University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC of the Manatee BERNARD

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER TROY1765 PIANO MUSIC OF Seven Preludes for Piano (1975) 15 The Manatee [2:36] 16 Stridin’ Thru The Olde Towne 1 Prelude [2:40] 2 Cello [2:47] During Prohibition In Search Of A Drink [2:42] 3 All Over The Piano [1:21] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 4 Ships Passing [4:12] (2014) BERNARD HOFFER 5 Prelude [1:24] Events & Excursions for Two Pianos 6 Calypso [3:52] 17 Big Bang Theory [3:15] 7 Franz Liszt Plays Ragtime [3:28] 18 Running [3:19] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 19 Wexford Noon [2:29] 20 Reverberations [3:12] Nine New Preludes for Piano (2016) 21 On The I-93 [2:23] Randall Hodgkinson & Leslie Amper, pianos 8 Undulating Phantoms [1:08] BERNARD HOFFER 9 A Walk In The Park [2:39] 10 Speed Chess [2:17] 22 Naked (2010) [5:05] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 11 Valse Sentimental [3:30] 12 Rabbits [1:06] Total Time = 60:03 13 Spirals [1:40] 14 Canon Inverso [1:44] PIANO MUSIC OF TROY1765 WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2019 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

Where to Study Jazz 2019

STUDENT MUSIC GUIDE Where To Study Jazz 2019 JAZZ MEETS CUTTING- EDGE TECHNOLOGY 5 SUPERB SCHOOLS IN SMALLER CITIES NEW ERA AT THE NEW SCHOOL IN NYC NYO JAZZ SPOTLIGHTS YOUNG TALENT Plus: Detailed Listings for 250 Schools! OCTOBER 2018 DOWNBEAT 71 There are numerous jazz ensembles, including a big band, at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. (Photo: Tony Firriolo) Cool perspective: The musicians in NYO Jazz enjoyed the view from onstage at Carnegie Hall. TODD ROSENBERG FIND YOUR FIT FEATURES f you want to pursue a career in jazz, this about programs you might want to check out. 74 THE NEW SCHOOL Iguide is the next step in your journey. Our As you begin researching jazz studies pro- The NYC institution continues to evolve annual Student Music Guide provides essen- grams, keep in mind that the goal is to find one 102 NYO JAZZ tial information on the world of jazz education. that fits your individual needs. Be sure to visit the Youthful ambassadors for jazz At the heart of the guide are detailed listings websites of schools that interest you. We’ve com- of jazz programs at 250 schools. Our listings are piled the most recent information we could gath- 120 FIVE GEMS organized by region, including an International er at press time, but some information might have Excellent jazz programs located in small or medium-size towns section. Throughout the listings, you’ll notice changed, so contact a school representative to get that some schools’ names have a colored banner. detailed, up-to-date information on admissions, 148 HIGH-TECH ED Those schools have placed advertisements in this enrollment, scholarships and campus life. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

-•-'" 8ft :: -'•• t' - ms>* '-. "*' - h.- ••• ; ''' ' : '..- - *'.-.•..'•••• lS*-sJ BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER see ERICH LEINSDORF, Director Contemporary JMusic Presented under the Auspices of the Fromm zMusic Foundation at TANGLEWOOD 1963 SEMINAR in Contemporary Music Seven sessions will be given on successive Friday afternoons (at 3:15) in the Chamber Music Hall. Four of these will precede the four Fromm Fellows' Concerts, and will consist of a re- hearsal and lecture by the Host of the following Monday Fromm Concert. July 12 AARON COPLAND July 19 GUNTHER SCHULLER July 26 I Twentieth Century Piano Music PAUL JACOBS August 2 YANNIS XENAKIS j August 9 Twentieth Century Choral Music ALFRED NASH PATTERSON & LORNA COOKE de VARON August 16 I LUKAS FOSS August 23 Round Table Discussion of Contemporary Music Yannis Xenakis, Gunther Schuller and lukas foss Composers 9 Forums There will be four Composers' Forums in the Chamber Music Hall: Wednesday, July 24 at 4:00 ] Thursday, August 1 at 8:00 Wednesday, August 7 at 4:00 Thursday, August 15 at 8:00 FROMM FELLOWS' CONCERTS Theatre-Concert Hall Four Monday Evenings at 8:00 'Programs JULY 15 AUGUST 5 AARON COPLAND, Host YANNIS XENAKIS, Host Varese Octandre (1924) Boulez ...Improvisations sur Mallarme, Copland Sextet (1937) No. 2 Chavez Soli (1933) Philippot ...Variations Schoenberg String Quartet No. 2, Op. 10 Mdcbe .. ..Canzone II (1908) Brown, E ...Pentathis Stravinsky Ragtime for Eleven Instruments Marie, E... Polygraphie-Polyphonique (1918) J. Ballif,C ...Double Trio, 35, Nos. 2 and 3 Milhaud... L'Enlevement d'Europe — Op. Xenakis Achorripsis Opera minute (1927) JULY 22 AUGUST 19 GUNTHER SCHULLER, Host LUKAS FOSS, Host Ives Chromatimelodtune Paz .Dedalus, 1950 Schoenberg Herzgewacb.se Goehr... -

