Megan Doherty Dissertation Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

A Guide to Defending Writers Under Attack

A guide to defending writers under attack The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN ‘I have personally known writers who have chosen to raise forbidden topics purely because they were forbidden. I think I am no different. Because when another writer in another house is not free, no writer is free. This, indeed, is the spirit that informs the solidarity felt by International PEN, by writers all over the world’ Orhan Pamuk A guide to defending writers under attack: The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN Contents Introduction 3 Part One: What is International PEN? 6 International PEN Charter 7 Part Two: An introduction to the Writers in Prison Committee 8 How does the Writers in Prison Committee work? 9 Part Three: Joining the Writers in Prison Committee 12 Part Four: Who does the Writers in Prison Committee work for? 14 Case List 15 Part Five: The Writers in Prison Committee Activities & Resources 17 Honorary Members 17 Rapid Action Network 23 Writing Offi cial Appeals 27 Biennial Conferences 32 Campaign and Focus Actions 32 The Day of the Imprisoned Writer & other international days 34 Meetings with Ambassadors and Governments 36 Embassy Visits 37 Visits to your foreign ministry 37 Trial observations and other missions 38 Working with other NGOs 38 Approaching Intergovernmental organisations 38 Working with Writers in Exile 39 PEN Emergency Fund 39 Awards 40 Part Six: Media and Publicity: raising public awareness and infl uencing opinion 40 Part Seven: The Writers in Prison Committee and International PEN 44 Part Eight: Resources and Glossary 47 2 A guide to defending writers under attack: The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN September 2010 Dear colleagues in International PEN, It is a great pleasure to be able to present to you, at the 76th Congress of International PEN in Tokyo, printed copies of the Writers in Prison Committee’s handbook, A guide to defending writers under attack. -

World War 11

World War 11 When the British Government declared war against Germany in September 1939, notices went out to many people requiring them to report to recruiting centres for assessment of their fitness to serve in the armed forces. Many deaf men went; and many were rejected and received their discharge papers. Two discharge certificates are shown, both issued to Herbert Colville of Hove, Sussex. ! man #tat I AND NATIOIUL WVlc4 m- N.S. n. With many men called up, Britain was soon in dire need of workers not only to contribute towards the war but to replace men called up by the armed forces. Many willing and able hands were found in the form of Deaf workers. While many workers continued in their employment during the war, there were many others who were requisitioned under Essential Works Orders (EWO) and instructed to report to factories elsewhere to cany out work essential to the war. Deaf females had to do ammunition work, as well as welding and heavy riveting work in armoury divisions along with males. Deaf women were generally so impressive in their war work that they were in much demand. Some Deaf ladies were called to the Land Army. Carpenters were also in great demand and they were posted all over Britain, in particular in naval yards where new ships were being fitted out and existing ships altered for the war. Deaf tailors and seamstresses were kept busy making not only uniforms and clothing materials essential for the war, but utility clothes that were cheaply bought during the war. -

Memories Come Flooding Back for Ogs School’S Last Link with Headingley

The magazine for LGS, LGHS and GSAL alumni issue 08 autumn 2020 Memories come flooding back for OGs School’s last link with Headingley The ones to watch What we did Check out the careers of Seun, in lockdown Laura and Josh Heart warming stories in difficult times GSAL Leeds United named celebrates school of promotion the decade Alumni supporters share the excitement 1 24 News GSAL launches Women in Leadership 4 Memories come flooding back for OGs 25 A look back at Rose Court marking the end of school’s last link with Headingley Amraj pops the question 8 12 16 Amraj goes back to school What we did in No pool required Leeds United to pop the question Lockdown... for diver Yona celebrates Alicia welcomes babies Yona keeping his Olympic promotion into a changing world dream alive Alumni supporters share the excitement Welcome to Memento What a year! I am not sure that any were humbled to read about alumnus John Ford’s memory and generosity. 2020 vision I might have had could Dr David Mazza, who spent 16 weeks But at the end of 2020, this edition have prepared me for the last few as a lone GP on an Orkney island also comes at a point when we have extraordinary months. Throughout throughout lockdown, and midwife something wonderful to celebrate, the toughest school times that Alicia Walker, who talks about the too - and I don’t just mean Leeds I can recall, this community has changes to maternity care during 27 been a source of encouragement lockdown. -

ICLA 2016 – Abstracts General Conference Sessions, July 17Th, 2016

ICLA 2016 – Abstracts General Conference Sessions, July 17th, 2016 ICLA 2016 – Abstracts General Conference Sessions Content Fri, July 22nd, 09:00, Urmil Talwar , C. Many cultures, many idioms ..................................................... 7 Fri, July 22nd, 11:00, Marjanne Gooze, D. The language of thematics ................................................... 8 Fri, July 22nd, 11:00, Marta Teixeira Anacleto, D. The language of thematics ....................................... 9 Fri, July 22nd, 18:00, no chair yet, E. Comparatists at work - professional communication ................ 11 Fri, Huly 22nd, 16:00, no chair yet, C. Many cultures, many idioms ..................................................... 11 Fri, July 22nd, 11:00, no chair yet, D. The language of thematics ......................................................... 12 Fri, July 22nd, 14:00, no chair yet, D. The language of thematics ......................................................... 13 Fri, July 22nd, 09:00, no chair yet , C. Many cultures, many idioms ..................................................... 14 Fri, July 22nd, 11:00, Yiu-wai Chu , C. Many cultures, many idioms ..................................................... 15 Fri, July 22nd, 14:00, Gabriele Eckart, C. Many cultures, many idioms ................................................ 17 Fri, July 22nd, 16:00, Nagla Bedeir, E. Comparatists at work - professional communication ............... 18 Fri, July 22nd, 09:00, no chair yet, D. The language of thematics ........................................................ -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1. -

The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941 Colin Cook University of Central Florida Part of the European History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cook, Colin, "Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6734. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6734 BUILDING UNITY THROUGH STATE NARRATIVES: THE EVOLVING BRITISH MEDIA DISCOURSE DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939-1941 by COLIN COOK J.D. University of Florida, 2012 B.A. University of North Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2019 ABSTRACT The British media discourse evolved during the first two years of World War II, as state narratives and censorship began taking a more prominent role. I trace this shift through an examination of newspapers from three British regions during this period, including London, the Southwest, and the North. My research demonstrates that at the start of the war, the press featured early unity in support of the British war effort, with some regional variation. -

Rocznik 2019

ISSN 1898-1127 GDAŃSKI ROCZNIK EWANGELICKI vol. XIII Gdańsk 2019 Parafia Ewangelicko-Augsburska w Gdańsku z siedzibą w Sopocie 1 RADA NAUKOWA Heinrich Assel – Uniwersytet w Greifswaldzie, RFN, Piotr Birecki – UMK, Jerzy Domasłowski – UAM, bp Marcin Hintz – ChAT, Jan Iluk – UG, Jarosław Kłaczkow – UMK, Paweł A. Leszczyński – Akademia im. Jakuba z Paradyża, Bogumił B.J. Linde – UG, Janusz Małłek – UMK, Magdalena I. Sacha – UG, Tadeusz Stegner – UG, Józef Szymeczek – Uniwersytet Ostrawski, Czechy REDAKCJA bp Marcin Hintz – redaktor naczelny, Joanna Arszyńska – sekretarz, Marta Borzych, Maria Drapella, Astrid Gotowt, Iwona Hintz, Maria Urbańska-Bożek, Krzysztof Maria Różański Redaktor działu Historia – Tadeusz Stegner Redaktor języka angielskiego – Bolesław Borzycki RECENZENCI STALI ks. dr hab. Grzegorz Szamocki, prof. UG; prof. dr hab. Grzegorz M. Jasiński; prof. dr hab. Hans-Martin Barth; dr hab. Sławomir Kościelak, prof. UG RECENZENCI BIEśĄCEGO NUMERU dr Michał Białkowski, ks. prof. dr hab. Jacek Bramorski, ks. prof. dr hab. Zygfryd Glaeser, dr hab. Maria Gołębiewska, dr hab. Małgorzata Grzywacz, ks. prof. dr hab. Przemysław Kantyka, prof. dr hab. Jarosław Kita, prof. dr hab. Jarosław Kłaczkow, dr hab. Piotr Kopiec, dr hab. Paweł Leszczyński, dr hab. Józef Majewski, prof. dr hab. Janusz Małłek, prof. dr hab. Zbigniew Opacki, dr hab. Anna Paner, ks. dr hab. Sławomir Pawłowski, dr Miłosz Puczydłowski, prof. dr hab. Jarosław Płuciennik, dr hab. Jacek A. Prokopski, dr hab. Ewa Skrodzka, dr hab. Jan Szturc, dr hab. Damian Wąsek WYDAWCA Parafia Ewangelicko-Augsburska, 81-703 Sopot, ul. Kościuszki 51, tel. 58 551 13 35, e-mail: [email protected]; www.gre.luteranie.pl SKŁAD Przemysław Jodłowski PROJEKT OKŁADKI Jerzy Kamrowski RóŜa Lutra: detal z witraŜa kościoła Zbawiciela w Sopocie, fot. -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

Eli Whalley's Donkey Stones

71 June 2013 Issue THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SOCIAL HISTORY CURATORS GROUP Experimental Re-interpretation & Display Community Engagement at Birmingham Eli Whalley’s Donkey Stones Medical Objects Part II Join SHCG? If you’re reading this and you’re Welcome to Issue 71 not a member of SHCG but would like to join please contact: At the end of June Laura Briggs a new permanent Membership Secretary exhibition opens at Email: [email protected] Newcastle’s Theatre Royal, in which the history of Write an article for theatre is charted SHCG News? from its origins in You can write an article for the News Ancient Greece to on any subject that you feel would be the present day. An interesting to the museum community. important part of Project write ups, book reviews, object the narrative studies, papers given and so on. We focuses on the welcome a wide variety of articles medieval mystery Model of Noah's ark relating to social history and museums. plays, in which Image courtesy of Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: stories from the 18 October 2013 Bible were acted out. Among the best known of the mystery plays was the story of Noah and SHCG NEWS will encourage the Flood. To help illustrate this in the Theatre Royal exhibition a model ark and publish a wide range of views from was sought, and Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums were happy to help as those connected with history and we have, would you believe, not one but two models of Noah’s handiwork. museums. -

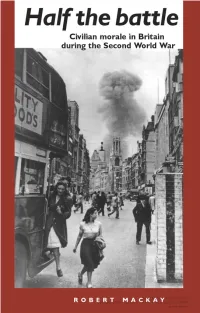

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs.