Sanctions, Censure and Punitive Censorship: Some Targeted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The exact Hebrew name for this affair is the “Yemenite children Affair.” I use the word babies instead of children since at least two thirds of the kidnapped were in fact infants. 2. 1,053 complaints were submitted to all three commissions combined (1033 complaints of disappearances from camps and hospitals in Israel, and 20 from camp Hashed in Yemen). Rabbi Meshulam’s organization claimed to have information about 1,700 babies kidnapped prior to 1952 (450 of them from other Mizrahi ethnic groups) and about 4,500 babies kidnapped prior to 1956. These figures were neither discredited nor vali- dated by the last commission (Shoshi Zaid, The Child is Gone [Jerusalem: Geffen Books, 2001], 19–22). 3. During the immigrants’ stay in transit and absorption camps, the babies were taken to stone structures called baby houses. Mothers were allowed entry only a few times each day to nurse their babies. 4. See, for instance, the testimony of Naomi Gavra in Tzipi Talmor’s film Down a One Way Road (1997) and the testimony of Shoshana Farhi on the show Uvda (1996). 5. The transit camp Hashed in Yemen housed most of the immigrants before the flight to Israel. 6. This story is based on my interview with the Ovadiya family for a story I wrote for the newspaper Shishi in 1994 and a subsequent interview for the show Uvda in 1996. I should also note that this story as well as my aunt’s story does not represent the typical kidnapping scenario. 7. The Hebrew term “Sephardic” means “from Spain.” 8. -

“Schlaglicht Israel”!

Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 15/18 Aktuelles aus israelischen Tageszeitungen 1.-31. August Die Themen dieser Ausgabe 1. Weiter Protest gegen Nationalstaatsgesetz ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Zwischen Krieg und Waffenstillstand ............................................................................................................................. 3 3. Abschied von Uri Avnery ................................................................................................................................................. 6 4. Medienquerschnitt ............................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Weiter Protest gegen Nationalstaatsgesetz setz zu annullieren. Die Klageführer_innen mei- Der Streit um das Nationalstaatsgesetz ließ nen, dass das neue Gesetz „das Recht auf Israels Abgeordneten trotz Sommerpause der Gleichheit und das Recht auf Würde“ verletze. Knesset keine Ruhe. Im Verlauf der außeror- Justizministerin Ayalet Shaked kommentierte, dentlichen Debatte um das drei Wochen zuvor dass es ein „Erdbeben“ geben werde, wenn die verabschiedete Grundgesetz „Israel – National- Richter gegen das Nationalstaatsgesetz ent- staat des jüdischen Volkes“ schimpfte Oppositi- scheiden. onschefin Zipi Livni vom Zionistischen Lager auf Regierungschef Benjamin Netanyahu, dessen The best answer to post-Zionism Regierung „Hass und Angst“ verbreite. Für den (...) -

Iraqi Jews: a History of Mass Exodus by Abbas Shiblak, Saqi, 2005, 215 Pp

Iraqi Jews: A History of Mass Exodus by Abbas Shiblak, Saqi, 2005, 215 pp. Rayyan Al-Shawaf The 2003 toppling of Saddam Hussein’s Baath regime and the occupation of Iraq by Allied Coalition Forces has served to generate a good deal of interest in Iraqi history. As a result, in 2005 Saqi reissued Abbas Shiblak’s 1986 study The Lure of Zion: The Case of the Iraqi Jews. The revised edition, which includes a preface by Iraq historian Peter Sluglett as well as minor additions and modifications by the author, is entitled The Iraqi Jews: A History of Mass Exodus. Shiblak’s book, which deals with the mass immigration of Iraqi Jews to Israel in 1950-51, is important both as one of the few academic studies of the subject as well as a reminder of a time when Jews were an integral part of Iraq and other Arab countries. The other significant study of this subject is Moshe Gat’s The Jewish Exodus from Iraq, 1948-1951, which was published in 1997. A shorter encapsulation of Gat’s argument can be found in his 2000 Israel Affairs article Between‘ Terror and Emigration: The Case of Iraqi Jewry.’ Because of the diametrically opposed conclusions arrived at by the authors, it is useful to compare and contrast their accounts. In fact, Gat explicitly refuted many of Shiblak’s assertions as early as 1987, in his Immigrants and Minorities review of Shiblak’s The Lure of Zion. It is unclear why Shiblak has very conspicuously chosen to ignore Gat’s criticisms and his pointing out of errors in the initial version of the book. -