MUNI 20101013 Piano 02 – Scott Joplin, King of Ragtime – Piano Rolls

MUNI 20101013 Piano 02 – Scott Joplin, King of Ragtime – piano rolls An der schönen, blauen Donau – Walzer, op. 314 (Johann Strauss, Jr., 1825-1899) Wiener Philharmoniker, Carlos Kleiber. Musikverein Wien, 1. 1. 1989 1 intro A 1:38 2 A 32 D 0:40 3 B 16 A 0:15 4 B 16 0:15 5 C 16 D 0:15 6 C 16 0:15 7 D 16 Bb 0:17 8 C 16 D 0:15 9 E 16 G 0:15 10 E 16 0:15 11 F 16 0:14 12 F 16 0:13 13 modul. 4 ►F 0:05 14 G 16 0:20 15 G 16 0:18 16 H 16 0:14 17 H 16 0:15 18 10+1 ►A 0:10 19 I 16 0:17 20 I 16 0:16 21 J 16 0:13 22 J 16 0:13 23 16+2 ►D 0:16 24 C 16 0:15 25 16 ►F 0:15 26 G 14 0:17 27 11 ►D 0:10 28 A 0:39 29 A1 16 0:16 30 A2 0:12 31 stretta 0:10 The Entertainer (Scott Joplin) (copyright John Stark & Son, Sedalia, 29. 12. 1902) piano roll Classics of Ragtime 0108 32 intro 4 C 0:06 33 A 16 0:23 34 A 16 0:23 35 B 16 0:23 36 B 16 0:23 37 A 16 0:23 38 C 16 F 0:22 39 C 16 0:22 40 modul. 4 ►C 0:05 41 D 16 0:22 42 D 16 0:23 43 The Crush Collision March (Scott Joplin, 1867/68-1917) 4:09 (J. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Bullets High Five

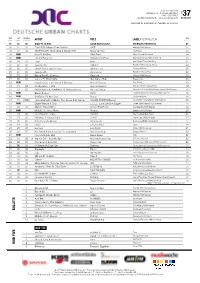

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 37 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 03.09.2020 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 08.09.2020 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 03 02 Drake Ft. Lil Durk Laugh Now Cry Later OVO/Republic/UMI/Universal 01 02 01 03 Cardi B Ft. Megan Thee Stallion WAP Atlantic/WMI/Warner 01 03 02 04 A$AP Ferg Ft. Nicki Minaj & MadeinTYO Move Ya Hips RCA/Sony 02 04 NEW Nas Ft. Hit-Boy Ultra Black Mass Appeal/Universal 04 05 NEW Capital Bra x Cro Frühstück In Paris Bra Musik/Urban/VEC/Universal 05 06 04 07 Tyga Ibiza Last Kings/Columbia/Sony 01 07 08 08 Apache 207 Bläulich TwoSides/Four Music/Sony 03 08 06 03 Jawsh 685 x Jason Derulo Savage Love Columbia/Sony 06 09 07 05 Apache 207 Unterwegs TwoSides/Four/Sony 03 10 16 02 Burna Boy Ft. Stormzy Real Life Atlantic/WMI/Warner 10 11 05 04 Juicy J Ft. Wiz Khalifa Gah Damn High Trippy/eOne 05 12 NEW Headie One Ft. AJ Tracey & Stormzy Ain't It Different Epic/Sony 12 13 18 09 Kynda Gray Ft. RIN Ayo Technology Division/Gold League/Sony 12 14 13 02 David Guetta & HUMAN(X) Ft. Various Artists Pa' La Cultura What A DJ/HUMAN(X)/Warner Latina/WMI/Warner 13 15 NEW Bausa & Juju 2012____ Downbeat/Warner Germany/WMD/Warner 15 16 NEW 24kGoldn Ft. Iann Dior Mood Columbia/Sony 16 17 10 10 Jack Harlow Ft. -

