Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Československý Churban Mnichovská Dohoda a Druhá Československá Republika Optikou Sionistického Jišuvu V Palestině (1938–1939)

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra blízkovýchodních studií Československý churban Mnichovská dohoda a druhá československá republika optikou sionistického jišuvu v Palestině (1938–1939) Zbyněk Tarant Plzeň 2020 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra blízkovýchodních studií Československý churban Mnichovská dohoda a druhá československá republika optikou sionistického jišuvu v Palestině (1938–1939) Zbyněk Tarant Plzeň 2020 Československý churban Zbyněk Tarant Vydání publikace bylo schváleno Vědeckou redakcí Západočeské univerzity v Plzni. Recenzenti: prof. PhDr. Jiří Holý, DrSc. doc. PhDr. Blanka Soukupová, CSc. Grafický návrh obálky: Anastasia Vrublevská Typografická úprava: Jakub Pokorný Vydala: Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Univerzitní 2732/8, 301 00 Plzeň Vytiskla: Prekomia s.r.o. Západní 1322/12, 323 00 Plzeň První vydání, 285 stran Plzeň 2020 ISBN 978-80-261-0935-8 © Západočeská univerzita v Plzni © Mgr. Zbyněk Tarant, Ph.D. Abstrakt Kniha Zbyňka Taranta nabízí pohled na mnichovskou doho- du, druhou československou republiku a počátek nacistické okupace českých zemí očima hebrejskojazyčného sionistic- kého tisku v britském mandátu Palestina. Popisuje nešťastný souběh dějinných událostí a výroků klíčových státníků, který mohl způsobit, že se Mnichov stal součástí izraelské sdílené paměti. Když Adolf Hitler 12. září 1938 v atmosféře vrcholící sudetské krize pronesl svůj protičeský projev, použil v něm rovněž příměr Československa s Palestinou. Jeho slova pak nerezonovala pouze u sudetských Němců, kteří je pochopili jako skrytý vzkaz k rozpoutání nepokojů v československém pohraničí, ale i v Palestině, kde jim s narůstajícími obavami naslouchali představitelé sionistického vedení. Mnichovská dohoda se pak pro židovské obyvatelstvo v Palestině (tzv. jišuv) měla stát symbolem zhroucení systému mezinárodních úmluv a záruk, na kterém spočívala samotná existence a budoucnost židovského národního hnutí. -

PART III Global Governance, Democracy and International Labor

C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/7086205/WORKINGFOLDER/DAHAN/9781107087873C09.3D 237 [237–265] 16.12.2015 2:25PM PART III Global governance, democracy and international labor C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/7086205/WORKINGFOLDER/DAHAN/9781107087873C09.3D 238 [237–265] 16.12.2015 2:25PM C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/7086205/WORKINGFOLDER/DAHAN/9781107087873C09.3D 239 [237–265] 16.12.2015 2:25PM 9 Institutional change in transnational labor governance: implementing social standards in public procurement and export credit guarantees anke hassel and nicole helmerich 1. Introduction When more than 1000 workers died and more than 2000 workers were left wounded in the collapse of a factory building in Bangladesh on April 24, 2013, an engaged discussion on labor exploitation started around the world. Media coverage, politicians and firms agreed that conditions in the garment industry in Bangladesh were unacceptable and had to change.1 A flurry of activity consequently erupted culminating in a new labor accord that was signed by major brand firms headquartered outside Bangladesh. Neither the press coverage nor the activities by civil society, govern- ment agencies and global firms on fixing labor standards in Bangladesh make any sense without an understanding of global justice. In the last two decades a new and lively concept of global justice has evolved that has changed the traditional understanding of social justice as being bound to local area and the nation state. Whether global justice is based on social relations,2 interdependent institutional arrangements,3 political respon- sibility4 or shared responsibility,5 the claim is that consumers and firms 1 “U.S. -