Israel in the Occupied Territories Since 1967

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 The Last Colonialist: Israel in the Occupied Territories since 1967 ✦ RAFAEL REUVENY ith almost prophetic accuracy, Naguib Azoury, a Maronite Ottoman bu- reaucrat turned Arab patriot, wrote in 1905: “Two important phenom- W ena, of the same nature but opposed . are emerging at this moment in Asiatic Turkey. They are the awakening of the Arab nation and the latent effort of the Jews to reconstitute on a very large scale the ancient kingdom of Israel. -

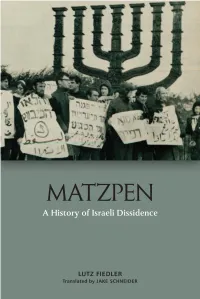

9781474451185 Matzpen Intro

MATZPEN A History of Israeli Dissidence Lutz Fiedler Translated by Jake Schneider 66642_Fiedler.indd642_Fiedler.indd i 331/03/211/03/21 44:35:35 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com Original version © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, 2017 English translation © Jake Schneider, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd Th e Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5116 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5118 5 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5119 2 (epub) Th e right of Lutz Fiedler to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Originally published in German as Matzpen. Eine andere israelische Geschichte (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017) Th e translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Th yssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Offi ce, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association). -

The Arabs in Israel 1948-1966

THE INSTITUTE FOR PALESTINE STUDIES The Institute for Palestine Studies is an independent non-profit Arab research organization not ajfiliated to any government> political party, or group, devoted to a better understanding of the Palestine problem. Books in the Institute series are pub¬ lished in the interest ofpublic information. They represent the free expression of their authors and do not necessarily indicate the judgement or opinions of the Institute. FOUNDERS AND BOARD OF TRUSTEES His Excellency, Mr. Charles Helou Prof. Said Himadeh Now President of the Republic of Lebanon Professor Emeritus, American University of Beirut Mr. Sami Alami Dr. Nejla Tzzeddin General Manager, Arab Bank Ltd., Beirut Authoress and Educator, Beirut Mr. Ahmad Baha-Ed-Din Mr. Adib Jadir President, Press Association Engineer, Baghdad of the U.A.R., Cairo Mr. Abdul Mohsin Kattan Businessman (Kuwait) Mrs. Wad ad Cortas Principal, Ahliya College, Beirut Prof. Walid Khalidi Professor of Political Studies, Prof. Burhan Dajani American University of Beirut Secre tary - General, Dr. Hicham Nachabeh Union of Arab Chambers of Commerce, Director of Education, Industry and Agriculture, Beirut Makassed Association, Beirut Mr. Pierre Edde Dr. Edmond Rabbath Ex-Minister of Finance (Lebanon) Lawyer and Professor of Constitutional Law, Lebanese University Dr. Nabih A. Faris * Mr. Farid Saad Professor of History, Former Senator (Jordan), American University of Beirut Industrialist and businessman Dr. Fuad Sarrouf Mr. Maurice Gemayel Vice-President, Member of Parliament (Lebanon) American University of Beirut Mr. Abdul Latif Hamad Dr. Constantine Zurayk President, Kuwait Fund Distinguished Professor, for Arab Economic Development American University of Beirut * Deceased. THE ARABS IN ISRAEL 1948-1966 (g) Copyright 1968, The Institute for Palestine Studies First impression, 1968 Second impression, 1969 MONOGRAPH SERIES N° 16 THE INSTITUTE FOR PALESTINE STUDIES Ashqar Bldg., Clemenceau Str. -

