Orpheu Et Al. Modernism, Women, and the War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ezra Pound His Metric and Poetry Books by Ezra Pound

EZRA POUND HIS METRIC AND POETRY BOOKS BY EZRA POUND PROVENÇA, being poems selected from Personae, Exultations, and Canzoniere. (Small, Maynard, Boston, 1910) THE SPIRIT OF ROMANCE: An attempt to define somewhat the charm of the pre-renaissance literature of Latin-Europe. (Dent, London, 1910; and Dutton, New York) THE SONNETS AND BALLATE OF GUIDO CAVALCANTI. (Small, Maynard, Boston, 1912) RIPOSTES. (Swift, London, 1912; and Mathews, London, 1913) DES IMAGISTES: An anthology of the Imagists, Ezra Pound, Aldington, Amy Lowell, Ford Maddox Hueffer, and others GAUDIER-BRZESKA: A memoir. (John Lane, London and New York, 1916) NOH: A study of the Classical Stage of Japan with Ernest Fenollosa. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1917; and Macmillan, London, 1917) LUSTRA with Earlier Poems. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1917) PAVANNES AHD DIVISIONS. (Prose. In preparation: Alfred A. Knopf, New York) EZRA POUND HIS METRIC AND POETRY I "All talk on modern poetry, by people who know," wrote Mr. Carl Sandburg in _Poetry_, "ends with dragging in Ezra Pound somewhere. He may be named only to be cursed as wanton and mocker, poseur, trifler and vagrant. Or he may be classed as filling a niche today like that of Keats in a preceding epoch. The point is, he will be mentioned." This is a simple statement of fact. But though Mr. Pound is well known, even having been the victim of interviews for Sunday papers, it does not follow that his work is thoroughly known. There are twenty people who have their opinion of him for every one who has read his writings with any care. -

2009 Program Book

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN GHALLL OHF FAFME 2009 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Dana V. Starks Mayor Chairman and Commissioner Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues William W. Greaves, Ph.D. Director/Community Liaison COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, Suite 300 Chicago, Illinois 60654-3478 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) © 2009 Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame In Memoriam Robert Maddox Tony Midnite 2 3 4 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (now the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, their organizations and their friends, as well as their contributions to the LGBT communities and to the city of Chicago. -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

2016 Program Book

2016 INDUCTION CEREMONY Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame Gary G. Chichester Mary F. Morten Co-Chairperson Co-Chairperson Israel Wright Executive Director In Partnership with the CITY OF CHICAGO • COMMISSION ON HUMAN RELATIONS Rahm Emanuel Mona Noriega Mayor Chairman and Commissioner COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST Published by Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame 3712 North Broadway, #637 Chicago, Illinois 60613-4235 773-281-5095 [email protected] ©2016 Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame In Memoriam The Reverend Gregory R. Dell Katherine “Kit” Duffy Adrienne J. Goodman Marie J. Kuda Mary D. Powers 2 3 4 CHICAGO LGBT HALL OF FAME The Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame (formerly the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame) is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, its Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (later the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame (changed to the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 2015) in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. Today, after the advisory council’s abolition and in partnership with the City, the Hall of Fame is in the custody of Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame, an Illinois not- for-profit corporation with a recognized charitable tax-deductible status under Internal Revenue Code section 501(c)(3). -

Modem Women's Poetry 1910—1929

Modem Women’s Poetry 1910—1929 Jane Dowson Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester. 1998 UMI Number: U117004 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U117004 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Modern Women9s Poetry 1910-1929 Jane Dowson Abstract In tracing the publications and publishing initiatives of early twentieth-century women poets in Britain, this thesis reviews their work in the context of a male-dominated literary environment and the cultural shifts relating to the First World War, women’s suffrage and the growth of popular culture. The first two chapters outline a climate of new rights and opportunities in which women became public poets for the first time. They ran printing presses and bookshops, edited magazines and wrote criticism. They aimed to align themselves with a male tradition which excluded them and insisted upon their difference. Defining themselves antithetically to the mythologised poetess of the nineteenth century and popular verse, they developed strategies for disguising their gender through indeterminate speakers, fictional dramatisations or anti-realist subversions. -

