Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Krigsdagbocker 1939-1945 By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ref. # Lang. Section Title Author Date Loaned Keywords 6437 Cg Kristen Liv En Bro Til Alle Folk Dahl, Øyvind 1981

Lang. Section Title Author Date Loaned Keywords Ref. # 6437 cg Kristen liv En bro til alle folk Dahl, Øyvind 1981 ><'14/11/19 D Dansk Mens England sov Churchill, Winston S. 1939 Arms and the 3725 Covenant D Dansk Gourmet fra hummer a la carte til æg med Lademann, Rigor Bagger 1978 om god vin og 4475 kaviar (oversat og bearbejdet af) festlig mad 7059 E Art Swedish Silver Andrén, Erik 1950 5221 E Art Norwegian Painting: A Survey Askeland, Jan 1971 ><'06/10/21 E Art Utvald att leva Asker, Randi 1976 7289 11211 E Art Rose-painting in Norway Asker, Randi 1965 9033 E Art Fragments The Art of LLoyd Herfindahl Aurora University 1994 E Art Carl Michael Bellman, The life and songs of Austin, Britten 1967 9318 6698 E Art Stave Church Paintings Blindheim, Martin 1965 7749 E Art Folk dances of Scand Duggan, Anne Schley et al 1948 9293 E Art Art in Sweden Engblom, Sören 1999 contemporary E Art Treasures of early Sweden Gidlunds Statens historiska klenoder ur 9281 museum äldre svensk historia 5964 E Art Another light Granath, Olle 1982 9468 E Art Joe Hills Sånger Kokk, Enn (redaktør) 1980 7290 E Art Carl Larsson's Home Larsson, Carl 1978 >'04/09/24 E Art Norwegian Rosemaling Miller, Margaret M. and 1974 >'07/12/18 7363 Sigmund Aarseth E Art Ancient Norwegian Design Museum of National 1961 ><'14/04/19 10658 Antiquities, Oslo E Art Norwegian folk art Nelson, Marion, Editor 1995 the migration of 9822 a tradition E Art Döderhultarn Qvist, Sif 1981? ><'15/07/15 9317 10181 E Art The Norwegian crown regalia risåsen, Geir Thomas 2006 9823 E Art Edvard Munck - Landscapes of the mind Sohlberg, Harald 1995 7060 E Art Swedish Glass Steenberg, Elisa 1950 E Art Folk Arts of Norway Stewart, Janice S. -

The Need for Global Literature

1 The Need for Global Literature ardening and cooking: These topics often bring pleasure, as Gmost of us love food, and virtually every culture has its delec - table specialties. Many people enjoy and take pride in raising their own produce; for some, it is a necessity. The late 1990s saw the pub - lication of four children’s books that used these motifs to demon - strate and celebrate the diversity of our society. In Erika Tamar’s (1996) Garden of Happiness , the Lower East Side of New York City becomes the setting of a community garden for Puerto Rican, African American, Indian, Polish, Kansan, and Mexican neighbors. In Seedfolks, by Paul Fleischman (1997), a Cleveland, Ohio, neigh - borhood garden brings together 13 strangers from Vietnamese, Rumanian, white Kentuckian, Guatemalan, African American, Jewish, Haitian, Korean, British, Mexican, and Indian backgrounds. Mama Provi and the Pot of Rice, by Sylvia Rosa-Casanova (1997), por - trays how a Puerto Rican grandmother’s pot of arroz con pollo trans - forms into a multicultural feast with the help of white, Italian, black, and Chinese neighbors in one city apartment building. Another urban dwelling forms the setting in Judy Cox’s (1998) Now We Can Have a Wedding! when Jewish, Japanese, Chinese, Italian, and Russian neighbors contribute to a multicultural banquet for a Greek-Mexican wedding. 4 The Need for Global Literature 5 Cities in the United States often are the places where small com - munities encompass such diverse cultures, so perhaps it is unsurpris - ing that these four books use similar premises. In addition, according to U.S. -

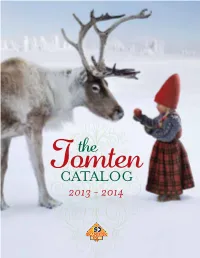

Tomten Catalog Is Produced by Skandisk, Inc

the TomtenCATALOG 2013 - 2014 CHRISTMAS BOOKS FOR ALL AGES Christmas Cards Notecards page 6 page 32 Little Tomte’s Christmas Wish Santa Claus and the Three Bears by Inkeri Karvonen Illustrated by Hannu Taina by Maria Modugno Illustrated by Jane & Brook Dyer The Christmas Wish by Lori Evert & Per Breiehagen Little Tomte embarks on a candle-making plan When Papa Bear, Mama Bear, and Baby Bear return from “The tale follows Anja as she ventures through ice and snow on skis, aided to help his Christmas wish come true. Children a snowy stroll on Christmas Eve, they are surprised at what by several animals, to find Santa Claus.”—Publishers Weekly will enjoy this heartwarming festive tale from they find. This book positively glows with warmth and humor. Hardcover. $17.99 CHR 600 Finland. Ages 4-10. Hardcover. Hardcover. $17.99 CHR 604 $17.95 CHR 603 Snow Bunny’s Christmas Wish The Tomtes’ Christmas Porridge The Christmas Angels The Sparkle Box by Jill Hardie by Rebecca Harry by Sven Nordqvist by Else Wenz Viëtor The moving story of an uncommon gift and The only present Snow Bunny truly wants When the family forgets to leave porridge for On Christmas Eve the Christmas angels fly how giving to others shows a little boy the for Christmas is a friend. Can Santa make the tomtes on Christmas Eve, Mama tomte down to help those in need. First published in true meaning of Christmas. Includes a glitter- her wish come true? Dazzling foil effects hatches a plan before Papa tomte finds out! Germany in 1933, this beautiful book features coated fold-out Sparkle Box! Ages 4-8. -

L Vimmerby Kommun

Vimmerby TJÄNSTES~VELSE 1(4) kommun 2017-02-07 l 2015/335 Kommunstyrelseförvaltningen SS J IJ PO Kommunstyrelsen Avtal mellan Vimmerby kommun, Vimmerby kommun Förvaltnings AB, Kul turkvarteret Astrid Lindgrens Näs AB, Astrid Lindgrens Värld AB, Insam lingsstiftelsen för bevarandet av Astrid Lindgrens gärning m fl om överlåtel• se av aktier i Kulturkvarteret Astrid Lindgrens Näs AB, överlåtelse av fastig heten Boken 2 och delar av fastigheten Vimmerby 3:3, m m Förslag till beslut Kommunstyrelsen föreslås i sin tur föreslå kommunfullmäktige besluta att godkänna samtliga avtal som Vimmerby kommun är part i, se punktema a, b, d, f, g och l nedan, att tillstyrka samtliga avtal som Vimmerby kommun Förvaltnings AB eller Kul turkvarteret Astrid Lindgrens Näs AB är part i, se punktema a, c, d, e, g, h, i, j och l nedan, att godkänna ny bolagsordning för Kulturkvarteret Astrid Lindgrens Näs AB, att genom gåva till Insamlingen för bevarandet av Astrid Lindgrens gärning överlåta dels ytterligare mark vid Kulturcentrumet Astrid Lindgren Näs, dels den del av fastigheten Vimmerby 3:3 som benämns Kohagen, allt under för• utsättning att detaljplaner som medger marköverlåtelserna antas och vinner laga kraft, samt att uppdra åt kommunstyrelsen att verkställa marköverlåtelserna enligt angivna förutsättningar. Bakgrund I Vimmerby, där författarinnan Astrid Lindgren föddes och växte upp, finns teater- och temaparken Astrid Lindgrens Värld som ägs av Astrid Lindgrens Värld AB ("ALV") och som årligen har ca 500 000 besökare. ALV ägs till 9,92 procent av det av Vimmerby kommun ("Kommunen") ägda bolaget Vimmerby kommun Förvaltnings AB ("VKF") och till 90,08 procent av Salikon Förvaltnings AB ("Salikon"). -

Kurslitteratur LV1500 Gäller Från VT 2021

Litteraturvetenskap Litteraturlista Astrid Lindgren. Från flickbok till fantasy, GN, 7,5 hp (LV1500) * = Tillgänglig på Athena Samtliga texter kan läsas i senare utgåvor. Primärlitteratur – litteratur av Astrid Lindgren Allrakäraste syster (1973), bilderbok med illustrationer av Hans Arnold Barnen på Bråkmakargatan (1956) Britt-Mari lättar sitt hjärta (1944) Bröderna Lejonhjärta (1973) Emil i Lönneberga (1963) Eva möter Noriko-San (1956), eller en valfri titel ur serien ”Barn i olika länder” ”Hoppa högst” (novell i Kajsa Kavat och andra barn, 1950)* ”Jag får göra som jag vill, sa prinsen” i Sagoprinsessan (1946)* Kati i Amerika (1950), eller en valfri titel i Kati-trilogin Känner du Pippi Långstrump? (1947) Madicken (1960) Mästerdetektiven Blomkvist (1946) Pippi Långstrump (1945)* Pippi Långstrump, valfri seriealbum Ronja rövardotter (1981) "Sunnanäng" (1959), novell ur novellsamlingen Sunnanäng* Sunnanäng (2003), bilderbok med illustrationer av Marit Törnqvist Ur-Pippi. Originalmanus (2007), med förord av Karin Nyman och kommentarer av Ulla Lundqvist, s. 1-10.* Vi på Saltkråkan (1964) Sekundärlitteratur Ahlbäck, Pia Maria, ”Väderkontraktet: plats, miljörättvisa och eskatologi i Astrid Lindgrens Vi på Saltkråkan”, Barnboken 2010:2, s. 5-18* Andersen, Jens, Denna dagen, ett liv: en biografi över Astrid Lindgren (Stockholm, 2019), 15 s. enligt lärarens anvisning* Andersson, Maria, "Borta bra, men hemma bäst?: Elsa Beskows och Astrid Lindgrens idyller", i Maria Andersson & Elina Druker (red.), Barnlitteraturanalyser, s. 55-70, 2008* Bohlund, Kjell, Den okända Astrid Lindgren: åren som bokförläggare och chef (Stockholm, 2018), 15 s. enligt lärarens anvisning* Druker, Elina, ”The animated still life: Ingrid Vang Nyman's use of self-contradictory spatial order in Pippi Longstocking”, Barnboken., 2007:1-2, s. -

Bildbibliografi Över Astrid Lindgrens Skrifter 1921- 2010

Skrifter utgivna av Svenska barnboksinstitutet nr 118 Lars Bengtsson Bildbibliografi över Astrid Lindgrens skrifter 1921- 2010 Salikon förlag UNIVERSITATSBlbuu I iitt\,. i. - ZENTRALBIBLIOTHEK - Innehåll Författarens förord 5 Den där Emil 183 Avd. 3: Samlingsvolymer 243 Astrid Surmatz: Draken med de röda ögonen 185 Alla mina barn 244 Bibliografi och passion 6 Emil med paltsmeten 187 Allas vår Madicken 245 Innehåll 9 Emil och soppskålen 188 Allt om Karlsson på taket 246 Eva möter Noriko-San 188 Astrid Lindgren-biblioteket 247 Avd. 1: Barn- och Ingen rövare finns i skogen 190 Barnen i Bullerbyn 248 ungdomsböcker 11 I Skymningslandet 190 Barnen på Bråkmakargatan 248 Alla vi barn i Bullerbyn 12 Jackie bor i Holland 191 Boken om Lotta på Assar Bubbla 21 fag vill inte gå och lägga mig 191 Bråkmakargatan 248 Bara roligt i Bullerbyn 23 Jag vill också gå i skolan 195 Boken om Pippi Långstrump 249 Barnen på Bråkmakargatan 27 Jag vill också ha ett syskon 197 Bröderna Lejonhjärta, Samuel Britt-Mari lättar sitt hjärta 31 Jul i Bullerbyn 199 August från Sevedstorp och Bröderna Lejonhjärta 33 Jul i stallet 201 Hanna i Hult samt Emil i Lönneberga 44 Junker Nils av Eka 202 Har boken en framtid? 253 Emils hyss nr 325 50 Kajsa Kavat hjälper mormor 202 Bullerbyboken 253 Inget knussel, sa Emil i Karlsson på taket går på Emil och Ida i Lönneberga 257 Lönneberga 52 födelsedagskalas 205 Från Pippi till Ronja 257 Jullov är ett bra påhitt, Känner du Pippi Långstrump? 206 God Jul! 259 sa Madicken 53 Lilibet cirkusbarn 209 God Jul i stugan! 259 Kajsa Kavat och andra -

Astrid Lindgren and Being Swedish Astrid Lindgren

Astrid Lindgren and Being Swedish Astrid Lindgren (1907-2002) was a children's writer of international repute. Although many of her stories are set in specific times and particular places in Sweden, her work transcends the time-bound and narrowly provincial. Her settings, be they urban, countryside, or fantastic know no borders even when they “are” Swedish down to the last nail. And, of course, outrageous and transgressive characters like Pippi Longstocking and Karlsson-on-the-roof hold no passports; they belong (and are out of place) everywhere. I believe, too, that Lindgren's oral storytelling style makes her more readily translatable into other languages and cultures than if she had used a more literary style. Finally, Lindgren’s deep concern for the vulnerable (yet potentially empowered) child finds resonance across possible cultural divides. Lindgren writes for a commonwealth of children. However, it is also true that Astrid Lindgren and her work hold a special place in the hearts and minds of Swedes. One could even argue that the collective identity formation of Swedes owes a great deal to her. The template for a good (if old-fashioned) childhood is that of the Bullerby children. Childhood pranks are inevitably compared to those of Emil. Attitudes of solidarity and courage are lent shape by Ronia and the Brother's Lionheart. The expression “han fattas mig” (feebly translated “I miss him”) is frequently seen in obituaries. Names like Ida, Emil, Annika and even the invented Ronia have acquired currency (and not only in Sweden). The The tourist board of Småland puts her name to good use; there is a Lindgren theme park in Vimmerby close to where she grew up; Stockholm has an Astrid Lindgren open-air museum (“Junibacken”). -

Astrid-Lindgren.Pdf

Astrid Lindgren en studiebok NBV lanserar studiecirkel om Astrid Lindgren! Författare Gunilla Zimmermann C 2018 författaren och NBV Foto omslag: Roine Karlsson 1 ASTRID LINDGREN -EN STUDIEBOK Anvisningar för studiearbetet Astrid Lindgren i våra hjärtan Astrid Lindgren – Sveriges främsta exportvara a) Inspirationskällor b) Motivkretsar i Astrid Lindgrens böcker c) Stilen i Astrid Lindgrens böcker Barn- och ungdomsår Idylliska barndomsskildringar a) Bullerbyböckerna b) Barnen på Bråkmakargatan c) Madicken d) Emil i Lönneberga Uppbrott från Vimmerby – Astrid Eriksson blir Astrid Lindgren Debut som författare – Flick- och ungdomsböcker a) Britt-Marie lättar sitt hjärta Kerstin och jag Katiböckerna b) Barn- och ungdomsdeckare Kalle Blomkvist Rasmus på luffen Rasmus, Pontus och Toker Pippi Långstrump – Århundradets barn a) Barnets århundrade b) Barn- och ungdomslitteratur före Pippi c) Från hugskott till världskändis d) Pippi Långstrump – en övermänniska e) Språk och stil f) Mottagandet Världens bästa Karlsson Sagorna a) Nils- Karlsson-Pyssling b) Kajsa Kavat c) Mio, min Mio d) Sunnanäng e) Bröderna Lejonhjärta f) Ronja Rövardotter Vi på Saltkråkan Astrid Lindgrens övriga författarskap 2 a) Bilderböcker b) Teaterpjäser c) Essäer d) Debattinlägg Förteckning över Astrid Lindgrens verk Vimmerby – Astrid Lindgrens stad Astrid Lindgren – vår andes stämma i världen Litteraturförteckning Förteckning över filmer 3 Anvisningar för studiecirkelarbetet Välkommen till studiecirkeln om Astrid Lindgren. Innan vi börjar ägna oss åt henne på allvar, ska vi -

Astrid Lindgren and Being Swedish

Astrid Lindgren and Being Swedish Astrid Lindgren (1907-2002) was a children's writer of international repute. Although many of her stories are set in specific times and particular places in Sweden, her work transcends the time-bound and narrowly provincial. Her settings, be they urban, countryside, or fantastic know no borders even when they “are” Swedish down to the last nail. And, of course, outrageous and transgressive characters like Pippi Longstocking and Karlsson-on-the-roof hold no passports; they belong (and are out of place) everywhere. I believe, too, that Lindgren's oral storytelling style makes her more readily translatable into other languages and cultures than if she had used a more literary style. Finally, Lindgren’s deep concern for the vulnerable (yet potentially empowered) child finds resonance across possible cultural divides. Lindgren writes for a commonwealth of children. However, it is also true that Astrid Lindgren and her work hold a special place in the hearts and minds of Swedes. One could even argue that the collective identity formation of Swedes owes a great deal to her. The template for a good (if old-fashioned) childhood is that of the Bullerby children. Childhood pranks are inevitably compared to those of Emil. Attitudes of solidarity and courage are lent shape by Ronia and the Brother's Lionheart. The expression “han fattas mig” (feebly translated “I miss him”) is frequently seen in obituaries. Names like Ida, Emil, Annika and even the invented Ronia have acquired currency (and not only in Sweden). The The tourist board of Småland puts her name to good use; there is a Lindgren theme park in Vimmerby close to where she grew up; Stockholm has an Astrid Lindgren open-air museum (“Junibacken”). -

Doreen Denning's Arkiv

Doreen Denning’s arkiv Doreen Denning 1928-2007 Skådespelerska, dubbningsregissör. Född i London, England. Avled i Kungsängen, Stockholms län. Arkivet innehåller engelska och svenska manus, trailermanus och annat material från Doreen Dennings arbete som ansvarig för svenska versioner av Disneyfilmer (och andra). Dessutom förekommer arbetsmaterial för filmernas utgivning på skiva/kassett. Arkivet är uppdelat i v. 1-26, som rör arbetet med Disney’s filmer och skivor [med undantag för v. 6 som även innehåller den danska filmen Lille Virgil…]; v. 27-30, som rör arbetet med Astrid Lindgrens filmer och skivor och v. 31-37, som rör andra filmtitlar samt övrigt material. DD: v. 1 [Pärm, orange rygg]: Aristocats (US, 1970 [Sv. 1971]). Svenskt manus, credits och biografannonser. Se även v. 19, 24. DD: v. 2 [Svart pärm]: Askungen / Cinderella (US, 1949 [Sv. 1950]) Svenskt manus. credits, anteckningar. [Oklart vad DD’s roll var här, uppgift saknas. Filmen omdubbad 1958, samt videorelease 1998.]. Se även v. 24, 26B. DD: v. 3 [Svart pärm]: Bambi (US, 1942 [Sv. 1985]). Svenskt och engelskt manus, inspelningsplan, sånger/noter, credits, trailertext. Se även v. 21. DD: v. 4 [Pärm, grön rygg]: Bernard & Bianca ; Bernard & Bianca i Australien / The Rescuers ; The rescuers down under (US , 1977 [Sv 1978, 1997 videorelease] ; (US, 1990 [Sv. 1991]) Svenska och engelska manus. Walt Disney info om filmerna samt karaktärer, bilder, sånger/noter. Tidsschema och kommentarer för röstprover, korrespondens. Bioannonser. Se även v. 23. DD: v. 5 [Pärm, gul rygg]: Dumbo [US, 1941 [Sv. 1972]). Svenskt manus. Se även v. 19. I-ors födelsedag / Winnie the Pooh and a day for Eeyore [För TV? Denna titel visad 1986-01-03 i SVT1] Svenskt manus. -

Ref. # Lang.Section Title Author Date Keywords 6437 Cg Kristen Liv En Bro Til Alle Folk Dahl, Øyvind 1981 D Dansk Mens England Sov Churchill, Winston S

Ref. # Lang.Section Title Author Date Keywords 6437 cg Kristen liv En bro til alle folk Dahl, Øyvind 1981 D Dansk Mens England sov Churchill, Winston S. 1939 Arms and the Covenant 3725 D Dansk Gourmet fra hummer a la carte til æg med kaviar Lademann, Rigor Bagger (oversat1978 ogom bearbejdet god vin ogaf) festlig 4475 mad 7059 E Art Swedish Silver Andrén, Erik 1950 5221 E Art Norwegian Painting: A Survey Askeland, Jan 1971 7289 E Art Utvald att leva Asker, Randi 1976 11211 E Art Rose-painting in Norway Asker, Randi 1965 9033 E Art Fragments The Art of LLoyd Herfindahl Aurora University 1994 9318 E Art Carl Michael Bellman, The life and songs of Austin, Britten 1967 6698 E Art Stave Church Paintings Blindheim, Martin 1965 7749 E Art Folk dances of Scand Duggan, Anne Schley et al 1948 9293 E Art Art in Sweden Engblom, Sören 1999 contemporary E Art Edvard Munch Feinblatt, Ebria 1969 Lithographs Etchings 3716 Woodcuts E Art Treasures of early Sweden Gidlunds Statens historiska museumklenoder ur äldre 9281 svensk historia 5964 E Art Another light Granath, Olle 1982 10483 E Art Museum of Far East Antiquities Karlgren, Bernhard, editor in Stockholm 6527 E Art Norwegian Architecture Past and Present Kavli, Guthorm 1958 9468 E Art Joe Hills Sånger Kokk, Enn (redaktør) 1980 10658 E Art Ancient Norwegian Design Museum of National Antiquities,1961 Oslo E Art Norwegian folk art Nelson, Marion, Editor 1995 the migration of a 9822 tradition 9317 E Art Döderhultarn Qvist, Sif 1981? 10181 E Art The Norwegian crown regalia risåsen, Geir Thomas 2006 9823 -

Lindgrens Träd Människors Relation Till Träd I Astrid Lindgrens Sagor

Lindgrens träd Människors relation till träd i Astrid Lindgrens sagor Mimmi Wester Avdelningen för landskapsarkitektur, Examensarbete vid landskapsarkitektprogrammet, 2015 Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Fakulteten för naturresurser och jordbruksvetenskap Institutionen för stad och land, avdelningen för landskapsarkitektur, Uppsala Examensarbete för yrkesexamen på landskapsarkitektprogrammet EX0504 Självständigt arbete i landskapsarkitektur, 30 hp Nivå: Avancerad A2E © 2015 Mimmi Wester, e-post: [email protected] Titel på svenska: Lindgrens träd: människors relation till träd i Astrid Lindgrens sagor Title in English: The trees of Lindgren: the relationship between people and trees in the fairytales of Astrid Lindgren Handledare: Ulla Myhr, institutionen för stad och land Examinator: Ylva Dahlman, institutionen för stad och land Biträdande examinator: Petter Åkerblom, institutionen för stad och land Omslagsbild: Illustration av författaren. Övriga foton och illustrationer: Av författaren om inget annat anges. Samtliga bilder/foton/ illustrationer/kartor i examensarbetet publiceras med tillstånd från upphovsman. Originalformat: A4 Nyckelord: Astrid Lindgren, Litteraturanalys, Skönlitteratur och landskapsarkitektur Träd i skönlitteratur, Upplevelse av träd Online publication of this work: http://epsilon.slu.se Förord Redan som barn hade jag en stor kärlek för alla sorters växter, vilket så småningom förde mig till landskapsarkitektprogrammet i vuxen ålder. Jag tror att en stor del av mitt stora växtintresse började med sagorna, rimmen och sångerna som min mamma läste för mig om kvällarna. Genom böckerna fick jag mer kunskap men också bränsle till min fantasi, träden utanför dörren kunde bli något mer än bara träd. När jag sedan skulle välja ett ämne för mitt examensarbete beslöt jag mig för att åter träda in i sagornas värld och undersöka trädens betydelse för stämningen och människorna i Astrid Lindgrens böcker.