Modernist Art in the Magazines, 1893-1922 This Talk Is Meant to Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intangible Heritage(S): an Interplay of Design, Social and Cultural Critiques of the Built Environment

TANGIBLE - INTANGIBLE HERITAGE(S): AN INTERPLAY OF DESIGN, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CRITIQUES OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT • Paper / Proposal Title: ‘ARCHITECTS – WHERE IS YOUR VORTEX? VORTICISM, THE CITY AND URBAN EXPERIENCE • Author(s) Name: Dr. JONATHAN BLACK FRSA • University or Company Affiliation: KINGSTON SCHOOL OF ART, KINGSTON UNIVERSITY • Presentation Method. I would like to: i. present in person (with/without a written paper)* • Abstract (300 words): From its conception in the spring of 1914 the British avant garde art movement known as Vorticism was obsessed with the city and urban existence as central to the forward march of technologically innovative modernity. Indeed, the movement largely owed its very name to the American poet Ezra Pound having already identified London as the ‘great modern vortex’, the end point for all the energies of modern life and of British/Imperial power. My paper is rooted in many years of research into Vorticism and British Art before, during and after the First World War. It will focus on some of the many images that evoked the strikingly positive Vorticist vision of the city – one that as much looked to the example of vertically vertiginous New York as that by experimental thinkers on the European continent – by leading adherents of the movement such as: Wyndham Lewis, Edward Wadsworth, Frederick Etchells, Jessica Dismorr and Helen Saunders. Living in London much of their imagery was indebted to that city. However, examples will be discussed alongside a group of woodcut prints produced c. 1914-18 by Wadsworth inspired by the cities and industrial towns of his native Yorkshire such as Leeds, Bradford, Halifax and Huddersfield. -

Claes-Göran Holmberg

fLaMMan claes-Göran holmberg Precursors swedish avant-garde groups were very late in founding their own magazines. in france and Germany, little magazines had been pub- lished continuously from the romantic era onwards. a magazine was an ideal platform for the consolidation of a new movement in its formative phase. it was a collective thrust at the heart of the enemy: the older generation, the academies, the traditionalists. By showing a united front (through programmatic declarations, manifestos, es- says etc.) you assured the public that you were to be reckoned with. almost every new artist group or current has tried to create a mag- azine to define and promote itself. the first swedish little magazine to embrace the symbolist and decadent movements of fin-de-siècle europe was Med pensel och penna (With paintbrush and pen, 1904-1905), published in Uppsala by the society of “Les quatres diables”, a group of young poets and students engaged in aestheticism and Baudelaire adulation. Mem- bers were the poet and student in slavic languages sigurd agrell (1881-1937), the student and later professor of art history harald Brising (1881-1918), the student of philosophy and later professor of psychology John Landquist (1881-1974), and the author sven Lidman (1882-1960); the poet sigfrid siwertz (1882-1970) also joined the group later. the magazine did not leave any great impact on swedish literature but it helped to spread the Jugend style of illu- stration, the contemporary love-hate relationship with the city and the celebration of the intoxicating powers of beauty and deca- dence. -

DER BLAUE REITER Textpuzzle

MDS 3.2 Unterrichtsprojekte in der Sekundarstufe Freiburg vom 29.06. bis 19.07.2014 Ozana Klein, Gabriele Weiß, Alexandra Effe DER BLAUE REITER Textpuzzle Der Blaue Reiter ist die Bezeichnung für eine Künstlergruppe Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts in München. Der Name wurde von Wassily Kandinsky und Franz Marc gewählt. Beide waren Maler und Künstler. Kandinsky hatte bereits 1909 ein Bild … … mit dem Titel „Der Blaue Reiter“ geschaffen. Was die Bezeichnung betrifft, sagte Kandinsky: „Den Namen „Der Blaue Reiter“ erfanden wir am Kaffeetisch in der Gartenlaube in Sindelsdorf. Beide liebten wir Blau: Marc – Pferde und ich – Reiter. So kam der Name … … von selbst.“ Zur Farbe Blau schrieb Kandinsky einmal: „Sie weckt in ihm die Sehnsucht nach Reinem und Übersinnlichem. Es ist die Farbe des Himmels“. August Macke und Franz Marc waren überzeugt, dass jeder Mensch eine innere und eine äußere Erlebniswelt besitzt, die durch die Kunst … … zusammengeführt werden. Außerdem glaubten sie an die Gleichberechtigung aller Kunstformen. Faktisch zählt der Blaue Reiter zum Expressionismus.Kandinsky und Marc gehörten zuerst einer anderen Künstlergruppe an. Sie hieß „Neue Künstlervereinigung München“. Aber besonders Kandinsky hatte … …immer öfter Streit mit den eher traditionell denkenden Mitgliedern der Gruppe wegen seiner sehr abstrakten Malerei und so traten er und Franz Marc 1911 aus. Sie organisierten noch im selben Jahr die erste Blaue-Reiter-Ausstellung, die … … ein großer Erfolg wurde. Die Künstlergruppe „Der Blaue Reiter“ war geboren. Von Anfang an zur Gruppe gehörten auch August Macke und Gabriele Münter, die langjährige Lebensgefährtin von Kandinsky. Sie lebten zusammen in … …Murnau, in der Nähe von Garmisch Partenkirchen im Voralpenland. Ganz in der Nähe, in Sindelsdorf, wohnten Franz und Marie Marc, zu denen sie engen Kontakt hatten. -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