IMAGINING INDEPENDENCE PARK by Oren Segal a Dissertation

IMAGINING INDEPENDENCE PARK by Oren Segal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) In the University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Shachar M Pinsker, Chair Professor David M. Halperin Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein Assistant Professor Maya Barzilai “Doing it in the park, Doing it after Dark, oh, yeah” The Blackbyrds, “Rock Creek Park,” City Life (Fantasy Records, 1975) © Oren Segal All rights reserved 2012 In memory of Nir Katz and Liz Troubishi ii Acknowledgements Most of all, I would like to thank my committee members: Shachar Pinsker, David Halperin, Carol Bardenstein, and Maya Barzilai. They are more than teachers to me, but mentors whose kindness and wisdom will guide me wherever I go. I feel fortunate to have them in my life. I would also like to thank other professors, members of the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan, who were and are part of my academic and personal live: Anita Norich, Deborah Dash Moore, Julian Levinson, Mikhail Krutikov, and Ruth Tsoffar. I also wish to thank my friends and graduate student colleagues who took part in the Frankel Center’s Reading Group: David Schlitt, Ronit Stahl, Nicholas Block, Daniel Mintz, Jessica Evans, Sonia Isard, Katie Rosenblatt, and especially Benjamin Pollack. I am grateful for funding received from the Frankel Center throughout my six years in Ann Arbor; without the center’s support, this study would have not been possible. I would also like to thank the center’s staff for their help. -

The Changing Image of the Enemy in the News Discourse of Israeli Newspapers, 1993-1994

conflict & communication online, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2003 www.cco.regener-online.de ISSN 1618-0747 Lea Mandelzis The changing image of the enemy in the news discourse of Israeli newspapers, 1993-1994 Kurzfassung: Geht man davon aus, dass Mediendarstellungen eng mit der öffentlichen Meinung und den Grundlinien der Politik zusammenhängen, so sind sie in Übergangsperioden, während derer Menschen am empfänglichsten für Veränderungen sind, von besonderer Bedeutung. Die Oslo-Abkommen von 1993 markierten eine radikale Veränderung in der israelischen Politik. Die gegenseitige Anerkennung Israels und der Palästinensischen Befreiungsfront (PLO) und der Händedruck zwischen Premierminister Rabin und dem Vorsitzenden Arafat auf dem Rasen des Weißen Hauses im September 1993 stellten dramatische und revolutionäre Schritte dar. Sie spiegelten Veränderungen in der Haltung der israelischen Regierung und der israelischen Medien gegenüber der arabischen Welt im Allgemeinen und den Palästinensern im Besonderen wider. Die vorliegende Studie untersucht Veränderungen, die sich im Nachrichtendiskurs zweier führender Zeitungen abzeichneten, während sich die israelische Gesellschaft von einer Kriegskultur abwandte und stattdessen eine Friedensvision entwickelte. Sie konzentriert sich auf Stereotype und Mythen bezüglich des erklärten Feindes des Staates Israel, nämlich Yasser Arafat und die PLO. Die Untersuchungsstichprobe wurde nach dem Zufallsprinzip aus zwei aufeinanderfolgenden Zeitspannen ausgewählt, die durch die Unterzeichnung der Oslo-Abkommen - einem Wende- und Höhepunkt im Übergang vom Krieg zum Frieden - voneinander getrennt sind. Insgesamt wurden 1186 Zeitungsartikel, die auf den ersten beiden Seiten von Ha’aretz, einer qualitativ hochwertigen Zeitung, und Yedioth Achronoth, einer populäreren Publikation, erschienen waren, inhaltsanalytisch ausgewertet. Die ausgewählten Artikel bezogen sich auf Sicherheit, Frieden und Politik. Die Prä-Oslo-Periode wurde definiert vom 20. -

Did Someone Move Chelm to Israel?

