WORDS MADE FLESH Code, Culture, Imagination Florian Cramer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation

A DIGITAL MEDIA POETICS By MAURO CARASSAI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 1 © 2014 Mauro Carassai 2 To Paola Pizzichini for making me who I am 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my dissertation supervisor Dr. Gregory L. Ulmer, my committee members Dr. Robert B. Ray, Dr. Terry A. Harpold, and Dr. Jack Stenner and all the people who have read sections of this work while in progress and provided invaluable comments, in particular Dr. Adalaide Morris and Dr. N. Katherine Hayles. I also thank my friends and colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 7 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................. 8 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 1 THE POETICS OF ATTENTION: TOWARDS AN ORDINARY DIGITAL PHILOSOPHY ........................................................................................................ 11 The Praxis-Theory Hypothesis of Digitality ............................................................. 11 Mallarmé: Instructions for Use ............................................................................... -

Software Art: Image

NYUAD - Interactive Media Syllabus Software Art: Image NYU Abu Dhabi — Interactive Media SOFTWARE ART: IMAGE IM-UH 2115 Fall 2017 COURSE SYLLABUS Instructor Pierre Depaz ([email protected]) Meeting Time Tuesday — 10:25AM - 1:05PM Thursday — 11:50AM - 1:05PM Classroom C3-153 Office C3-032 Office Hours Open-door policy Credits 2 Class website https://github.com/pierredepaz/software-art-image !1 of !12 NYUAD - Interactive Media Syllabus Software Art: Image This course counts towards the following NYUAD degree requirement: • Multidisciplinary Minors > Interactive Media • Majors > Art and Art History Course Description Although computers only appeared a few decades ago, automation, repetition and process are concepts that have been floating around artists’ minds for almost a century. As machines enabled us to operate on a different scale, they escaped the domain of the purely functional and started to be used, and understood, by artists. The result has been the emergence of code-based art, a relatively new field in the rich tradition of arts history that today acts as an accessible new medium in the practice of visual artists, sculptors, musicians and performers. Software Art: Image is an introduction to the history, theory and practice of computer-aided artistic endeavours in the field of visual arts. This class will focus on the appearance of computers as a new tool for artists to integrate in their artistic practice, how it shaped a specific aesthetic language and what it reveals about technology and art today. We will be elaborating and discussing concepts and paradigms specific to computing platforms, such as system art, generative art, image processing and motion art. -

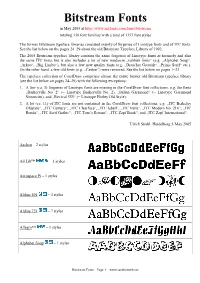

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at Totaling 350 Font Families with a Total of 1357 Font Styles

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at http://www.myfonts.com/fonts/bitstream totaling 350 font families with a total of 1357 font styles The former Bitstream typeface libraries consisted mainly of forgeries of Linotype fonts and of ITC fonts. See the list below on the pages 24–29 about the old Bitstream Typeface Library of 1992. The 2005 Bitstream typeface library contains the same forgeries of Linotype fonts as formerly and also the same ITC fonts, but it also includes a lot of new mediocre „rubbish fonts“ (e.g. „Alphabet Soup“, „Arkeo“, „Big Limbo“), but also a few new quality fonts (e.g. „Drescher Grotesk“, „Prima Serif“ etc.). On the other hand, a few old fonts (e.g. „Caxton“) were removed. See the list below on pages 1–23. The typeface collection of CorelDraw comprises almost the entire former old Bitstream typeface library (see the list below on pages 24–29) with the following exceptions: 1. A few (ca. 3) forgeries of Linotype fonts are missing in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. the fonts „Baskerville No. 2“ (= Linotype Baskerville No. 2), „Italian Garamond“ (= Linotype Garamond Simoncini), and „Revival 555“ (= Linotype Horley Old Style). 2. A lot (ca. 11) of ITC fonts are not contained in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. „ITC Berkeley Oldstyle“, „ITC Century“, „ITC Clearface“, „ITC Isbell“, „ITC Italia“, „ITC Modern No. 216“, „ITC Ronda“, „ITC Serif Gothic“, „ITC Tom’s Roman“, „ITC Zapf Book“, and „ITC Zapf International“. Ulrich Stiehl, Heidelberg 3-May 2005 Aachen – 2 styles Ad Lib™ – 1 styles Aerospace Pi – 1 styles Aldine -

