The Arabs in Israel 1948-1966

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Schlaglicht Israel”!

Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 15/18 Aktuelles aus israelischen Tageszeitungen 1.-31. August Die Themen dieser Ausgabe 1. Weiter Protest gegen Nationalstaatsgesetz ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Zwischen Krieg und Waffenstillstand ............................................................................................................................. 3 3. Abschied von Uri Avnery ................................................................................................................................................. 6 4. Medienquerschnitt ............................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Weiter Protest gegen Nationalstaatsgesetz setz zu annullieren. Die Klageführer_innen mei- Der Streit um das Nationalstaatsgesetz ließ nen, dass das neue Gesetz „das Recht auf Israels Abgeordneten trotz Sommerpause der Gleichheit und das Recht auf Würde“ verletze. Knesset keine Ruhe. Im Verlauf der außeror- Justizministerin Ayalet Shaked kommentierte, dentlichen Debatte um das drei Wochen zuvor dass es ein „Erdbeben“ geben werde, wenn die verabschiedete Grundgesetz „Israel – National- Richter gegen das Nationalstaatsgesetz ent- staat des jüdischen Volkes“ schimpfte Oppositi- scheiden. onschefin Zipi Livni vom Zionistischen Lager auf Regierungschef Benjamin Netanyahu, dessen The best answer to post-Zionism Regierung „Hass und Angst“ verbreite. Für den (...) -

Iraqi Jews: a History of Mass Exodus by Abbas Shiblak, Saqi, 2005, 215 Pp

Iraqi Jews: A History of Mass Exodus by Abbas Shiblak, Saqi, 2005, 215 pp. Rayyan Al-Shawaf The 2003 toppling of Saddam Hussein’s Baath regime and the occupation of Iraq by Allied Coalition Forces has served to generate a good deal of interest in Iraqi history. As a result, in 2005 Saqi reissued Abbas Shiblak’s 1986 study The Lure of Zion: The Case of the Iraqi Jews. The revised edition, which includes a preface by Iraq historian Peter Sluglett as well as minor additions and modifications by the author, is entitled The Iraqi Jews: A History of Mass Exodus. Shiblak’s book, which deals with the mass immigration of Iraqi Jews to Israel in 1950-51, is important both as one of the few academic studies of the subject as well as a reminder of a time when Jews were an integral part of Iraq and other Arab countries. The other significant study of this subject is Moshe Gat’s The Jewish Exodus from Iraq, 1948-1951, which was published in 1997. A shorter encapsulation of Gat’s argument can be found in his 2000 Israel Affairs article Between‘ Terror and Emigration: The Case of Iraqi Jewry.’ Because of the diametrically opposed conclusions arrived at by the authors, it is useful to compare and contrast their accounts. In fact, Gat explicitly refuted many of Shiblak’s assertions as early as 1987, in his Immigrants and Minorities review of Shiblak’s The Lure of Zion. It is unclear why Shiblak has very conspicuously chosen to ignore Gat’s criticisms and his pointing out of errors in the initial version of the book. -

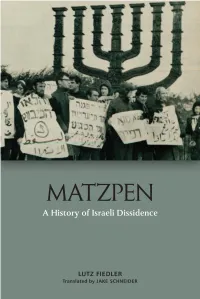

9781474451185 Matzpen Intro

MATZPEN A History of Israeli Dissidence Lutz Fiedler Translated by Jake Schneider 66642_Fiedler.indd642_Fiedler.indd i 331/03/211/03/21 44:35:35 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com Original version © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, 2017 English translation © Jake Schneider, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd Th e Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5116 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5118 5 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5119 2 (epub) Th e right of Lutz Fiedler to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Originally published in German as Matzpen. Eine andere israelische Geschichte (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017) Th e translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Th yssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Offi ce, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association). -

The Changing Image of the Enemy in the News Discourse of Israeli Newspapers, 1993-1994

