HISTORICAL and ANALYTICAL OVERVIEWS on DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH's TWENTY-FOUR PRELUDES and FUGUES by Jihong Park a Thesis Submitte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

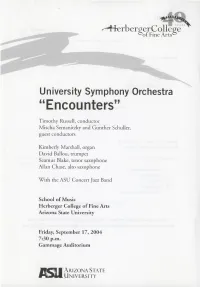

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Building Cultural Bridges: Benjamin Britten and Russia

BUILDING CULTURAL BRIDGES: BENJAMIN BRITTEN AND RUSSIA Book Review of Benjamin Britten and Russia, by Cameron Pyke Maja Brlečić Benjamin Britten visited Soviet Russia during a time of great trial for Soviet artists and intellectuals. Between the years of 1963 and 1971, he made six trips, four formal and two private. During this time, the communist regime within the Soviet Union was at its heyday, and bureaucratization of culture served as a propaganda tool to gain totalitarian control over all spheres of public activity. This was also a period during which the international political situation was turbulent; the Cold War was at its height with ongoing issues of nuclear armaments, the tensions among the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom ebbed and flowed, and the atmosphere of unrest was heightened by the Vietnam War. It was not until the early 1990s that the Iron Curtain collapsed, and the Cold War finally ended. While the 1960s were economically and culturally prosperous for Western Europe, those same years were tough for communist Eastern Europe, where the people still suffered from the aftermath of Stalin thwarting any attempts of artistic openness and creativity. As a result, certain efforts were made to build cultural bridges between West and East, including efforts that were significantly aided by Britten’s engagements. In his book Benjamin Britten and Russia, Cameron Pyke portrays the bridging of the vast gulf achieved through Britten’s interactions with the Soviet Union, drawing skillfully from historical and cultural contextualization, Britten’s and Pears’s personal accounts, interviews, musical scores, a series of articles about Britten published in the Soviet Union, and discussions of cultural and political figures of the time.1 In the seven chapters of his book, Pyke brings to light the nature of Britten’s six visits and offers detailed accounts of Britten’s affection for Russian music and culture. -

Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba

COMPARISON AND CONTRAST OF PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF THE TUBA IN IGOR STRAVINSKY’S THE RITE OF SPRING, DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN D MAJOR, OP. 47, AND SERGEI PROKOFIEV’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN B FLAT MAJOR, OP. 100 Roy L. Couch, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2006 APPROVED: Donald C. Little, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Keith Johnson, Committee Member Brian Bowman, Coordinator of Brass Instrument Studies Graham Phipps, Program Coordinator of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Couch, Roy L., Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba in Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 47, and Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, Op. 100, Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2006, 46 pp.,references, 63 titles. Performance practice is a term familiar to serious musicians. For the performer, this means assimilating and applying all the education and training that has been pursued in a course of study. Performance practice entails many aspects such as development of the craft of performing on the instrument, comprehensive knowledge of pertinent literature, score study and listening to recordings, study of instruments of the period, notation and articulation practices of the time, and issues of tempo and dynamics. The orchestral literature of Eastern Europe, especially Germany and Russia, from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century provides some of the most significant and musically challenging parts for the tuba. -

A Russian Eschatology: Theological Reflections on the Music of Dmitri Shostakovich

A Russian Eschatology: Theological Reflections on the Music of Dmitri Shostakovich Submitted by Anna Megan Davis to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology in December 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. 2 3 Abstract Theological reflection on music commonly adopts a metaphysical approach, according to which the proportions of musical harmony are interpreted as ontologies of divine order, mirrored in the created world. Attempts to engage theologically with music’s expressivity have been largely rejected on the grounds of a distrust of sensuality, accusations that they endorse a ‘religion of aestheticism’ and concern that they prioritise human emotion at the expense of the divine. This thesis, however, argues that understanding music as expressive is both essential to a proper appreciation of the art form and of value to the theological task, and aims to defend and substantiate this claim in relation to the music of twentieth-century Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich. Analysing a selection of his works with reference to culture, iconography, interiority and comedy, it seeks both to address the theological criticisms of musical expressivism and to carve out a positive theological engagement with the subject, arguing that the distinctive contribution of Shostakovich’s music to theological endeavour lies in relation to a theology of hope, articulated through the possibilities of the creative act. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Seattle Symphony October 2017 Encore

OCTOBER 2017 LUDOVIC MORLOT, MUSIC DIRECTOR BEATRICE RANA PLAYS PROKOFIEV GIDON KREMER SCHUMANN VIOLIN CONCERTO LOOKING AHEAD: MORLOT C O N D U C T S BERLIOZ CONTENTS My wealth. My priorities. My partner. You’ve spent your life accumulating wealth. And, no doubt, that wealth now takes many forms, sits in many places, and is managed by many advisors. Unfortunately, that kind of fragmentation creates gaps that can hold your wealth back from its full potential. The Private Bank can help. The Private Bank uses a proprietary approach called the LIFE Wealth Cycle SM to ind those gaps—and help you achieve what is important to you. To learn more, please visit unionbank.com/theprivatebank or contact: Lisa Roberts Managing Director, Private Wealth Management [email protected] 4157057159 Wills, trusts, foundations, and wealth planning strategies have legal, tax, accounting, and other implications. Clients should consult a legal or tax advisor. ©2017 MUFG Union Bank, N.A. All rights reserved. Member FDIC. Union Bank is a registered trademark and brand name of MUFG Union Bank, N.A. EAP full-page template.indd 1 7/17/17 3:08 PM CONTENTS OCTOBER 2017 4 / CALENDAR 6 / THE SYMPHONY 10 / NEWS FEATURES 12 / BERLIOZ’S BARGAIN 14 / MUSIC & IMAGINATION CONCERTS 15 / October 5 & 7 ENIGMA VARIATIONS 19 / October 6 ELGAR UNTUXED 21 / October 12 & 14 GIDON KREMER SCHUMANN VIOLIN CONCERTO 24 / October 13 [UNTITLED] 1 26 / October 17 NOSFERATU: A SYMPHONY OF HORROR 27 / October 20, 21 & 27 VIVALDI FOUR SEASONS 30 / October 26 & 29 21 / GIDON KREMER SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY NO. -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry. -

Link Shostakovich.Txt

FRAMMENTI DELL'OPERA "TESTIMONIANZA" DI VOLKOV: http://www.francescomariacolombo.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i d=54&Itemid=65&lang=it LA BIOGRAFIA DEL MUSICISTA DA "SOSTAKOVIC" DI FRANCO PULCINI: http://books.google.it/books?id=2vim5XnmcDUC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=testimonianza+v olkov&source=bl&ots=iq2gzJOa7_&sig=3Y_drOErxYxehd6cjNO7R6ThVFM&hl=it&sa=X&ei=yUi SUbVkzMQ9t9mA2A0&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=testimonianza%20volkov&f=false LA PASSIONE PER IL CALCIO http://www.storiedicalcio.altervista.org/calcio_sostakovic.html CENNI SULLA BIOGRAFIA: http://www.52composers.com/shostakovich.html PERSONALITA' DEL MUSICISTA NELL'APPOSITO PARAGRAFO "PERSONALITY" : http://www.classiccat.net/shostakovich_d/biography.php SCHEMA MOLTO SINTETICO DELLA BIOGRAFIA: http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/dmitry-shostakovich-344.php La mia droga si chiama Caterina La mia droga si chiama Caterina “Io mi aggiro tra gli uomini come fossero frammenti di uomini” (Nietzsche) In un articolo del 1932 sulla rivista “Sovetskoe iskusstvo”, Sostakovic dichiarava il proprio amore per Katerina Lvovna Izmajlova, la protagonista dell’opera che egli stava scrivendo da oltre venti mesi, e che vedrà la luce al Teatro Malyi di Leningrado il 22 gennaio 1934. Katerina è una ragazza russa della stessa età del compositore, ventiquattro, venticinque anni (la maturazione artistica di Sostakovic fu, com’è noto, precocissima), “dotata, intelligente e superiore alla media, la quale rovina la propria vita a causa dell’opprimente posizione cui la Russia prerivoluzionaria la assoggetta”. E’ un’omicida, anzi un vero e proprio serial killer al femminile; e tuttavia Sostakovic denuncia quanta simpatia provi per lei. Nelle originarie intenzioni dell’autore, “Una Lady Macbeth del distretto di Mcensk” avrebbe inaugurato una trilogia dedicata alla donna russa, còlta nella sua essenza immutabile attraverso differenti epoche storiche. -

Max Reger's Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Carole Terry, Chair Jonathan Bernard Craig Sheppard Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2019 Wyatt Smith ii University of Washington Abstract Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Carole Terry School of Music The history and performance of transcriptions of works by other composers is vast, largely stemming from the Romantic period and forward, though there are examples of such practices in earlier musical periods. In particular, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach found its way to prominence through composers’ pens during the Romantic era, often in the form of transcriptions for solo piano recitals. One major figure in this regard is the German Romantic composer and organist Max Reger. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Reger produced many adaptations of works by Bach, including organ works for solo piano and four-hand piano, and keyboard works for solo organ, of which there are fifteen primary adaptations for the organ. It is in these adaptations that Reger explored different ways in which to take these solo keyboard works and apply them idiomatically to the organ in varying degrees, ranging from simple transcriptions to heavily orchestrated arrangements. This dissertation will compare each of these adaptations to the original Bach work and analyze the changes made by Reger. It also seeks to fill a void in the literature on this subject, which often favors other areas of Reger’s transcription and arrangement output, primarily those for the piano. -

The Preludes in Chinese Style

The Preludes in Chinese Style: Three Selected Piano Preludes from Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi and Zhang Shuai to Exemplify the Varieties of Chinese Piano Preludes D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jingbei Li, D.M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven M. Glaser, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Edward Bak Copyrighted by Jingbei Li, D.M.A 2019 ABSTRACT The piano was first introduced to China in the early part of the twentieth century. Perhaps as a result of this short history, European-derived styles and techniques influenced Chinese composers in developing their own compositional styles for the piano by combining European compositional forms and techniques with Chinese materials and approaches. In this document, my focus is on Chinese piano preludes and their development. Having performed the complete Debussy Preludes Book II on my final doctoral recital, I became interested in comprehensively exploring the genre for it has been utilized by many Chinese composers. This document will take a close look in the way that three modern Chinese composers have adapted their own compositional styles to the genre. Composers Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi, and Zhang Shuai, while prominent in their homeland, are relatively unknown outside China. The Three Piano Preludes by Ding Shan-de, The Piano Preludes and Fugues by Chen Ming-zhi and The Three Preludes for Piano by Zhang Shuai are three popular works which exhibit Chinese musical idioms and demonstrate the variety of approaches to the genre of the piano prelude bridging the twentieth century. -

Music Certificate Repertoire Lists: Piano

MUSIC CERTIFICATE REPERTOIRE LISTS: PIANO FOUNDATION 1. J S Bach Prelude in C minor BWV999 Any reliable edition Bartok A Joke (also called Jest), no.27 from For 2. Bartók Faber Children vol.1 (from Keynotes Grades 2-3) 3. Bartók Minuet (from The First Term at the Piano) Any reliable edition 4. Beach Weaving Song (from Fingerprints) Faber 5. Beethoven Allemande in A, WoO 81 Any reliable edition 6. Beethoven Fur Elise (complete) Any reliable edition Broekmans & van 7. Cimarosa Sonata no.1 (from 11 Sonatas book 1) Poppel 8. Clementi Sonatina in C op.36 no.3, 3rd movt Any reliable edition 9. Einaudi Le Onde Any reliable edition 10. Gallupi Allegro from Sonata no.26 in A Any reliable edition 11. Gurlitt Allegretto (from Sonatina in G) Any reliable edition 12. Harris Twilight (from Fingerprints) Faber Capriccio (from Succeeding with the Masters: 13. Hässler FJH Music Company The Festival Collection book 4) Allegro (4th movt from Piano Sonata in G Hob. 14. Haydn Any reliable edition XVI/8) Haydn arr. 15. Vivace (from Finale to Symphony no.96 in D) Any reliable edition Salomon Easy improvisation no.1 (from 13 Easy Broekmans & van 16. Hengeveld Improvisations) Poppel Andante Cantabile (from Sonatina in G op. 55 17. Kuhlau Kjos KJ15968 no.2) (from Sonatinas op.20 & op.55) Marching Tune (lower version) (from Keynotes 18. Lenehan Faber Grades 1-2) 19. L Mozart Allegro in G (no.41 from Notebook for Nannerl) Any reliable edition Andante no.37 from The Chelsea Notebook 20. Mozart Faber (from Keynotes Grades 2-3) Any Performance Etude (with improvisation) (from American Popular Piano Book 3 - Etudes Novus Via 21.