Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Modern Development on London's Doorstep

1 1 A modern development on London’s doorstep. 2 3 2 3 4 4 4 5 Fusing cosmopolitan connections with relaxed living The Gate House, an exclusive With direct links to central development brought to you by London and less than 3 miles from Telereal Trillium, offers 6 beautiful homes and 31 spacious apartments, Heathrow Airport, The Gate House located in the bustling town of offers an attractive location for Ashford. commuters and jet-setters alike. Aside from having the delights of London on your doorstep, Ashford itself provides the perfect suburban retreat - thriving with cafés, eateries, parks and nearby river walks. And, when you’re not enjoying everything this diverse area has to offer, why not just sit back, relax and enjoy the comfort and privacy of your contemporary new home? 6 7 7 7 Your gateway to the Capital Whether you’re commuting to the City or travelling abroad, a home at The Gate House is very well connected. Ashford mainline station is just a 6 minute drive away with direct links to Waterloo. While Heathrow and the M25 can be reached in just 10 minutes by car. BY TRAIN Ashford BY CAR Twickenham Sunbury-on-Thames 12 minutes 7 minutes Clapham Junction Heathrow 27 minutes 10 minutes London Waterloo Twickenham 38 minutes 15 minutes Reading Kingston 1 hour 20 minutes Windsor 25 minutes 8 8 11 9 M4 M4 M4 Windsor Kew Heathrow Airport Hounslow Legoland® M25 Richmond Feltham Twickenham Ashford Egham Staines-upon-Thames A3 Sunbury-on-Thames M25 Kingston upon Thames Thorpe Park Ascot M3 Virginia Water Hampton Court Palace M3 Wentworth Sunningdale Shepperton Chertsey Walton-on-Thames M3 A3 M25 Weybridge Esher Towns Attractions International connections, right on your doorstep As well as its easy links to central London, The Gate House is only a 10 minute drive away from the employment hubs of Heathrow Airport and Staines-upon-Thames. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas a Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill As a Liberal J

Journal of Issue 25 / Winter 1999–2000 / £5.00 Liberal DemocratHISTORY Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas A Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill as a Liberal J. Graham Jones A Breach in the Family Megan and Gwilym Lloyd George Nick Cott The Case of the Liberal Nationals A re-evaluation Robert Maclennan MP Breaking the Mould? The SDP Liberal Democrat History Group Issue 25: Winter 1999–2000 Journal of Liberal Democrat History Political Defections Special issue: Political Defections The Journal of Liberal Democrat History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group 3 Crossing the floor ISSN 1463-6557 Graham Lippiatt Liberal Democrat History Group Editorial The Liberal Democrat History Group promotes the discussion and research of 5 Out from under the umbrella historical topics, particularly those relating to the histories of the Liberal Democrats, Liberal Tony Little Party and the SDP. The Group organises The defection of the Liberal Unionists discussion meetings and publishes the Journal and other occasional publications. 15 Winston Churchill as a Liberal For more information, including details of publications, back issues of the Journal, tape Senator Jerry S. Grafstein records of meetings and archive and other Churchill’s career in the Liberal Party research sources, see our web site: www.dbrack.dircon.co.uk/ldhg. 18 A failure of leadership Hon President: Earl Russell. Chair: Graham Lippiatt. Roy Douglas Liberal defections 1918–29 Editorial/Correspondence Contributions to the Journal – letters, 24 Tory cuckoos in the Liberal nest? articles, and book reviews – are invited. The Journal is a refereed publication; all articles Nick Cott submitted will be reviewed. -

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 Min)

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 min) Directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard Written by George Bernard Shaw (play, scenario & dialogue), W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple (uncredited), Anatole de Grunwald (uncredited), Kay Walsh (uncredited) Produced by Gabriel Pascal Original Music by Arthur Honegger Cinematography by Harry Stradling Edited by David Lean Art Direction by John Bryan Costume Design by Ladislaw Czettel (as Professor L. Czettel), Schiaparelli (uncredited), Worth (uncredited) Music composed by William Axt Music conducted by Louis Levy Leslie Howard...Professor Henry Higgins Wendy Hiller...Eliza Doolittle Wilfrid Lawson...Alfred Doolittle Marie Lohr...Mrs. Higgins Scott Sunderland...Colonel George Pickering GEORGE BERNARD SHAW [from Wikipedia](26 July 1856 – 2 Jean Cadell...Mrs. Pearce November 1950) was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the David Tree...Freddy Eynsford-Hill London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing Everley Gregg...Mrs. Eynsford-Hill was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many Leueen MacGrath...Clara Eynsford Hill highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for Esme Percy...Count Aristid Karpathy drama, and he wrote more than 60 plays. Nearly all his writings address prevailing social problems, but have a vein of comedy Academy Award – 1939 – Best Screenplay which makes their stark themes more palatable. Shaw examined George Bernard Shaw, W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple education, marriage, religion, government, health care, and class privilege. ANTHONY ASQUITH (November 9, 1902, London, England, UK – He was most angered by what he perceived as the February 20, 1968, Marylebone, London, England, UK) directed 43 exploitation of the working class. -

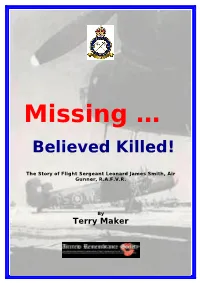

Missing … Believed Killed!

Missing … Believed Killed! The Story of Flight Sergeant Leonard James Smith, Air Gunner, R.A.F.V.R. By Terry Maker Missing - Believed Killed Terry Maker is a retired computer engineer, who has taken to amateur genealogy, after retirement due to ill health in 2003. He is the husband of Patricia Maker, nee Gash, and brother in law of Teddy Gash, (the cousins of Fl/Sgt L.J. Smith). He served as a Civilian Instructor in the Air Training Corps, at Stanford le Hope from 1988 until 1993.The couple live in Essex, and have done so for 36 years; they have no children, and have two golden retrievers. Disclaimer The contents of this document are subject to constant, and unannounced, revision. All of the foregoing is ‘as found’, and assumed to be correct at the time of compilation, and writing. However, this research is ongoing, and the content may be subject to change in the light of new disclosure and discovery, as new information comes to light. We ask for your indulgence, and understanding, in this difficult, and delicate area of research. There is copyright, on, and limited to, new material generated by the author, all content not by the author is, ‘as found’, in the Public Domain. © Terry Maker, 2009 Essex. Front Cover Watermark: “JP292-W undergoing routine maintenance at Brindisi, 1944” (Please note: This photograph is of unknown provenance, and is very similar to the “B-Beer, Brindisi, 1943” photo shown elsewhere in this booklet. It may be digitally altered, and could be suspect!) 2 A story of World War II Missing… Believed Killed By Terry Maker 3 To the men, living and dead, who did these things?” Paul Brickhill 4 Dedicated to the Memory of (Enhanced photograph) Flight Sergeant Leonard James Smith, Air Gunner, R.A.F.V.R. -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

UK TV Outside Broadcast Fibre Connected Venues

UK TV Outside Broadcast fibre connected venues From UK venues to a North of England Arenas Middlesbrough FC Blackpool Winter Gardens Newcastle United FC worldwide audience Sheffield United FC Echo Arena Liverpool Manchester Arena Wigan Athletic FC Football and training Horse racing grounds Aintree Racecourse Barnfield (Burnley FC) Beverley Racecourse Burnley FC Carlisle Racecourse Carrington Complex Cartmel Racecourse (Man Utd FC) Catterick Racecourse Darsley Park (Newcastle FC) Chester Racecourse Etihad Complex (Man City FC) Haydock Racecourse Scotland Everton FC Market Rasen Racecourse Arenas St Johnstone FC Finch Farm (Everton FC) Pontefract Racecourse Hallam FM Academy Redcar Racecourse SEC Centre St Mirren FC (Sheff Utd FC) Thirsk Racecourse Football and Horse racing Leeds United FC Wetherby Racecourse training grounds Ayr Racecourse Leigh Sports Village York Racecourse Aberdeen FC Hamilton Racecourse Liverpool FC Celtic FC Kelso Racecourse Manchester City FC Rugby AJ Bell Stadium Dundee United FC Musselburgh Manchester United FC Leigh Sports Village Hamilton Academical Racecourse Melwood Training Ground FC Perth Racecourse (Liverpool FC) Newcastle Falcons Hibernian FC Rugby Kilmarnock FC Scotstoun Stadium Livingstone FC Motherwell FC Stadiums Rangers FC Hampden Stadium Ross County FC Murrayfield Stadium Midlands and East of England Arenas West Bromwich Albion FC Birmingham NEC Wolverhampton Coventry Ricoh Arena Wanderers FC Wales and Wolverhampton Civic Hall Horse racing Football and Cheltenham Racecourse training grounds Gloucester -

Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil.Pdf

Leo Strauss Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil A course offered in 1971–1972 St. John’s College, Annapolis, Maryland Edited and with an introduction by Mark Blitz With the assistance of Jay Michael Hoffpauir and Gayle McKeen With the generous support of Douglas Mayer Mark Blitz is Fletcher Jones Professor of Political Philosophy at Claremont McKenna College. He is author of several books on political philosophy, including Heidegger’s Being and Time and the Possibility of Political Philosophy (Cornell University Press, 1981) and Plato’s Political Philosophy (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), and many articles, including “Nietzsche and Political Science: The Problem of Politics,” “Heidegger’s Nietzsche (Part I),” “Heidegger’s Nietzsche (Part II),” “Strauss’s Laws, Government Practice and the School of Strauss,” and “Leo Strauss’s Understanding of Modernity.” © 1976 Estate of Leo Strauss © 2014 Estate of Leo Strauss. All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Editor’s Introduction i–viii Note on the Leo Strauss Transcript Project ix–xi Editorial Headnote xi–xii Session 1: Introduction (Use and Abuse of History; Zarathustra) 1–19 Session 2: Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorisms 1–9 20–39 Session 3: BGE, Aphorisms 10–16 40–56 Session 4: BGE, Aphorisms 17–23 57–75 Session 5: BGE, Aphorisms 24–30 76–94 Session 6: BGE, Aphorisms 31–35 95–114 Session 7: BGE, Aphorisms 36–40 115–134 Session 8: BGE, Aphorisms 41–50 135–152 Session 9: BGE, Aphorisms 51–55 153–164 Session 10: BGE, Aphorisms 56–76 (and selections) 165–185 Session 11: BGE, Aphorisms 186–190 186–192 Session 12: BGE, Aphorisms 204–213 193–209 Session 13 (unrecorded) 210 Session 14: BGE, Aphorism 230; Zarathustra 211–222 Nietzsche, 1971–72 i Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil Mark Blitz Leo Strauss offered this seminar on Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil at St John’s College in Annapolis Maryland. -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence

Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Jon Woronoff, Series Editor 1. British Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2005. 2. United States Intelligence, by Michael A. Turner, 2006. 3. Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. 4. International Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2006. 5. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. 6. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. 7. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. 8. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. 9. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 9 The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trenear-Harvey, Glenmore S., 1940– Historical dictionary of air intelligence / Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey. p. cm. — (Historical dictionaries of intelligence and counterintelligence ; no. 9) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5982-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8108-5982-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-6294-4 (eBook) ISBN-10: 0-8108-6294-8 (eBook) 1. -

Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945 Jordan I

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-7-2018 Britain Can Take It: Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945 Jordan I. Malfoy [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006585 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Malfoy, Jordan I., "Britain Can Take It: Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3639. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3639 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida BRITAIN CAN TAKE IT: CHEMICAL WARFARE AND THE ORIGINS OF CIVIL DEFENSE IN GREAT BRITAIN, 1915 - 1945 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Jordan Malfoy 2018 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. choose the name of dean of your college/school Green School of International and Public Affairs choose the name of your college/school This disserta tion, writte n by Jordan Malfoy, and entitled Britain Can Take It: Chemical Warfare and the Ori gins of Civil D efense i n Great Britain, 1915-1945, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

Nimal Dunuhinga - Poems

Poetry Series nimal dunuhinga - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive nimal dunuhinga(19, April,1951) I was a Seafarer for 15 years, presently wife & myself are residing in the USA and seek a political asylum. I have two daughters, the eldest lives in Austalia and the youngest reside in Massachusettes with her husband and grand son Siluna.I am a free lance of all I must indebted to for opening the gates to this global stage of poets. Finally, I must thank them all, my beloved wife Manel, daughters Tharindu & Thilini, son-in-laws Kelum & Chinthaka, my loving brother Lalith who taught me to read & write and lot of things about the fading the loved ones supply me ingredients to enrich this life's bitter-cake.I am not a scholar, just a sailor, but I learned few things from the last I found Man is not belongs to anybody, any race or to any religion, an independant-nondescript heaviest burden who carries is the Brain. Conclusion, I guess most of my poems, the concepts based on the essence of Buddhist personal belief is the Buddha who was the greatest poet on this planet earth.I always grateful and admire him. My humble regards to all the readers. www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 * I Was Born By The River My scholar friend keeps his late Grandma's diary And a certain page was highlighted in the color of yellow. My old ferryman you never realized that how I deeply loved you? Since in the cradle the word 'depth' I heard several occasions from my parents.