conflict & communication online, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2003 www.cco.regener-online.de ISSN 1618-0747 Lea Mandelzis The changing image of the enemy in the news discourse of Israeli newspapers, 1993-1994 Kurzfassung: Geht man davon aus, dass Mediendarstellungen eng mit der öffentlichen Meinung und den Grundlinien der Politik zusammenhängen, so sind sie in Übergangsperioden, während derer Menschen am empfänglichsten für Veränderungen sind, von besonderer Bedeutung. Die Oslo-Abkommen von 1993 markierten eine radikale Veränderung in der israelischen Politik. Die gegenseitige Anerkennung Israels und der Palästinensischen Befreiungsfront (PLO) und der Händedruck zwischen Premierminister Rabin und dem Vorsitzenden Arafat auf dem Rasen des Weißen Hauses im September 1993 stellten dramatische und revolutionäre Schritte dar. Sie spiegelten Veränderungen in der Haltung der israelischen Regierung und der israelischen Medien gegenüber der arabischen Welt im Allgemeinen und den Palästinensern im Besonderen wider. Die vorliegende Studie untersucht Veränderungen, die sich im Nachrichtendiskurs zweier führender Zeitungen abzeichneten, während sich die israelische Gesellschaft von einer Kriegskultur abwandte und stattdessen eine Friedensvision entwickelte. Sie konzentriert sich auf Stereotype und Mythen bezüglich des erklärten Feindes des Staates Israel, nämlich Yasser Arafat und die PLO. Die Untersuchungsstichprobe wurde nach dem Zufallsprinzip aus zwei aufeinanderfolgenden Zeitspannen ausgewählt, die durch die Unterzeichnung der Oslo-Abkommen - einem Wende- und Höhepunkt im Übergang vom Krieg zum Frieden - voneinander getrennt sind. Insgesamt wurden 1186 Zeitungsartikel, die auf den ersten beiden Seiten von Ha’aretz, einer qualitativ hochwertigen Zeitung, und Yedioth Achronoth, einer populäreren Publikation, erschienen waren, inhaltsanalytisch ausgewertet. Die ausgewählten Artikel bezogen sich auf Sicherheit, Frieden und Politik. Die Prä-Oslo-Periode wurde definiert vom 20. -

Did Someone Move Chelm to Israel?

Did someone move Chelm to Israel? January 16, 2011 URL: http://www.sdjewishworld.com/?p=13254 By Danny Bloom Danny Bloom CHIAYI CITY, Taiwan– Daniella Ashkenazy is a seasoned journalist, born in Washington and raised in Silver Spring, Maryland, and living in Israel since 1968. For over two decades she published article in Israel’s leading print media and in newspapers and periodicals abroad including features in Israel’s second-oldest Hebrew newspaper Davar and the Hebrew news weekly Haolam Hazeh . She has also written for the Jerusalem Post and Washington Jewish Week . Much of her work comes with her trademark tongue-in-cheek humor, and one piece she wrote she dubbed “Sabbath Piece of Mind”. Ashkenazy is currently writing an online humor column titled “Chelm-on-the- Med”( www.chelm-on-the-med.com ). She tells San Diego Jewish World that she gets her material from what journalists call “soft news” — actual items published in the Hebrew press in Israel. “I’m an odd-news junkie,” she says in an email exchange from Israel. When asked how her column came to be, she replied: “Israeli news is far too conflict- driven and Israel advocacy is far too cerebral. The fact is, beyond life and death issues, Israel is an outrageously amusing and lively place to live, and I found that many Jews overseas don’t have a clue about the humorous side of Israeli life. So, I decided to cull and collect the silly, the outrageous and even incredibly stupid things that happen here for my online column.” On a roll, she continues: “These odd news stories are only reported in the Hebrew press here. -

Peace, Peace, When There Is No Peace (Israel and the Arabs 1948–1961)

Peace, Peace, When There Is No Peace (Israel and the Arabs 1948–1961) N. Israeli (Akiva Orr and Moshé Machover) Translated from Hebrew by Mark Marshall ii Introduction [to the first edition]................................................................................... xv Chapter 1: “Following Clayton’s Participation in the League’s Meetings”................ 1 Chapter 2: Borders and Refugees ................................................................................. 28 Map: How the Palestinian state was divided............................................................ 42 Chapter 3: Israel and the Powers (1948-1955)............................................................. 83 Chapter 4: Israel and Changes in the Arab World ................................................... 141 Chapter 5: Reprisal Actions......................................................................................... 166 Chapter 6: “The Third Kingdom of Israel” (29/11/56 – 7/3/57).............................. 225 Chapter 7: Sinai War: Post-Mortem........................................................................... 303 Chapter 8: After Suez................................................................................................... 394 Chapter 9: How is the Problem to be Solved?............................................................ 420 Appendices (1999) ......................................................................................................... 498 Appendix 1: Haaretz article on the 30th anniversary of “Operation Qadesh” -

Introduction 1 Mourning Newspapers: Holocaust Commemoration And/ As

Notes Introduction 1. All translations were made by the authors. 2. We do not expand on the discussion of the origins of the word and its rela- tionship with other words, although others have written about it extensively. For example, Tal (1979) wrote an etymological analysis of the word in order to clarify its meaning in relation to the concept of genocide; Ofer (1996b) focused on the process by which the term ‘Shoah’ was adopted in British Mandate Palestine and Israel between 1942 and 1953, and explored its mean- ing in relation to concepts such as ‘heroism’ and ‘resurrection’; and Schiffrin’s works (2001a and 2001b) compare the use of Holocaust-related terms in the cases of the annihilation of European Jewry and the imprisonment of American Japanese in internment camps during the Second World War. See also Alexander (2001), who investigated the growing widespread use of the term ‘Shoah’ among non-Hebrew-speakers. 1 Mourning Newspapers: Holocaust Commemoration and/ as Nation-Building 1. Parts of this chapter have appeared in Zandberg (2010). 2. The Kaddish is a prayer that is part of the daily prayers but it is especially identified with commemorative rituals and said by mourners after the death of close relatives. 3. The Mishnah is the collection (63 tractates) of the codification of the Jewish Oral Law, the Halacha. 4. Knesset Proceedings, First Knesset, Third Sitting, 12 April 1952, Vol. 9, p. 1656. 5. Knesset Proceedings, Second Knesset, Fifth and Ninth Sittings, 25 February 1952, Vol. 11, p. 1409. 6. The 9 of Av (Tish’a B’Av) is a day of fasting and prayers commemorating the destruction of both the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem and the subsequent exile of the Jews from the Land of Israel. -

Preface 1 Celebrity Politics: a Theoretical and Historical Perspective

Notes Preface 1. D. M. West and J. M. Orman (2003) Celebrity Politics (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall). 2. G. Turner (2006) ‘The Mass Production of Celebrity “Celetoids”, Reality TV and the “Demotic Turn”’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, 9(2), 153–65. 3. N. Ribke (2015) ‘Entertainment Politics: Brazilian Celebrities’ Transition to Politics: Recent History and Main Patterns’, Media Culture & Society, 31(3), 35–49. 4. See Chapter 5. 5. West and Orman, Celebrity Politics; D. M. West (2007) ‘Angelina, Mia, and Bono: Celebrities and International Development’, Development, 2, 1–9; N. Wood and K. C. Herbst (2007) ‘Political Star Power and Political Parties: Does Celebrity Endorsement Win First-time Votes?’, Journal of Political Marketing, 6(2–3), 141–58. 6. J. Stanyer (2013) Intimate Politics (Cambridge: Polity); J. Alexander (2010) ‘Barack Obama Meets Celebrity Metaphor’, Society, 47(5), 410–18; D. Kellner (2009) ‘Barack Obama and Celebrity Spectacle’, International Journal of Communication, 3, 715–41. 7. Printed press journalists are not considered for this study since their migration to politics and the relation of their profession with the field of politics precedes the celebrity culture phenomenon. On this issue, see M. Weber (1976) ‘Towards a Sociology of the Press’, Journal of Communication, 26(3), 96–101. 8. On this issue, see S. Livingstone (2003) ‘On the Challenges of Cross- National Comparative Media Research’, European Journal of Communication, 18(4), 477–500. 1 Celebrity Politics: a Theoretical and Historical Perspective 1. C. W. Mills (1999) The Power Elite (London: Oxford University Press), pp. 90–1. 2. Mills, The Power Elite, p. -

2018 Haggadah (.Pdf)

Note: italicized text is sung 2018 Haggadah Compiled by only by the leader. Mauro Cutz Braunstein 2018 1. Kadesh Urchatz (p. 19) British Christian ("New Britain") b 3 ™ j ˙™ ˙ & 4 ˙ œ œ ˙ œ ˙ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ ‹ œ ˙ œ Ka- desh, ur - chatz, kar - pas, ya- chatz, ma - gid, rach tzah, mo- tzi, ma - tzah, j b ˙ ™ & œ œ œ ˙ œ ˙ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙™ ˙ ‹ ˙ œ ma - ror, ko - rech, shul chan o - rech, tza - fun, ba - rech, ha- lel, nir - tzah. Kadesh, urchatz, karpas, yachatz, magid, rachtzah, motzi, matzah, maror, korech, shulchan orech, tzafun, barech, halel, nirtzah. 2. Vaychulu (Friday night) (p. 20) ◊ Vayhi erev vayhi voker: Moroccan 3 3 bb b œ œ œ œ œ œ & b œ œ œ œ œ œ œ nœ œ œ œ œ œ œ œœœnœœ ˙ œ ‹ œ œ Yom ha-shi- shi. Vay-chu - lu ha-sha-ma - yim v' ha-a-retz v' - chol tz' - va - am. Vay bb b œ ™ œ œ & b œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œnœœ œ œ œ œ ‹ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ chal E-lo-him ba - yom ha- sh'- vi - i m' lach - to a - sher a- sah, va - yish-bot ba - 3 bb b ™ œ œ œ™œ œ œ œ™ œ & b œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œ œ nœœ˙ œ œ œœ ‹ œ œ yom ha - sh' - vi - i mi-kol m' lach-to a -sher a - sah. Vay-va - rech E - lo- him et 3 bb b œ ˙ œ œ œ™ œ & b œ œ œ œnœ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ ‹ ˙ yom ha-sh' vi -i vay-ka-desh o - to, ki vo sha-vat mi-kol m' lach-to a- bb b œ ™ œ & b œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ nœ œ œ nœ ˙ ‹ œ sher ba-ra E - lo -him la - a - - sot. -

Conformity and Dissent in Israeli Soldiers' Letters from the Suez Crisis, 1953–1957

―ARAB MOTHERS ALSO CRY‖: CONFORMITY AND DISSENT IN ISRAELI SOLDIERS' LETTERS FROM THE SUEZ CRISIS, 1953–1957 Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arab Studies By Shay Hazkani, B.A. Washington, DC April 28, 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Shay Hazkani All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS At Georgetown University, I had the pleasure of working with a group of intellectually engaging mentors. I thank Dr. Osama Abi-Mershed for his continuing advice on this project. He assisted me in making sense of hundreds of disparate and often contradicting letters. Dr. Rochelle Davis read through my first few attempts at historicizing memories and provided much needed direction. I also would like to thank Dr. Judith E. Tucker, who encouraged me to pursue an academic track. At Tel-Aviv University, I thank Dr. Yoav Alon from the Department of Middle Eastern and African History for his continuing support for my project and academic course. A Student Grant for Research from the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University facilitated the archival research. I also want to thank the staff at the IDF Archive for their work at locating and declassifying the sources at my request. I am also grateful to Daniella Jaeger and Alexander Blake Ewing for their close copy- editing throughout my academic endeavor in the United States. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I: The ―Conventional Wisdom‖, or the Doxa, of the Army Field ......................................... 13 Chapter 1: The Sabra Elite and its Discourse .......................................................................... -

Israeli Public Opinion and the Camp David Accords Daniel L

Hamline University DigitalCommons@Hamline Departmental Honors Projects College of Liberal Arts Spring 2015 The oP ssibility of Peace: Israeli Public Opinion and the Camp David Accords Daniel L. Gerdes Hamline University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/dhp Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Recommended Citation Gerdes, Daniel L., "The osP sibility of Peace: Israeli Public Opinion and the Camp David Accords" (2015). Departmental Honors Projects. 28. https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/dhp/28 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts at DigitalCommons@Hamline. It has been accepted for inclusion in Departmental Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Hamline. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Possibility of Peace: Israeli Public Opinion and the Camp David Accords Daniel Gerdes An Honors Thesis Submitted for partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in History from Hamline University 28 April 2015 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………… 1 In Search of Publius………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Newspapers: Understanding the Israeli Press…………………………………………… 6 Egypt-Israeli Relations between 1973 War and Camp David Accords…………………. 11 Camp David: 1978………………………………………………………………………. 13 From Trauma to Treaty………………………………………………………………………. 19 The Yom Kippur War – Oct. 1973……………………………………………………… 19 Postwar Negotiations – Nov. 1973 to Sept. 1974……………………………………….. 29 President Sadat’s Visit – Nov. 1977…………………………………………………….. 33 Camp David Accords – Sept. 1978……………………………………………………… 37 The Press in Israel………………………………………………………………………. -

What Is Good Journalism? Comparing Israeli Public and Journalists’ Perspectives

Journalism Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) Vol. 7(2): 152–173 DOI: 10.1177/1464884906062603 ARTICLE What is good journalism? Comparing Israeli public and journalists’ perspectives Yariv Tsfati University of Haifa, Israel Oren Meyers University of Haifa, Israel Yoram Peri Tel Aviv University, Israel ABSTRACT The frequent referencing of service to the public interest as a core professional journalistic value raises the question of the correspondence between the perception of journalists and the public as to what constitutes good and bad journalism. In this study, a sample of Israeli journalists and a sample of the Israeli public were asked a series of questions about the core values and practices of journalism. Results suggest four major conclusions: first, Israeli journalists have a clear, relatively uniform perception of what constitutes worthy journalism. Second, journalists and the public differ in the degrees of significance they assign to various journalistic norms and practices. Third, the public is slightly more positive in its overall assessment of the Israeli media in comparison with the journalists. Finally, the two general assessments are constituted by different, or even opposing, components. KEY WORDS Israel journalistic values public opinion Journalists are often depicted as ‘watchdogs’ or ‘advocates’. Both metaphors imply that journalists should operate ‘on behalf of the public’, provide it with information necessary for democratic decision-making, defend society from corruption, and deal with issues that the public cares about. Similarly, journal- istic discourse often uses the rhetoric of mission, duty and service when discussing the relationship between journalists and their audiences. As a typical journalistic code of ethics declares: ‘The public’s right to know about matters of importance is paramount.