Communal Formations: Development of Gendered Identities

COMMUNAL FORMATIONS: DEVELOPMENT OF GENDERED IDENTITIES IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY WOMEN’ S PERIODICALS A Dissertation by by EMILY ANNE JANDA MONTEIRO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Katherine Kelly Committee Members, Marian Eide Claudia Nelson Cynthia Bouton Head of Department, Nancy Warren May 2013 Major Subject: English Copyright 2013 Emily Anne Janda Monteiro ABSTRACT Women’s periodicals at the start of the twentieth-century were not just recorders but also producers of social and cultural change. They can be considered to both represent and construct gender codes, offering readers constantly evolving communal identities. This dissertation asserts that the periodical genre is a valuable resource in the investigation of communal identity formation and seeks to reclaim for historians of British modernist feminism a neglected publication format of the early twentieth century. I explore the discursive space of three unique women’s periodicals, Bean na hÉireann, the Freewoman, and Indian Ladies Magazine, and argue that these publications exemplify the importance of the early twentieth-century British woman’s magazine-format periodical as a primary vehicle for the communication of feminist opinions. In order to interrogate how the dynamic nature of each periodical is reflected and reinforced in each issue, I rely upon a tradition of critical discourse analysis that evaluates the meaning created within and between printed columns, news articles, serial fiction, poetry, and short sketches within each publication. These items are found to be both representative of a similar value of open and frank discourse on all matters of gender subordination at that time and yet unique to each community of readers, contributors and editors. -

Barbara Grier--Naiad Press Collection

BARBARA GRIER—NAIAD PRESS COLLECTION 1956-1999 Collection number: GLC 30 The James C. Hormel Gay and Lesbian Center San Francisco Public Library 2003 Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection GLC 30 p. 2 Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p. 3-4 Biography and Corporate History p. 5-6 Scope and Content p. 6 Series Descriptions p. 7-10 Container Listing p. 11-64 Series 1: Naiad Press Correspondence, 1971-1994 p. 11-19 Series 2: Naiad Press Author Files, 1972-1999 p. 20-30 Series 3: Naiad Press Publications, 1975-1994 p. 31-32 Series 4: Naiad Press Subject Files, 1973-1994 p. 33-34 Series 5: Grier Correspondence, 1956-1992 p. 35-39 Series 6: Grier Manuscripts, 1958-1989 p. 40 Series 7: Grier Subject Files, 1965-1990 p. 41-42 Series 8: Works by Others, 1930s-1990s p. 43-46 a. Printed Works by Others, 1930s-1990s p. 43 b. Manuscripts by Others, 1960-1991 p. 43-46 Series 9: Audio-Visual Material, 1983-1990 p. 47-53 Series 10: Memorabilia p. 54-64 Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection GLC 30 p. 3 Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library INTRODUCTION Provenance The Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection was donated to the San Francisco Public Library by the Library Foundation of San Francisco in June 1992. Funding Funding for the processing was provided by a grant from the Library Foundation of San Francisco. Access The collection is open for research and available in the San Francisco History Center on the 6th Floor of the Main Library. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

'Free from All Uninvited Touch of Man”: Women's Campaigns Around Sexuality, 1880-1914

0277-5395/82/06%29%17$3.00/0 C 1982Pergamon Press Ltd. ‘FREE FROM ALL UNINVITED TOUCH OF MAN”: WOMEN’S CAMPAIGNS AROUND SEXUALITY, 1880-1914 SHEILA JFFFREYS 25A Borneo Street, London SW15 IQQ, U.K. Biographical note Sheila Jeffreys’ research on feminism, sexuality and sex reform from 1880 to 1930 has been carried out as a postgraduate student in the Department of Applied Social Studies in the University of Bradford. She is a revolutionary feminist and has been active for several years in the Women’s Liberation Movement campaigns against male violence. She is presently a member of Women Against Violence Against Women. Synopsis--The history of sex in the last 100 years has generally been represented as a triumphant march from Victorian prudery into the light ofsexual freedom. From a feminist perspective the picture is different. During the last wave of feminism women, often represented as prudes and puritans by historians, waged a massive campaign to transform male sexual behaviour in the interests of women. They campaigned against the abuse of women in prostitution, the sexual abuse of children, and marital rape. This article describes the women’s activities in the social purity movement, and the increasingly militant stance taken by some pre-war feminists who refused to relate sexually to men, in the context of the developing feminist analysis of sexuality. The main purpose of the paper is to show that in order to understand the significance of this aspect of the women’s movement we must look at the area ofsexuality not merely as a sphere of personal fulfilment but as an arena of struggle in which male dominance and women’s subordination can be most powerfully reinforced and maintained or fundamentally challenged. -

Art and Technology Between the Usa and the Ussr, 1926 to 1933

THE AMERIKA MACHINE: ART AND TECHNOLOGY BETWEEN THE USA AND THE USSR, 1926 TO 1933. BARNABY EMMETT HARAN PHD THESIS 2008 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ANDREW HEMINGWAY UMI Number: U591491 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591491 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Bamaby Emmett Haran, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis concerns the meeting of art and technology in the cultural arena of the American avant-garde during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It assesses the impact of Russian technological Modernism, especially Constructivism, in the United States, chiefly in New York where it was disseminated, mimicked, and redefined. It is based on the paradox that Americans travelling to Europe and Russia on cultural pilgrimages to escape America were greeted with ‘Amerikanismus’ and ‘Amerikanizm’, where America represented the vanguard of technological modernity. -

The Little Review, Vol. 3, No. 6

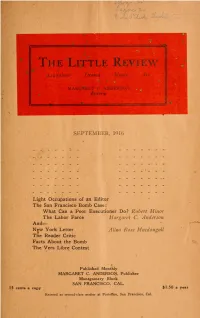

THE LITTLE REVIEW LITERATURE DRAMA MUSIC ART Margaret C. Anderson Editor SEPTEMBER, 1916 Light Occupations of an Editor The San Francisco Bomb Case: What Can a Poor Executioner Do? Robert Minor The Labor Farce Margaret C. Anderson And— New York Letter Allan Ross Macdougall The Reader Critic Facts About the Bomb The Vers Libre Contest Published Monthly MARGARET C. ANDERSON, Publisher Montgomery Block SAN FRANCISCO, CAL. 15 cents a copy $1.50 a year Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, San Francisco. Cal. The Vers Libre Contest The poems published in the Vers Libre Contest are now being considered by the judges. There were two hundred and two poems, thirty-two. of which were re- turned because they were either Shakespearean sonnets or rhymed quatrains or couplets. Manuscripts will be returned as promptly as they are rejected, providing the contestants sent postage. We hope to announce the results in our October issue, and publish the prize poems. —The Contest Editor. IN BOOKS Anything that's Radical MAY be found at McDevitt's Book Omnorium » 1346 Fillmore Street and 2079 Sutter Street San Francisco, California (He Sells The Little Review, Too) THE LITTLE REVIEW VOL III. SEPTEMBER, 1916 NO. 6 The Little Review hopes to become a magazine of Art. The September issue is offered as a Want Ad. Copyright, 1916, by Margaret C. Anderson 2 The Little Reviev . "The other pages will be left blank." The Little Review 3 The Little Review 4 The Little Review 5 The Little Review 6 The Little Review 7 The Little Review 8 The Little Review 9 The Little Review 10 The Little Review 11 The Little Review 14 The Little Review 13 14 The Little Review SHE PRACTICES EIGHTEEN HOURS A DAY AND- BREAKFASTING CONVERTING THE SHERIFF TO ANARCHISM AND VERS LIBRE - TAKES HER MASON AND HAMLIN TO BED WITH HER SUFFERING FOR HUMANITY AT EMMA GOLDMAN'S LECTURES Light occupations of the editor The Little Review 15 GATHERING HER OWN FIRE-WOOO THE STEED on WHICH SHE HAS SWIMMING HER PICTURE TAKEN THE INSECT ON WHICH SHE RIDES while there is nothing to edit. -

The Little Review and Modernist Salon Culture

MA MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER "Conversations That Fly": The Little Review and Modernist Salon Culture RON LEVY -, Supervisor: Dr. Irene Gammel Reader: Dr. Elizabeth Podnieks The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joint Graduate Program in Communication & Culture Ryerson University - York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada January 2010 Levy 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Irene Gammel for introducing me, through her course CC8938: Modernist Literary Circles: A Cultural Approach, to the Little Review. The personalities that populated the pages of this historically important literary journal practically leapt off the page and attracted me to learn more. Dr. Gammel's enthusiastic and patient guidance made it possible for me to learn about a subject that greatly interests me- the power oftalk - and to challenge myself to reach new levels of research and writing. Unexpectedly, this project also helped me to learn about myself. I found many similarities between my experiences communicating and debating sometimes unpopular beliefs and those of Margaret Anderson, one of the central subjects of this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Podnieks for providing helpful and detailed feedback at short notice, all of which have found their way into this MRP and have further improved this project, as well as for introducing me, through her course CC30: Writing the Self, Reading the Lifo, to theories that relate to the autobiographical genre. Finally, I would like to thank the Joint Graduate Program in Communication and Culture for giving me this incredible experience to step into so many new worlds of thinking.