Modernism and the Periodical Scene in 1915 and Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fitzgerald in the Late 1910S: War and Women Richard M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2009 Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women Richard M. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Clark, R. (2009). Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/416 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Copyright by Richard M. Clark 2009 FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark Approved July 21, 2009 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda Kinnahan, Ph.D. Greg Barnhisel, Ph.D. Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Dissertation Director) (2nd Reader) ________________________________ ________________________________ Frederick Newberry, Ph.D. Magali Cornier Michael, Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of English (1st Reader) (Chair, Department of English) ________________________________ Christopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda Kinnahan This dissertation analyzes historical and cultural factors that influenced F. -

Letters from the First World War, 1915 Training

Letters from the First World War, 1915 Training Letters from the First World War, 1915 These are some of the many letters sent by staff of the Great Western These are some of the many letters sent by staff of the Great Western Railway Audit office at Paddington who had enlisted to fight in the First World War. Here you will find all the letters and transcripts from this collection that relate to the soldiers' experience of training in England before they were sent abroad. 1915, Training: Contents Training: ‘do you like the photo?’ .............................................................................................. 2 Training: ‘drill before breakfast’ ................................................................................................. 3 Training: ‘no signs of moving’ ..................................................................................................... 6 Training: ‘We are now fully equipped’ ..................................................................................... 7 1 http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Letters from the First World War, 1915 Training Training: ‘do you like the photo?’ Harold George Giles, 17 May 1915, Churn Camp, Oxford, England. Born: 18 May 1898, Joined GWR: 7 August 1912, Joined up for service: 19 March 1915, Regiment: Royal Bucks Hussars, Regiment number:2125; 205745, Rank: Private, Retired: Resigned from Audit office on 9 May 1920 Transcript Dear Mr Jones Just a line to let you know that I’m still alive and am moving to King’s Lynn on Wednesday next. Will write you later. How do you like the photo? Best regards to the office. From, H. Giles 2 http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Letters from the First World War, 1915 Training Training: ‘drill before breakfast’ Arthur Smith, 4 April 1915, France. Born: 8 March 1895, Regiment: Railway Troop, Royal Engineers, Regiment number: 87760, Rank: Lance Corporal Transcript Dear Sir, I have now been out in France a fortnight. -

A Life Transformed: the 1910S

TWO A Life Transformed: The 1910s Not the least significant element of modem political history is contained in the constant growth of individual personality accompanied by the limitation of the State.! Georg Jellinek, 1892 FIRST TRIP TO CHINA AND THE JAPANESE COMMUNITY IN PEKING When Nakae grew bored with working for the South Manchurian Rail way Company, once again his benefactors came to his rescue and found something else for him. Around October 1914, his mother's former boarder, Ts'ao Ju-lin, managed to land him an offer. Ts'ao summoned Nakae to Peking with a one-year contract to work as secretary to Ariga Nagao (1860-1921). Ariga was a professor of international law at Waseda University and had been a friend of Ushikichi's father, although thei; political views diverged sharply. Apparently, years before, Mrs. Nakae out of concern for her wayward son's future had prevailed on the ever grateful Ts'ao to intercede on behalf of Ushikichi if necessary. Nakae received the handsome monthly salary of one hundred yuan for responsibilities neither especially demanding nor explicit. One suspects that he held this sinecure, which might otherwise not have existed, because of his mother's earlier appeal. We know, however, that Nakae spent a great deal of his time in China that year leading what he himself would later refer to as the life of a "profligate villain" (hi5ti5 burai).2 In 1914 Ariga accepted an invitation to serve as an advisor to the gov- "'-------------------- -- 28 A Life Transformed ernment of Yuan Shih-k'ai (1859-1916), which had taken power several years earlier in the young Republic of China. -

The Dial and Transcendentalist Music Criticism” by WESLEY T

The ‘yearnings of the heart to the Infinite’: The Dial and Transcendentalist Music Criticism” by WESLEY T. MOTT “When my hoe tinkled against the stones, that music echoed to the woods and the sky . and I remembered with as much pity as pride, if I remembered at all, my acquaintances who had gone to the city to attend the oratorios.” So wrote contrary Henry Thoreau in “Walden” (1854; [Princeton UP, 1971], p. 159). His literary acquaintances, in fact, had made important contributions to the emergence of music criticism in Boston a decade earlier in the Transcendentalist periodical, the Dial. Published from 1840 to 1844 and edited by Margaret Fuller and Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Dial promised readers in the first issue to give voice to a “new spirit” and to “new views and the dreams of youth,” to aid “the progress of a revolution . united only in a common love of truth, and love of its work” (the Dial, 4 vols. [rpt. New York: Russell & Russell, 1961], 1:1-2. The definitive study is Joel Myerson, The New England Transcendentalists and the Dial: A History of the Magazine and Its Contributors [Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 1980]). Featuring poetry, essays, reviews, and translations on an eclectic range of literary, philosophical, theological, and aesthetic topics, the Dial published only four articles substantially about music: one by John Sullivan Dwight, one by John Francis Tuckerman, and two by Fuller (excluding her lengthy study Romaic and Rhine Ballads [3:137-80] and brief commentary scattered in review articles). Each wrote one installment of an annual Dial feature for 1840-42—a review of the previous winter’s concerts in Boston. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Dial M for Marianne: the Dial’S Refusals of ‘Work in Progress’

GENETIC JOYCE STUDIES – Issue 15 (Spring 2015) Dial M for Marianne: The Dial’s Refusals of ‘Work in Progress’ Ronan Crowley University of Passau Joyce was extremely anxious to introduce his heroine to readers in the United States. Aiming high, I sent her off to the Dial, hoping its editor, Marianne Moore, would find her attractive. I was glad to get word that the Dial had accepted the work, but it turned out that this was a mistake. It had come in when Miss Moore was away, and she was reluctant to publish it. The Dial didn’t back out altogether. I was told, however, that the text would have to be considerably cut down to meet the requirements of the magazine. Now Joyce might have considered the possibility of expanding a work of his, but never, of course, of whittling it down. On the other hand, I couldn’t blame the Dial for its prudence in dealing with a piece so full of rivers that they might have been overflooded at 152 West Thirteenth Street. I was sorry about ‘A.L.P.’s’ failure to make the Dial. Joyce, who was still in Belgium, was not surprised. ‘Why did you not bet with me?’ he wrote. ‘I should have won something.’ He added that he regretted the loss of a ‘strategical position’. Joyce always looked upon his Finnegans Wake as a kind of battle.1 In this characteristically muddled account, Sylvia Beach provides the canonical version of ‘Work in Progress’s’ rejection by the Dial. Implicit in her reference to rivers and the witty image of the flooded Greenwich Village office, explicit in the inclusion of its title is Beach’s conviction that at issue was the ‘Anna Livia Plurabelle’ section (I.8) of the Wake. -

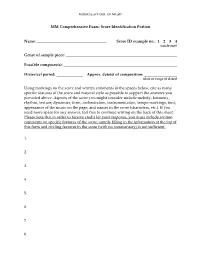

MM Comprehensive Exam: Score Identification Portion Name

MOORES SCHOOL OF MUSIC MM Comprehensive Exam: Score Identification Portion Name: Score ID example no.: 1 2 3 4 (circle one) Genre of sample piece: Possible composer(s): Historical period: Approx. date(s) of composition: (date or range of dates) Using markings on the score and written comments in the spaces below, cite as many specific features of the score and musical style as possible to support the answers you provided above. Aspects of the score you might consider include melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, dynamics, form, orchestration, instrumentation, tempo markings, font, appearance of the music on the page, and names in the score (characters, etc.). If you need more space for any answer, feel free to continue writing on the back of this sheet. Please note that in order to receive credit for your response, you must include written comments on specific features of the score; simply filling in the information at the top of this form and circling features in the score (with no commentary) is not sufficient. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Andrew Davis. rev. Nov 2009. General information on preparing for a comprehensive exam in music (geared especially toward answering questions in music theory and/or discussing unidentified scores): Comprehensive exams (especially music theory portions, and to some extent score identification portions, if applicable) ask you to focus on broad theoretical and/or stylistic topics that you're expected to know as a literate musician with a graduate degree in music. For example, in the course of the exam you might -

The Waste Land by T

The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot Copyright Notice ©1998−2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. ©2007 eNotes.com LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. For complete copyright information on these eNotes please visit: http://www.enotes.com/waste−land/copyright Table of Contents 1. The Waste Land: Introduction 2. Text of the Poem 3. T. S. Eliot Biography 4. Summary 5. Themes 6. Style 7. Historical Context 8. Critical Overview 9. Essays and Criticism 10. Topics for Further Study 11. Media Adaptations 12. What Do I Read Next? 13. Bibliography and Further Reading 14. Copyright Introduction Because of his wide−ranging contributions to poetry, criticism, prose, and drama, some critics consider Thomas Sterns Eliot one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. The Waste Land can arguably be cited as his most influential work. When Eliot published this complex poem in 1922—first in his own literary magazine Criterion, then a month later in wider circulation in the Dial— it set off a critical firestorm in the literary world. The work is commonly regarded as one of the seminal works of modernist literature. Indeed, when many critics saw the poem for the first time, it seemed too modern. -

The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2008 The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading Emily A. Cope University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cope, Emily A., "The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/348 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Emily A. Cope entitled "The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Dawn Coleman, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Janet Atwill, Martin Griffin Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Emily Ann Cope entitled “The Dial and the Transcendentalist Theory of Reading.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Orpheu Et Al. Modernism, Women, and the War

Orpheu et al. Modernism, Women, and the War M. Irene Ramalho-Santos* Keywords Little magazines, Poetry, Modernism, The Great War, Society, Sexual mores. Abstract The article takes off from Orpheu, the little magazine at the origin of Portuguese modernism, to reflect, from a comparative perspective, on the development of modernist poetry in the context of the Great War and the social changes evolving during the first decades of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic. Palavras-chave “Little magazines,” Poesia, Modernismo, A Grande Guerra, Sociedade, Costumes sexuais. Resumo O artigo parte de Orpheu, a revista que dá origem ao modernismo português, para reflectir, numa perspectiva comparada, soBre o desenvolvimento da poesia modernista no contexto da Grande Guerra e das mudanças sociais emergentes nas primeiras décadas do século XX dos dois lados do Atlântico. * Universidade de CoimBra; University of Wisconsin-Madison. Ramalho Santos Orpheu et al. It is frequently repeated in the relevant scholarship that Western literary and artistic modernism started in little magazines.1 The useful online Modernist Journals Project (Brown University / Tulsa University), dealing so far only with American and British magazines, uses as its epigraph the much quoted phrase: “modernism began in the magazines”, see SCHOLES and WULFMAN (2010) and BROOKER and THACKER (2009-2013). With two issues published in 1915 and a third one stopped that same year in the galley proofs for lack of funding, the Portuguese little magazine Orpheu inaugurated modernism in Portugal pretty much at the same time as all the other major little magazines in Europe and the United States. This is interesting, given the proverbial belatedness of Portuguese accomplishments, and no less interesting the fact that, like everywhere else, Orpheu was followed, in Portugal as well, By a number of other little magazines.