Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JEWS and JAZZ (Lorry Black and Jeff Janeczko)

UNIT 8 JEWS, JAZZ, AND JEWISH JAZZ PART 1: JEWS AND JAZZ (Lorry Black and Jeff Janeczko) A PROGRAM OF THE LOWELL MILKEN FUND FOR AMERICAN JEWISH MUSIC AT THE UCLA HERB ALPERT SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIT 8: JEWS, JAZZ, AND JEWISH JAZZ, PART 1 1 Since the emergence of jazz in the late 19th century, Jews have helped shape the art form as musicians, bandleaders, songwriters, promoters, record label managers and more. Working alongside African Americans but often with fewer barriers to success, Jews helped jazz gain recognition as a uniquely American art form, symbolic of the melting pot’s potential and a pluralistic society. At the same time that Jews helped establish jazz as America’s art form, they also used it to shape the contours of American Jewish identity. Elements of jazz infiltrated some of America’s earliest secular Jewish music, formed the basis of numerous sacred works, and continue to influence the soundtrack of American Jewish life. As such, jazz has been an important site in which Jews have helped define what it means to be American, as well as Jewish. Enduring Understandings • Jazz has been an important platform through which Jews have helped shape the pluralistic nature of American society, as well as one that has shaped understandings of American Jewish identity. • Jews have played many different roles in the development of jazz, from composers to club owners. • Though Jews have been involved in jazz through virtually all phases of its development, they have only used it to express Jewishness in a relatively small number of circumstances. -

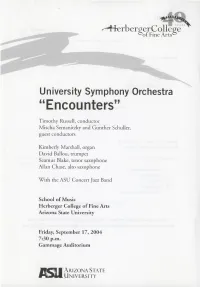

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 (1923-5) Yuri Ahronovich/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Overture on Russian and Kirghiz Folk Themes) MELODIYA SM 02581-2/MELODIYA ANGEL SR-40192 (1972) (LP) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 5) SUPRAPHON ANCERL EDITION SU 36992 (2005) (original LP release: SUPRAPHON SUAST 50576) (1964) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, Festive Overture, October, The Song of the Forest, 5 Fragments, Funeral-Triumphal Prelude, Novorossiisk Chimes: Excerpts and Chamber Symphony, Op. 110a) DECCA 4758748-2 (12 CDs) (2007) (original CD release: DECCA 425609-2) (1990) Rudolf Barshai/Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1994) ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 6324 (11 CDs) (2003) Rudolf Barshai/Vancouver Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. -

THE RUSSIAN CIVIL WAR Also by A

THE RUSSIAN CIVIL WAR Also by A. B. Murphy ASPECTIVAL USAGE IN RUSSIAN INlRODUCTION AND COMMENTARY TO SHOLOKHOV'S TlKHlY DON MIKHAIL ZOSHCHENKO: A Literary Project Also by G. R. Swain EASTERN EUROPE SINCE 1945 (co-author) THE ORIGINS OF THE RUSSIAN CIVIL WAR RUSSIAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY AND THE LEGAL LABOUR MOVEMENT,1906-14 The Russian Civil War Documents from the Soviet Archives Edited by v. P. Butt Senior Scientific Collaborator Institute of Russian History Russian Academy of Sciences A. B. Murphy Professor Emeritus of Russian University of Ulster N. A. Myshov Senior Scientific Collaborator and ChiefArchivist Russian State Military Archive and G. R. Swain Professor ofHistory University of the West of England First published in Great Britain 1996 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-333-59319-6 ISBN 978-1-349-25026-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-25026-4 First published in the United States of America 1996 by ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 ISBN 978-0-312-16337-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Russian civil war: documents from the Soviet archives / edited by V. P. Butt ... ret al.l p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-312-16337-2 (cloth) I. Soviet Union-History-Revolution, 1917-1921-Sources. I. Butt, V. P. DK265.A5372 1996 947.084'I-dc20 96-19904 CIP Selection, editorial matter and translation © V. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 31 No. 1, Spring 2015

New Horizons Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements, Part II The Viola Concertos of J. G. Graun and M. H. Graul Unconfused The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet Volume 31 Number 1 Number 31 Volume Turn-Out in Standing Journal of the American Viola Society Viola American the of Journal Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2015: Volume 31, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 9 Primrose Memorial Concert 2015 Myrna Layton reports on Atar Arad’s appearance at Brigham Young University as guest artist for the 33rd concert in memory of William Primrose. p. 13 42nd International Viola Congress in Review: Performing for the Future of Music Martha Evans and Lydia Handy share with us their experiences in Portugal, with a congress that focused on new horizons in viola music. Feature Articles p. 19 Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II After a fascinating look at Borisovsky’s life in the previous issue, Elena Artamonova delves into the violist’s arrangements and editions, with a particular focus on the Glinka’s viola sonata p. 31 The Viola Concertos of J.G. Graun and M.H. Graul Unconfused The late Marshall ineF examined the viola concertos of J. G. Graul, court cellist for Frederick the Great, in arguing that there may have been misattribution to M. H. Graul. Departments p. 39 With Viola in Hand: A Passion Absolute–The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet The Absolute eroZ Quartet has captured the attention of violists in some 60 countries. -

A Russian Eschatology: Theological Reflections on the Music of Dmitri Shostakovich

A Russian Eschatology: Theological Reflections on the Music of Dmitri Shostakovich Submitted by Anna Megan Davis to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology in December 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. 2 3 Abstract Theological reflection on music commonly adopts a metaphysical approach, according to which the proportions of musical harmony are interpreted as ontologies of divine order, mirrored in the created world. Attempts to engage theologically with music’s expressivity have been largely rejected on the grounds of a distrust of sensuality, accusations that they endorse a ‘religion of aestheticism’ and concern that they prioritise human emotion at the expense of the divine. This thesis, however, argues that understanding music as expressive is both essential to a proper appreciation of the art form and of value to the theological task, and aims to defend and substantiate this claim in relation to the music of twentieth-century Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich. Analysing a selection of his works with reference to culture, iconography, interiority and comedy, it seeks both to address the theological criticisms of musical expressivism and to carve out a positive theological engagement with the subject, arguing that the distinctive contribution of Shostakovich’s music to theological endeavour lies in relation to a theology of hope, articulated through the possibilities of the creative act. -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry. -

Link Shostakovich.Txt

FRAMMENTI DELL'OPERA "TESTIMONIANZA" DI VOLKOV: http://www.francescomariacolombo.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i d=54&Itemid=65&lang=it LA BIOGRAFIA DEL MUSICISTA DA "SOSTAKOVIC" DI FRANCO PULCINI: http://books.google.it/books?id=2vim5XnmcDUC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=testimonianza+v olkov&source=bl&ots=iq2gzJOa7_&sig=3Y_drOErxYxehd6cjNO7R6ThVFM&hl=it&sa=X&ei=yUi SUbVkzMQ9t9mA2A0&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=testimonianza%20volkov&f=false LA PASSIONE PER IL CALCIO http://www.storiedicalcio.altervista.org/calcio_sostakovic.html CENNI SULLA BIOGRAFIA: http://www.52composers.com/shostakovich.html PERSONALITA' DEL MUSICISTA NELL'APPOSITO PARAGRAFO "PERSONALITY" : http://www.classiccat.net/shostakovich_d/biography.php SCHEMA MOLTO SINTETICO DELLA BIOGRAFIA: http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/dmitry-shostakovich-344.php La mia droga si chiama Caterina La mia droga si chiama Caterina “Io mi aggiro tra gli uomini come fossero frammenti di uomini” (Nietzsche) In un articolo del 1932 sulla rivista “Sovetskoe iskusstvo”, Sostakovic dichiarava il proprio amore per Katerina Lvovna Izmajlova, la protagonista dell’opera che egli stava scrivendo da oltre venti mesi, e che vedrà la luce al Teatro Malyi di Leningrado il 22 gennaio 1934. Katerina è una ragazza russa della stessa età del compositore, ventiquattro, venticinque anni (la maturazione artistica di Sostakovic fu, com’è noto, precocissima), “dotata, intelligente e superiore alla media, la quale rovina la propria vita a causa dell’opprimente posizione cui la Russia prerivoluzionaria la assoggetta”. E’ un’omicida, anzi un vero e proprio serial killer al femminile; e tuttavia Sostakovic denuncia quanta simpatia provi per lei. Nelle originarie intenzioni dell’autore, “Una Lady Macbeth del distretto di Mcensk” avrebbe inaugurato una trilogia dedicata alla donna russa, còlta nella sua essenza immutabile attraverso differenti epoche storiche. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

Download Booklet

95782 The cello concerto genre has a relatively short history. Before the 19th century, the only composers a few other works, including Monn’s fine, characterful Cello Concerto in G minor. Monn died of of stature who wrote such works were Vivaldi, C.P.E. Bach, Haydn and Boccherini. Considering the tuberculosis at the age of 33. problem inherent in the cello’s lower register, the potential difficulty of projecting its tone against Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) made phenomenal contributions to the history of the symphony, the weight of an orchestra, it is rather ironic that most of the great concertos for the instrument the string quartet, the piano sonata and the piano trio. He generally found concerto form less were composed later than the Baroque or Classical periods. The orchestra of these earlier periods stimulating to his creative imagination, but he did compose several fine examples. In 1961 the was smaller and lighter – a more accommodating accompaniment for the cello – whereas during unearthing of a set of parts for Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C major in Radenín Castle (now in the 19th century the symphony orchestra was significantly expanded, so that composers had to the Czech Republic) proved to be one of the most exciting discoveries in 20th-century musicology. take more care to avoid overwhelming the soloist. Probably dating from the early 1760s, the concerto is believed to have been composed for Joseph Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) composed several hundred concertos while employed as a violin Weigl, principal cellist of Haydn’s orchestra. This is the more rhythmically arresting of Haydn’s teacher (and, from 1716, as ‘maestro dei concerti’) at the Venetian girls’ orphanage known as authentic cello concertos. -

“Music Is Music”: Anton Ivanovich Is Upset (1941) and Soviet Musical Politics

“Music is Music”: Anton Ivanovich is Upset (1941) and Soviet Musical Politics PETER KUPFER Abstract In this article I analyze the musical politics of the 1941 Soviet film Anton Ivanovich serditsya (Anton Ivanovich Is Upset), directed by Aleksandr Ivanovsky, original score by Dmitry Kabalevsky. The film tells the story of the musical “enlightenment” of the eponymous Anton Ivanovich Voronov, an old, stodgy organ professor who is interested only in the “serious” music of J.S. Bach. His daughter, Sima, however, wishes to become an operetta singer and falls in love with a composer of “light” music, Aleksey Mukhin, which upsets the professor greatly. Thanks to a miraculous intervention by Bach himself, Anton Ivanovich ultimately sees his error and accepts Muhkin, going so far as to perform the organ part in Mukhin’s new symphonic poem. While largely a lighthearted and fun tale, the caricature and censure of another young, but veiled “formalist” composer, Kerosinov, reflects the darker side of contemporary Soviet musical aesthetics. In the way that it does and does not work out the uneasy relationship between serious, light, and formalist music, I argue that Anton Ivanovich serditsya realistically reflects the paradoxical nature of Soviet musical politics in the late 1930s. Alexander Ivanovsky’s 1941 film Anton Ivanovich serditsya (Anton Ivanovich is Upset, hereafter AIS) tells the story of Anton Ivanovich Voronov (from voron, “raven”), a venerated professor at the conservatory who idolizes the music of “serious” composers, particularly J.S. Bach.1 His earnestness is established from the very start: we first see him in deep contemplation and reverence performing Bach’s somber Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582, which accompanies the film’s opening credits. -

Jewish Giants of Music

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Fall 2004/Winter 2005 Jewish Giants of Music Also: George Washington and the Jews Yiddish “Haven to Home” at the Theatre Library of Congress Posters Milken Archive of American Jewish Music th Anniversary of Jewish 350 Settlement in America AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Fall 2004/Winter 2005 ~ OFFICERS ~ CONTENTS SIDNEY LAPIDUS President KENNETH J. BIALKIN 3 Message from Sidney Lapidus, 18 Allan Sherman Chairman President AJHS IRA A. LIPMAN LESLIE POLLACK JUSTIN L. WYNER Vice Presidents 8 From the Archives SHELDON S. COHEN Secretary and Counsel LOUISE P. ROSENFELD 12 Assistant Treasurer The History of PROF. DEBORAH DASH MOORE American Jewish Music Chair, Academic Council MARSHA LOTSTEIN Chair, Council of Jewish 19 The First American Historical Organizations Glamour Girl GEORGE BLUMENTHAL LESLIE POLLACK Co-Chairs, Sports Archive DAVID P. SOLOMON, Treasurer and Acting Executive Director BERNARD WAX Director Emeritus MICHAEL FELDBERG, PH.D. Director of Research LYN SLOME Director of Library and Archives CATHY KRUGMAN Director of Development 20 HERBERT KLEIN Library of Congress Director of Marketing 22 Thanksgiving and the Jews ~ BOARD OF TRUSTEES ~ of Pennsylvania, 1868 M. BERNARD AIDINOFF KENNETH J. BIALKIN GEORGE BLUMENTHAL SHELDON S. COHEN RONALD CURHAN ALAN M. EDELSTEIN 23 George Washington RUTH FEIN writes to the Savannah DAVID M. GORDIS DAVID S. GOTTESMAN 15 Leonard Bernstein’s Community – 1789 ROBERT D. GRIES DAVID HERSHBERG Musical Embrace MICHAEL JESSELSON DANIEL KAPLAN HARVEY M. KRUEGER SAMUEL KARETSKY 25 Jews and Baseball SIDNEY LAPIDUS PHILIP LAX in the Limelight IRA A. LIPMAN NORMAN LISS MARSHA LOTSTEIN KENNETH D. MALAMED DEBORAH DASH MOORE EDGAR J.