Did someone move Chelm to Israel? January 16, 2011 URL: http://www.sdjewishworld.com/?p=13254 By Danny Bloom Danny Bloom CHIAYI CITY, Taiwan– Daniella Ashkenazy is a seasoned journalist, born in Washington and raised in Silver Spring, Maryland, and living in Israel since 1968. For over two decades she published article in Israel’s leading print media and in newspapers and periodicals abroad including features in Israel’s second-oldest Hebrew newspaper Davar and the Hebrew news weekly Haolam Hazeh . She has also written for the Jerusalem Post and Washington Jewish Week . Much of her work comes with her trademark tongue-in-cheek humor, and one piece she wrote she dubbed “Sabbath Piece of Mind”. Ashkenazy is currently writing an online humor column titled “Chelm-on-the- Med”( www.chelm-on-the-med.com ). She tells San Diego Jewish World that she gets her material from what journalists call “soft news” — actual items published in the Hebrew press in Israel. “I’m an odd-news junkie,” she says in an email exchange from Israel. When asked how her column came to be, she replied: “Israeli news is far too conflict- driven and Israel advocacy is far too cerebral. The fact is, beyond life and death issues, Israel is an outrageously amusing and lively place to live, and I found that many Jews overseas don’t have a clue about the humorous side of Israeli life. So, I decided to cull and collect the silly, the outrageous and even incredibly stupid things that happen here for my online column.” On a roll, she continues: “These odd news stories are only reported in the Hebrew press here. -

Peace, Peace, When There Is No Peace (Israel and the Arabs 1948–1961)

Peace, Peace, When There Is No Peace (Israel and the Arabs 1948–1961) N. Israeli (Akiva Orr and Moshé Machover) Translated from Hebrew by Mark Marshall ii Introduction [to the first edition]................................................................................... xv Chapter 1: “Following Clayton’s Participation in the League’s Meetings”................ 1 Chapter 2: Borders and Refugees ................................................................................. 28 Map: How the Palestinian state was divided............................................................ 42 Chapter 3: Israel and the Powers (1948-1955)............................................................. 83 Chapter 4: Israel and Changes in the Arab World ................................................... 141 Chapter 5: Reprisal Actions......................................................................................... 166 Chapter 6: “The Third Kingdom of Israel” (29/11/56 – 7/3/57).............................. 225 Chapter 7: Sinai War: Post-Mortem........................................................................... 303 Chapter 8: After Suez................................................................................................... 394 Chapter 9: How is the Problem to be Solved?............................................................ 420 Appendices (1999) ......................................................................................................... 498 Appendix 1: Haaretz article on the 30th anniversary of “Operation Qadesh” -

Introduction 1 Mourning Newspapers: Holocaust Commemoration And/ As

Notes Introduction 1. All translations were made by the authors. 2. We do not expand on the discussion of the origins of the word and its rela- tionship with other words, although others have written about it extensively. For example, Tal (1979) wrote an etymological analysis of the word in order to clarify its meaning in relation to the concept of genocide; Ofer (1996b) focused on the process by which the term ‘Shoah’ was adopted in British Mandate Palestine and Israel between 1942 and 1953, and explored its mean- ing in relation to concepts such as ‘heroism’ and ‘resurrection’; and Schiffrin’s works (2001a and 2001b) compare the use of Holocaust-related terms in the cases of the annihilation of European Jewry and the imprisonment of American Japanese in internment camps during the Second World War. See also Alexander (2001), who investigated the growing widespread use of the term ‘Shoah’ among non-Hebrew-speakers. 1 Mourning Newspapers: Holocaust Commemoration and/ as Nation-Building 1. Parts of this chapter have appeared in Zandberg (2010). 2. The Kaddish is a prayer that is part of the daily prayers but it is especially identified with commemorative rituals and said by mourners after the death of close relatives. 3. The Mishnah is the collection (63 tractates) of the codification of the Jewish Oral Law, the Halacha. 4. Knesset Proceedings, First Knesset, Third Sitting, 12 April 1952, Vol. 9, p. 1656. 5. Knesset Proceedings, Second Knesset, Fifth and Ninth Sittings, 25 February 1952, Vol. 11, p. 1409. 6. The 9 of Av (Tish’a B’Av) is a day of fasting and prayers commemorating the destruction of both the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem and the subsequent exile of the Jews from the Land of Israel.