YOU CAN BE FUNNY Comedy Group Welcomes Newcomers

INSIDE Siouxland singer signs record deal weekender YOU CAN BE FUNNY Comedy group welcomes newcomers MANY EVENTS THIS WEEK SIOUX CITY’S FREE READ | JULY 23-29, 2020 | VOL. 21 ISSUE 34 | AT WWW.SIOUXLAND.NET: EVENTS,www.siouxland.netwww.siouxland.net MOVIE LISTINGS, . 07.23.2020 |BANDS 06.07.12 & | . MOREWeekenderWeekender |. 1 Submit an event: Do you have QUESTION OF THE WEEK an event you’d like to submit to our calendar? Call 712-293-4313, e-mail [email protected] or enter online at www.siouxland.net. Include event date, time, event name, contact name and phone If you had a soundtrack for your life, number. Deadline: Noon the Friday prior to what would be your theme song? publication. (Early deadlines in effect the week before holidays). CALENDAR BARS / PUBS JULY 23 Board Game Night, Brightside JULY 24 Cafe, 525 Fourth St., Sioux Chad Pauling Earl Horlyk Patrick Rooney Nikki Ahlquist Trailer Park Boys Trivia, The City. For a $5 cover charge you Retail and Digital Staff Writer Account Executive Graphic Designer Marquee, 1225 Fourth St., can access our ever-growing Advertising Director [email protected] prooney@ [email protected] Sioux City. Trivia Night at the board game library. Pizza and cpauling Since I had major dental siouxcityjournal.com My theme song would Marquee. (712) 560-4288. 8-10 grilled paninis are served along @siouxcityjournal.com surgery performed last It would be my favorite either be “Too Much p.m. with snack foods like chips and Given the world now: Brett week, “I Wanna Be song, “It’s a Beautiful Blood” or “Handwritten” muffins. -

Footnoted and Annotated Script

Footnoted and Annotated Script By Annie Leonard One of the problems with trying to use less stuff is that sometimes we feel like we really need it. What if you live in a city like, say, Cleveland and you want a glass of water? Are you going to take your chances and get it from the city tap? Or should you reach for a bottle of water that comes from the pristine rainforests of… Fiji? Well, Fiji brand water thought the answer to this question was obvious. So they built a whole ad campaign around it. It turned out to be one of the dumbest moves in advertising history.1 See the city of Cleveland didn’t like being the butt of Fiji’s joke so they did some tests and guess what? These tests showed a glass of Fiji water is lower quality, it loses taste tests against Cleveland tap and costs thousands of times more. 2 This story is typical of what happens when you test bottled water against tap water. Is it cleaner? Sometimes, sometimes not: in many ways, bottled water is less regulated than tap.3 Is it tastier? In taste tests across the country, people consistently choose tap over bottled water.4 These bottled water companies say they’re just meeting consumer demand - But who would demand a less sustainable, less tasty, way more expensive product, especially one you can get almost free in your 1. Fiji’s ad ran in national magazines with the tagline, “The label says 3. Municipal water in the U.S. -

Bach 2000 Organ Celebration-Ii

■ si Bach 2000 Organ Celebration-ii "Tracing the Footsteps of Johann Sebastian Bach" with Visiting Organist Kimberly Marshall I Sunday, September 24, 2000 at 3:00 pm Convocation Building Hail University of Alberta mm-07 Cb Program Program Notes In the autumn of 1705, Johann Sebastian Bach requested four weeks' leave from his I Prelude in E-FIat Major, BWV 552 Johann Sebastian Bach church in Amstadt to travel to Lubeck and leam from the famous Dieterich (1685-1750) Buxtehude, organist of the Marienkirche. He left for Ltlbeck in November and did not return until Febmaiy, at which time he was rebuked by the Amstadt Consistory 0. Ach Herr, mich armen Sunder, BWV 742 Johann Sebastian Bach for his prolonged absence, and also for his improper playing, making "curious 3. Jesu meine Freude, BWV 1105 (from the Neumeister Collection) variationes in the chorale" so that the congregation was confused by it. Bach's organ playing had clearly changed as a result of his time in Lilbeck, and his early organ Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 722 Johann Sebastian Bach works testify to his study of music in the north German style, with virtuosic (from the Amstadt Congregational Chorales) figuration, important pedal solos, and the altemation of improvisatory and contrapuntal sections. In addition, he was also very influenced by Italian and French organists, such as Frescobaldi and Grigny. In today's program, we'll trace the Ciacona in E Minor, BuxWV 159 Dieterich Buxtehude different paths Bach travelled in developing his own highly personal approach to Canzonetta in G Major, BuxWV 171 (1637-1707) organ composition. -

JANUARY 2017 First United Methodist Church Dalton, Georgia Cover

THE DIAPASON JANUARY 2017 First United Methodist Church Dalton, Georgia Cover feature on pages 24–25 CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN ͞ŐůŽǁŝŶŐ͕ŵŝƌĂĐƵůŽƵƐůLJůŝĨĞͲĂĸƌŵŝŶŐ performances” www.concertartists.com / 860-560-7800 Mark Swed, The Los Angeles Times THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Eighth Year: No. 1, In this issue Whole No. 1286 The Diapason begins its 108th year with Timothy Robson’s JANUARY 2017 report on the Organ Historical Society’s annual convention, Established in 1909 held in Philadelphia June 26–July 2, 2016. We also continue Joyce Robinson ISSN 0012-2378 David Herman’s series of articles on service playing. John Col- 847/391-1044; [email protected] lins outlines the lives and works of composers of early music www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, whose anniversaries (birth or death) fall in 2017. the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music John Bishop and Larry Palmer both examine the year and editor-at-large; Stephen will now take the reins as editor of The the season. Gavin Black is on hiatus; his column will return Diapason. I will assist behind the scenes during this transition. CONTENTS next month. Our cover feature is Parkey OrganBuilders’ Opus We also say farewell to Cathy LePenske, who designed this 16 at First United Methodist Church, Dalton, Georgia. journal during the past year; she is moving on to new respon- FEATURES sibilities. We offer Cathy many thanks for her work in making Thoughts on Service Playing Part II: Transposition Transitions The Diapason a beautiful journal, and we wish her well. by David Herman 18 As we begin a new year, changes are in process for our staff OHS 2016: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania at The Diapason. -

National Festival Chamber Orchestra Saturday, June 6

NATIONAL FESTIVAL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA SATURDAY, JUNE 6, 2015 . 8PM ELSIE & MARVIN DEKELBOUM CONCERT HALL PROGRAM Baljinder Sekhon Sun Dmitri Shostakovich/ Chamber Symphony, Op. 83a Rudolf Barshai Allegro Andantino Allegretto – Allegretto - intermission - Frank Martin Concerto for Seven Wind Instruments, Timpani, Percussion and String Orchestra Allegro Adagietto: Misterioso ed elegante Allegro vivace Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35 in D Major, K. 385 (“Haffner”) Allegro con spirito Andante Minuetto – Trio Finale: Presto 9 Sun array of instruments; that is, each The idea of using orchestral strings BALJINDER SEKHON player has a keyboard instrument (a to perform string quartets is hardly a marimba, a xylophone, a vibraphone), novelty. Gustav Mahler created string Born August 1, 1980, Fairfax, Virginia ‘skin’ (containing a drumhead), orchestra versions of Beethoven’s F Now living in Tampa, Florida wood and metal. In addition, the Minor Quartet (Op. 95) and Schubert’s three performers share a single large D Minor. Dimitri Mitropoulos gave This work for percussion trio was cymbal that is central to the staging. us a similar treatment of Beethoven’s composed in 2010–2011 under a At times the three percussion parts C-sharp Minor, Op. 131. Wilhelm commission from the Volta Trio, which are treated as one large instrument Furtwängler and Arturo Toscanini introduced it in a concert at Georgetown with three performers working toward performed and recorded individual University in Washington DC on a single musical character. Thus the movements from other Beethoven November 4, 2011. The score calls for orchestration and interaction alternate quartets. Toscanini also gave us a string- marimba, xylophone, vibraphone, large with each performer executing his/ orchestra version of Mendelssohn’s cymbal and “indeterminate skins, metals her own layers of sound to create a string octet — and Mendelssohn and woods.” Duration, 12 minutes. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat.