MTPII Shostakovich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

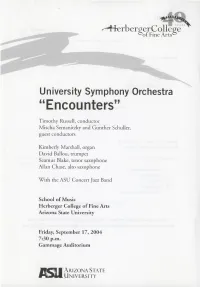

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

National Festival Chamber Orchestra Saturday, June 6

NATIONAL FESTIVAL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA SATURDAY, JUNE 6, 2015 . 8PM ELSIE & MARVIN DEKELBOUM CONCERT HALL PROGRAM Baljinder Sekhon Sun Dmitri Shostakovich/ Chamber Symphony, Op. 83a Rudolf Barshai Allegro Andantino Allegretto – Allegretto - intermission - Frank Martin Concerto for Seven Wind Instruments, Timpani, Percussion and String Orchestra Allegro Adagietto: Misterioso ed elegante Allegro vivace Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35 in D Major, K. 385 (“Haffner”) Allegro con spirito Andante Minuetto – Trio Finale: Presto 9 Sun array of instruments; that is, each The idea of using orchestral strings BALJINDER SEKHON player has a keyboard instrument (a to perform string quartets is hardly a marimba, a xylophone, a vibraphone), novelty. Gustav Mahler created string Born August 1, 1980, Fairfax, Virginia ‘skin’ (containing a drumhead), orchestra versions of Beethoven’s F Now living in Tampa, Florida wood and metal. In addition, the Minor Quartet (Op. 95) and Schubert’s three performers share a single large D Minor. Dimitri Mitropoulos gave This work for percussion trio was cymbal that is central to the staging. us a similar treatment of Beethoven’s composed in 2010–2011 under a At times the three percussion parts C-sharp Minor, Op. 131. Wilhelm commission from the Volta Trio, which are treated as one large instrument Furtwängler and Arturo Toscanini introduced it in a concert at Georgetown with three performers working toward performed and recorded individual University in Washington DC on a single musical character. Thus the movements from other Beethoven November 4, 2011. The score calls for orchestration and interaction alternate quartets. Toscanini also gave us a string- marimba, xylophone, vibraphone, large with each performer executing his/ orchestra version of Mendelssohn’s cymbal and “indeterminate skins, metals her own layers of sound to create a string octet — and Mendelssohn and woods.” Duration, 12 minutes. -

Dimitri Shostakovich: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

DIMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1919: Scherzo in F sharp minor for orchestra, op.1: 5 minutes 1921-22: Theme with Variations in B major for orchestra, op.3: 15 minutes 1922: “Two Fables of Krilov” for mezzo-soprano, female chorus and chamber Orchestra, op.4: 7 minutes 1923-24: Scherzo in E flat for orchestra, op.7: 4 minutes 1924-25: Symphony No.1 in F minor, op.10: 32 minutes Prelude and Scherzo for string orchestra, op.11: 10 minutes 1927: Symphony No.2 “October” for chorus and orchestra, op.14: 21 minutes 1927-28: Suite from the Opera “The Nose” for orchestra, op. 15A 1928: “Tahiti-Trot” for orchestra, op. 16: 4 minutes 1928-29/76: Suite from “New Babylon” for orchestra, op. 18B: 40 minutes 1928-32: Six Romances on Words by Japanese poets for tenor and orchestra, op.21: 13 minutes 1929: Suite from “The Bedbug” for orchestra, op.19B Symphony No.3 in E flat major “The First of May” for chorus and orchestra, op.20: 32 minutes 1929-30: Ballet “The Age of Gold”, op.22: 134 minutes (and Ballet Suite, op. 22A: 23 minutes) 1930-31: Suite from “Alone” for orchestra, op. 26 B Ballet “The Bolt”, op.27: 145 minutes (and Ballet Suite, op.27A: 29 minutes) 1930-32: Suite from the Opera “Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District” for orchestra, op. 29A: 6 minutes 1931: Suite from “Golden Mountains” for orchestra, op.30A: 24 minutes Overture “The Green Company”, op. 30C (lost) 1931-32: Suite from “Hamlet” for small orchestra, op. -

