951) - Henry Matisse Ludwig Bauer (1876 - 1935) -

The Hour They Became Human: the Experience of the Working Class In

THE HOUR THEY BECAME HUMAN THE EXPERIENCE OF THE WORKING CLASS IN THE GERMAN REVOLUTION OF NOVEMBER 1918 Nick Goodell University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Department of History Undergraduate Thesis, 2018 The Experience of the Working Class in the German Revolution of November 1918 1 Acknowledgements This project was completed under the supervision of Professor Mark D. Steinberg at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Without his constant devotion, input, and belief in my capability to complete it, this project would simply not exist. For all the untold number of hours of his time through advising both in and outside the office, I owe him a lifetime of thanks. He is one of the many people without whom I would not be the historian I am today. To history department at UIUC, I also owe much for this project. The many professors there I have been lucky enough to either study under or encounter in other ways have had nothing but encouraging words for me and have strengthened my love for history as a field of study. Without the generous grant I was given by the department, I would not have been able to travel to Berlin to obtain the sources that made this project possible. In particular, thanks is owed to Marc Hertzman, director of undergraduate studies, for his direction of the project (and the direction of other undergraduate theses) and his constant willingness to be of assistance to me in any capacity. I also owe great thanks to Professor Diane Koenker, who formerly taught at UIUC, for fostering my early interests in history as a profession and shaping much of my theoretical and methodological considerations of the history of the working class. -

Revolutionary Literature Hunter Bivens

Revisiting German Proletarian- Revolutionary Literature Hunter Bivens The proletarian-revolutionary literature of Germany’s Weimar Republic has had an ambivalent literary historical reception.1 Rüdiger Safranski and Walter Fähnders entry for “proletarian- revolutionary literature” in the influentialHanser’s Social History of German Literature series (1995, p. 174) recognizes the signi- ficance of the movement’s theoretical debates and its opening up of the proletarian milieu to the literary public sphere, but flatly dismisses the literature itself as one that “did not justify such out- lays of reflection and organization.” In the new left movements of the old Federal Republic, the proletarian-revolutionary culture of the Weimar Republic played a complex role as a heritage to be taken up and critiqued. However, the most influential, if not most substantial, West German account of this literature, Michael Rohrwasser’s (1975, p. 10) Saubere Mädel-Starke Genossen [Clean Girls-Strong Comrades], sharply criticizes the corpus and describes the proletarian mass novel as hopelessly masculinist and productivist, a narrative spectacle of the “disavowal of one’s own alienation.” In the former GDR, on the other hand, after having been largely passed over in the 1950s, proletarian-revolutionary literature, rediscovered in the 1960s, was often described as the heroic preparatory works of a socialist national literature that would develop only later in the worker-and-peasants’ state itself, still bearing the infantile disorders of ultra-leftism and proletkult (Klein, 1972).2 This paper offers a revisionist reading of the pro- letarian-revolutionary literature of Germany’s Weimar Republic. How to cite this book chapter: Bivens, H. -

Staging Failure? Berta Lask's Thomas Münzer (1925) And

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1111/glal.12272 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Smale, C. (2020). Staging Failure? Berta Lask's 'Thomas Münzer' (1925) and the 400th Anniversary of the German Peasants' War. German Life and Letters, 73(3), 365-382. https://doi.org/10.1111/glal.12272 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Amalia Blank

Amalia Blank (26.7.1910 – 20.4.2006) Country: Estonia City: Tallinn Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya Date of interview: September 2005 Pictures: Faivi Kljutchik and A. Blank archive. Numbers in brackets refer to the comments that are in the original article on the Centropa site. I think it was a godsend when I met Amalia. This amazing woman has remained young in her soul at the age of 95 after having had many losses in her hard life. She has such a strong spirit, such optimism and soundness of mind that it is hard to believe how old she really is. Amalia is of short height. She is still very feminine, wearing lipstick and a string of pearls around her neck. Her hair is nicely done. She has shiny grey hair and young looking, fair eyes. Amalia knows how to find joy in every moment of her difficult life. Even young people could envy her quick reaction and the vividness of her speech. There are a lot of things to remember. Her life would be interesting to write a novel about. Amalia fulfilled the main purpose of her life. She was born an actress, she knew, what she wanted to be, and achieved it. Her second purpose was to love and to be helpful to her beloved one. Amalia and her husband found each other when they were not young any more, when their lives had been shattered. Probably age does not mean anything in love. They were happy, but not for long. Boris got seriously ill and then Amalia fulfilled her calling. -

