Aspects of Jazz and Classical Music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Orchestra Society THOMAS SCHERMAN, Music Director

l (b~{ ozoog BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC The Little Orchestra Society THOMAS SCHERMAN, Music Director ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION SERIES-SEASON 1968-69 Second Concert Sunday Afternoon, December 15, 1968 at 2:30P.M. HERBERT BARRETT, Manager ALVARO CASSUTO, Guest Conductor RUGGIERO RICCI, Violinist WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Symphony No. 34 inC major, K. 338 I Allegro vivace II Andante di molto III Allegro vivace PAUL HINDEMITH Kammermusik No. 4 for Violin and Chamber Orchestra, Op. 36, No.3 I Signal. Breite majestatische Halbe- 11 Sehr lebhaft III Nachtstiick. Massig schnelle Achtel IV Lebhafte Viertel- V So Schnell, wie moglich RUGGIERO RICCI, Soloist INTERMISSION JOSEF ALEXANDER Duo Concertante for Trombone, String Orchestra, and Percussion (World premiere) JOHN GRAMM, Trombone WALLACE DEYERLE, Percussion JOLY BRAGA SANTOS Sinfonietta for String Orchestra (American premiere) I Adagi~Allegro II Adagio III Allegro ben marcato, rna non tropp~ Larg~Tempo I ROBERT SCHUMANN Overture, Scherzo, and Finale Op. 52 I Overture: Andante con mot~Allegro II Scherzo: Vivo Ill Finale: Allegro molto vivace NOTES ON THE PROGRAM by BERNARD JACOBSON Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 34 in C maJor, K. 338 (17 5 6-1791 ) I Allegro Vlvace II Andante di molto III A /legro vivace Mozart's 34th Symphony was the last one he wrote m Salzburg. It was composed in August, 1780, and like its predecessor by a year-No. 33 m B flat major, K. 319-was ongmally performed v.1th only three movements. In the case of No 34, however, the composer's autograph core contams, between the first two movements, the beginning of a mmuet Th1s was subsequently deleted. -

Fitzgerald in the Late 1910S: War and Women Richard M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2009 Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women Richard M. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Clark, R. (2009). Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/416 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Copyright by Richard M. Clark 2009 FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark Approved July 21, 2009 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda Kinnahan, Ph.D. Greg Barnhisel, Ph.D. Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Dissertation Director) (2nd Reader) ________________________________ ________________________________ Frederick Newberry, Ph.D. Magali Cornier Michael, Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of English (1st Reader) (Chair, Department of English) ________________________________ Christopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda Kinnahan This dissertation analyzes historical and cultural factors that influenced F. -

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC of the Manatee BERNARD

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER TROY1765 PIANO MUSIC OF Seven Preludes for Piano (1975) 15 The Manatee [2:36] 16 Stridin’ Thru The Olde Towne 1 Prelude [2:40] 2 Cello [2:47] During Prohibition In Search Of A Drink [2:42] 3 All Over The Piano [1:21] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 4 Ships Passing [4:12] (2014) BERNARD HOFFER 5 Prelude [1:24] Events & Excursions for Two Pianos 6 Calypso [3:52] 17 Big Bang Theory [3:15] 7 Franz Liszt Plays Ragtime [3:28] 18 Running [3:19] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 19 Wexford Noon [2:29] 20 Reverberations [3:12] Nine New Preludes for Piano (2016) 21 On The I-93 [2:23] Randall Hodgkinson & Leslie Amper, pianos 8 Undulating Phantoms [1:08] BERNARD HOFFER 9 A Walk In The Park [2:39] 10 Speed Chess [2:17] 22 Naked (2010) [5:05] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 11 Valse Sentimental [3:30] 12 Rabbits [1:06] Total Time = 60:03 13 Spirals [1:40] 14 Canon Inverso [1:44] PIANO MUSIC OF TROY1765 WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2019 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

Part 2 of Selected Discography

Part 2 of Selected Discography Milt Hinton Solos Compiled by Ed Berger (1949-2017) - Librarian, journalist, music producer, photographer, historian, and former Associate Director, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. This is a chronological list of representative solos by Hinton as a sideman in a variety of settings throughout his career. Although not definitive, Milt was such a consistent soloist that one could cite many other equally accomplished performances. In some cases, particularly from the 1930s when bass solos were relatively rare, the recordings listed contain prominent bass accompaniment. November 4, 1930, Chicago Tiny Parham “Squeeze Me” (first Hinton recording, on tuba) 78: Recorded for Victor, unissued CD: Timeless CBC1022 (Tiny Parham, 1928–1930) January–March 1933, Hollywood Eddie South “Throw a Little Salt on the Bluebird’s Tail” (vocal) “Goofus” CD: Jazz Oracle BDW8054 (Eddie South and His International Orchestra: The Cheloni Broadcast Transcriptions) May 3, 1933, Chicago Eddie South “Old Man Harlem” (vocal) 78: Victor 24324 CD: Classics 707 (Eddie South, 1923–1937) June 12, 1933, Chicago Eddie South “My, Oh My” (slap bass) 78: Victor 24343 CD: Classics 707 (Eddie South, 1923-1937) March 3, 1937 Cab Calloway “Congo” 78: Variety 593 CD: Classics 554 (Cab Calloway, 1934–1937) January 26, 1938 Cab Calloway “I Like Music” (brief solo, slap bass) 78: Vocalion 3995 CD: Classics 568 (Cab Calloway, 1937–1938) August 30, 1939 Cab Calloway “Pluckin’ the Bass” (solo feature —slap bass) 78: Vocalion 5406 CD: Classics -

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42Nd ANNUAL

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42nd ANNUAL JUNE 2019 DOWNBEAT 95 JeJenna McLean, from the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, is the Graduate College Wininner in the Vocal Jazz Soloist category. She is also the recipient of an Outstanding Arrangement honor. 42nd Student Music Awards WELCOME TO THE 42nd ANNUAL DOWNBEAT STUDENT MUSIC AWARDS The UNT Jazz Singers from the University of North Texas in Denton are a winner in the Graduate College division of the Large Vocal Jazz Ensemble category. WELCOME TO THE FUTURE. WE’RE PROUD after year. (The same is true for certain junior to present the results of the 42nd Annual high schools, high schools and after-school DownBeat Student Music Awards (SMAs). In programs.) Such sustained success cannot be this section of the magazine, you will read the attributed to the work of one visionary pro- 102 | JAZZ INSTRUMENTAL SOLOIST names and see the photos of some of the finest gram director or one great teacher. Ongoing young musicians on the planet. success on this scale results from the collec- 108 | LARGE JAZZ ENSEMBLE Some of these youngsters are on the path tive efforts of faculty members who perpetu- to becoming the jazz stars and/or jazz edu- ally nurture a culture of excellence. 116 | VOCAL JAZZ SOLOIST cators of tomorrow. (New music I’m cur- DownBeat reached out to Dana Landry, rently enjoying includes the 2019 albums by director of jazz studies at the University of 124 | BLUES/POP/ROCK GROUP Norah Jones, Brad Mehldau, Chris Potter and Northern Colorado, to inquire about the keys 132 | JAZZ ARRANGEMENT Kendrick Scott—all former SMA competitors.) to building an atmosphere of excellence. -

Cedille Records CDR 90000 066 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 AFRICAN HERITAGE SYMPHONIC SERIES • VOLUME III WORLD PREMIERE RECORDINGS 1 MICHAEL ABELS (B

Cedille Records CDR 90000 066 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 AFRICAN HERITAGE SYMPHONIC SERIES • VOLUME III WORLD PREMIERE RECORDINGS 1 MICHAEL ABELS (b. 1962): Global Warming (1990) (8:18) DAVID BAKER (b. 1931): Cello Concerto (1975) (19:56) 2 I. Fast (6:22) 3 II. Slow à la recitative (7:17) 4 III. Fast (6:09) Katinka Kleijn, cello soloist 5 WILLIAM BANFIELD (b. 1961): Essay for Orchestra (1994) (10:33) COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON (b. 1932) Generations: Sinfonietta No. 2 for Strings (1996) (19:31) 6 I. Misterioso — Allegro (6:13) 8 III. Alla Burletta (2:04) 7 II. Alla sarabande (5:35) 9 IV. Allegro vivace (5:28) CHICAGO SINFONIETTA / PAUL FREEMAN, CONDUCTOR TT: (58:45) Sara Lee Foundation is the exclusive corporate sponsor for African Heritage Symphonic Series, Volume III This recording is also made possible in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts & The Aaron Copland Fund for Music Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by contributions and grants from individuals, foundations, corporations, and government agencies including the Alpha- wood Foundation, the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs (CityArts III Grant), and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 PROGRAM NOTES by dominique-rené de lerma The quartet of composers represented here have a par- cultures, and decided to write a piece that celebrates ticular distinction in common: Each displays remarkable these common threads as well as the sudden improve- stylistic versatility, working not just in concert idioms, but ment in international relations that was occurring.” The also in film music, gospel music, and jazz. -

New and Lesser Known Works for Saxophone Quartet: a Recording

New and Lesser Known Works for Saxophone Quartet: A Recording, Performance Guide, and Composer Interviews by Woodrow Chenoweth A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Christopher Creviston, Chair Joshua Gardner Michael Kocour Ted Solis ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2019 ABSTRACT This project includes composer biographies, program notes, performance guides, composer questionnaires, and recordings of five new and lesser known works for saxophone quartet. Three of the compositions are new pieces commissioned by Woody Chenoweth for the Midwest-based saxophone quartet, The Shredtet. The other two pieces include a newer work for saxophone quartet never recorded in its final version, as well as an unpublished arrangement of a progressive rock masterpiece. The members of The Shredtet include saxophonists Woody Chenoweth, Jonathan Brink, Samuel Lana, and Austin Atkinson. The principal component of this project is a recording of each work, featuring the author and The Shredtet. The first piece, Sax Quartet No. 2 (2018), was commissioned for The Shredtet and written by Frank Nawrot (b. 1989). The second piece, also commissioned for The Shredtet, was written by Dan Puccio (b. 1980) and titled, Scherzos for Saxophone Quartet (2018). The third original work for The Shredtet, Rhythm and Tone Study No. 3 (2018), was composed by Josh Bennett (b. 1982). The fourth piece, Fragments of a Narrative , was written by Ben Stevenson (b. 1979) in 2014 and revised in 2016, and was selected as runner-up in the Donald Sinta Quartet’s 2016 National Composition Competition. -

Conflict, Vagueness, Dissolution : Challenges to Meter In

Online publications of the Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung/ German Society for Popular Music Studies e. V. Ed. by Eva Krisper, Eva Schuck, Ralf von Appen and André Doehring w w w . gf pm - samples.de/Samples16/ pf l e i de r e r . pdf Volume 16 (2018) - Version of 6/28/2018 CONFLICT, VAGUENESS, DISSOLUTION. CHALLENGES TO METER I N CONTEMPORARY JAZZ Martin Pfleiderer Music's temporal structure is organised at various time levels. While the level of musical form corresponds to longer time distances, rhythm refers to the small scale temporal structuring of sonic events. Musical rhythm can be de- fined as the time structure of a gestalt-like sequence of musical sounds that have differing degrees of salience or accentuation and lie within a time frame of a few seconds (Pfleiderer 2006: 154ff.). Since an event can be accentuated in various ways, e.g. loudness, duration, position within a musical phrase and within its pitch contour, relation to the harmonic and metric context, timbre etc., there are many ways of shaping and perceiving sound sequences as rhythms. Moreover, the temporal structure of what we listen to actively shapes our expectations of what we are going to hear—within a certain piece of music as well as within a musical style. Furthermore, musical expectations and anticipations seem to be a basis and prerequisite for surprise and enjoy- ment in music—with regard to form, harmony, and rhythm (Huron 2006). Expectations that are built up in regard to small scale temporal regulari- ties of sound sequences are widely supported and enhanced by our atten- tional, cognitive and bodily entrainment to music and are commonly referred to as musical meter. -

Program Board Needs 'In-Put' Don Ellis at A.H.S

November 3. 1972 SISKIYOU Page 7 Program Board S.OC. has 28 in Who's Who “Who’s Who Among is required to submit his or her Hagen, Isabelle Rachel Hayley, American Universities and own biographical data” said David Merritt Hennan, Gregory needs 'in-put' Colleges” has chosen 28 out-, Fellers. Boyd Keylock, Lindall Wayne standing SO. .C seniors to be The. student's name and Lawless, Nola Sue McMinimy, listed this year, according to biographical data are then diverse. The only music Michael Anthony Mendibure, The Concert Lecture Dr. Alvin Fellers, dean of published in the directory John P. Newell, Joey Yee-Cho Committee consists of nine students represented is classical. Why students. entitled ‘Who’s Who among not a variety of concerts of Ngan, Macceo Pettis, Robert and seven faculty. Five of the students in American William Polski, Janet Lee the students must be present at lesser known musicians of low “First published in 1934, this Universities and Colleges.” Prickett, Vikki Lanette a meeting before a vote on cost? There are no literary directory has appeared Those selected for the next figures involved. What about nick,Ren William Neil Standley, eventan can be taken. This is annually—a unique institution edition are the following 28 Elizabeth Ann Stewart, David that students can maintain a Richard Brautigan, or a film which now includes thousands Seniors: Carolyn Marie producer, or science fiction E. Thompson, Sharann Mikie majority in a committee that of listings from over 1,000 Ainsworth, Dale Barnhart, Judy Turner, George Chor-Sik Wong, includes faculty input and writer like Asminov? Or your schools, in all 50 states, the Lynn Brown, Vance LeLand particular favorite? There is no and Charles Merritt Barker” swing power involving student District of Columbia and Burghard, Marilyn Marie “These Seniors represent the drama or modern dance. -

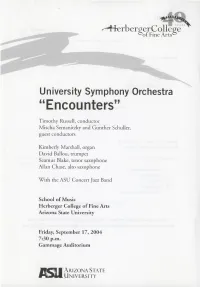

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

The Exotic Rhythms of Don Ellis a Dissertation Submitted to the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University in Partial Fu

THE EXOTIC RHYTHMS OF DON ELLIS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PEABODY INSTITUTE OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS BY SEAN P. FENLON MAY 25, 2002 © Copyright 2002 Sean P. Fenlon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Fenlon, Sean P. The Exotic Rhythms of Don Ellis. Diss. The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, 2002. This dissertation examines the rhythmic innovations of jazz musician and composer Don Ellis (1934-1978), both in Ellis’s theory and in his musical practice. It begins with a brief biographical overview of Ellis and his musical development. It then explores the historical development of jazz rhythms and meters, with special attention to Dave Brubeck and Stan Kenton, Ellis’s predecessors in the use of “exotic” rhythms. Three documents that Ellis wrote about his rhythmic theories are analyzed: “An Introduction to Indian Music for the Jazz Musician” (1965), The New Rhythm Book (1972), and Rhythm (c. 1973). Based on these sources a general framework is proposed that encompasses Ellis’s important concepts and innovations in rhythms. This framework is applied in a narrative analysis of “Strawberry Soup” (1971), one of Don Ellis’s most rhythmically-complex and also most-popular compositions. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to extend my heartfelt thanks to my dissertation advisor, Dr. John Spitzer, and other members of the Peabody staff that have endured my extended effort in completing this dissertation. Also, a special thanks goes out to Dr. H. Gene Griswold for his support during the early years of my music studies. -

A Life Transformed: the 1910S

TWO A Life Transformed: The 1910s Not the least significant element of modem political history is contained in the constant growth of individual personality accompanied by the limitation of the State.! Georg Jellinek, 1892 FIRST TRIP TO CHINA AND THE JAPANESE COMMUNITY IN PEKING When Nakae grew bored with working for the South Manchurian Rail way Company, once again his benefactors came to his rescue and found something else for him. Around October 1914, his mother's former boarder, Ts'ao Ju-lin, managed to land him an offer. Ts'ao summoned Nakae to Peking with a one-year contract to work as secretary to Ariga Nagao (1860-1921). Ariga was a professor of international law at Waseda University and had been a friend of Ushikichi's father, although thei; political views diverged sharply. Apparently, years before, Mrs. Nakae out of concern for her wayward son's future had prevailed on the ever grateful Ts'ao to intercede on behalf of Ushikichi if necessary. Nakae received the handsome monthly salary of one hundred yuan for responsibilities neither especially demanding nor explicit. One suspects that he held this sinecure, which might otherwise not have existed, because of his mother's earlier appeal. We know, however, that Nakae spent a great deal of his time in China that year leading what he himself would later refer to as the life of a "profligate villain" (hi5ti5 burai).2 In 1914 Ariga accepted an invitation to serve as an advisor to the gov- "'-------------------- -- 28 A Life Transformed ernment of Yuan Shih-k'ai (1859-1916), which had taken power several years earlier in the young Republic of China.