7 Pm, Thursday, 3 June 2010 Jackson Hall, Mondavi Center

7 pm, Thursday, 3 June 2010 Jackson Hall, Mondavi center UC Davis symphony orChestra Christian BalDini, mUsiC DireCtor anD Conductor Family ConCert 7 pm, thUrsDay, 3 JUne 2010 JaCkson hall, monDavi Center PROGRAM Oblivion Astor Piazzolla (1921–92) Kikimora Anatoly Liadov (1855–1914) Lament Ching-Yi Wang Winner, 2010 Composition Readings Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat Major Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Presto (1756–91) Shawyon Malek-Salehi, violin Andy Tan, viola Winners, 2010 Concerto Competition Symphony No. 10 in E Minor Dmitri Shostakovich Finale: Andante – Allegro (1906–75) D. Kern Holoman, conductor Distinguished Professor of Music and Conductor Emeritus This concert is being professionally recorded for the university archive. Please keep distractions to a minimum. Cell phones, and other similar electronic devices should be turned off completely. UC DAVIS SYMPHONY orCHESTRA Christian BalDini, mUsiC DireCtor anD Conductor amanDa WU, manaGer lisa eleazarian, liBrarian Names appear in seating order. violin i viola Flute horn Cynthia Bates, Andy Tan, Susan Monticello, Rachel Howerton, concertmaster * principal * principal * principal * Yosef Farnsworth, Meredith Powell, Abby Green, Stephen Hudson concertmaster * principal * assistant principal * Adam Morales, Shawyon Malek-Salehi, Caitlin Murray Michelle Hwang principal assistant concertmaster * Melissa Lyans Chris Brown Bobby Olsen, Lucile Cain Ali Spurgeon co-principal Sharon Tsao * Pablo Frias oboe Maya Abramson* Andrew Benson Jaclyn Howerton, trumpet Raphael Moore * principal * Andrew -

Yevgeny Dolmatovsky

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Yevgeny Dolmatovsky Rabbi Hillel taught: Do not judge your fellow until you have stood in his place. Pirkei Avot 2:5. Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s … Matthew 22:21 by Sam Silverman evgeny Dolmatovsky wrote many of the texts which were set to music by Shostakovich. Most of these were either patriotic songs, or songs reflecting and eulogising the Communist Party propaganda positions. Because of these Ylatter poems he has been described and known as a second or third rate poet, and as a loyal party hack. The truth, however, is more complex, and one must look deeper into his history to understand him. Transliteration of names from the Cyrillic Russian alphabet can lead to variations. In this paper I have used “Dolmatovsky” and “Dolmatovskii” interchangeably for the Russian “Долматовский”. In one case, that of the doctoral thesis, in Ger- man, of Yevgeny’s father, the transliteration into German becomes “Dolmatowsky.” Early Years Yevgeny Aronovich Dolmatovsky was born in Moscow on May 5, 1915 (Obituary, The Independent (London), Novem- ber 17, 1994, hereinafter “Obituary”), the son of a famous Moscow lawyer who was later executed as an “enemy of the people” (Vaksberg, p. 262). Dolmatovsky died in Moscow on September 10, 1994 (Obituary, loc. cit.). His poems were very popular, and the royalties from the poems and from films had provided him with millions of roubles (Obituary, loc. cit.). His parents were Aron Moiseevich and Adel Dolmatovsky (International Who’s Who, see, e.g., volumes for 1989–1992). His father was born in Rostov-on-Don on 13 November 1880, the son of a merchant, Moisei [Moses] and his wife, Theo- dosia. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 72

^ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY s^^ HENRY LEE HI SEVENTY-SECOND SEASON 195 2-T953 Sanders Theatre, Cambridge \^^arvard University^ Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-second Season, 1952-1953) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin, Joseph de Pasquale Raymond Allard Concert-master Jean Cauhap^ Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Georges Fourel Theodore Brewster George Zazofsky Eugen Lehner Rolland Tapley Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Norbert Lauga George Humphrey Richard Plaster Harry Dubbs Jerome lipson Vladimir ResnikofF Louis Ar litres Horns Harry Dickson Robert Karol James Stagliano Einar Hansen Reuben Green Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici Bernard Kadinoff Harold Meek Gottfried Wilfinger Vincent Mauricci Paul Keaney Emil Kornsand Walter Macdonald Roger Schermanski Violoncellos Osbourne McConathy Carlos Pinfield Samuel Mayes Paul Fedorovsky Alfred Zighera Trumpets Minot Beale Jacobus Langendoen Roger Voisin Herman Silberman Mischa Nieland Marcel Lafosse Stanley Benson Hippolyte Droeghmans Armando Ghitalla Leo Panasevich Karl Zeise Gerard Goguen Sheldon Rotenberg Josef Zimbler Clarence Knudson Bernard Parronchi Trombones Pierre Mayer Leon Marjollet {acob Raichman Manuel Zung William Moyer Kauko Kahila Samuel Diamond Flutes [osef Orosz Victor Manusevitch Doriot Anthony James Nagy James Pappoutsakis Tuba Leon Gorodetzky Phillip Kaplan Vinal Smith Raphael Del Sordo Piccolo Melvin Bryant Harps Lloyd Stonestreet George Madsen Saverio Messina Oboes Bernard Zighera -