Jews in Leipzig: Nationality and Community in the 20 Century

The Dissertation Committee for Robert Allen Willingham II certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Jews in Leipzig: Nationality and Community in the 20 th Century Committee: ______________ David Crew, Supervisor ______________ Judith Coffin ______________ Lothar Mertens ______________ Charters Wynn ______________ Robert Abzug Jews in Leipzig: Nationality and Community in the 20 th Century by Robert Allen Willingham II, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presen ted to the Faculty of the Graduate School the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2005 To Nancy Acknowledgment This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), which provided a year -long dissertation grant. Support was also provided through the History Department at the University of Texas through its Sheffield grant for European studies. The author is also grateful for the assistance of archivists at the Leipzig City Archive, the Archive of the Israelitische Religionsgemieinde zu Leipzig , the Archive for Parties and Mass Organizations in the GDR at the Federal archive in Berlin, the “Centrum Judaica” Archive at the Stiftung Neue Synagoge, also in Berlin, and especially at the Saxon State Archive in Leipzig. Indispensable editorial advice came from the members of the dissertation committee, and especially from Professor David Crew, whose advice and friendship have been central to the work from beginning to end. Any errors are solely those of the author. iv Jews in Leipzig: Nationality and Community in the 20th Century Publication No. _________ Robert Allen Willingham II, PhD. -

Der Argentinische Krösus

jeanette erazo heufelder Der argentinische Krösus Kleine Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Frankfurter Schule BERENBERG Vorwort 7 1898–1930 Ein Reich aus Weizen 12 Vom Kronprinzen zum Vertrauten des Vaters 18 Plötzlich Revolutionär ! 27 Doppelleben in Buenos Aires 33 Der Institutsstifter 39 Im Visier der politischen Polizei 53 Krach mit Moskau 63 Das Mausoleum 69 Das Wesen von Freundschaft 74 Stiller Teilhaber im Malik-Verlag 78 Der Kaufmann von Berlin 84 Panzerkreuzer Potemkin 88 Letzte Tage in Berlin 91 1930–1950 Ende der Getreide-Ära 96 ROBEMA in Rotterdam 100 Zwischen politischen Emigranten und Berufsrevolutionären 108 Auf der Suche nach einer sinnvollen Aufgabe 111 Ausflug in die Realpolitik 117 Ein Zeppelin am Himmel über Buenos Aires 123 Der Erbstreit 125 Eine für alle Beteiligten schauerliche Geschichte 130 Wachsende Abhängigkeiten 139 Die Finanzen 141 Jakobowicz und der polnische Oberst 144 Fietje Kwaak 145 Das New Yorker Institut 148 Das argentinische Rätsel 155 Zum Abschied ein Geschenk 162 1950–1975 Die letzten 25 Jahre 168 Die Memoiren 172 Ein glückliches Leben oder nur Glück gehabt ? 177 Anmerkungen 181 Nachlässe und Archive 196 Bibliografie 197 Dank 204 … aus London, Rotterdam oder Antwerpen kommen Telegramme mit den Notierungen für die Gebietsvertreter von, etwa, Weil Brothers, deren Gewinne über Jahre die Forschungen der Frankfurter Schule finanzierten, die das orthodoxe ökonomische und mechanistische Trugbild von Basis und Überbau zu überwinden trachtete. Sergio Raimondi, Weil Brothers »Seit gestern ist der 16jährige Frank Weil, einziger Sohn von Felix, aus seiner ersten Ehe hier. (…) Er erinnert in vielem an seinen Vater in dessen Jünglingszeit, als ich ihn sehr gern leiden mochte. Leider fehlt das beste, die Leidenschaft für die Enterbten und die Revolution. -

Friedrich Wolf As Communist Movement Rhetor

REDEFINING REALITY: FRIEDRICH WOLF AS COMMUNIST MOVEMENT RHETOR BY C2008 John T. Littlejohn Submitted to the graduate degree program in Germanic Languages and Literatures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________________ Chairperson ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Date Defended:____________________________________ ii The Dissertation Committee for John T. Littlejohn certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REDEFINING REALITY: FRIEDRICH WOLF AS COMMUNIST MOVEMENT RHETOR ____________________________________ Chairperson ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Date approved:____________________________________ iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank many people without whom this dissertation would never have been completed. First among these is Professor Leonie Marx. In her term as my dissertation advisor, Professor Marx has not only provided great insights into the literary and cultural material necessary for the success of this dissertation, but also provided great insight into the dissertation process as a whole. I would also be remiss if I failed to express my appreciation to Mike Putnam. Since 2001, he has been a good colleague, a good and frequent collaborator, -