Chapter 13, Using Fonts with X

13 Using Fonts With X Most X clients let you specify the font used to display text in the window, in menus and labels, or in other text fields. For example, you can choose the font used for the text in fvwm menus or in xterm windows. This chapter gives you the information you need to be able to do that. It describes what you need to know to select display fonts for use with X client applications. Some of the topics the chapter covers are: The basic characteristics of a font. The font-naming conventions and the logical font description. The use of wildcards and aliases for simplifying font specification The font search path. The use of a font server for accessing fonts resident on other systems on the network. The utilities available for managing fonts. The use of international fonts and character sets. The use of TrueType fonts. Font technology suffers from a tension between what printers want and what display monitors want. For example, printers have enough intelligence built in these days to know how best to handle outline fonts. Sending a printer a bitmap font bypasses this intelligence and generally produces a lower quality printed page. With a monitor, on the other hand, anything more than bitmapped information is wasted. Also, printers produce more attractive print with variable-width fonts. While this is true for monitors as well, the utility of monospaced fonts usually overrides the aesthetic of variable width for most contexts in which we’re looking at text on a monitor. This chapter is primarily concerned with the use of fonts on the screen. -

Claes-Göran Holmberg

fLaMMan claes-Göran holmberg Precursors swedish avant-garde groups were very late in founding their own magazines. in france and Germany, little magazines had been pub- lished continuously from the romantic era onwards. a magazine was an ideal platform for the consolidation of a new movement in its formative phase. it was a collective thrust at the heart of the enemy: the older generation, the academies, the traditionalists. By showing a united front (through programmatic declarations, manifestos, es- says etc.) you assured the public that you were to be reckoned with. almost every new artist group or current has tried to create a mag- azine to define and promote itself. the first swedish little magazine to embrace the symbolist and decadent movements of fin-de-siècle europe was Med pensel och penna (With paintbrush and pen, 1904-1905), published in Uppsala by the society of “Les quatres diables”, a group of young poets and students engaged in aestheticism and Baudelaire adulation. Mem- bers were the poet and student in slavic languages sigurd agrell (1881-1937), the student and later professor of art history harald Brising (1881-1918), the student of philosophy and later professor of psychology John Landquist (1881-1974), and the author sven Lidman (1882-1960); the poet sigfrid siwertz (1882-1970) also joined the group later. the magazine did not leave any great impact on swedish literature but it helped to spread the Jugend style of illu- stration, the contemporary love-hate relationship with the city and the celebration of the intoxicating powers of beauty and deca- dence. -

P Font-Change Q UV 3

p font•change q UV Version 2015.2 Macros to Change Text & Math fonts in TEX 45 Beautiful Variants 3 Amit Raj Dhawan [email protected] September 2, 2015 This work had been released under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License on July 19, 2010. You are free to Share (to copy, distribute and transmit the work) and to Remix (to adapt the work) provided you follow the Attribution and Share Alike guidelines of the licence. For the full licence text, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode. 4 When I reach the destination, more than I realize that I have realized the goal, I am occupied with the reminiscences of the journey. It strikes to me again and again, ‘‘Isn’t the journey to the goal the real attainment of the goal?’’ In this way even if I miss goal, I still have attained goal. Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 1 Usage .................................................................................. 1 Example ............................................................................... 3 AMS Symbols .......................................................................... 3 Available Weights ...................................................................... 5 Warning ............................................................................... 5 Charter ....................................................................................... 6 Utopia ....................................................................................... -

(2009), No. 2 TEX People: the TUG Interviews Project and Book Karl

196 TUGboat, Volume 30 (2009), No. 2 TEX People: The TUG interviews project 2 The interview method and book Interview subjects are1 chosen based on (a) seeking Karl Berry and David Walden diversity in many dimensions, (b) recommendations from people about who should be interviewed, and Abstract (c) potential interview subjects being willing to be We present the history and evolution of the TUG interviewed. interviews project. We discuss the interviewing pro- The interviews have almost all been done via cess as well as our methods for creating web pages exchange of email using plain text; a couple of ex- and a printed book from the interviews, using m4 as ceptions were done in LATEX. a preprocessor targeting either HTML or LATEX. We For the first several interviews, Dave sent a also describe some business decisions relating to the more or less complete list of questions (once the book. We don't claim great generality for what we interviewee agreed to participate), on the theory that have done, but we hope some of our experience will this would minimize the burden on the interviewee. be educational. However, having a dozen questions to answer at one time proved to be daunting to interviewees. Thus, Dave switched to a process wherein he sent a couple of standard initial questions (namely, \Tell me a 1 Introduction bit about yourself and your history outside of TEX," Dave had two ideas in mind when he suggested (orig- and \How and when did you first get involved with inally to Karl) this interview series in 2004: (a) tech- TEX?"). -

![[' 2. 0 0 7-] Poetics and Rhetorics in Early Modern Germany](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6851/2-0-0-7-poetics-and-rhetorics-in-early-modern-germany-1126851.webp)

[' 2. 0 0 7-] Poetics and Rhetorics in Early Modern Germany

Early Modern German Literature 1350-1700 Edited by Max Reinhart Rochester, New York u.a. CAMDEN HOUSE [' 2. 0 0 7-] Poetics and Rhetorics in Early Modern Germany Joachim Knape ROM ANTIQUIIT ON, REFLECTION ON MEANS of communication - an texts Fin general and poetic texts in particular- brought about two distinct gen res of theoretical texts: rhetorics and poetics. Theoretical knowledge was sys tematized in these two genres for instructional purposes, and its practical applications were debated down to the eighteenth century. At the center of this discussion stood the communicator (or, text producer), armed with pro cedural options and obligations and with the text as his primary instrument of communication. Thus, poeto-rhetorical theory always derived its rules from and reflected the prevailing practice.1 This development began in the fourth century B.C. with Aristotle's Rhetoric and Poetics, which he based an the public communicative practices of the Greek polis in politics, theater, and poetic performance. In the Roman tra dition, rhetorics2 reflectcd the practice of law in thc forum (genus iudiciale), political counsel (genus deliberativum), and communal decisions regarding issues of praise and blame (genus demonstrativum). These comprise the three main speech situations, or cases (genera causarum). The most important the oreticians of rhetoric were Cicero and Quintilian, along with the now unknown author (presumed in the Middle Ages to have been Cicero) of the rhetorics addressed to Herennium. As for poetics, aside from the monumental Ars poet ica ofHorace, Roman literature did not have a particularly rich theoretical tra dition. The Hellenistic poetics On the Sublime by Pseudo-Longinus (first century A.D.) was rediscovered only in the seventeenth century in France and England; it became a key work for modern aesthetics. -

Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick?

AALTO UNIVERSITY School of Science and Technology Faculty of Information and Natural Sciences Department of Media Technology Markku Reunanen Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick? Licentiate Thesis Helsinki, April 23, 2010 Supervisor: Professor Tapio Takala AALTO UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT OF LICENTIATE THESIS School of Science and Technology Faculty of Information and Natural Sciences Department of Media Technology Author Date Markku Reunanen April 23, 2010 Pages 134 Title of thesis Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick? Professorship Professorship code Contents Production T013Z Supervisor Professor Tapio Takala Instructor - This licentiate thesis deals with a worldwide community of hobbyists called the demoscene. The activities of the community in question revolve around real-time multimedia demonstrations known as demos. The historical frame of the study spans from the late 1970s, and the advent of affordable home computers, up to 2009. So far little academic research has been conducted on the topic and the number of other publications is almost equally low. The work done by other researchers is discussed and additional connections are made to other related fields of study such as computer history and media research. The material of the study consists principally of demos, contemporary disk magazines and online sources such as community websites and archives. A general overview of the demoscene and its practices is provided to the reader as a foundation for understanding the more in-depth topics. One chapter is dedicated to the analysis of the artifacts produced by the community and another to the discussion of the computer hardware in relation to the creative aspirations of the community members. -

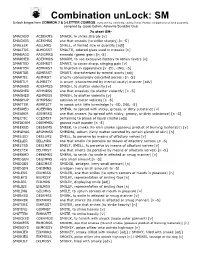

Combination Unlock: SM

Combination unLock: SM Unlock bingos from COMMON 2 & 3-LETTER COMBOS. 7s/8s starting, containing, ending (if any). Plurals / conjugations not listed separately. compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club 7s start SM- SMACKED ACDEKMS SMACK, to strike sharply [v] SMACKER ACEKMRS one that smacks (to strike sharply) [n -S] SMALLER AELLMRS SMALL, of limited size or quantity [adj] SMALTOS ALMOSST SMALTO, colored glass used in mosaics [n] SMARAGD AADGMRS emerald (green gem) [n -S] SMARMED ADEMMRS SMARM, to use excessive flattery to obtain favors [v] SMARTED ADEMRST SMART, to cause sharp, stinging pain [v] SMARTEN AEMNRST to improve in appearance [v -ED, -ING, -S] SMARTER AEMRRST SMART, characterized by mental acuity [adj] SMARTIE AEIMRST smarty (obnoxiously conceited person) [n -S] SMARTLY ALMRSTY in smart (characterized by mental acuity) manner [adv] SMASHED ADEHMSS SMASH, to shatter violently [v] SMASHER AEHMRSS one that smashes (to shatter violently) [n -S] SMASHES AEHMSSS SMASH, to shatter violently [v] SMASHUP AHMPSSU collision of motor vehicles [n -S] SMATTER AEMRSTT to speak with little knowledge [v -ED, ING, -S] SMEARED ADEEMRS SMEAR, to spread with sticky, greasy, or dirty substance [v] SMEARER AEEMRRS one that smears (to spread with sticky, greasy, or dirty substance) [n -S] SMECTIC CCEIMST pertaining to phase of liquid crystal [adj] SMEDDUM DDEMMSU ground malt powder [n -S] SMEEKED DEEEKMS SMEEK, to smoke (to emit smoke (gaseous product of burning materials)) [v] SMEGMAS AEGMMSS SMEGMA, sebum (fatty matter secreted by certain -

Part 1: Historical Settings Reverse

15 PART 1: HISTORICAL SETTINGS REVERSE ENGINEERING MODERNISM WITH THE LAST AVANT-GARDE Dieter Daniels The concept of an avantgarde, disavowed by postmodern theory, is actually more relevant today than ever before, but it has nothing to do with aesthetics. Only social situations, not artworks, qualify as avantgarde. We need access to alternative experience, not merely new ideas, for we know more about our being than we have being for what we know. Today only metadesign satisfi es the original criteria for avantgarde practice. Gene Youngblood01 THE LAST AVANT-GARDE? The case studies analyzed, documented, and contextualized in the Net Pioneers research project provide a representative cross-section of the creation of Net-based art between 1992 and 1997.02 An entire typology of these new art forms developed in just fi ve years. This astonishing dynamic emerged from the particularly intense meeting and interaction of art history and media history: a rapidly developing, international art found itself racing a fast-changing techno-sociological context. As the 1990s drew on, a new browser interface known as the World Wide Web transformed the Internet from a non-public, mostly academic and military medium (with a gray area comprised of nerds and hackers) into a 01 Gene Youngblood, “Metadesign: Towards a Postmodernism of Reconstruction,” abstract for a lecture at Ars Electronica, 1986, http://90.146.8.18/en/archives/festival_archive/festival_catalogs/ festival_artikel.asp?iProjectID=9210. All Internet references in this volume last accessed on November -

Ubermorgen.Com Pressfolder English

1 UBERMORGEN.COM PRESSFOLDER ENGLISH Contact .. UBERMORGEN.COM Favoritenstrasse 26/5 A-1040 Vienna / Austria [email protected] +43 (0)650 930 0061 2 CV HANS BERNHARD (AT/CH/USA) • born 1971 in New Haven, CT, USA • Schools in Switzerland and / USA • University for applied art Vienna, Peter Weibel, Visual Media Creation (Master degree) • Lives and works in Vienna and St. Moritz (Switzerland). Known Aliases: hans_extrem, etoy.HANS, etoy.BRAINHARD, David Arson, Dr. Andreas Bichlbauer, h_e, net_CALLBOY, Luzius A. Bernhard, Andy Bichlbaum, Bart Kessner. Visual Communications, digit Art, Art History and Aesthetics at the University for applied Art Vienna (Austria), UCSD University of California San Diego (Lev Manovich), Art Center College of Design in Pasadena (Peter Lunenfeld and Norman Klein) and at the University Wuppertal (Bazon Brock). Master in fine art from the University of applied Art Vienna. Hans is a professional artist and creative thinker, working on art projects, researching digital networks, exhibiting and travelling the world lecturing at conferences and Universities. Founding member of etoy (the etoy.CORPORATION) and UBERMORGEN.COM. "His style can be described as a digital mix between Andy Kaufman and Jeff Koons, his actions can be seen as underground Barney and early John Lydon, his "Gesamtkunstwerk" has been described as pseudo duchampian and beuyssche and his philosophy is best described in the UBERMORGEN.COM slogan: "It's different because it is fundamentally different!" Bruno Latour Prix Ars Electronica: 1996 Hans Bernhard was awarded a golden Nica for „the digital hijack by etoy“, 2005 with UBERMORGEN.COM he received an Award of Distinction for the [V]ote- auction project [ http://www.vote-auction.net ] and two additional honorary mentions.