Introduction 1 Mourning Newspapers: Holocaust Commemoration And/ As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Audacity of Holiness Orthodox Jewish Women’S Theater עַ זּוּת שֶׁ Israelבִּ קְ Inדוּשָׁ ה

ׁׁ ְִֶַָּּּהבשות שעזּ Reina Rutlinger-Reiner The Audacity of Holiness Orthodox Jewish Women’s Theater ַעזּּו ֶׁת ש in Israelִּבְקּדו ָׁשה Translated by Jeffrey M. Green Cover photography: Avigail Reiner Book design: Bethany Wolfe Published with the support of: Dr. Phyllis Hammer The Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA Talpiot Academic College, Holon, Israel 2014 Contents Introduction 7 Chapter One: The Uniqueness of the Phenomenon 12 The Complexity of Orthodox Jewish Society in Israel 16 Chapter Two: General Survey of the Theater Groups 21 Theater among ultra-Orthodox Women 22 Born-again1 Actresses and Directors in Ultra-Orthodox Society 26 Theater Groups of National-Religious Women 31 The Settlements: The Forge of Orthodox Women’s Theater 38 Orthodox Women’s Theater Groups in the Cities 73 Orthodox Men’s Theater 79 Summary: “Is there such a thing as Orthodox women’s theater?” 80 Chapter Three: “The Right Hand Draws in, the Left Hand Pushes Away”: The Involvement of Rabbis in the Theater 84 Is Innovation Desirable According to the Torah? 84 Judaism and the Theater–a Fertile Stage in the Culture War 87 The Goal: Creation of a Theater “of Our Own” 88 Differences of Opinion 91 Asking the Rabbi: The Women’s Demand for Rabbinical Involvement 94 “Engaged Theater” or “Emasculated Theater”? 96 Developments in the Relations Between the Rabbis and the Artists 98 1 I use this term, which is laden with Christian connotations, with some trepidation. Here it refers to a large and varied group of people who were not brought up as Orthodox Jews but adopted Orthodoxy, often with great intensity, later in life. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Doing a Real Job: The Evolution in Women's Roles in British Society through the Lens of Female Spies, 1914-1945 Danielle Wirsansky Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES “DOING A REAL JOB”: THE EVOLUTION IN WOMEN’S ROLES IN BRITISH SOCIETY THROUGH THE LENS OF FEMALE SPIES, 1914-1945 By DANIELLE WIRSANSKY A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2018 Danielle Wirsansky defended this thesis on March 6, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Nathan Stoltzfus Professor Directing Thesis Charles Upchurch Committee Member Diane Roberts Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii After the dazzle of day is gone, Only the dark, dark night shows to my eyes the stars; After the clangor of organ majestic, or chorus, or perfect band, Silent, athwart my soul, moves the symphony true. ~Walt Whitman iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am thankful to my major professor, Dr. Nathan Stoltzfus, for his guidance and mentorship the last five years throughout my undergraduate and graduate studies. Without his encouragement, I may never have discovered my passion for history and found myself on the path I am on today. His support has provided me with so many opportunities and the ability to express myself both artistically and academically. -

Regulations and the Rule of Law: a Look at the First Decade of Israel

Keele Law Review, Volume 2 (2021), 45-62 45 ISSN 2732-5679 ‘Hidden’ Regulations and the Rule of Law: A Look at the First decade of Israel Gal Amir* Abstract This article reviews the history of issuing regulations without due promulgation in the first decade of Israel. ‘Covert’ secondary legislation was widely used in two contexts – the ‘austerity policy’ and ‘security’ issues, both contexts intersecting in the state's attitude toward the Palestinian minority, at the time living under military rule. This article will demonstrate that, although analytically the state’s branches were committed to upholding the ‘Rule of Law’, the state used methods of covert legislation, that were in contrast to this principle. I. Introduction Regimes and states like to be associated with the term ‘Rule of Law’, as it is often associated with such terms as ‘democracy’ and ‘human rights’.1 Israel’s Declaration of Independence speaks of a state that will be democratic, egalitarian, and aspiring to the rule of law. Although the term ‘Rule of Law’ in itself is not mentioned in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the declaration speaks of ‘… the establishment of the elected, regular authorities of the State in accordance with the Constitution which shall be adopted by the Elected Constituent Assembly not later than the 1st October 1948.’2 Even when it became clear, in the early 1950s, that a constitution would not be drafted in the foreseeable future, courts and legislators still spoke of ‘Rule of Law’ as an ideal. Following Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, one must examine the existence of the rule of law in young Israel as a ‘category of practice’ requiring reference to a citizen's daily experience, detached from the ‘analytical’ definitions of social scientists, or the high rhetoric of legislators and judges.3 Viewing ‘Rule of Law’ as a category of practice finds Israel in the first decades of its existence in a very different place than its legislators and judges aspired to be. -