Evgeni Mravinsky Discography

FRANK FORMAN AND KENZO AMOH Evgeni Mravinsky Discography Evgeni Alexandrovich Mravinsky (1903 I 6 I 4 St. Petersburg -1988I1I19 Leningrad) General Notes 1. All records are stereo unless noted as Grammophon's original Tchaikovsky monaural. Symphonies. See the List of Record Labels 2. LPs are 30 centimeters (12 inches) in diam below. eter unless stated otherwise. 9. This discography is a revision ofKenzo 3. The orchestra is the Leningrad Amoh, Frank Forman, and Hiroshi Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra unless Hashizume, Mravinsky Discography stated otherwise. (Osaka: The Japanese Mravinsky Society, 4. Recording data are mostly based on infor 1993 March 20). Agreat deal of peripheral mation from Alexandr Nevsorov (Moscow). material, such as photographs, a biography Discrepancies are noted. of the conductor, and several lists of con 5. ·~ before a recording date means that the certs, was omitted. exact date is unknown. The date given is 10. Grateful acknowledgements are owed to the earliest date that recording engineers several people: 1. Hiroshi Hashizume, sec were known to have checked the recording. retary of the Japanese Mravinsky Society; Alexandr Nevzorov (the discographers' cor 2. Alexandr Nevzorov, a Russian correspon respondent in Moscow) estimates that the dent, for his research in various archives; actual recording was made either on that 3. William D. Curtis, for the first known day or any time during the preceding compilation ofMravinsky's recordings; 4. month. Some anomalies, like the Donald R. Hodgman, a collector in New Ovsyaniko-Kulikovksy Symphony, remain. York City, for the loan of several dozen LPs; 6. Soviet LPs are numbered consecutively on 5. Paul Miller, a Los Angeles collector, for each side of the disc, instead of one number making a great many patient A-B compar for the entire disc. -

Of New Collected Works

DSCH PUBLISHERS CATALOGUE of New Collected Works FOR HIRE For information on purchasing our publications and hiring material, please apply to DSCH Publishers, 8, bld. 5, Olsufievsky pereulok, Moscow, 119021, Russia. Phone: 7 (499) 255-3265, 7 (499) 766-4199 E-mail: [email protected] www.shostakovich.ru © DSCH Publishers, Moscow, 2019 CONTENTS CATALOGUE OF PUBLICATIONS . 5 New Collected Works of Dmitri Shostakovich .................6 Series I. Symphonies ...............................6 Series II. Orchestral Compositions .....................8 Series III. Instrumental Concertos .....................10 Series IV. Compositions for the Stage ..................11 Series V. Suites from Operas and Ballets ...............12 Series VI. Compositions for Choir and Orchestra (with or without soloists) ....................13 Series VII. Choral Compositions .......................14 Series VIII. Compositions for Solo Voice(s) and Orchestra ...15 Series IX. Chamber Compositions for Voice and Songs ....15 Series X. Chamber Instrumental Ensembles ............17 Series XI. Instrumental Sonatas . 18 Series ХII. Piano Compositions ........................18 Series ХIII. Incidental Music ...........................19 Series XIV. Film Music ...............................20 Series XV. Orchestrations of Works by Other Composers ...22 Publications ............................................24 Dmitri Shostakovich’s Archive Series .....................27 Books ..............................................27 FOR HIRE ..............................................30 -

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich Dmiti Shostakovich photo © Booseyprints __An Introduction to the music of Dmitri Shostakovich__ _by Gerard McBurney_ Dmitri Shostakovich is regarded by musicians and audiences alike as one of the most important and powerful composers of the 20th century. His music reflects his own personal journey through some of the most turbulent and tragic times of modern history. Even in his own lifetime many of his works established themselves internationally as part of the standard repertoire, and since his death his fame has increased year by year. Nowadays most of his 15 symphonies, the entire cycle of 15 string quartets, his _24 Preludes and Fugues_ for piano and his opera _Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk_, have come to occupy a central place in the experience of music lovers. And yet Shostakovich, a hugely prolific composer, wrote vast amounts of other music that is still hardly known. And much of it reflects sides to his character - humorous, sarcastic, absurd, funny, theatrical, deliciously tuneful - quite different from the dark and tragic mood most people associate with his name. In particular, when he was young, Shostakovich produced a stream of music for the theatre and cinema: operas, operettas, ballets, music-hall shows, incidental music for all kinds of plays from Shakespeare to propoganda, live music for silent cinema, recorded scores for early sound-movies, even an enchanting children's cartoon-opera. Much of this is music in a lighter or more popular vein, sparkling like champagne and a treat for musicians and audiences. It richly deserves to be heard and fascinatingly deepens our sense of the achievement of this remarkable artist. -