John Heartfield: Wallpapering the Everyday Life of Leftist

the art institute of chicago yale university press, new haven and london edited by matthew s. witkovsky Avant-Garde Art Avant-Garde Life in Everyday with essays by jared ash, maria gough, jindŘich toman, nancy j. troy, matthew s. witkovsky, early-twentieth-century european modernism early-twentieth-century and andrés mario zervigÓn contents 8 Foreword 10 Acknowledgments 13 Introduction matthew s. witkovsky 29 1. John Heartfield andrés mario zervigÓn 45 2. Gustav Klutsis jared ash 67 3. El Lissitzky maria gough 85 4. Ladislav Sutnar jindŘich toman 99 5. Karel Teige matthew s. witkovsky 117 6. Piet Zwart nancy j. troy 137 Note to the Reader 138 Exhibition Checklist 153 Selected Bibliography 156 Index 160 Photography Credits 29 john heartfield 1 John Heartfield wallpapering the everyday life of leftist germany andrés mario zervigón 30 john heartfield In Germany’s turbulent Weimar Republic, political orientation defined the daily life of average communists and their fellow travelers. Along each step of this quotidian but “revolutionary” existence, the imagery of John Heartfield offered direction. The radical- left citizen, for instance, might rise from bed and begin his or her morning by perusing the ultra- partisan Die rote Fahne (The Red Banner); at one time, Heartfield’s photomontages regularly appeared in this daily newspaper of the German Communist Party (KPD).1 Opening the folded paper to its full length on May 13, 1928, waking communists would have been confronted by the artist’s unequivocal appeal to vote the party’s electoral list. Later in the day, on the way to a KPD- affiliated food cooperative, these citizens would see the identical composition — 5 Finger hat die Hand (The Hand Has Five Fingers) (plate 13) — catapulting from posters plastered throughout urban areas. -

Manu Skrip Te

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eDoc.VifaPol Manuskripte Ulla Plener (Hrsg.) Clara Zetkin in ihrer Zeit Neue Fakten, Erkenntnisse, Wertungen Manuskripte Clara Zetkin in ihrer Zeit in ihrer Clara Zetkin 76 76 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Manuskripte 76 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung ULLA PLENER (HRSG.) Clara Zetkin in ihrer Zeit Neue Fakten, Erkenntnisse, Wertungen Material des Kolloquiums anlässlich ihres 150. Geburtstages am 6. Juli 2007 in Berlin Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin Ich danke Helga Brangsch für ihre umfangreiche Mitarbeit bei der Herstellung des Manuskriptes. Redaktionelle Bemerkung In den vorliegenden Beiträgen folgt die Schreibweise nur teilweise der Rechtschreibreform – sie wurde den Autoren überlassen, Zitate eingeschlossen. Russische Eigennamen werden in der Umschrift nach Steinitz wiedergegeben. Ulla Plener Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Reihe: Manuskripte, 76 ISBN 3-320-02160-3 Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin GmbH 2008 Satz: Marion Schütrumpf Druck und Verarbeitung: Mediaservice GmbH Bärendruck und Werbung Printed in Germany Inhalt ZUM GELEIT 7 GISELA NOTZ: Clara Zetkin und die internationale sozialistische Frauenbewegung 9 SETSU ITO: Clara Zetkin in ihrer Zeit – für eine historisch zutreffende Einschätzung ihrer Frauenemanzipationstheorie 22 CHRISTA UHLIG: Clara Zetkin als Pädagogin 28 CLAUDIA VON GÉLIEU: Die frühe Arbeiterinnenbewegung und Clara Zetkin (1880er/1890er Jahre) 41 SABINE LICHTENBERGER: „Der Vortrag machte auf die ganze Versammlung einen mächtigen Eindruck.“ Zur Rede Clara Zetkins in Wien am 21. April 1908 49 ECKHARD MÜLLER: Clara Zetkin und die Internationale Frauenkonferenz im März 1915 in Bern 54 MIRJAM SACHSE: „Ich erkläre mich schuldig.“ Clara Zetkins Entlassung aus der Redaktion der „Gleichheit“ 1917 72 OTTOKAR LUBAN: Der Einfluss Clara Zetkins auf die Spartakusgruppe 1914-1918 79 HARTMUT HENICKE: Clara Zetkin: „Um Rosa Luxemburgs Stellung zur russischen Revolution“.