For the Tartu Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUMMARY of Marten Huldermann, a Member of a Livonian Fam- ESSAY Ily of Clerics and Merchants, Has Been Recorded Only Because of His Property Problems

SUMMARY of Marten Huldermann, a member of a Livonian fam- ESSAY ily of clerics and merchants, has been recorded only because of his property problems. György Kádár. The lifework of Bartók and Kodály The son of Tallinn merchant Sorgies Huldermann, the in the light of cultural conquests. Examinations in half-brother of the wife of Helmich Fick and the the era of mass culture regarding central- nephew of Tartu bishop Christian Bomhower and Europeanness and related comparative studies. Franciscan Antonius Bomhower, ended up – a minor – One of the most puzzling of the problems of our world, after his father’s death, in the Aizpute Franciscan mon- both from a human and a cultural scholar standpoint, astery. In his complaint to the Tallinn town council we is how humanity, in addition to the results of environ- can read that he was placed in the monastery against mental and air pollution, can cope with the Anglo- his will due to his mother’s and uncle’s influence, and Saxon mass culture which during the last century and his guardians did nothing to prevent this. They also today is attempting to conquer the world, and is as- made no attempt to ensure that Marten would retain piring to supra-national status. the right to a part of his father’s inheritance. What Over many centuries the peoples of Central Europe were the real motives in Marten’s going to, or being have had experiences in attempted cultural conquest. put in the monastery – in this watershed period of late Central Europe is the place where over the centuries Middle Ages piety versus encroaching Reformation battles have been fought, not only with the aid of weap- ideas? How to explain the behavior of his mother, rela- ons, but also with art, culture and cultural policy, over tives and guardians? What internal family relationships mere existence, as well as the unity of people and in- are reflected by this trouble? There are no final an- dividuals. -

Interrogating Performance Histories

Department of Culture and Aesthetics From Local to Global: Interrogating Performance Histories The year 2018 is declared the “European Year of Cultural Heritage”, a gratifying decision for institu- tions and researchers who devote their time to reflecting upon and bringing to life the common traces remaining from European cultures. At the same time, this declaration raises several questions from both overarching and detailed perspectives. Is it reasonable to speak about a common European cul- tural heritage, or is it rather a weaving together of many local and regional cultures? Do patterns exist in the narrative of the ‘European’ dimension, which we recognize also in national histories? Are there some dominant countries, whose cultural heritage has become emblematic of Europe’s history? And finally, in what ways has the view on European history affected the image of global history, and vice versa? There are, of course, no easy and complete answers of these questions, but they cannot be ignored as only rhetorical musings. On the contrary, the research and the historical writing about local, regional, national, European, and global circumstances are closely interrelated. The histories of performing arts, as they are portrayed from different geographical perspectives, make an excellent example of how spatial and time-related phenomena re-appear in overarching narrative patterns as well as in singular turning points. Europe often acts as the primary gauge in these kinds of histories. The coarse periodization of Ancient Times, the Middle Ages and Modern Time, is still ruling how different performance arts become described in history. Antiquity is the embracing concept used in southern Europe, whereas in the north the label ‘pre-history’ is used. -

Eesti Vasakharitlased Üle Läve: Nähtus, Uurimisseis, Küsimused

Eesti vasakharitlased üle läve: nähtus, uurimisseis, küsimused Nähtus Pärast Eesti okupeerimist Moskva poolt võimule pandud Johannes Vares-Barbaruse valitsuse liikmete seas ei olnud vanglas karastatud vanu põrandaaluseid kommuniste. Õieti polnud seal parteipiletiga kommuniste esialgu üldse. Varese valitsust on asjakohaselt nimetatud hoopis „kirjanduslikku” tüüpi või rahva seas ka kirjanike valitsuseks.1 Tõsi, ka „valitsuse“ nimetus on ilmne eksitus, sest see asutus ei valitsenud, vaid vahendas Moskvas tehtud otsuseid. Pärisvõimu silmis oli sel ebavalitsusel nii vähe autoriteeti, et ka liikme staatus ei kaitsnud repressioonide eest. Poolteist aastat peale ministriks nimetamist oli peaaegu viiendik Varese valitsusest - Boris Sepp, Juhan Nihtig-Narma ja Maksim Unt tapetud sellesama võimu poolt, keda nad sarnaselt suurema osa teistegi ministriteks kutsutud ametimeestega juba enne 1940. aasta juunit olid teenida püüdnud. 2 Selle valitsuse üheteistkümnest mittevalitsevast ministrist olid peaminister Johannes Vares- Barbarus ja haridusminister Johannes Semper kirjanikud, välisminister Nigol Andresen luuletaja, kirjanduskriitik ja tõlkija, peaministri asetäitja Hans Kruus ajalooprofessor. Tegemist ei olnud kõrvaliste boheemlastega, vaid nad olid olnud selles ühiskonnas, mida nad nüüd hävitama asusid, tuntud ja respekteeritud isikud. Vares-Barbaruse 50 eluaasta täitumise puhul tunnustas Eesti Vabariigi ekspeaminister Kaarel Eenpalu teda artiklis „Johannes Barbarus astub üle läve“, parafraseerides Vares-Barbaruse eelmisel aastal ilmunud luulekogu -

Digital Culture As Part of Estonian Cultural Space in 2004-2014

Digital culture as part of Estonian cultural space in 4.6 2004-2014: current state and forecasts MARIN LAAK, PIRET VIIRES Introduction igital culture is associated with the move of Es- in a myriad of implications for culture: we now speak tonia from a transition society to a network so- of such things as levelling, dispersal, hypertextuality, D ciety where “digital communication is bandwidth, anarchy and synchronicity (see Lister 2003: ubiquitous in all aspects of life” (Lauristin 2012: 40). This 13–37; Caldwell 2000: 7–8; Livingstone 2003: 212). Dis- sub-chapter will trace some trends in the development persal is the fragmentation of the production and con- of digital culture in the last decade (2004–2014), with sumption of texts, which in turn is linked to the the objective of examining the intersection of the habits decentralisation and individualisation of culture. On the and needs of users who have adapted to the digital era, other hand, dispersal is linked to the hypertextuality and the possibilities of the network society. Modern and interactivity of new texts circulating in digital en- digital culture also encompasses e-books – an evolution vironments. The digital environment has abolished the that has brought about and aggravated a number of is- traditional centre-periphery cultural model: the inter- sues specific to the development of digital culture. Both relations between texts are non-hierarchical and the e-books and digital culture are strongly linked with the core and periphery of culture are indistinguishable from forecasts concerning the future of education and cul- each other. Texts can be developed as a network in tural creation in Estonia. -

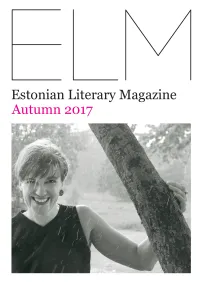

Estonian Literary Magazine · Autumn 2017 · Photo by Kalju Suur Kalju by Maimu Berg · Photo

Contents 2 A women’s self-esteem booster by Aita Kivi 6 Tallinn University’s new “Estonian Studies” master´s program by Piret Viires 8 The pain treshold. An interview with the author Maarja Kangro by Tiina Kirss 14 The Glass Child by Maarja Kangro 18 “Here I am now!” An interview with Vladislav Koržets by Jürgen Rooste 26 The signs of something going right. An interview with Adam Cullen 30 Siuru in the winds of freedom by Elle-Mari Talivee 34 Fear and loathing in little villages by Mari Klein 38 Being led by literature. An interview with Job Lisman 41 2016 Estonian Literary Awards by Piret Viires 44 Book reviews by Peeter Helme and Jürgen Rooste A women’s self-esteem booster by Aita Kivi The Estonian writer and politician Maimu Berg (71) mesmerizes readers with her audacity in directly addressing some topics that are even seen as taboo. As soon as Maimu entered the Estonian (Ma armastasin venelast, 1994), which literary scene at the age of 42 with her dual has been translated into five languages. novel Writers. Standing Lone on the Hill Complex human relationships and the (Kirjutajad. Seisab üksi mäe peal, 1987), topic of homeland are central in her mod- her writing felt exceptionally refreshing and ernist novel Away (Ära, 1999). She has somehow foreign. Reading the short stories also psychoanalytically portrayed women’s and literary fairy tales in her prose collection fears and desires in her prose collections I, Bygones (On läinud, 1991), it was clear – this Fashion Journalist (Mina, moeajakirjanik, author can capably flirt with open-minded- 1996) and Forgotten People (Unustatud ness! It was rare among Estonian authors at inimesed, 2007). -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2016 XXII (49)

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEAR BOOK ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXII (49) 2016 TA LLINN 2017 Editor in chief: Jaak Järv Editor: Anne Pöitel Translation: Ülle Rebo, Ants Pihlak Editorial team: Helle-Liis Help, Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama Maquette: Kaspar Ehlvest Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Reti Kokk: pp. 57, 58; Maris Krünvald: p. 77; Hanna Odras: pp. 74, 78, 80; Anni Õnneleid/Ekspress Meedia: pp. 75, 76; photograph collection of the Estonian Academy of Sciences. Thanks to all authors for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Madis Arukask, Toomas Asser, Arvi Freiberg, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Jelena Kallas, Maarja Kalmet, Tarmo Kiik, Meelis Kitsing, Andres Kollist, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Ants Kurg, Maarja Kõiv, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Marju Luts-Sootak, Olga Mazina, Andres Metspalu, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Ivar Ojaste, Anne Ostrak, Killu Paldrok, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Pille Runnel, Tarmo Soomere, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Jaan Undusk, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar, Richard Villems. Printed in Printing House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA CONTENTS FOREWORD ......................................................................................................... 5 CHRONICLE 2016 ................................................................................................ 8 MEMBERSHIP OF THE ACADEMY ..............................................................19 -

The History of Exile Estonian Literature and Literary Archives Rutt Hinrikus Estonian Literary Museum

The History of Exile Estonian Literature and Literary Archives Rutt Hinrikus Estonian Literary Museum In January 2009, a rather voluminous piece of literary history spanning 800 pages was presented in Tallinn – “Estonian Literature in Exile in the 20th Century”.1 The first 250 pages of this book provide an overview of the prose, followed by overviews of memoirs, drama, poetry, children’s literature and literature in translation. At the end there are overviews of reprints, literary criticism and literary studies. Parts of the book are reprints – all chapters except the most voluminous one on prose have previously been published as fascicles since 1993.2 The publication of this book denotes the reception of Estonian émigré literature on metalevel and provides the reader with interpretations and explanations. The length of the journey which separated émigré literature from disavowal and led to a joint restoration of Estonian literature is illustrated by two recollections. It was 1982 when the head of the Estonian Society for the Development of Friendly Ties Abroad (Välismaaga Sõprussidemete Arendamise Eesti Ühing) asked me if literature which was written in Estonian in Sweden or elsewhere, is Estonian literature. I stuttered my response – in this culturally clean “lawful space” of Soviet state security I felt a bit like a mouse being tossed around by a cat – that at least the work of authors whose creative work began in Estonia was Estonian literature. I wasn’t being questioned, I was being tested. I asked myself where the literature belonged, which was written by authors whose creative work began abroad. I had always thought of it as Estonian émigré literature, meaning, not as pieces of literary creation but more as forbidden fruit resembling the golden apples which grew on strange trees in 1 Kruuspere, Piret (toim) Eesti kirjandus paguluses XX sajandil. -

Development of the Estonian Cultural Space

188 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ESTONIAN 4 CULTURAL SPACE [ ESTONIAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2014/2015 ] INTRODUCTION ! MARJU LAURISTIN he Estonian National Strategy on Sustainable De- ical figures, historical anniversaries and calendars, etc. velopment – Sustainable Estonia 21 (SE21), (Strategy Sustainable Estonia 21). T adopted by the Parliament in 2005, defines sus- To have the viability of the cultural space as a goal tainable development as balanced movement towards and, what is more, as the ultimate development goal is four related objectives: growth of welfare, social coher- unique to the Estonian National Strategy on Sustain- ence, viability (sustainability) of the Estonian cultural able Development. The indicators used by Statistics Es- space and ecological balance (Oras 2012: 45–46). This tonia to illustrate this field include population dynamics chapter explores the ways in which the developments (survival of the Estonian people), use of the Estonian of the last decade have afected the sustainability of the language, and cultural participation (Statistics Estonia Estonian cultural space. The Estonian cultural space as 2009: 12–25). Statistics Estonia is regularly collecting data such is difcult to define scientifically. It is rather a from cultural institutions on the attendance of Estoni- metaphor for the goal stated in the preamble to the ans at cultural venues or events: theatres, museums, li- Constitution: “to ensure the preservation of the Eston- braries, cinemas and museums. Comparative data on ian nation, language and culture through the ages”. SE21 other EU member states are available from Eurobarom- interprets a cultural space as an arrangement of social eter surveys undertaken in 2007 and 2013. These data life which is carried by people identifing themselves as can be used to determine how the use of Estonian, at- Estonians and communicating in Estonian. -

