Claes-Göran Holmberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORDS MADE FLESH Code, Culture, Imagination Florian Cramer

WORDS MADE FLESH Code, Culture, Imagination Florian Cramer Me dia De s ign Re s e arch Pie t Z w art Ins titute ins titute for pos tgraduate s tudie s and re s e arch W ille m de Kooning Acade m y H oge s ch ool Rotte rdam 3 ABSTRACT: Executable code existed centuries before the invention of the computer in magic, Kabbalah, musical composition and exper- imental poetry. These practices are often neglected as a historical pretext of contemporary software culture and electronic arts. Above all, they link computations to a vast speculative imagination that en- compasses art, language, technology, philosophy and religion. These speculations in turn inscribe themselves into the technology. Since even the most simple formalism requires symbols with which it can be expressed, and symbols have cultural connotations, any code is loaded with meaning. This booklet writes a small cultural history of imaginative computation, reconstructing both the obsessive persis- tence and contradictory mutations of the phantasm that symbols turn physical, and words are made flesh. Media Design Research Piet Zwart Institute institute for postgraduate studies and research Willem de Kooning Academy Hogeschool Rotterdam http://www.pzwart.wdka.hro.nl The author wishes to thank Piet Zwart Institute Media Design Research for the fellowship on which this book was written. Editor: Matthew Fuller, additional corrections: T. Peal Typeset by Florian Cramer with LaTeX using the amsbook document class and the Bitstream Charter typeface. Front illustration: Permutation table for the pronounciation of God’s name, from Abraham Abulafia’s Or HaSeichel (The Light of the Intellect), 13th century c 2005 Florian Cramer, Piet Zwart Institute Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of any of the following licenses: (1) the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foun- dation; either version 2 of the License, or any later version. -

Strindberg the M An

STRINDBERG THE M AN GUSTA F UD DGRE N Trans lated from the Swedish HA PP A h L O N U LL P . AXE J V , D Of th e Departm ent of R om ani c L anguages i and Li teratures , Uni ve rs ty of P enns ylvani a BOSTON TH E FOUR S EAS COM PAN Y 1920 INTRODUCTION There are two distinc t ways in which to deal with e ius works e ius : g n and the of g n The old and the new . The old method may be characterized as the descrip tive . It is , generally speaking, negative . It occupies itself mainly with the conscious motives and the external phases of the artist and his life and gives a more or less F literal interpretation of his creation . rom an historical point of view the descriptive method has its own peculiar — value ! from the psycho analytic viewpoint it is less o meritori us , since it adds but little, if anything, to the deeper understanding of the creative mind . The new or interpretative method is based on psychol ’ o . gy It i s positive . It deals exclusively with man s unconscious motivation as the source and main- spring of works of art of whatever kind and independent of time and locality . Thus while the descriptive method accepts u o at its face value the work of geni s , the new or psych analyt ic method penetrates into th e lower strata of the Unconscious in order to find the key to th e cryptic mes sage which is indelibly though always illegibly written r rt in large letters on eve y work of a . -

An Awakening in Sweden: Contemporary Discourses of Swedish Cultural and National Identity

An Awakening in Sweden: Contemporary Discourses of Swedish Cultural and National Identity Kaitlin Elizabeth May Department of Anthropology Undergraduate Honors Thesis University of Colorado Boulder Spring 2018 Thesis Advisor Alison Cool | Department of Anthropology Committee Members Carla Jones | Department of Anthropology Benjamin R. Teitelbaum | Department of Ethnomusicology For my Mothers Grandmothers Mödrar Mormödrar Around the world i Acknowledgements I am very lucky to have so many people who have supported me along this journey. Alison, you are an amazing advisor. You have been so patient and supportive in helping me to figure out this challenge and learn new skills. Thank you for pushing me to think of new ideas and produce more pages. I hope that I can be an Anthropologist like you some day. Carla, thank you for being both my cheerleader and my reality check. For the past year you have given me so much of your time and been supportive, encouraging, and firm. Thank you to Professor Teitelbaum for helping me to prepare my fieldwork and agreeing to be on my committee despite being on paternity leave for the semester. Your support and knowledge has been very influential throughout my research. Tack till min svenska lärare Merete för hennes tålamod och vägledning. Tack till min svenska familj och vänner: Josephine, Ove, Malte, Alice, Cajsa, Tommy, Ann-Britt, Anna, Linnea, Ulla, Niklas, Cajsa, Anders, Marie, Felicia, och Maxe. Jag saknar alla otroligt mycket. Mom and Dad, thank you for supporting me as I switched between academic worlds. You have put so much effort into listening and learning about Anthropology. -

Domestication and Censorship As Guiding Forces in Strindberg's

Translation between Cultures: Domestication and Censorship as Guiding Forces in Strindberg’s Giftas into English Introduction This study will focus on Ellie Schleussner’s translation – Married (1913) – of August Strindberg’s collection of short stories, Giftas I, II, (1884, 1886). It will demonstrate that the original has undergone many changes – some because of the fact that Schleussner’s translation has in turn been based on another translation – Emil Schering’s Heiraten (1910) – rather than on the Swedish original, and some because Schleussner’s translation has been subjected to severe censorship (by whom remains to be seen, to date), which thoroughly undermines Strindberg’s argumentative force. For instance, this force, or power of persuasion, can be seen in the way Strindberg deals with a core concept in Giftas: his naturalist notions that man is an animal (Lagercrantz p. 147). He supports these both by directly stating this very fact in Giftas, but also by using quite explicit sexual descriptions as examples of man being steered by sexual desires, in this way proving his naturalist claims. When these parts are omitted or rewritten, the arguments that Strindberg puts forward to prove his thesis are removed or weakened. The study will also discuss the reasons for the book’s being censored, show how this censorship has been carried out and demonstrate how the German translation has influenced Schleussner’s translation. It will finally argue that although a translation showing the Swedish original much more fidelity was published in 1973 (Mary Sandbach: Getting Married), Schleussner’s translation is still given a platform from which it can exercise an influence on the way Strindberg’s authorship is regarded in the English-speaking world today. -

DER BLAUE REITER Textpuzzle

MDS 3.2 Unterrichtsprojekte in der Sekundarstufe Freiburg vom 29.06. bis 19.07.2014 Ozana Klein, Gabriele Weiß, Alexandra Effe DER BLAUE REITER Textpuzzle Der Blaue Reiter ist die Bezeichnung für eine Künstlergruppe Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts in München. Der Name wurde von Wassily Kandinsky und Franz Marc gewählt. Beide waren Maler und Künstler. Kandinsky hatte bereits 1909 ein Bild … … mit dem Titel „Der Blaue Reiter“ geschaffen. Was die Bezeichnung betrifft, sagte Kandinsky: „Den Namen „Der Blaue Reiter“ erfanden wir am Kaffeetisch in der Gartenlaube in Sindelsdorf. Beide liebten wir Blau: Marc – Pferde und ich – Reiter. So kam der Name … … von selbst.“ Zur Farbe Blau schrieb Kandinsky einmal: „Sie weckt in ihm die Sehnsucht nach Reinem und Übersinnlichem. Es ist die Farbe des Himmels“. August Macke und Franz Marc waren überzeugt, dass jeder Mensch eine innere und eine äußere Erlebniswelt besitzt, die durch die Kunst … … zusammengeführt werden. Außerdem glaubten sie an die Gleichberechtigung aller Kunstformen. Faktisch zählt der Blaue Reiter zum Expressionismus.Kandinsky und Marc gehörten zuerst einer anderen Künstlergruppe an. Sie hieß „Neue Künstlervereinigung München“. Aber besonders Kandinsky hatte … …immer öfter Streit mit den eher traditionell denkenden Mitgliedern der Gruppe wegen seiner sehr abstrakten Malerei und so traten er und Franz Marc 1911 aus. Sie organisierten noch im selben Jahr die erste Blaue-Reiter-Ausstellung, die … … ein großer Erfolg wurde. Die Künstlergruppe „Der Blaue Reiter“ war geboren. Von Anfang an zur Gruppe gehörten auch August Macke und Gabriele Münter, die langjährige Lebensgefährtin von Kandinsky. Sie lebten zusammen in … …Murnau, in der Nähe von Garmisch Partenkirchen im Voralpenland. Ganz in der Nähe, in Sindelsdorf, wohnten Franz und Marie Marc, zu denen sie engen Kontakt hatten. -

Eng1.11.2019 Review Konsthistorisktidskrift RSK

The DOI of your paper is: 10.1080/00233609.2019.1689165, it will be available at the following permanent link: https://doi.org/10.1080/00233609.2019.1689165 . Review of Ludwig Qvarnström (ed.), Swedish Art History: A Selection of Introductory Texts, Lund Studies in Arts and Cultural Sciences 18, 2018. ISBN: 978-91-983690-6-9, 408 p. In his introduction to Swedish Art History: A Selection of Introductory Texts, its editor Ludwig Qvarnström asks, ’Do we need another national art history in these days of globalisation?’ He goes on to reply to his own question by citing the practical needs of, for example, exchange students who have come to study art history at the University of Lund. The history of Swedish art, any more than that of other Nordic countries, is not to be found in so-called general works of art history. For this reason, there has been a focus in all these countries on providing general presentations of the country’s art history, of either broader or more limited scope. English-language versions of these works, however, have been rare. With this in mind, it is understandable that the University of Lund has chosen to publish the book discussed here, especially since the previous general work on Swedish art history in English, A History of Swedish Art by Mereth Lindgren et al. (1987), has been out of print for many years. This new work presents Swedish art history from prehistoric times to the 21st century. The book’s heading, however, specifies that it is a selection of introductory texts by various experts. -

![J Artikel Egil Törnqvist [Artikel]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4403/j-artikel-egil-t%C3%B6rnqvist-artikel-984403.webp)

J Artikel Egil Törnqvist [Artikel]

Egil Törnqvist STRINDBERG THE EUROPEAN ...the intention of this essay is to show that the Swede is a European, with European rights and obligations. In this connection I wish to point out that the Swede, if he wants to grow into a world citizen and tellurian, must give up his petty views concerning the great advantage of being a Swede, which does not mean that he should let another nation eat him up.... (SS 16:143)1 This statement is not, as one might think, a drastic pleading for Sweden's joining of the European Union - before the referendum in November 1994. It is a statement by August Strindberg, made in his essay 'Nationality and Swedishness' more than a hundred years ago. In September 1994 there was a big cultural manifestation in Stockholm called Svenskt Festspel, roughly Swedish Festival. At this event, lasting about ten days, the main theme was "Strindberg and Stockholm". Strindberg was not only celebrated as 'the Swede of the Year', an honour bestowed annually on a prominent Swede living abroad. He was the Stockholmer of the Year. In view of this, it is good to remember that in his own lifetime - except, perhaps, for the very last years - Strindberg was widely regarded as an enemy of his own people and a seducer of Swedish youth. As for Strindberg himself, we should recall that although he always loved Swedish nature - especially the Stockholm archipelago - he frequently attacked the Swedish nation and Swedish mentality. However, Strindberg had not always been critical of his fellow coun- trymen. In the beginning of his career he was, in fact, rather nationalistic. -

Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Författare: Olga Grinchtein © Handledare: Karin Wahlberg Liljeström Påbyggnadskurs (C) i konstvetenskap Vårterminen 2021 ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Olga Grinchtein Titel och undertitel: Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Engelsk titel: Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Handledare Karin Wahlberg Liljeström Ventileringstermin: Höstterm. (år) Vårterm. (år) Sommartermin (år) 2021 The portrait of sculptor emerged in the sixteenth century, where the sitter’s occupation was indicated by his holding a statue. This thesis has focus on portraits of sculptors at the turn of 1900, which have indications of profession. 60 artworks created between 1872 and 1927 are analyzed. The goal of the thesis is to identify new facets that modernism introduced to the portraits of sculptors. The thesis covers the evolution of artistic convention in the depiction of sculptor. The comparison of portraits at the turn of 1900 with portraits of sculptors from previous epochs is included. The thesis is also a contribution to the bibliography of portraits of sculptors. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Karin Wahlberg Liljeström for her help and advice. I also thank Linda Hinners for providing information about Annie Bergman’s portrait of Gertrud Linnea Sprinchorn. I would like to thank my mother for supporting my interest in art history. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... -

In Pursuit of the GENUINE CHRISTIAN IMAGE

In Pursuit of THE GENUINE CHRISTIAN IMAGE Erland Forsberg as a Lutheran Producer of Icons in the Fields of Culture and Religion Juha Malmisalo Academic dissertation To be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Theology of the University of Helsinki, in Auditorium XII in the Main Building of the University, on May 14, 2005, at 10 am. Helsinki 2005 1 In Pursuit of THE GENUINE CHRISTIAN IMAGE Erland Forsberg as a Lutheran Producer of Icons in the Fields of Culture and Religion Juha Malmisalo Helsinki 2005 2 ISBN 952-91-8539-1 (nid.) ISBN 952-10-2414-3 (PDF) University Printing House Helsinki 2005 3 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ................................................................................................................... 6 Preface ..................................................................................................................... 7 1. Encountering Peripheral Cultural Phenomena ......................................... 9 1.1. Forsberg’s Icon Painting in Art Sociological Analysis: Conceptual Issues and Selected Perspectives ............................................................ 9 1.2. An Adaptation of Bourdieu’s Theory of Cultural Fields .......................... 18 1.3. The Pictorial Source Material: Questions of Accessibility and Method .. 23 2. Attempts at a Field-Constitution ................................................................ 30 2.1. Educational, Social, and -

Call#: NXSSO.A1 T68 2016 ~ 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1-C .,.0

ILLiad TN: 453217 Call#: 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111 NXSSO.A 1 T68 2016 1-c~ .,.0 ....... Borrower: FHM Location: Atlanta Library North 4 N PROCESS DATE: 1-c -0.> Lending String: 20161003 -+-> *GSU,DLM,TEU,AMH,CSL,EZC,SUS ~~ Patron: ARIEL IFMCharge .......0 Journal Title: The total work of art : r:/). Maxcost: 25.001FM 1-c foundations, articulations, inspirations I 0.> ~ Shipping Address: ......> Volume: Issue: Interlibrary Loans ~ MonthNear: 2016 University of South Florida ~ Pages: 157-182, 259-272 4202 East Fowler Avenue LIB 121 0.> Tampa, Florida 33620 ~ Article Title: The "Translucent (Not: United States -+-> Transparent)" Gesamtglaswerk r./J. Fax: ::r: ro Imprint: New York: Berghahn Books, 2016. (<: ....... NOTICE: THIS MATERIAL MAY BE PROTECTED Ariel: ody or article exchange {_~ BY COPYRIGHT LAW (TITLE 17, U.S. CODE) 0 0.> d ILL Number: 172025970 Or ship via: ARIEL 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 CHAPTERS (""-••.."" The 11 T ranslucent (Not: Transparent)" Gesamtglaswerk JENNY ANGER runo Taut's Glashaus (Glass house, 1914, Figure 8.1) stood on the east Bern bank of the Rhine River, across from the monumental cathedral of Cologne, for just two years. It was accessible to the public for shorter still: a few weeks in the summer of 1914. The outbreak of war-and the need to gar rison soldiers on the German Werkbund's exhibition grounds-might have darkened this temple of light forever. 1 Despite its brief existence, however, the Glashaus contributed to an ideal that aspired to be as enduring and inspi rational as those of its sister temple on the far shore. Following the German tradition of constructing utopian neologisms out of constitutive parts-the Glashaus, for example, or Richard Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art)-I call this ideal the Gesamtglaswerk (total work of glass). -

NATALIA-GONCHAROVA EN.Pdf

INDEX Press release Fact Sheet Photo Sheet Exhibition Walkthrough A CLOSER LOOK Goncharova and Italy: Controversy, Inspiration, Friendship by Ludovica Sebregondi ‘A spritual autobiography’: Goncharova’s exhibition of 1913 by Evgenia Iliukhina Activities in the exhibition and beyond List of the works Natalia Goncharova A woman of the avant-garde with Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, 28.09.2019–12.01.2020 #NataliaGoncharova This autumn Palazzo Strozzi will present a major retrospective of the leading woman artist of the twentieth- century avant-garde, Natalia Goncharova. Natalia Goncharova will offer visitors a unique opportunity to encounter Natalia Goncharova’s multi-faceted artistic output. A pioneering and radical figure, Goncharova’s work will be presented alongside masterpieces by the celebrated artists who served her either as inspiration or as direct interlocutors, such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni. Natalia Goncharova who was born in the province of Tula in 1881, died in Paris in 1962 was the first women artist of the Russian avant-garde to reach fame internationally. She exhibited in the most important European avant-garde exhibitions of the era, including the Blaue Reiter Munich, the Deutsche Erste Herbstsalon at the Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin and at the post-impressionist exhibition in London. At the forefront of the avant- garde, Goncharova scandalised audiences at home in Moscow when she paraded, in the most elegant area of the city with her face and body painted. Defying public morality, she was also the first woman to exhibit paintings depicting female nudes in Russia, for which she was accused and tried in Russian courts. -

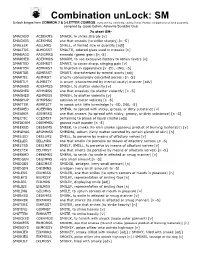

Combination Unlock: SM

Combination unLock: SM Unlock bingos from COMMON 2 & 3-LETTER COMBOS. 7s/8s starting, containing, ending (if any). Plurals / conjugations not listed separately. compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club 7s start SM- SMACKED ACDEKMS SMACK, to strike sharply [v] SMACKER ACEKMRS one that smacks (to strike sharply) [n -S] SMALLER AELLMRS SMALL, of limited size or quantity [adj] SMALTOS ALMOSST SMALTO, colored glass used in mosaics [n] SMARAGD AADGMRS emerald (green gem) [n -S] SMARMED ADEMMRS SMARM, to use excessive flattery to obtain favors [v] SMARTED ADEMRST SMART, to cause sharp, stinging pain [v] SMARTEN AEMNRST to improve in appearance [v -ED, -ING, -S] SMARTER AEMRRST SMART, characterized by mental acuity [adj] SMARTIE AEIMRST smarty (obnoxiously conceited person) [n -S] SMARTLY ALMRSTY in smart (characterized by mental acuity) manner [adv] SMASHED ADEHMSS SMASH, to shatter violently [v] SMASHER AEHMRSS one that smashes (to shatter violently) [n -S] SMASHES AEHMSSS SMASH, to shatter violently [v] SMASHUP AHMPSSU collision of motor vehicles [n -S] SMATTER AEMRSTT to speak with little knowledge [v -ED, ING, -S] SMEARED ADEEMRS SMEAR, to spread with sticky, greasy, or dirty substance [v] SMEARER AEEMRRS one that smears (to spread with sticky, greasy, or dirty substance) [n -S] SMECTIC CCEIMST pertaining to phase of liquid crystal [adj] SMEDDUM DDEMMSU ground malt powder [n -S] SMEEKED DEEEKMS SMEEK, to smoke (to emit smoke (gaseous product of burning materials)) [v] SMEGMAS AEGMMSS SMEGMA, sebum (fatty matter secreted by certain