A Life Transformed: the 1910S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fitzgerald in the Late 1910S: War and Women Richard M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2009 Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women Richard M. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Clark, R. (2009). Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/416 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Copyright by Richard M. Clark 2009 FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark Approved July 21, 2009 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda Kinnahan, Ph.D. Greg Barnhisel, Ph.D. Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Dissertation Director) (2nd Reader) ________________________________ ________________________________ Frederick Newberry, Ph.D. Magali Cornier Michael, Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of English (1st Reader) (Chair, Department of English) ________________________________ Christopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda Kinnahan This dissertation analyzes historical and cultural factors that influenced F. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

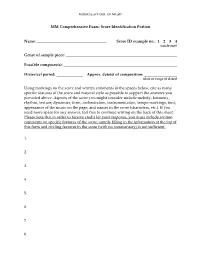

MM Comprehensive Exam: Score Identification Portion Name

MOORES SCHOOL OF MUSIC MM Comprehensive Exam: Score Identification Portion Name: Score ID example no.: 1 2 3 4 (circle one) Genre of sample piece: Possible composer(s): Historical period: Approx. date(s) of composition: (date or range of dates) Using markings on the score and written comments in the spaces below, cite as many specific features of the score and musical style as possible to support the answers you provided above. Aspects of the score you might consider include melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, dynamics, form, orchestration, instrumentation, tempo markings, font, appearance of the music on the page, and names in the score (characters, etc.). If you need more space for any answer, feel free to continue writing on the back of this sheet. Please note that in order to receive credit for your response, you must include written comments on specific features of the score; simply filling in the information at the top of this form and circling features in the score (with no commentary) is not sufficient. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Andrew Davis. rev. Nov 2009. General information on preparing for a comprehensive exam in music (geared especially toward answering questions in music theory and/or discussing unidentified scores): Comprehensive exams (especially music theory portions, and to some extent score identification portions, if applicable) ask you to focus on broad theoretical and/or stylistic topics that you're expected to know as a literate musician with a graduate degree in music. For example, in the course of the exam you might -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Aspects of Jazz and Classical Music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini Heather Koren Pinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pinson, Heather Koren, "Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 2589. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2589 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPECTS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC IN DAVID N. BAKER’S ETHNIC VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF PAGANINI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The School of Music by Heather Koren Pinson B.A., Samford University, 1998 August 2002 Table of Contents ABSTRACT . .. iii INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER 1. THE CONFLUENCE OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC 2 CHAPTER 2. ASPECTS OF MODELING . 15 CHAPTER 3. JAZZ INFLUENCES . 25 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 48 APPENDIX 1. CHORD SYMBOLS USED IN JAZZ ANALYSIS . 53 APPENDIX 2 . PERMISSION TO USE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL . 54 VITA . 55 ii Abstract David Baker’s Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini (1976) for violin and piano bring together stylistic elements of jazz and classical music, a synthesis for which Gunther Schuller in 1957 coined the term “third stream.” In regard to classical aspects, Baker’s work is modeled on Nicolò Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice for Solo Violin, itself a theme and variations. -

The Decline and Fall of the European Film Industry: Sunk Costs, Market Size and Market Structure, 1890-1927

Working Paper No. 70/03 The Decline and Fall of the European Film Industry: Sunk Costs, Market Size and Market Structure, 1890-1927 Gerben Bakker © Gerben Bakker Department of Economic History London School of Economics February 2003 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0)20 7955 6482 Fax: +44 (0)20 7955 7730 Working Paper No. 70/03 The Decline and Fall of the European Film Industry: Sunk Costs, Market Size and Market Structure, 1890-1927 Gerben Bakker © Gerben Bakker Department of Economic History London School of Economics February 2003 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0)20 7955 6482 Fax: +44 (0)20 7955 7730 Table of Contents Acknowledgements_______________________________________________2 Abstract________________________________________________________3 1. Introduction___________________________________________________4 2. The puzzle____________________________________________________7 3. Theory______________________________________________________16 4. The mechanics of the escalation phase _____________________________21 4.1 The increase in sunk costs______________________________________21 4.2 The process of discovering the escalation parameter _________________29 4.3 Firm strategies_______________________________________________35 5. Market structure ______________________________________________47 6. The failure to catch up _________________________________________54 7. Conclusion __________________________________________________63 -

Suffrage During the Pandemics of 1918 and 2020

IdeAs Idées d'Amériques 16 | 2020 Les marges créatrices : intellectuel.le.s afro- descendant.e.s et indigènes aux Amériques, XIX-XXe siècle Suffrage during the Pandemics of 1918 and 2020 Allison K. Lange Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/9432 DOI: 10.4000/ideas.9432 ISSN: 1950-5701 Publisher Institut des Amériques Electronic reference Allison K. Lange, « Suffrage during the Pandemics of 1918 and 2020 », IdeAs [Online], 16 | 2020, Online since 01 October 2020, connection on 18 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/ 9432 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ideas.9432 This text was automatically generated on 18 October 2020. IdeAs – Idées d’Amériques est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Suffrage during the Pandemics of 1918 and 2020 1 Suffrage during the Pandemics of 1918 and 2020 Allison K. Lange 1 In October 1918, a suffragist named Florence Huberwald declared to the New Orleans Times-Picayune: “Everything conspires against woman suffrage” (“Influenza,” 1918). That month, she and many other activists watched as the number of flu cases in the United States rose. When I encountered her quote in April 2020, I could relate to her experience in a way that I could not have imagined a few months before. Huberwald had plans, and she saw them collapsing. I, too, had plans, but fellow scholars, museums, historical societies, and numerous other organizations slowly realized that the events we had organized to mark the 19th Amendment’s centennial needed to be changed. -

The Roaring 1900S, 1910S, and 1920S DJ Script Good Evening, Ladies and Gentlemen

The Roaring 1900s, 1910s, and 1920s DJ script Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. I am happy to speak to all the listeners out there who own the wonderful invention called the radio. Tonight we’ll be listening to a few pieces of popular music from the early 20th century, including the 1900s, 1910s, and 1920s. Let’s begin! The first song you’ll hear is a good example of ragtime music. Ragtime was popular in the 1900s, and this song is the most famous example. It was written in 1902 by an African American man named Scott Joplin. The song is called The Entertainer and it is written for a solo piano. Here’s The Entertainer by Scott Joplin. *listen to “The Entertainer” The next song is by a very famous songwriter named Irving Berlin. He is perhaps the most prolific American songwriter of all time, which means he’s written more popular songs than any other American. This song was inspired by ragtime music and became a hit in 1911. Please enjoy this recording of Alexander’s Ragtime Band by Irving Berlin. *listen to “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” The most important and influential style of music to come out of this time period came from the 1920s. The style is called blues. Blues began as music sung by slaves in the southern United States in the 1800’s and evolved to a sophisticated form of popular music. W.C. Handy, known as the “Father of the Blues” wrote this next song, St. Louis Blues. *listen to“St. Louis Blues” The next popular style of music to emerge in the 1910s was called Dixieland Jazz. -

Special Libraries, September 1917 Special Libraries Association

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1917 Special Libraries, 1910s 9-1-1917 Special Libraries, September 1917 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1917 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, September 1917" (1917). Special Libraries, 1917. Book 7. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1917/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1910s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1917 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Special Libraries - -- Vol. 8 SEPTEMBER, 1917 No. 7 - -- - .. - --. - - -- -- - Minutes of the Special Libraries Association Louisville, Kentucky, June 25 and 20, 1917. FIRST SESSION Ethel &I. Jol~nson, 1ibr:~ri:uri of tlic WCII~CII'A Eclucationnl nntl Incluslrinl Union, 13osl011. June 25, 1917, A.M. Thc ninth nnnuiil rncc!t.ing of thts Spccial THIRD SESSION Librnrics Association was callctl to ordrr by tllc lJrcsidcnt, Dr. C. C. lVill~:unson,on the tcntll June 26, 1917, P.M. floor of tlic Bcclb:wli, :it 9.30 A.M. (1, 7 I hc BO-callcd libral MI'S ~.td~SOVIIIC~'~ by Mntlhc\v Srusli, Prrsitlent 01 thc 13oston Elc- valccl 12niJwny was rc:d hy Mr. Lcc of Boston. Dr. Paul T-I. Nysl.ro111 ol the 1ntrrn:~l.ionnl M:~gaxii~cCornpnny prrsentc!tl nn unusu:d con- tributm~ of spcci:d 1ihr:n.y 11l.cmturc In 111s iultlr~s"Tllc busincss library :IS :un inwstment, " 'I'licn lollowcd the prcsulontid ~ltldrrsshy Dr W~ll~i~~nson,printed in this ISBI~Oof SPECIAL Lma~itrm. -

The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917

United States Cryptologic History The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917 Special Series | Volume 7 Center for Cryptologic History David Hatch is technical director of the Center for Cryptologic History (CCH) and is also the NSA Historian. He has worked in the CCH since 1990. From October 1988 to February 1990, he was a legislative staff officer in the NSA Legislative Affairs Office. Previously, he served as a Congressional Fellow. He earned a B.A. degree in East Asian languages and literature and an M.A. in East Asian studies, both from Indiana University at Bloomington. Dr. Hatch holds a Ph.D. in international relations from American University. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: Before and during World War I, the United States Army maintained intercept sites along the Mexican border to monitor the Mexican Revolution. Many of the intercept sites consisted of radio-mounted trucks, known as Radio Tractor Units (RTUs). Here, the staff of RTU 33, commanded by Lieutenant Main, on left, pose for a photograph on the US-Mexican border (n.d.). United States Cryptologic History Special Series | Volume 7 The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917 David A. -

Federal Reserve Bulletin November 1915

FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN ISSUED BY THE FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD AT WASHINGTON NOVEMBER, 1915 WASHINGTON GOVEENMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD. EX OFFICIO MEMBERS, CHARLES S. HAMLIN, Governor. FREDERIC A. DELANO, Vice Governor. WILLIAM G. MCADOO, PAUL AI. WARBURG. Secretary of the Treasury? W. P. G. HARDING. Chairman. ADOLPH C. MILLER. JOHN SKELTON WILLIAMS, Comptroller of the Currency. H. PARKER WILLIS, Secretary. SHERMAN ALLEN, Assistant Secretary. Af. C, ELLIOTT, Counsel. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis SUBSCRIPTION PRICE OF BULLETIN. The Federal Reserve Bulletin is distributed without charge to member banks of the system and to the officers and directors of Federal Reserve Banks. In sending the Bulletin to others the Board feels that a subscription should be required. It has accordingly fixed a subscription price of $2 per annum. Single copies will be sold at 20 cents. Foreign postage should be added when it will be required. Remittances should be made to the Federal Reserve Board. m Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page. Work of the Federal Reserve Board 345 Service to member banks 346 Foreign agencies * 348 Earnings and expenditures of Federal Reserve Banks 349 Interdistrict movement of Federal Reserve notes 351 Addresss by Hon. P. M. Warburg 352 Franking of Federal Reserve notes 355 Allotment of United States bonds 355 Conference of Governors in Minneapolis , 35$ Gold settlement fund 357 Discount rates 359 Informal rulings of the Federal Reserve Board 360 Law department - 363- Fiduciary powers granted , . -

The History of Counseling 1900S 1910S

The History of Counseling 1900s 1907 First Use of Systematized Guidance Jesse B. Davis, superintendent of the Grand Rapids school system, is first to implement a systematized guidance program in public schools. 1908 "Father of Guidance" Frank Parsons, the "Father of Guidance," founds Boston's Vocational Bureau, a major step in the institutionalization of vocational guidance. Parsons worked with young people who were in the process of making career decisions. He theorized that choosing a vocation was a matter of relating three factors: knowledge of work, knowledge of self, and matching of the two. Mental Health Reforms Clifford Beers, former Yale student, was hospitalized for mental illness several times during his life. He found conditions in mental institutions deplorable and exposed them in a book, A Mind That Found Itself. Beers advocated for better mental health facilities and reform in the treatment of the mentally ill. Beers was the impetus for the mental health movement in the United States, and his work was the forerunner of mental health counseling. 1910s 1913 First Counseling Association National Vocational Guidance Association founded, publishing literature and uniting professionals for the first time. 1917 Smith-Hughes Act This legislation provided funding for public schools to support vocational education. U.S. Army Employs Psychological Screening During World War I, the U.S. Army begins using numerous psychological instruments to screen soldiers, which are utilized in civilian populations after the war and become the basis for the popular movement called psychometrics. 1920s 1925 First Certification of Counselors The first certification of counselors took place in New York and Boston in the mid- 1920s.