The Curving Mirror of Time Approaches to Culture Theory Series Volume 2

The Curving Mirror of Time Approaches to Culture Theory Series Volume 2 Series editors Kalevi Kull Institute of Philosophy and Semiotics, University of Tartu, Estonia Valter Lang Institute of History and Archaeology, University of Tartu, Estonia Tiina Peil Institute of History, Tallinn University, Estonia Aims & scope TheApproaches to Culture Theory book series focuses on various aspects of analy- sis, modelling, and theoretical understanding of culture. Culture theory as a set of complementary theories is seen to include and combine the approaches of different sciences, among them semiotics of culture, archaeology, environmental history, ethnology, cultural ecology, cultural and social anthropology, human geography, sociology and the psychology of culture, folklore, media and com- munication studies. The Curving Mirror of Time Edited by Halliki Harro-Loit and Katrin Kello Both this research and this book have been financed by target-financed project SF0180002s07 and the Centre of Excellence in Cultural Theory (CECT, European Regional Development Fund). Managing editors: Anu Kannike, Monika Tasa Language editor: Daniel Edward Allen Design and layout: Roosmarii Kurvits Cover layout: Kalle Paalits Copyright: University of Tartu, authors, 2013 Photograps used in cover design: Postimees 1946, 1 January, 1 (from the collection of the Estonian Literary Museum Archival Library); Postimees 2013, 2 January, 1 (copyright AS Postimees) ISSN 2228-060X (print) ISBN 978-9949-32-258-9 (print) ISSN 2228-4117 (online) ISBN 978-9949-32-259-6 (online) University of Tartu Press www.tyk.ee/act Contents List of figures ................................................. 7 Notes on editors and contributors ................................ 9 Introduction ................................................. 11 Halliki Harro-Loit Temporality and commemoration in Estonian dailies ................. 17 Halliki Harro-Loit, Anu Pallas Divided memory and its reflection in Russian minority media in Estonia in 1994 and 2009 ............................................ -

Keelta Kirjand Us Sisukord

2. ISSN 0131 1441 igSg KEELTA KIRJAND US SISUKORD В. Kangro. Hiliskohtumisi ühe varase luuletutvusega . 65 H. Keem. Artur Adsoni elust ja loomingust ... 70 J. Kronberg. Artur Adson kodupaigalaulikuna ... 82 T. Help. GLOW '88 Budapestis. Tänapäeva generatiiv- lingvistikast ühe ürituse tausta! (Järg) 87 M. Hiiemäe. Vähetuntut veebruarikuu rahvakalendris . 94 L.-A. Sinijärv. Välismaine eesti perioodika ENSV Tea duste Akadeemia Teaduslikus Raamatukogus ... 97 «Keele ja Kirjanduse» ringküsitlus kirjanikele KOLLEEG I'M: (L. Vaher) 105 P. Ariste, Л. Hint, E Jansen, О Jogi, А Kask, MISTSELLE R. Kull, V Pall, R. Parve. 1. Peep, P. Nurmekund. Mis on tuulekoer ja maasulane? (Ise E. Päll, E. Sõgel, küsin — ise vastan) 107 Л. Ü. Tedre, А. Vinkel. K. Ross. Tahaks siiski keelata 107 PUBLIKATSIOONE TOIMETUS: A. Eelmäe (komment.). A. Adsoni ja F. Tuglase kir A. Tamm (peatoime.aja), javahetus T. Tasa (reitcimetaja asetäitja, k.ijandusteooria ia -kriitika RAAMATUID osakonna toimetaja), Ü. Kahusk. Vist teab sedasama tunnet . И 8 E. Ross (vastutav sekretär), A. Oja. Kas vana arm ka roostetab? 119 P. Lias. Eestluse elujõust 120 H. Niit (kirjandusajaloo ja rahva R. Kruus. Leningradi etnograafide minoriteedihuvi ei luule osakonna toimetaja), rauge 121 U. Uibo E. Vääri. Väitekiri superlatiivi alalt 123 (keeleteaduse osakonna toimetaja), I. Pärnapuu RINGVAADE (toimetaja), O. Kuningas. Noorte hinge külvatud seeme ei kao . 124 R. Karelson. Leksikograafia suurfoorumil Budapestis . 125 Toimetuse aadress: E. Kalmre, K. Tamkivi, K. Peebo. ES-i rahvaluule 200 106 Tallinn, Lauristini 6 Telefonid 449-228, 449-126. sektsioonis 127 L. Aarina. Raamat ja lugeja 128 Laduda antud 18. XII 1988. Trükkida antud 27. I 1989. Trükiarv 3700. Sõktõvkari Paberi Kaanel: Konrad Mägi. -

79114069.Pdf

TARTU ÜLIKOOL Arne Merilai EESTI BALLAAD 1900-1940 Tartu 1991 Kinnitatud filoloogiateaduskonna nõukogus 20. veerbruaril 1991. a. Kaane kujundanud A. Peegel. Арне Мери лай. ЭСТОНСКАЯ БАЛЛАДА 1900-1940. На эстонском языке. Тартуский университет. ЭР, 202 400, г. Тарту, ул. Юлшсооли, 18. Vastutav toimetaja К. Muru. PaJjundamisele antud 25.03.1991. Formaat 60x90/16. Kirjutuspaber. Kiri: roman. Rotaprint. Tingtrükipoognaid 8,37. Arvestuspoognaid 9,86. Trükipoognaid 9,0. Trükiarv 1000. Tell. nr. 135. Hind rbl. 5. TÜ trükikoda. EV, 202 400 Tartu, Tiigi t. 78. © Tartu Ülikool, 1991 SAATEKS Žanride uurimine on kirjandusteaduse tähtsamaid ülesandeid. 193S. aastal valmis Bernard Kangrol Tartu Ülikoolis magistritöö "Eesti soneti ajalugu", katkestada tuli aga doktoritöö eesti romaanist. Hiljem on eesti kirjandusteaduses süvenetud lüürika arengukäiku, uuritud on eepika žanre ja dramaatikatki; Silvia Nagelmaa väitekiri sõjajärgsest eesti- poeemist oli esimeseks katseks vaadelda kirjandust sünteetilise lüroeepika seisukohast. Lüroeepika teine oluline vorm — ballaad — oli aga seni avamata hoolimata rohkest viljeldavusest. Eesti ballaadi areng jaguneb selgesti kolme peamisse ajajärku: ettevalmistav etapp kuni XX sajandu alguseni, XX sajandi esimese poole esteetiline kõrgperiood ja kaasaja ballaad, mida iseloomustab pigem lüüriline kui lüroeepiline suhe žanrisse. Vaid üksikud auto rid hoiavad tänapäeval alles kindlama eepilise lõime. On ilmne, et žanri tähtsuse eesti luules selgitab uurimus keskmise perioodi kohta, millest lähtudes saab teha järeldusi ajas -

SIURU 100 Siuru-Ühing 1917

SIURU 100 Siuru-ühing 1917. Eesti Teaduste Akadeemia Underi ja Tuglase Kirjanduskeskuse ASTRA projekt Under Tuglas Literature Centre of the Estonian Academy of Sciences ASTRA project Euroopa Liit Eesti Euroopa tuleviku heaks Regionaalarengu Fond Konverents SIURU 100 17.–18. mai 2017 Underi ja Tuglase Kirjanduskeskus Eesti Kirjanike Liit Tõlkinud Piret Merimaa, Ene-Reet Soovik ja Adam Cullen TEESID Toimetanud Elle-Mari Talivee, Ene-Reet Soovik ja Kri Marie Vaik Kujundanud Tiiu Pirsko Kasutatud teoseid Underi ja Tuglase Kirjanduskeskuse F. Tuglase kogust ja Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Eesti Kultuuriloolisest Arhiivist Autoriõigused: Eesti TA Underi ja Tuglase Kirjanduskeskus Eesti Kirjanike Liit Tekstid: autorid ISBN 978-9985-865-49-1 Tallinn 2017 SIURU 100 2 3 SIURU 100 4 Illustratsioon: Ado Vabbe 5 KAVA / PROGRAM Kolmapäev/Wednesday, 17. mai/May 17th Neljapäev/Thursday, 18. mai/May 18th 10.30–10.45 Avasõnad: JAAN UNDUSK, TIIT ALEKSEJEV 10.00–10.30 MART VELSKER Artur Adson, Henrik Visnapuu ja 10.45–1 1 . 1 5 AGO PAJUR Tallinn poliitilises keerises 1917–1918 lõunaeestikeelne kirjandus 11.15–11.45 LOLA ANNABEL KASS Esteetiline mõte Euroopas 10.30–11.00 MERLIN KIRIKAL „Inimkonna kõrgeimad õied”: esimese ilmasõja ajal kunstnikukujust Johannes Semperi novellikogus „Hiina kett” ja August Gailiti romaanis „Muinasmaa” 1 1 .45–12.15 MAARJA VAINO Meeletu vabadus. A. H. Tammsaare mõtetest ajavahemikus 1917–1919 11.00–11.30 SIRJE KIIN Tuglase rollid Underi luules 12.15–12.30 Kohvipaus 11.30–11.45 Kohvipaus 12.30–13.00 SILJA VUORIKURU Finnish literature between 11.45–12.15 ANNELI KÕVAMEES Siuru tundmatud kaasteelised 1917 and 1919 12.15–12.45 REIN VEIDEMANN Pulbitsev sõna.