Israel-Pakistan Relations Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (JCSS)

P. R. Kumaraswamy Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (JCSS) The purpose of the Jaffee Center is, first, to conduct basic research that meets the highest academic standards on matters related to Israel's national security as well as Middle East regional and international secu- rity affairs. The Center also aims to contribute to the public debate and governmental deliberation of issues that are - or should be - at the top of Israel's national security agenda. The Jaffee Center seeks to address the strategic community in Israel and abroad, Israeli policymakers and opinion-makers and the general public. The Center relates to the concept of strategy in its broadest meaning, namely the complex of processes involved in the identification, mobili- zation and application of resources in peace and war, in order to solidify and strengthen national and international security. To Jasjit Singh with affection and gratitude P. R. Kumaraswamy Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations Memorandum no. 55, March 2000 Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies 6 P. R. Kumaraswamy Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies Tel Aviv University Ramat Aviv, 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel Tel. 972 3 640-9926 Fax 972 3 642-2404 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.tau.ac.il/jcss/ ISBN: 965-459-041-7 © 2000 All rights reserved Graphic Design: Michal Semo Printed by: Kedem Ltd., Tel Aviv Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations 7 Contents Introduction .......................................................................................9 -

Confessions of a Hol

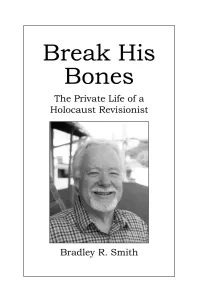

BREAK HIS BONES BREAK HIS BONES by Bradley R. Smith BRADLEY R. SMITH POST OFFICE BOX 439016 SAN YSIDRO, CALIFORNIA 92143 BREAK HIS BONES The Private Life of a Holocaust Revisionist by Bradley R. Smith First Printing: September 2002 Published by Bradley R. Smith Post Office Box 439016 San Ysidro, CA 92143 With the Assistance of Theses & Dissertations Press PO Box 64 Capshaw, AL 35742 ISBN 0-9723756-0-0 Copyright 2002 by Bradley R. Smith Printed in the United States of America AUTHOR’S NOTE It’s a truism. Things are different since 11 September 2001. Of course, things are always different, which is why the open-minded find life so mysterious. The mystery goes beyond mere unpredictability. We don’t know how we come into the world, never learn what we are or what happens to us when we’re finished. It’s been noted by an English sage that, as a matter of fact, we do not come into the world at all, that we come from the world. I am beguiled by the implica- tions of this observation. What it implies lifts up my heart, but this too is mysterious. After radical Islamists expressed their displeasure with American foreign policy at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon it was suggested by some that, having experi- enced our own holocaust, we would never talk about the Jewish Holocaust the way we had talked about it before. On the one hand that would be a mitzvah for those of us who do not personally represent the Holocaust Industry, or profit from it, and in any event do not want to hear about it any longer. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The exact Hebrew name for this affair is the “Yemenite children Affair.” I use the word babies instead of children since at least two thirds of the kidnapped were in fact infants. 2. 1,053 complaints were submitted to all three commissions combined (1033 complaints of disappearances from camps and hospitals in Israel, and 20 from camp Hashed in Yemen). Rabbi Meshulam’s organization claimed to have information about 1,700 babies kidnapped prior to 1952 (450 of them from other Mizrahi ethnic groups) and about 4,500 babies kidnapped prior to 1956. These figures were neither discredited nor vali- dated by the last commission (Shoshi Zaid, The Child is Gone [Jerusalem: Geffen Books, 2001], 19–22). 3. During the immigrants’ stay in transit and absorption camps, the babies were taken to stone structures called baby houses. Mothers were allowed entry only a few times each day to nurse their babies. 4. See, for instance, the testimony of Naomi Gavra in Tzipi Talmor’s film Down a One Way Road (1997) and the testimony of Shoshana Farhi on the show Uvda (1996). 5. The transit camp Hashed in Yemen housed most of the immigrants before the flight to Israel. 6. This story is based on my interview with the Ovadiya family for a story I wrote for the newspaper Shishi in 1994 and a subsequent interview for the show Uvda in 1996. I should also note that this story as well as my aunt’s story does not represent the typical kidnapping scenario. 7. The Hebrew term “Sephardic” means “from Spain.” 8. -

Chapter Two: Who Am I Supposed to Be? Stories Of

El-or/Reserved Seats/Chapter 2/page 137 CHAPTER TWO WHO AM I SUPPOSED TO BE? STORIES OF PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION PROLOGUE 1 EVERY WEDNESDAY It was 10:25 when I parked my car. HaYarkon Street began to fill up. Most of the cars were old ones, and many were plastered with bumper stickers. Some displayed the Na-Nah-Nahma-Nahman Mi-Oman mantra of the Bratislaver Hasidim. Others asked “What, you haven’t become religious yet?” and still others proclaimed “You can’t make a million people shut up.” A young couple emerged from a Subaru. He drew a kipah from his pocket and put it on his head. She wore a tight skirt that reached down below her knees, and stylish sandals without socks. Her hair was loose, and she had a knapsack on her back. They parted at the entrance to the yeshiva. He went in the main door, to the central hall, while she, and I, walked around the back, to the women’s entrance. Not many women were there yet—only about forty. I knew from experience, however, that the lower auditorium, which served during the day as the yeshiva’s dining hall, would slowly fill up. The ramp leading down to the back entrance was dimly lit. Actually the back access drive to the building, it was lined with piles of crates, wooden palettes, and discarded yeshiva gear. The foyer leading into the lower hall had been converted into a small religious emporium. Its shelves were packed with volumes of instruction, children’s books in versions appropriate for Haredi homes, decoratively bound Books of El-or/Reserved Seats/Chapter 2/page 138 Psalms, head kerchiefs, hats, gifts for the Jewish home, candlesticks, pictures of rabbis. -

“Schlaglicht Israel”!

Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 15/18 Aktuelles aus israelischen Tageszeitungen 1.-31. August Die Themen dieser Ausgabe 1. Weiter Protest gegen Nationalstaatsgesetz ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Zwischen Krieg und Waffenstillstand ............................................................................................................................. 3 3. Abschied von Uri Avnery ................................................................................................................................................. 6 4. Medienquerschnitt ............................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Weiter Protest gegen Nationalstaatsgesetz setz zu annullieren. Die Klageführer_innen mei- Der Streit um das Nationalstaatsgesetz ließ nen, dass das neue Gesetz „das Recht auf Israels Abgeordneten trotz Sommerpause der Gleichheit und das Recht auf Würde“ verletze. Knesset keine Ruhe. Im Verlauf der außeror- Justizministerin Ayalet Shaked kommentierte, dentlichen Debatte um das drei Wochen zuvor dass es ein „Erdbeben“ geben werde, wenn die verabschiedete Grundgesetz „Israel – National- Richter gegen das Nationalstaatsgesetz ent- staat des jüdischen Volkes“ schimpfte Oppositi- scheiden. onschefin Zipi Livni vom Zionistischen Lager auf Regierungschef Benjamin Netanyahu, dessen The best answer to post-Zionism Regierung „Hass und Angst“ verbreite. Für den (...) -

HERZLIYA CONFERENCE SPEAKERS and MEMBERS of the BOARD Michal Abadi-Boiangiu Executive Vice President, Comptroller Division, First International Bank of Israel

HERZLIYA CONFERENCE SPEAKERS AND MEMBERS OF THE BOARD Michal Abadi-Boiangiu Executive Vice President, Comptroller Division, First International Bank of Israel. Served as Deputy Director General of the Ministry of Health while also serving as Chairperson of MI Holdings, a position in which she led the privatization of Israel Discount Bank. Holds a B.A. in Economics and Accounting. Leah Achdut Deputy Director General for Research & Planning of the National Insurance Institute of Israel. Served as Director of the Institute for Economic and Social Research, and as Economic Advisor to the Trade Union Federations. Received an M.A. in Economics from the HebrewUniversity of Jerusalem. Aharon Abramovitch Director-General of the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Served as Director- General of the Ministry of Justice, and as a legal advisor for the Jewish Agency, the World Zionist Organization, the World Jewish Restitution Organization and Keren Hayesod. Served as a member of the board of directors of the Israel Museum, the Israel Lands Administration and El Al. Earned a degree in law from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Prof. Oz Almog Professor of Land of Israel Studies at Haifa University. Author of Sabra: The Creation of the New Jew and Farewell to Srulik - Changing Values Among the Israeli Elite. His research areas focus on semiotics, the sociological history of Israeli society, and Israeli popular culture. Holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from Haifa University. Chen Altshuler Founder of the Green Fund and Director of Research at Altshuler Shaham. Previously, Chief Analyst at Altshuler Shaham and director of various public companies. Earned a B.A.