Israel in 1982: the War in Lebanon

Israel in 1982: The War in Lebanon by RALPH MANDEL LS ISRAEL MOVED INTO its 36th year in 1982—the nation cele- brated 35 years of independence during the brief hiatus between the with- drawal from Sinai and the incursion into Lebanon—the country was deeply divided. Rocked by dissension over issues that in the past were the hallmark of unity, wracked by intensifying ethnic and religious-secular rifts, and through it all bedazzled by a bullish stock market that was at one and the same time fuel for and seeming haven from triple-digit inflation, Israelis found themselves living increasingly in a land of extremes, where the middle ground was often inhospitable when it was not totally inaccessible. Toward the end of the year, Amos Oz, one of Israel's leading novelists, set out on a journey in search of the true Israel and the genuine Israeli point of view. What he heard in his travels, as published in a series of articles in the daily Davar, seemed to confirm what many had sensed: Israel was deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, riven by two political philosophies, two attitudes toward Jewish historical destiny, two visions. "What will become of us all, I do not know," Oz wrote in concluding his article on the develop- ment town of Beit Shemesh in the Judean Hills, where the sons of the "Oriental" immigrants, now grown and prosperous, spewed out their loath- ing for the old Ashkenazi establishment. "If anyone has a solution, let him please step forward and spell it out—and the sooner the better. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Israeli Media Self-Censorship During the Second Lebanon War

conflict & communication online, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2019 www.cco.regener-online.de ISSN 1618-0747 Sagi Elbaz & Daniel Bar-Tal Voluntary silence: Israeli media self-censorship during the Second Lebanon War Kurzfassung: Dieser Artikel beschreibt die Charakteristika der Selbstzensur im Allgemeinen, und insbesondere in den Massenmedien, im Hinblick auf Erzählungen von politischer Gewalt, einschließlich Motivation und Auswirkungen von Selbstzensur. Es präsentiert zunächst eine breite theoretische Konzeptualisierung der Selbstzensur und konzentriert sich dann auf seine mediale Praxis. Als Fallstudie wurde die Darstellung des Zweiten Libanonkrieges in den israelischen Medien untersucht. Um Selbstzensur als einen der Gründe für die Dominanz hegemonialer Erzählungen in den Medien zu untersuchen, führten die Autoren Inhaltsanalysen und Tiefeninterviews mit ehemaligen und aktuellen Journalisten durch. Die Ergebnisse der Analysen zeigen, dass israelische Journalisten die Selbstzensur weitverbreitet einsetzen, ihre Motivation, sie zu praktizieren, und die Auswirkungen ihrer Anwendung auf die Gesellschaft. Abstract: This article describes the characteristics of self-censorship in general, specifically in mass media, with regard to narratives of political violence, including motivations for and effects of practicing self-censorship. It first presents a broad theoretical conceptualization of self-censorship, and then focuses on its practice in media. The case study examined the representation of The Second Lebanon War in the Israeli national media. The authors carried out content analysis and in-depth interviews with former and current journalists in order to investigate one of the reasons for the dominance of the hegemonic narrative in the media – namely, self-censorship. Indeed, the analysis revealed widespread use of self-censorship by Israeli journalists, their motivations for practicing it, and the effects of its use on the society. -

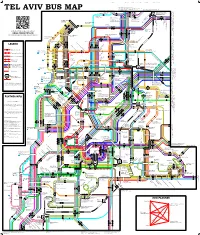

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Session of the Zionist General Council

SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1967 Addresses,; Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE n Library י»B I 3 u s t SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1966 Addresses, Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM iii THE THIRD SESSION of the Zionist General Council after the Twenty-sixth Zionist Congress was held in Jerusalem on 8-15 January, 1967. The inaugural meeting was held in the Binyanei Ha'umah in the presence of the President of the State and Mrs. Shazar, the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Knesset, Cabinet Ministers, the Chief Justice, Judges of the Supreme Court, the State Comptroller, visitors from abroad, public dignitaries and a large and representative gathering which filled the entire hall. The meeting was opened by Mr. Jacob Tsur, Chair- man of the Zionist General Council, who paid homage to Israel's Nobel Prize Laureate, the writer S.Y, Agnon, and read the message Mr. Agnon had sent to the gathering. Mr. Tsur also congratulated the poetess and writer, Nellie Zaks. The speaker then went on to discuss the gravity of the time for both the State of Israel and the Zionist Move- ment, and called upon citizens in this country and Zionists throughout the world to stand shoulder to shoulder to over- come the crisis. Professor Andre Chouraqui, Deputy Mayor of the City of Jerusalem, welcomed the delegates on behalf of the City. -