Proquest Dissertations

M u Ottawa L'Unh-wsiie eanadienne Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES IfisSJ FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L'Universite canadienne Canada's university Jada Watson AUTEUR DE LA THESE /AUTHOR OF THESIS M.A. (Musicology) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Music lATJULfEJ^LTbliP^ Aspects of the "Jewish" Folk Idiom in Dmitri Shostakovich's String Quartet No. 4, OP.83 (1949) TITREDE LA THESE/TITLE OF THESIS Phillip Murray Dineen _________________^ Douglas Clayton _______________ __^ EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE / THESIS EXAMINERS Lori Burns Roxane Prevost Gary W, Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies ASPECTS OF THE "JEWISH" FOLK IDIOM IN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH'S STRING QUARTET NO. 4, OP. 83 (1949) BY JADA WATSON Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master's of Arts degree in Musicology Department of Music Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Jada Watson, Ottawa, Canada, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48520-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48520-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant -

JOANN FALLETTA, Conductor ELIZABETH CABALLERO, Soprano

LoKo Arts Festival Concert 2017 Festival Helen M. Hosmer Hall Performed April 29, 2017 Gloria (1959) Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) I. Gloria II. Laudamus te III. Domine Deus IV. Domine fili unigenite V. Domine Deus, Agnus Dei VI. Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris JOANN FALLETTA, Conductor ELIZABETH CABALLERO, Soprano CRANE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Ching-Chun Lai, Director CRANE CHORUS Jeffrey Francom, Director Texts & Translations Gloria Gloria in excelsis Deo. Et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis. Laudamus te, benedicimus te, adoramus te, glorificamus te; Gratias agimus, agimus tibi, Propter magnam gloriam tuam. Domine Deus, Rex coelestis! Deus, Pater omnipotens! Domine, Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe! Domine Deus! Agnus Dei! Filius Patris! Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis. Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram. Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis. Quoniam tu solus sanctus. Tu solus Dominus. Tu solus altissimus, Jesu Christe! Cum Sancto Spirtitu in gloria Dei patris. Amen. Program Notes by Dr. Gary Busch The ebullient optimism of Francis Poulenc’s Gloria inhabits a world as distant as can be imagined from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s fatalistic vision expressed in The Bells. Yet, despite their contrasting spiritual viewpoints, the two works on tonight’s program share the common feature of having been inspired by a symbol of profound significance deeply harbored within the heart of each composer. For Rachmaninoff, the impetus was the comforting recollection of particular ever- present sounds that reassure humanity amid the bleakness of impending mortality – for Poulenc, it was the joyous rekindling of Catholicism, the religion of his childhood. Further uniting both works is the superlative esteem in which their composers held them. -

Senior Recital: Jarod Dylan Boles, Double Bass

Kennesaw State University College of the Arts School of Music presents Senior Recital Jarod Dylan Boles, double bass Stephanie Ng, piano Tuesday, May 6, 2014 4:00 p.m. Music Building Recital Hall One Hundred Thirty-eighth Concert of the 2013-14 Concert Season Program ZOLTÁN KODÁLY (1882-1967) Epigrams 1. Lento 2. Andantino 3. 4. Moderato 5. Allegretto 6. 7. Con moto DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Adagio from Unforgettable 1919 MAX BRUCH (1838-1920) Kol Nidrei Intermission ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK (1841-1904) String Quintet No. 2 in G Major, Op. 77 I. Allegro con fuoco II. Scherzo. Allegro vivace III. Poco andante IV. Allegro assai Ryan Gregory, violin Jonathan Urizar, violin Justin Brookins, viola Dorian Silva, cello This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree Bachelor of Music in Performance. Mr. Boles studies doiuble bass with Joseph McFadden. Program Notes Epigrams ZOLTÁN KODÁLY (1882-1967) The nine Epigrams (Epigrammák) were composed in 1954 along with several oth- er educational works designed to exemplify Kodály’s method of musical education. They were originally conceived as vocalises, for a wordless voice and piano ac- companiment, but the voice part can be adapted to almost any instrument. In these little pieces, grave, gay or lyrical, with their discreet polyphonic imitations between melody and accompaniment, the Hungarian accent is so perfectly absorbed into Kodály’s habit of discourse that there is hardly a hint of the exotic about them: they simply testify to a rare serenity of spirit and delight in music-making. - notes by Calum MacDonald © 2010 http://www.hyperion-records.co.uk/dw.asp?dc=W12994_67829&vw=dc Adagio from Unforgettable 1919 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) After being virulently condemned as a "formalist," at the 1948 Composers' Union Congress, Shostakovich could not possibly continue composing large scale, ab- stract symphonic canvases.