Orpheu Et Al. Modernism, Women, and the War

Orpheu et al. Modernism, Women, and the War M. Irene Ramalho-Santos* Keywords Little magazines, Poetry, Modernism, The Great War, Society, Sexual mores. Abstract The article takes off from Orpheu, the little magazine at the origin of Portuguese modernism, to reflect, from a comparative perspective, on the development of modernist poetry in the context of the Great War and the social changes evolving during the first decades of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic. Palavras-chave “Little magazines,” Poesia, Modernismo, A Grande Guerra, Sociedade, Costumes sexuais. Resumo O artigo parte de Orpheu, a revista que dá origem ao modernismo português, para reflectir, numa perspectiva comparada, soBre o desenvolvimento da poesia modernista no contexto da Grande Guerra e das mudanças sociais emergentes nas primeiras décadas do século XX dos dois lados do Atlântico. * Universidade de CoimBra; University of Wisconsin-Madison. Ramalho Santos Orpheu et al. It is frequently repeated in the relevant scholarship that Western literary and artistic modernism started in little magazines.1 The useful online Modernist Journals Project (Brown University / Tulsa University), dealing so far only with American and British magazines, uses as its epigraph the much quoted phrase: “modernism began in the magazines”, see SCHOLES and WULFMAN (2010) and BROOKER and THACKER (2009-2013). With two issues published in 1915 and a third one stopped that same year in the galley proofs for lack of funding, the Portuguese little magazine Orpheu inaugurated modernism in Portugal pretty much at the same time as all the other major little magazines in Europe and the United States. This is interesting, given the proverbial belatedness of Portuguese accomplishments, and no less interesting the fact that, like everywhere else, Orpheu was followed, in Portugal as well, By a number of other little magazines. -

Sheila Watson Fonds Finding Guide

SHEILA WATSON FONDS FINDING GUIDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS JOHN M. KELLY LIBRARY | UNIVERSITY OF ST. MICHAEL’S COLLEGE 113 ST. JOSEPH STREET TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA M5S 1J4 ARRANGED AND DESCRIBED BY ANNA ST.ONGE CONTRACT ARCHIVIST JUNE 2007 (LAST UPDATED SEPTEMBER 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS TAB Part I : Fonds – level description…………………………………………………………A Biographical Sketch HiStory of the Sheila WatSon fondS Extent of fondS DeScription of PaperS AcceSS, copyright and publiShing reStrictionS Note on Arrangement of materialS Related materialS from other fondS and Special collectionS Part II : Series – level descriptions………………………………………………………..B SerieS 1.0. DiarieS, reading journalS and day plannerS………………………………………...1 FileS 2006 01 01 – 2006 01 29 SerieS 2.0 ManuScriptS and draftS……………………………………………………………2 Sub-SerieS 2.1. NovelS Sub-SerieS 2.2. Short StorieS Sub-SerieS 2.3. Poetry Sub-SerieS 2.4. Non-fiction SerieS 3.0 General correSpondence…………………………………………………………..3 Sub-SerieS 3.1. Outgoing correSpondence Sub-SerieS 3.2. Incoming correSpondence SerieS 4.0 PubliShing records and buSineSS correSpondence………………………………….4 SerieS 5.0 ProfeSSional activitieS materialS……………………………………………………5 Sub-SerieS 5.1. Editorial, collaborative and contributive materialS Sub-SerieS 5.2. Canada Council paperS Sub-SerieS 5.3. Public readingS, interviewS and conference material SerieS 6.0 Student material…………………………………………………………………...6 SerieS 7.0 Teaching material………………………………………………………………….7 Sub-SerieS 7.1. Elementary and secondary school teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.2. UniverSity of BritiSh Columbia teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.3. UniverSity of Toronto teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.4. UniverSity of Alberta teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.5. PoSt-retirement teaching material SerieS 8.0 Research and reference materialS…………………………………………………..8 Sub-serieS 8.1. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

Call#: NXSSO.A1 T68 2016 ~ 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1-C .,.0

ILLiad TN: 453217 Call#: 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111 NXSSO.A 1 T68 2016 1-c~ .,.0 ....... Borrower: FHM Location: Atlanta Library North 4 N PROCESS DATE: 1-c -0.> Lending String: 20161003 -+-> *GSU,DLM,TEU,AMH,CSL,EZC,SUS ~~ Patron: ARIEL IFMCharge .......0 Journal Title: The total work of art : r:/). Maxcost: 25.001FM 1-c foundations, articulations, inspirations I 0.> ~ Shipping Address: ......> Volume: Issue: Interlibrary Loans ~ MonthNear: 2016 University of South Florida ~ Pages: 157-182, 259-272 4202 East Fowler Avenue LIB 121 0.> Tampa, Florida 33620 ~ Article Title: The "Translucent (Not: United States -+-> Transparent)" Gesamtglaswerk r./J. Fax: ::r: ro Imprint: New York: Berghahn Books, 2016. (<: ....... NOTICE: THIS MATERIAL MAY BE PROTECTED Ariel: ody or article exchange {_~ BY COPYRIGHT LAW (TITLE 17, U.S. CODE) 0 0.> d ILL Number: 172025970 Or ship via: ARIEL 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 CHAPTERS (""-••.."" The 11 T ranslucent (Not: Transparent)" Gesamtglaswerk JENNY ANGER runo Taut's Glashaus (Glass house, 1914, Figure 8.1) stood on the east Bern bank of the Rhine River, across from the monumental cathedral of Cologne, for just two years. It was accessible to the public for shorter still: a few weeks in the summer of 1914. The outbreak of war-and the need to gar rison soldiers on the German Werkbund's exhibition grounds-might have darkened this temple of light forever. 1 Despite its brief existence, however, the Glashaus contributed to an ideal that aspired to be as enduring and inspi rational as those of its sister temple on the far shore. Following the German tradition of constructing utopian neologisms out of constitutive parts-the Glashaus, for example, or Richard Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art)-I call this ideal the Gesamtglaswerk (total work of glass). -

'We Discharge Ourselves on Both Sides': Vorticism: New Perspectives

‘We discharge ourselves on both sides’: Vorticism: New Perspectives (A symposium convened October 29-30, 2010, at the Nasher Museum of Duke University, Durham, NC) ________ Michael Valdez Moses The Vorticists: Rebel Artists in London and New York, 1914-1918 , the only major exhibition of Vorticist art to be held in the United States since John Quinn and Ezra Pound organized the first American show of Vorticist art at the Penguin Club of New York in 1917, opened at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University on September 30. Curated by Mark Antliff (Professor of Art History at Duke University) and Vivien Greene (Curator of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City), this major exhibition of England’s only ‘home-grown’ avant-garde art movement brings together many of the works exhibited at the three exhibitions organized by the various members of the Vorticist movement during its brief existence: the first Vorticist exhibition at the Doré Gallery in London in 1915, the 1917 Penguin Club exhibition in New York City, and the exhibition of Alvin Langdon Coburn’s ‘Vortographs’ (Vorticist photographs) held at the London Camera Club in 1917. The Vorticists runs at the Nasher through to the 2 nd of January 2010 before moving to the Guggenheim in Venice and then to Tate Britain. The exhibition displays sculpture, paintings, watercolours, collages, prints, drawings, vortographs, books, and journals produced by a group of artists and writers, including Wyndham Lewis, Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, David Bomberg, Lawrence Atkinson, Christopher Nevinson, Edward Wadsworth, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Helen Saunders, Frederick Etchells, Jessica Dismorr, Dorothy Shakespear, William Roberts, and Ezra Pound, who loosely comprised, or were closely associated with, the Vorticist movement that briefly flourished in London and (to a lesser extent) New York in the second decade of the past century. -

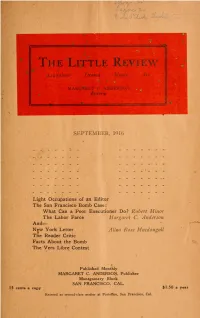

The Little Review, Vol. 3, No. 6

THE LITTLE REVIEW LITERATURE DRAMA MUSIC ART Margaret C. Anderson Editor SEPTEMBER, 1916 Light Occupations of an Editor The San Francisco Bomb Case: What Can a Poor Executioner Do? Robert Minor The Labor Farce Margaret C. Anderson And— New York Letter Allan Ross Macdougall The Reader Critic Facts About the Bomb The Vers Libre Contest Published Monthly MARGARET C. ANDERSON, Publisher Montgomery Block SAN FRANCISCO, CAL. 15 cents a copy $1.50 a year Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, San Francisco. Cal. The Vers Libre Contest The poems published in the Vers Libre Contest are now being considered by the judges. There were two hundred and two poems, thirty-two. of which were re- turned because they were either Shakespearean sonnets or rhymed quatrains or couplets. Manuscripts will be returned as promptly as they are rejected, providing the contestants sent postage. We hope to announce the results in our October issue, and publish the prize poems. —The Contest Editor. IN BOOKS Anything that's Radical MAY be found at McDevitt's Book Omnorium » 1346 Fillmore Street and 2079 Sutter Street San Francisco, California (He Sells The Little Review, Too) THE LITTLE REVIEW VOL III. SEPTEMBER, 1916 NO. 6 The Little Review hopes to become a magazine of Art. The September issue is offered as a Want Ad. Copyright, 1916, by Margaret C. Anderson 2 The Little Reviev . "The other pages will be left blank." The Little Review 3 The Little Review 4 The Little Review 5 The Little Review 6 The Little Review 7 The Little Review 8 The Little Review 9 The Little Review 10 The Little Review 11 The Little Review 14 The Little Review 13 14 The Little Review SHE PRACTICES EIGHTEEN HOURS A DAY AND- BREAKFASTING CONVERTING THE SHERIFF TO ANARCHISM AND VERS LIBRE - TAKES HER MASON AND HAMLIN TO BED WITH HER SUFFERING FOR HUMANITY AT EMMA GOLDMAN'S LECTURES Light occupations of the editor The Little Review 15 GATHERING HER OWN FIRE-WOOO THE STEED on WHICH SHE HAS SWIMMING HER PICTURE TAKEN THE INSECT ON WHICH SHE RIDES while there is nothing to edit. -

NATALIA-GONCHAROVA EN.Pdf

INDEX Press release Fact Sheet Photo Sheet Exhibition Walkthrough A CLOSER LOOK Goncharova and Italy: Controversy, Inspiration, Friendship by Ludovica Sebregondi ‘A spritual autobiography’: Goncharova’s exhibition of 1913 by Evgenia Iliukhina Activities in the exhibition and beyond List of the works Natalia Goncharova A woman of the avant-garde with Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, 28.09.2019–12.01.2020 #NataliaGoncharova This autumn Palazzo Strozzi will present a major retrospective of the leading woman artist of the twentieth- century avant-garde, Natalia Goncharova. Natalia Goncharova will offer visitors a unique opportunity to encounter Natalia Goncharova’s multi-faceted artistic output. A pioneering and radical figure, Goncharova’s work will be presented alongside masterpieces by the celebrated artists who served her either as inspiration or as direct interlocutors, such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni. Natalia Goncharova who was born in the province of Tula in 1881, died in Paris in 1962 was the first women artist of the Russian avant-garde to reach fame internationally. She exhibited in the most important European avant-garde exhibitions of the era, including the Blaue Reiter Munich, the Deutsche Erste Herbstsalon at the Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin and at the post-impressionist exhibition in London. At the forefront of the avant- garde, Goncharova scandalised audiences at home in Moscow when she paraded, in the most elegant area of the city with her face and body painted. Defying public morality, she was also the first woman to exhibit paintings depicting female nudes in Russia, for which she was accused and tried in Russian courts. -

The Little Review and Modernist Salon Culture

MA MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER "Conversations That Fly": The Little Review and Modernist Salon Culture RON LEVY -, Supervisor: Dr. Irene Gammel Reader: Dr. Elizabeth Podnieks The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joint Graduate Program in Communication & Culture Ryerson University - York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada January 2010 Levy 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Irene Gammel for introducing me, through her course CC8938: Modernist Literary Circles: A Cultural Approach, to the Little Review. The personalities that populated the pages of this historically important literary journal practically leapt off the page and attracted me to learn more. Dr. Gammel's enthusiastic and patient guidance made it possible for me to learn about a subject that greatly interests me- the power oftalk - and to challenge myself to reach new levels of research and writing. Unexpectedly, this project also helped me to learn about myself. I found many similarities between my experiences communicating and debating sometimes unpopular beliefs and those of Margaret Anderson, one of the central subjects of this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Podnieks for providing helpful and detailed feedback at short notice, all of which have found their way into this MRP and have further improved this project, as well as for introducing me, through her course CC30: Writing the Self, Reading the Lifo, to theories that relate to the autobiographical genre. Finally, I would like to thank the Joint Graduate Program in Communication and Culture for giving me this incredible experience to step into so many new worlds of thinking.