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION a Project Of

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A project of edited by Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman Remember the Women Institute, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation founded in 1997 and based in New York City, conducts and encourages research and cultural activities that contribute to including women in history. Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel is the founder and executive director. Special emphasis is on women in the context of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Through research and related activities, including this project, the stories of women—from the point of view of women—are made available to be integrated into history and collective memory. This handbook is intended to provide readers with resources for using theatre to memorialize the experiences of women during the Holocaust. Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A Project of Remember the Women Institute By Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman This resource handbook is dedicated to the women whose Holocaust-related stories are known and unknown, told and untold—to those who perished and those who survived. This edition is dedicated to the memory of Nava Semel. ©2019 Remember the Women Institute First digital edition: April 2015 Second digital edition: May 2016 Third digital edition: April 2017 Fourth digital edition: May 2019 Remember the Women Institute 11 Riverside Drive Suite 3RE New York,NY 10023 rememberwomen.org Cover design: Bonnie Greenfield Table of Contents Introduction to the Fourth Edition ............................................................................... 4 By Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel, Founder and Director, Remember the Women Institute 1. Annotated Bibliographies ....................................................................................... 15 1.1. -

Dr. Dalia Liran-Alper – Curriculum Vitae

The College of Management-Academic Studies April 2008 Date: September 16, 2014 Dr. Dalia Liran-Alper – Curriculum Vitae Personal Details: Academic Degree: PhD Phone Number at: Mobile: 0546-665480 School/Department: School of Media Studies, The College of Management-Academic Studies Academic Education: Name of higher education Year degree Year/s institution Subject Degree or diploma received 1976-1979 Hebrew University of International Relations, BA 1980 Jerusalem History 1980-1983 Hebrew University of Communication MA (practical 1983 Jerusalem program) 1989-1994 Hebrew University of Communication Thesis (theory 1994 Jerusalem program) 1998-2005 University of Haifa Education, Communication PhD 2005 M.A. and Ph.D. Details: (Institution, Adviser/s, Title) Masters thesis: Media representation of women in politics: Are they still “Domineering dowagers and scheming concubines”? (1994) Adviser: Prof. Gadi Wolfsfeld Doctoral thesis: Sociocultural construction of gendered identity among girls attending dance classes in Israel (2004) Adviser: Tamar Katriel Further Studies: Teaching license program, Levinsky College of Education, Tel Aviv (1995-1996) Academic Experience – Teaching: Year/s Name of institution Department/program Rank/position 1980-1992 The Open University International relations, Social patterns Instructor in Israel, Mass media, and others 1993-1997 Levinsky College of Faculty of Education, Teacher Lecturer Education Training 2011-1989 Beit Berl Academic School of Education, Department of Lecturer College Social Sciences 1994-2004 -

Mythos Israel Israel Dr

60 Jahre Planung im neuen Jüdischen Staat Israel = 60 Jahre Enteignung und Ausgrenzung der autochthonen palästinensischen Bevölkerung Dr. Viktoria Waltz, München 9.12.09 60 Jahre Planung im neuen Jüdischen Staat Mythos Israel Israel Dr. Viktoria Waltz 9.12.09 = 60 Jahre Enteignung und Ausgrenzung der autochthonen palästinensischen Bevölkerung 0. Ausgangssituation und Probleme der Neugründung 15. Mai 1948 zionistische Kolonien, palästinensische Orte Bevölkerungsverteilung Bodeneigentum Machtverhältnisse 1. Verfassung und Bürgerrechte 2. Einwanderung und Ansiedlung von Immigranten 3. Raumplanung Landenteignung Organe und Planungen Nationalplan 1950 Kibbuzim und Moshavim New Towns (Beispiele Kiryat Gad, Ashkelon, Ramleh, Jaffa) Wasser, Parks Planungssystem Kartenübersicht UN-Teilung 1947 Topographie und Lage ‚Tourismus„-Karte, 56,7% ‚‚jewish„ nach 1948 (70%„ jewish„) - mit ‚Golan„ (100%?) Letzte Phase vor der Staatsgründung 1948 Kolonien 1945 Palästinensische Dörfer und Städte Die Utopie von 1945 einem ‚leeren Land‘ 1948 Lage des bis 1946 durch den JNF gekauften Landes Quellen: Grannott 1956, Richter 1969, Waltz/Zschiesche 1986 Situation 14. May 1948 im Staatsgebiet Israel • Jüdische Seite Palästinensische Seite ca. 700.000 EW, davon ca. 156.000 EW, und ca. 330.812 ca. 50% Geflohene 750.000 Vertriebene (Nakba) aus Europa (Faschismus) Konzentriert mit 90% im Konzentriert mit 80% in den Inneren des Landes: Küstenstädten zwischen: - Negev (Beduinen) - Tel Aviv und - ‚Dreieck„ um Um el Fahem - Haifa - Galiläa mit Nazareth Als jüdische Mehrheit -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim.