The Need for Global Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heidi, by Johanna Spyri

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Heidi, by Johanna Spyri This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Heidi (Gift Edition) Author: Johanna Spyri Commentator: Charles Wharton Stork Illustrator: Maria Kirk Translator: Elisabeth Stork Release Date: March 9, 2007 [EBook #20781] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HEIDI *** Produced by Jason Isbell, Emma Morgan Isbell, Jeannie Howse and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. This file is gratefully uploaded to the PG collection in honor of Distributed Proofreaders having posted over 10,000 ebooks. Transcriber's Note: In the original gift edition, there are 8 margin images repeated on each page, these have been preserved and reproduced at the beginning of each chapter. Inconsistent hyphenation in the original document has been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected in this text. For a complete list, please see the end of this document. HEIDI GIFT EDITION WAVING HER HAND AND LOOKING AFTER HER DEPARTING FRIEND TILL HE SEEMED NO BIGGER THAN A LITTLE DOTToList Page 228 HEIDI BY JOHANNA SPYRI TRANSLATED BY ELISABETH P. STORK WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY CHARLES WHARTON STORK, A.M., PH.D. 14 ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOR BY MARIA L. KIRK GIFT EDITION PHILADELPHIA AND LONDON J.B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY 1919 COPYRIGHT, 1915. BY J.B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY ADDITIONAL ILLUSTRATIONS AND DECORATIONS COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY J.B. -

Penguin Readers Factsheets L E V E L E

Penguin Readers Factsheets l e v e l E T e a c h e r’s n o t e s 1 2 3 Heidi 4 5 by Johanna Spyri 6 ELEMENTARY S U M M A R Y ight-year-old Heidi lives in a village in Switzerland. Johanna Spyri wrote in German but Heidi has been E When both her parents die, she is left in the care of her translated into many languages. A cartoon film was made in aunt Dete. Then Dete moves to Frankfurt to work and Hollywood in 1982. In addition to Heidi, her books include The Heidi must live with her bad-tempered Grandfather high up in Little Alpine Musician, Uncle Titus, Gritli, and Veronica. a mountain chalet. But Heidi is a sweet-tempered child and her Grandfather soon comes to love her. Heidi loves living in BACKGROUND AND THEMES the mountains, going up the hill every day with Peter and his goats. Then one day Aunt Dete comes to take Heidi away to Although it was written well over one hundred years ago, Heidi Frankfurt to live with a rich family and be a friend for twelve- remains in the top 100 list of favourite books for children aged year-old, Clara, who is an invalid. Heidi does not want to leave between 10 and 14 in the UK and it is especially popular with Grandfather and the mountains. In Frankfurt, she makes girls. How is it that the story retains its appeal? First, in writing friends with Clara and learns to read, but she does not like Heidi, it is clear that Johanna Spyri drew upon the memories living in the city and thinks all the time of returning home. -

Heidi, Bergère Planétaire Décryptage

LA LIBERTE (SUISSE) 11/12 AOUT 12 Quotidien Etranger 1700 FRIBOURG Surface approx. (cm²) : 690 N° de page : 25 Page 1/2 Heidi, bergère planétaire Décryptage.. La petite fille grisonne, imaginée en 1880 par Johanna Spyri, traverse les ans sans prendre une ride. JOHANNA SPYRI > Née en 1827 a Hirzel dans le can- ton de Zurich Son pere est mede- cin, et sa mere fille de pasteur > Elle fait ses études scolaires a Hirzel et poursuit sa formation a Zurich ou elle apprend les langues modernes et le piano > L'amour des livres marque sa jeu- nesse En découvrant Goethe, entre autres, elle se détache de la vision pieuse du monde transmise par sa mere > Elle passe de nombreux êtes a Jenms et Maienfeld, dans les Gri sons qui deviendront plus tard le decor dè «Heidi» > En 1852 elle épouse Johann BernhardSpyn qui est avocat puis chancelier dè la ville de Zurich Elle lui donne un fils unique, Bernhard, qui décède en 1884 > Après la mort de son fils et de son man, elle se consacre a l'écri- ture et aux œuvres de chante > Elle publie une cinquantaine de livres, dont Heidi Ledition originale paraît en deux tomes en 1880 et 1881 > Johanna Spyri décède en 1901, a Zurich > En 2001. pour le 100eanniversaire de sa mort, la Confederation lui de die une piece de monnaie comme- morative GA/SWISSINFOCH Décidément, Heidi nous rend tous «timbrés»... Il y a deux ans, La Poste a mandaté la graphiste Karin Widmer pour créer un timbre à l'effigie de la petite bergère. -

Hello, Dear Enemy! Picture Books for Peace and Tolerance: an International Selection

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 460 339 CS 013 281 AUTHOR Scharioth, Barbara, Ed.; Weber, Jochen, Ed. TITLE Hello, Dear Enemy! Picture Books for Peace and Tolerance: An International Selection. INSTITUTION International Youth Library, Munich (Germany). PUB DATE 1998-03-00 NOTE 36p.; In cooperation with International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). Supported by the German Federal Ministry for Family, Senior Citizens, Women, and Youth, the Bavarian Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, and Arts, the City of Munich, and'the Association of the Friends of the International Youth Library. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; Foreign Countries; Global Approach; *Peace; *Picture Books; *Reading Material Selection; Stranger Reactions; Violence; *War; World Problems IDENTIFIERS Peace Education; *Tolerance ABSTRACT This catalog presents descriptions of over 41 children's picture books from 19 countries that formed an exhibition sent worldwide to promote and help maintain peace. The majority of the books do not deal directly with the horrors of war but rather deal with its preconditions: intolerance, xenophobia, prejudice against being different, misuse of power, oppression, and violence against people and property. Titles are arranged alphabetically by illustrator and the books are listed under their country of origin. (Contains author and illustrator name and subject indexes.) (RS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. !he 11c9 dear enemy! Picture Books for Peace nd 'Mem c PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS A erratkm al Selection BEEN GRANTED BY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCAIION Office o4 Educational Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) (1104document has been reproduced as TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES received from the person or organization INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) originating it. -

Heididorf Brochure in Englisch.Pdf

english Best wishes from Heididorf Maienfeld the original Maienfeld . Graubünden . Switzerland Experience Heidi as a wonderfully likable world star at the original location at the authentic Heididorf HEIDI A WORLD STAR AT THE ORIGINAL LOCATION MAIENFELD For decades Heidi has inspired and exci- ted children from around the world and made the hearts of adults beat faster as well. Despite international appearances in musicals, anima- ted series, fi lms and books, our Heidi never forgot her roots. Nowhere else in the world is Heidi’s spirit and personality more evident than in the authentic Heididorf with Heidi’s original house, Heidi’s Alp hut, animals, museums, etc. Pure nature – Heidi’s Alp hut Heidi’s Home, Maienfeld Heidi’s house Johanna Spyri’s Heidiwelt Museum - original props and costumes from the 2015 HEIDI fi lm - biography of Johanna Spyri - all Heidi fi lms More information at..... .....www.heididorf.ch The clock is turned back to the time around 1880, when Heidi and her grandmother and all of the known people lived in a village commu- nity. The hard winters at that time presented a great challenge for these self-suffi cient people. Heidi’s house in the little village Heididorf is emotional time travel back to Animal adventures the Swiss mountain world of the late 19th cen- tury. Heidi’s and Peter’s pets greet the visitors in front of the house. A guided tour, when re- quested, shows a very authentic original Heidi world: From the cellar used to store food, you continue up to the rustic parlour, where Heidi and Geissenpeter await you. -

A Comprehensive Review of Dissertations from 2010 to 2019

A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF DISSERTATIONS FROM 2010 TO 2019 INSTRUCTIONAL PRACTICES AND PREPARATION FOR PRE-SERVICE TEACHERS IN USING MULTICULTURAL AND INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S AND YOUNG ADULT’S LITERATURE: A COMPREHENSIVE SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW ___________ A Dissertation Presented to The faculty of The College of Education Sam Houston State University ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education ___________ by Ragina Dian Rice Shearer December 2020 A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF DISSERTATIONS FROM 2010 TO 2019 INSTRUCTIONAL PRACTICES AND PREPARATION FOR PRE-SERVICE TEACHERS IN USING MULTICULTURAL AND INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S AND YOUNG ADULT’S LITERATURE: A COMPREHENSIVE SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW By Ragina Dian Rice Shearer ___________ Approved: Nancy K. Votteler, EdD Committee Director Hannah Gerber PhD Committee Member Melinda Miller, PhD Committee Member Teri Lesesne, EdD Committee Member Stacey L. Edmonson, EdD Dean, College of Education DEDICATION I dedicate this to the outstanding professors who have guided my way through all my doctoral studies, both at Sam Houston State University and at the University of North Texas. I have had many incredible experiences I have engaged in many extraordinary encounters and have been blessed to work with multiple intellectual and knowledgeable professors. I want to thank each one of my children Miranda, Nathan, and Ashley for listening to all my stories over these past few years. These years have been a blessing for me, and I will never forget them. I am thankful for the many of hours of studying together and the late-night runs for fast food. I am thankful to have always known you were supportive and behind me, I could not have done it without your love and support. -

The Definition of Family in Johanna Spyri's Heidi (1880): A

THE DEFINITION OF FAMILY IN JOHANNA SPYRI’S HEIDI (1880): A SOCIOLOGICAL APPROACH RESEARCH PAPER Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of Requirement For Getting Bachelor Degree of Education In English Department by: RINI CHRISTIANA A320060060 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF TEACHING AND TRAINING EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2010 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Family is the main building block of a community, family structure and upbringing determines the social character and personality of any given society. Family is where people all learn: love, caring, compassion, ethics, honesty, fairness, common sense, reason, peaceful conflict resolution and respect for our selves and others, which are the vital fundamental skillsand family values, necessary to live an honorable and prosper life in harmony, in the world community. To have a sense of family values is to have good thoughts, good intentions and good deeds, to love and to care for those whom people are close to and are part of our primary social group, our community, such as children, parents, other family members and friends, and to treat others with the same set of values, the same way people wish to be treated. Family is important because people need a group of loyal supporters. It matters what people think and feel and nobody cares more about us than the members of our families - at least, thathow it should be and it starts from family. The more binding in the family, the better the family will be. When people can count on each other and learn on each other then family works. As the member of family, individual will be taken care and helped by the family. -

Zu Heidis Nachleben Im Film Eigenen Medium Entsprechend Verändern

in: Viceversa. Jahrbuch der Schweizer Literaturen #10(2016) bewegen, sondern vielmehr daran, wie eigenwillig sie den Stoff dem Eigenwillige Echos: Zu Heidis Nachleben im Film eigenen Medium entsprechend verändern. Von Johannes Binotto Eigenwilligkeiten bestimmen denn auch die Heidi-Filme. Dabei ist der In einer frühen Szene aus Luigi Comencinis Heidi-Verfilmung von 1952 unterschiedliche Widerhall des Heidi-Stoffs im Echoraum des Kinos steigen Heidi und der Geißenpeter in die Höhe, um nachzuschauen, umso interessanter, als in den Verfilmungen nicht nur ganz verschie- »wo der Bach herkommt«. Oben auf dem Grat angekommen, zeigt Pe- dene Aspekte von Johanna Spyris Roman hervorgehoben werden, ter seinem Heidi nicht nur die überwältigende Natur, sondern auch, sondern vor allem auch, weil sich Anliegen, Befürchtungen und Ob- wie der eigene Ruf von den sie umgebenden Bergen als Echo wider- sessionen der jeweiligen Zeit und Kultur zeigen, in denen die Verfil- hallt. »Großvater!« und »Heidi!« rufen die Kinder in die Landschaft mungen entstanden sind. Der literarische Stoff wird zur Versuchsan- und das Echo spricht es ihnen nach. Als jedoch der Geißenpeter in ordnung, in der sich unterschiedlich experimentieren lässt. So nutzt Johannes Binotto seinem Übermut auch ein Schimpfwort in die Landschaft brüllt – schon die allererste Verfilmung, der amerikanische Stummfilm Heidi »dummi, blödi Schwiichatz dräckigi« –, bleibt der Widerhall aus, sehr of the Alps von 1920, Regie Frederick A. Thomson, den Stoff vor allem Essay zum Erschrecken der beiden Kinder, die glauben, das Echo erzürnt zu zur Erprobung der eigenen Technik: Das Alpensetting eignet sich bes- haben. Dieser amüsante Einfall findet sich in der Form nicht in der tens, um das frühe, unterdessen in Vergessenheit geratene Zweifar- Vorlage von Johanna Spyri. -

6Th Grade Summer Reading Assignments

Summer Reading Assignment for Grade 6 1. Choose two books from the attached list to read. 2. For each book, make a list of any new vocabulary words (i.e., words for which you do not know the meanings) and their definitions. 3. Write a two-paragraph summary of each book including the information below: Paragraph 1: characters, setting, plot Paragraph 2: the conflict or problem and its resolution BCA 6th Grade Summer Reading List The Door in the Wall, Marguerite DeAngeli Robin’s plans to become a knight are foiled when he is permanently crippled, but his chance comes as he seeks new ways of service. Misty of Chincoteague, Marguerite Henry Each year ponies from the island of Chincoteague in the Chesapeake Bay are sold for children’s use. This is the story of one of these wild freedom-loving ponies. *Other books by Marguerite Henry are also acceptable. Heidi, Johanna Spyri This is a famous story of a Swiss girl and her experiences in the Swiss Alps. The Trumpet of the Swans, E.B. White Louis is a trumpeter swan who is born without a voice. His father helps him out By getting him a trumpet which he uses as he travels about as a professional musician. The Incredible Journey, Sheila Burnford The original adventure story of two dogs and a cat who are separated from their owners. The Bronze Bow, Elizabeth George Speare Daniel joins an outlaw band to seek revenge for the murder of his parents by the Romans. He meets someone who changes his life. -

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May. American. Born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, 29 November 1832; daughter of the philosopher Amos Bronson Alcott. Educated at home, with instruction from Thoreau, Emerson, and Theodore Parker. Teacher; army nurse during the Civil War; seamstress; domestic servant. Edited the children's magazine Merry's Museum in the 1860's. Died 6 March 1888. PUBLICATIONS FOR CHILDREN Fiction Flower Fables. Boston, Briggs, 1855. The Rose Family: A Fairy Tale. Boston, Redpath, 1864. Morning-Glories and Other Stories, illustrated by Elizabeth Greene. New York, Carleton, 1867. Three Proverb Stories. Boston. Loring, 1868. Kitty's Class Day. Boston, Loring, 1868. Aunt Kipp. Boston, Loring, 1868. Psyche's Art. Boston, Loring, 1868. Little Women; or, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy, illustrated by Mary Alcott. Boston. Roberts. 2 vols., 1868-69; as Little Women and Good Wives, London, Sampson Low, 2 vols .. 1871. An Old-Fashioned Girl. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low, 1870. Will's Wonder Book. Boston, Fuller, 1870. Little Men: Life at Pluff?field with Jo 's Boys. Boston, Roberts, and London. Sampson Low, 1871. Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag: My Boys, Shawl-Straps, Cupid and Chow-Chow, My Girls, Jimmy's Cruise in the Pinafore, An Old-Fashioned Thanksgiving. Boston. Roberts. and London, Sampson Low, 6 vols., 1872-82. Eight Cousins; or, The Aunt-Hill. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low. 1875. Rose in Bloom: A Sequel to "Eight Cousins." Boston, Roberts, 1876. Under the Lilacs. London, Sampson Low, 1877; Boston, Roberts, 1878. Meadow Blossoms. New York, Crowell, 1879. Water Cresses. New York, Crowell, 1879. Jack and Jill: A Village Story. -

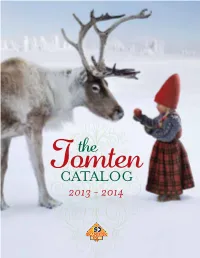

Tomten Catalog Is Produced by Skandisk, Inc

the TomtenCATALOG 2013 - 2014 CHRISTMAS BOOKS FOR ALL AGES Christmas Cards Notecards page 6 page 32 Little Tomte’s Christmas Wish Santa Claus and the Three Bears by Inkeri Karvonen Illustrated by Hannu Taina by Maria Modugno Illustrated by Jane & Brook Dyer The Christmas Wish by Lori Evert & Per Breiehagen Little Tomte embarks on a candle-making plan When Papa Bear, Mama Bear, and Baby Bear return from “The tale follows Anja as she ventures through ice and snow on skis, aided to help his Christmas wish come true. Children a snowy stroll on Christmas Eve, they are surprised at what by several animals, to find Santa Claus.”—Publishers Weekly will enjoy this heartwarming festive tale from they find. This book positively glows with warmth and humor. Hardcover. $17.99 CHR 600 Finland. Ages 4-10. Hardcover. Hardcover. $17.99 CHR 604 $17.95 CHR 603 Snow Bunny’s Christmas Wish The Tomtes’ Christmas Porridge The Christmas Angels The Sparkle Box by Jill Hardie by Rebecca Harry by Sven Nordqvist by Else Wenz Viëtor The moving story of an uncommon gift and The only present Snow Bunny truly wants When the family forgets to leave porridge for On Christmas Eve the Christmas angels fly how giving to others shows a little boy the for Christmas is a friend. Can Santa make the tomtes on Christmas Eve, Mama tomte down to help those in need. First published in true meaning of Christmas. Includes a glitter- her wish come true? Dazzling foil effects hatches a plan before Papa tomte finds out! Germany in 1933, this beautiful book features coated fold-out Sparkle Box! Ages 4-8. -

Ideological Transactions: a Case Study of Elementary School

IDEOLOGICAL TRANSACTIONS: A CASE STUDY OF ELEMENTARY SCHOOL TEACHERS’ DIALOGS WITH INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S PICTUREBOOKS by OKSANA LUSHCHEVSKA (Under the Direction of Jennifer M. Graff) ABSTRACT Literacy scholars assert that an introduction to diversity and global perspective using literature is most effective at the elementary level (Lehman, Freeman, & Scharer, 2010; Schultz; 2010; Stan, 1999) and well-trained teachers can teach multicultural literature and international literature to all students with the same success and expectations despite their own different background/race/gender (Schultz, 2010, p. 18). However, a number of factors influence K-12 educators’ selection of children’s books for classroom use (Serafini, 2013). This study focuses primarily on what happens when in-service elementary school teachers transact with selected international children’s picturebooks. By focusing on how and why teachers vacillate between aesthetic reception and resistance (Rosenblatt, 1978; Soter, 1997) when reading international children’s literature, we can better understand ways by which we can match readers (teachers and students) with international children’s literature. Additionally, we can better understand the ideological underpinnings of elementary school teachers’ transactions with the selected international children’s picturebooks. INDEX WORDS: international children’s literature, elementary school teachers, transactional theory, heteroglossia IDEOLOGICAL TRANSACTIONS: A CASE STUDY OF ELEMENTARY SCHOOL TEACHERS’ DIALOOGS WITH INTERNATIONAL