The Era of the Three Kingdoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 48. Last

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 48. Last time, Sun Quan and the troops of the Southlands had just defeated and killed Huang (2) Zu (3), a close friend and top commander of Liu Biao, the imperial protector of Jing (1) Province. Sun Quan had also captured the key city of Jiangxia (1,4), which Huang Zu was defending. Upon receiving Huang Zu’s head, Sun Quan ordered that it be placed in a wooden box and taken back to the Southlands to be placed as an offering at the altar of his father, who had been killed in battle against Liu Biao years earlier. He then rewarded his troops handsomely, promoted Gan Ning, the man who defected from Huang Zu and then killed him in battle, to district commander, and began discussion of whether to leave troops to garrison the newly conquered city. His adviser Zhang Zhao (1), however, said, “A lone city so far from our territory is impossible to hold. We should return to the Southlands. When Liu Biao finds out we have killed Huang Zu, he will surely come looking for revenge. We should rest our troops while he overextends his. This will guarantee victory. We can then attack him as he falls back and take Jing Province.” Sun Quan took this advice and abandoned his new conquest and returned home. But there was still the matter of Su (1) Fei (1), the enemy general he had captured. This Su Fei was friends with Gan Ning and was actually the one who helped him defect to Sun Quan. -

The Congregation of Heroes: a Skyrim Representation

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 4-2017 The onC gregation of Heroes: A Skyrim Representation Richard Smith DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Richard, "The onC gregation of Heroes: A Skyrim Representation" (2017). Student research. 77. http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch/77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Congregation of Heroes: A Skyrim Representation Richard Smith Honor Scholar Program Senior Project 2017 Sponsor: Dr. Dave Berque First Reader: Dr. Sherry Mou Second Reader: Dr. Harry Brown 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 A Brief History 4 The Congregation of Heroes 6 Thesis Project 8 Skyrim and the Creation Kit 9 The Creation Process 10 Creative Decisions for the First Iteration 14 Technical Details for the First Iteration 18 The User Study 20 The Second Iteration 23 The Ethics of Translation 26 Conclusion 28 Acknowledgements 30 Works Cited 31 2 3 A Brief History The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is a novel detailing the events during the final years of the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period. This time period, approximately 169 AD to 280 AD (Luo), was notable for the constant power struggles between the three kingdoms in China at the time. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 3. Before

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 3. Before we pick up where we left off, I have a quick programming note for those of you who haven’t seen it on the website yet. I have decided to scale back the length of the episodes. Each of the first two episodes came in at nearly 40 minutes, and it felt long when I was writing them, recording them, editing them, and listening to them. When I am talking from a script for a long time, I have a tendency to fall back into reading rather than talking, and I want to avoid that. So I am going to try to keep future episodes to between 25 and 30 minutes. I think that will make the episodes easier for me to produce and result in a better product for you. It does mean that it will take longer to get through the whole novel, but hey, when your project starts out being at least a three-year commitment, what’s a few more months? So anyway, back to the story. At the end of the last episode, we were knee-deep in palace intrigue as a power struggle had broken out at the very top of the empire. Emperor Ling had just died. He had two sons, and both them were just kids at this point. The eunuchs were planning to make one son, prince Liu Xie (2), the heir, but the regent marshall, He Jin, the brother of the empress, beat them to the punch and declared her son, prince Liu Bian (4), the new emperor. -

Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5

JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 Cao Cao Dossier 曹操 Crisis Director: Matthew Owens, Charles Miller Email: [email protected], [email protected] Chair: Harjot Singh Email: [email protected] Table of Contents: 1. Front Page (Page 1) 2. Table of Contents (Page 2) 3. Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier (Pages 3-4) 4. Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5. Cao Zhang (Pages 7-8) 6. Cao Zhi (Pages 9-10) 7. Lady Bian (Page 11) 8. Emperor Xian of Han (Pages 12-13) 9. Empress Fu Shou (Pages 14-15) 10. Cao Ren (Pages 16-17) 11. Cao Hong (Pages 18-19) 12. Xun Yu (Pages 20-21) 13. Sima Yi (Pages 22-23) 14. Zhang Liao (Pages 24-25) 15. Xiahou Yuan (Pages 26-27) 16. Xiahou Dun (Pages 28-29) 17. Yue Jin (Pages 30-31) 18. Dong Zhao (Pages 32-33) 19. Xu Huang (Pages 34-35) 20. Cheng Yu (Pages 36-37) 21. Cai Yan (Page 38) 22. Han Ji (Pages 39-40) 23. Su Ze (Pages 41-42) 24. Works Cited (Pages 43-) Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier: Most characters within the Court of Cao Cao are either generals, strategists, administrators, or family members. ● Generals lead troops on the battlefield by both developing successful battlefield tactics and using their martial prowess with skills including swordsmanship and archery to duel opposing generals and officers in single combat. They also manage their armies- comprising of troops infantrymen who fight on foot, cavalrymen who fight on horseback, charioteers who fight using horse-drawn chariots, artillerymen who use long-ranged artillery, and sailors and marines who fight using wooden ships- through actions such as recruitment, collection of food and supplies, and training exercises to ensure that their soldiers are well-trained, well-fed, well-armed, and well-supplied. -

IEA) 2012 Volume 4 Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering

Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering 219 Zhicai Zhong Editor Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Engineering and Applications (IEA) 2012 Volume 4 Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering Volume 219 For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7818 Zhicai Zhong Editor Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Engineering and Applications (IEA) 2012 Volume 4 123 Editor Zhicai Zhong Chongqing People’s Republic of China ISSN 1876-1100 ISSN 1876-1119 (electronic) ISBN 978-1-4471-4852-4 ISBN 978-1-4471-4853-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4471-4853-1 Springer London Heidelberg New York Dordrecht Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956302 Ó Springer-Verlag London 2013 MATLAB and Simulink are registered trademarks of The MathWorks, Inc. See www.mathworks.com/ trademarks for a list of additional trademarks. Other product or brand names may be trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. Amazon is a trademark of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates. Google is a trademark of Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, U.S.A http://www.google.com This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, reci- tation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief ex- cerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

三國演義 Court of Liu Bei 劉備法院

JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 Court of Liu Bei 劉備法院 Crisis Directors: Matthew Owens, Charles Miller Emails: [email protected], [email protected] Chair: Isis Mosqueda Email: [email protected] Single-Delegate: Maximum 20 Positions Table of Contents: 1. Title Page (Page 1) 2. Table of Contents (Page 2) 3. Chair Introduction Page (Page 3) 4. Crisis Director Introduction Pages (Pages 4-5) 5. Intro to JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Pages 6-9) 6. Intro to Liu Bei (Pages 10-11) 7. Topic History: Jing Province (Pages 12-14) 8. Perspective (Pages 15-16) 9. Current Situation (Pages 17-19) 10. Maps of the Middle Kingdom / China (Pages 20-21) 11. Liu Bei’s Domain Statistics (Page 22) 12. Guiding Questions (Pages 22-23) 13. Resources for Further Research (Page 23) 14. Works Cited (Pages 24-) Dear delegates, I am honored to welcome you all to the Twenty Ninth Mid-Atlantic Simulation of the United Nations Conference, and I am pleased to welcome you to JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Everyone at MASUN XXIX have been working hard to ensure that this committee and this conference will be successful for you, and we will continue to do so all weekend. My name is Isis Mosqueda and I am recent George Mason Alumna. I am also a former GMU Model United Nations president, treasurer and member, as well as a former MASUN Director General. I graduated last May with a B.A. in Government and International politics with a minor in Legal Studies. I am currently an academic intern for the Smithsonian Institution, working for the National Air and Space Museum’s Education Department, and a substitute teacher for Loudoun County Public Schools. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

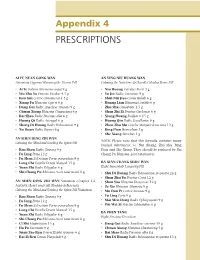

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS AI FU NUAN GONG WAN AN YING NIU HUANG WAN Artemisia-Cyperus Warming the Uterus Pill Calming the Nutritive-Qi [Level] Calculus Bovis Pill • Ai Ye Folium Artemisiae argyi 9 g • Niu Huang Calculus Bovis 3 g • Wu Zhu Yu Fructus Evodiae 4.5 g • Yu Jin Radix Curcumae 9 g • Rou Gui Cortex Cinnamomi 4.5 g • Shui Niu Jiao Cornu Bubali 6 g • Xiang Fu Rhizoma Cyperi 9 g • Huang Lian Rhizoma Coptidis 6 g • Dang Gui Radix Angelicae sinensis 9 g • Zhu Sha Cinnabaris 1.5 g • Chuan Xiong Rhizoma Chuanxiong 6 g • Shan Zhi Zi Fructus Gardeniae 6 g • Bai Shao Radix Paeoniae alba 6 g • Xiong Huang Realgar 0.15 g • Huang Qi Radix Astragali 6 g • Huang Qin Radix Scutellariae 9 g • Sheng Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae 9 g • Zhen Zhu Mu Concha Margatiriferae usta 12 g • Xu Duan Radix Dipsaci 6 g • Bing Pian Borneolum 3 g • She Xiang Moschus 1 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN NOTE: Please note that this formula contains many Calming the Mind and Settling the Spirit Pill banned substances, i.e. Niu Huang, Zhu Sha, Bing • Ren Shen Radix Ginseng 9 g Pian and She Xiang. They should be replaced by Shi • Fu Ling Poria 12 g Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. • Fu Shen Sclerotium Poriae pararadicis 9 g • Long Chi Fossilia Dentis Mastodi 15 g BA XIAN CHANG SHOU WAN • Yuan Zhi Radix Polygalae 6 g Eight Immortals Longevity Pill • Shi Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii 8 g • Shu Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae preparata 24 g • Shan Zhu Yu Fructus Corni 12 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN Variation (Chapter 14, • Shan Yao Rhizoma Dioscoreae 12 g Anxiety, Heart and Gall Bladder -

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is a Supplemental Episode. Alright, So This Is Another Big One, As We

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is a supplemental episode. Alright, so this is another big one, as we bid farewell to the novel’s main protagonist, Liu Bei. In the novel, he is portrayed as the ideal Confucian ruler, extolled for his virtue, compassion, kindness, and honor, as well as his eagerness for seeking out men of talent. How much of that is actually true? Well, we’ll see. But bear in mind that even the source material we have about Liu Bei should be considered heavily biased, since the main historical source we have, the Records of the Three Kingdoms, was written by a guy who had served in the court of the kingdom that Liu Bei founded, which no doubt colored his view of the man. Given Liu Bei’s eventual status as the emperor of a kingdom, there were, unsurprisingly, very extensive records about his life and career, and what’s laid out in the novel In terms of the whens, wheres, and whats of Liu Bei’s life pretty much corresponds with real-life events. Because of that, I’m not going to do a straight rehash of his life since that alone would take two full episodes. Seriously, I had to rewrite this episode three times to make it a manageable length, which is why it’s being released a month later than I anticipated. So instead, I’m going to pick and choose from the notable stories about Liu Bei from the novel and talk about which ones were real and which ones were pure fiction. -

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People's Commune

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People’s Commune: Amateurism and Social Reproduction in the Maoist Countryside by Angie Baecker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Asian Languages and Cultures) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Xiaobing Tang, Co-Chair, Chinese University of Hong Kong Associate Professor Emily Wilcox, Co-Chair Professor Geoff Eley Professor Rebecca Karl, New York University Associate Professor Youngju Ryu Angie Baecker [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0182-0257 © Angie Baecker 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother, Chang-chang Feng 馮張章 (1921– 2016). In her life, she chose for herself the penname Zhang Yuhuan 張宇寰. She remains my guiding star. ii Acknowledgements Nobody writes a dissertation alone, and many people’s labor has facilitated my own. My scholarship has been borne by a great many networks of support, both formal and informal, and indeed it would go against the principles of my work to believe that I have been able to come this far all on my own. Many of the people and systems that have enabled me to complete my dissertation remain invisible to me, and I will only ever be able to make a partial account of all of the support I have received, which is as follows: Thanks go first to the members of my committee. To Xiaobing Tang, I am grateful above all for believing in me. Texts that we have read together in numerous courses and conversations remain cornerstones of my thinking. He has always greeted my most ambitious arguments with enthusiasm, and has pushed me to reach for higher levels of achievement. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 10

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 10. So hey, we made it into double digits on the episode count. I think that calls for a minor celebration. If we were in the era of the Three Kingdoms, this would be where I get up, bow, and offer you all a cup of wine to show my gratitude for your support. Thank you to everyone who has given this podcast a little bit of your time and attention. My podcast stats tell me that the show’s audience is growing, and I thank those of you who have been spreading the word. If you know someone who might be interested in this show, point them to our website, 3kingdomspodcast.com, spelled with the number 3. Also, don’t forget to check out our Twitter feed and Google Plus page, where I post updates and miscellaneous information related to the show. The links are on the website. Thanks! Now let’s get on with the show. Last time on the podcast, Sun Jian had set off on an expedition to seek revenge against Liu Biao for an earlier unprovoked attack when Sun Jian was returning home with the imperial hereditary seal. The campaign could not have gotten off to a better start. Sun Jian easily foiled the defenses set up by Liu Biao’s commander Huang (2) Zu (3), and then soundly defeated Huang (2) Zu (3) in a pitch battle. With the opposition on the run, Sun Jian began to advance on Xiangyang Prefecture (1,2), which was Liu Biao’s home base. -

A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments

2011 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (iCBBE 2011) Wuhan, China 10 - 12 May 2011 Pages 1 - 867 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1129C-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-5088-6 1/7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ALGORITHMS, MODELS, SOFTWARE AND TOOLS IN BIOINFORMATICS: A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments ............................................................1 Hongbin Lee, Bo Wang, Xiaoming Wu, Yonggang Liu, Wei Gao, Huili Li, Xu Wang, Feng He A New Promoter Recognition Method Based On Features Optimal Selection.................................................................5 Lan Tao, Huakui Chen, Yanmeng Xu, Zexuan Zhu A Center Closeness Algorithm For The Analyses Of Gene Expression Data ...................................................................9 Huakun Wang, Lixin Feng, Zhou Ying, Zhang Xu, Zhenzhen Wang A Novel Method For Lysine Acetylation Sites Prediction ................................................................................................ 11 Yongchun Gao, Wei Chen Weighted Maximum Margin Criterion Method: Application To Proteomic Peptide Profile ....................................... 15 Xiao Li Yang, Qiong He, Si Ya Yang, Li Liu Ectopic Expression Of Tim-3 Induces Tumor-Specific Antitumor Immunity................................................................ 19 Osama A. O. Elhag, Xiaojing Hu, Weiying Zhang, Li Xiong, Yongze Yuan, Lingfeng Deng, Deli Liu, Yingle Liu, Hui Geng Small-World Network Properties Of Protein Complexes: Node Centrality And Community Structure