Human Rights in the Twentieth-Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politician Truth Will Ultimately Prevail Where There Is Pains Taken to Bring It to Light

The Politician Truth will ultimately prevail where there is pains taken to bring it to light. —George Washington Obvious pressures to smother and ignore The Politician since its official publication are unmatched in the history of the American book world. Now that this explosive volume is available to anyone who will read and judge for himself, the hundreds of periodicals which were quoting and misquoting from it regularly for two years have failed to give it a review or a mention of any nature. There have been many case histories showing the influence exerted on the seven thousand regular bookstores in the United States which has resulted in a virtual boycott of the book—even by those stores that wanted to offer it for sale. In spite of these problems, the sale of forty thousand copies in the first six months after publication and the continuing strong sale have been encouraging. The truth, so fully documented, is not easy to keep buried, even by all of the powerful influences that are so determined to hide it. BELMONT PUBLISHING COMPANY Belmont, Massachusetts 02178 Copyright 1963 by Robert Welch All rights reserved. Except in quotations for review purposes, of not more than five hundred words in any one review, and then with full credit given, no portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the author. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 64-8456 Manufactured in the United States of America CONTENTS Please Note vi Prologue vii Again, Please Note xvi Dear Reader 1 Introduction 3 1. -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

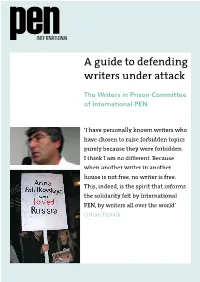

A Guide to Defending Writers Under Attack

A guide to defending writers under attack The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN ‘I have personally known writers who have chosen to raise forbidden topics purely because they were forbidden. I think I am no different. Because when another writer in another house is not free, no writer is free. This, indeed, is the spirit that informs the solidarity felt by International PEN, by writers all over the world’ Orhan Pamuk A guide to defending writers under attack: The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN Contents Introduction 3 Part One: What is International PEN? 6 International PEN Charter 7 Part Two: An introduction to the Writers in Prison Committee 8 How does the Writers in Prison Committee work? 9 Part Three: Joining the Writers in Prison Committee 12 Part Four: Who does the Writers in Prison Committee work for? 14 Case List 15 Part Five: The Writers in Prison Committee Activities & Resources 17 Honorary Members 17 Rapid Action Network 23 Writing Offi cial Appeals 27 Biennial Conferences 32 Campaign and Focus Actions 32 The Day of the Imprisoned Writer & other international days 34 Meetings with Ambassadors and Governments 36 Embassy Visits 37 Visits to your foreign ministry 37 Trial observations and other missions 38 Working with other NGOs 38 Approaching Intergovernmental organisations 38 Working with Writers in Exile 39 PEN Emergency Fund 39 Awards 40 Part Six: Media and Publicity: raising public awareness and infl uencing opinion 40 Part Seven: The Writers in Prison Committee and International PEN 44 Part Eight: Resources and Glossary 47 2 A guide to defending writers under attack: The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN September 2010 Dear colleagues in International PEN, It is a great pleasure to be able to present to you, at the 76th Congress of International PEN in Tokyo, printed copies of the Writers in Prison Committee’s handbook, A guide to defending writers under attack. -

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOSEVELT, THEODORE 1858-1919 Gift of Paul C. Richards, 1976-1990; 1993 Note: Items found in Richards-Roosevelt Room Case are identified as such with the notation ‘[Richards-Roosevelt Room]’. Boxes 1-12 I. Correspondence Correspondence is listed alphabetically but filed chronologically in Boxes 1-11 as noted below. Material filed in Box 12 is noted as such with the notation “(Box 12)”. Box 1 Undated materials and 1881-1893 Box 2 1894-1897 Box 3 1898-1900 Box 4 1901-1903 Box 5 1904-1905 Box 6 1906-1907 Box 7 1908-1909 Box 8 1910 Box 9 1911-1912 Box 10 1913-1915 Box 11 1916-1918 Box 12 TR’s Family’s Personal and Business Correspondence, and letters about TR post- January 6th, 1919 (TR’s death). A. From TR Abbott, Ernest H[amlin] TLS, Feb. 3, 1915 (New York), 1 p. Abbott, Lawrence F[raser] TLS, July 14, 1908 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. ALS, Dec. 2, 1909 (on safari), 4 p. TLS, May 4, 1916 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. TLS, March 15, 1917 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. Abbott, Rev. Dr. Lyman TLS, June 19, 1903 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Nov. 21, 1904 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Feb. 15, 1909 (Washington, D.C.), 2 p. Aberdeen, Lady ALS, Jan. 14, 1918 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. Ackerman, Ernest R. TLS, Nov. 1, 1907 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. Addison, James T[hayer] TLS, Dec. 7, 1915 (Oyster Bay), 1p. Adee, Alvey A[ugustus] TLS, Oct. -

The PEN International Stage & Screen Circle

‘PEN International has traditionally been a place where great artists of stage and screen -Thornton Wilder, Maurice Maeterlinck, Arthur Miller, Ronald Harwood, Octavio Paz and Harold Pinter- have fought for freedom of expression the world over. Today, as even a mobile phone can be a movie camera, we are able to bear witness to human rights violations as never before. In these times, more than ever, PEN defends playwrights, screenwriters and filmmakers who are censored, silenced and jailed’ – JENNIFER CLEMENT, PEN INTERNATIONAL PRESIDENT ‘I consider freedom of expression the most important cause that PEN supports. Without freedom of expression we are lost’ – RONALD HARWOOD, PEN INTERNATIONAL PRESIDENT EMERITUS ‘My respect for this organisation has no borders…PEN has been so fierce, so consistent and ferocious in its efforts that it is hard to ignore their worldwide impact.’ The PEN – TONI MORRISON, PEN INTERNATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT International For more information contact [email protected] Stage & Screen Cover image: PEN International President Emeritus Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe arrive in London for the premier of film The Prince and the Showgirl with Laurence Olivier. Photo by The Print Collector/Getty Images. PEN International is a registered UK charity under the name International P. E. N. Circle Our charity number is 1117088. Who Stage and We Are Screen Circle Although PEN’s membership has always included advocates from the stage and PEN International and the stage and screen worlds have been interwined for almost screen, we are also increasingly fighting for the freedom of playwrights, directors and one hundered years. One of PEN’s founding members, along with H.G Wells, was screenwriters: George Bernard Shaw. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

Pen International Writers in Prison Committee Caselist

PEN INTERNATIONAL WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE CASELIST January-December 2013 PEN International Writers in Prison Committee 50/51 High Holborn London WC1V 6ER United Kingdom Tel: + 44 020 74050338 Fax: + 44 020 74050339 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.pen-international.org PEN INTERNATIONAL CHARTER The P.E.N. Charter is based on resolutions passed at its International Congresses and may be summarised as follows: P.E.N. affirms that: 1. Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals. 2. In all circumstances, and particularly in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large, should be left untouched by national or political passion. 3. Members of P.E.N. should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world. 4. P.E.N. stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong, as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. P.E.N. declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world towards a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. -

Albert Camus and the Anticolonials: Why Camus Would Not Play the Zero Sum Game James D

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2014 Albert Camus and the Anticolonials: Why Camus Would Not Play the Zero Sum Game James D. Le Sueur University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, History Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Le Sueur, James D., "Albert Camus and the Anticolonials: Why Camus Would Not Play the Zero Sum Game" (2014). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 192. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/192 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WHY CAMUS WOULD NOT PLAY THE ZERO SUM GAME / LE SUEUR 27 Albert Camus and the Anticolonials: Why Camus Would Not Play the Zero Sum Game1 James D. Le Sueur, University of Nebraska, Lincoln IN 1994, I RETURNED FROM PARIS TO HYDE PARK just in time to catch a lecture about Albert Camus that an esteemed colleague, the late Tony Judt, was giving at the University of Chicago. I was much younger then, eager to engage in debate, and I had just spent most of the past two years turning over the recently opened pages of Camus’ private papers in Paris and trolling through the private papers of other prominent French intellectuals, as well as newly declassified state archives for what was to become my first book,Uncivil War.2 I had also done dozens of interviews with Camus’ friends and fellow travelers (Jean Daniel, Germaine Tillion, Jean Pélégri, etc.), as well as old adversaries (including Françis Jeanson). -

Politics, Oppression and Violence in Harold Pinter's Plays

Politics, Oppression and Violence in Harold Pinter’s Plays through the Lens of Arabic Plays from Egypt and Syria Hekmat Shammout A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS BY RESEARCH Department of Drama and Theatre Arts College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis aims to examine how far the political plays of Harold Pinter reflect the Arabic political situation, particularly in Syria and Egypt, by comparing them to several plays that have been written in these two countries after 1967. During the research, the comparative study examined the similarities and differences on a theoretical basis, and how each playwright dramatised the topic of political violence and aggression against oppressed individuals. It also focussed on what dramatic techniques have been used in the plays. The thesis also tries to shed light on how Arab theatre practitioners managed to adapt Pinter’s plays to overcome the cultural-specific elements and the foreignness of the text to bring the play closer to the understanding of the targeted audience. -

Freedom Is a Strange Feeling

FREEDOM IS A British Guiana Jagan Wants STRANGE FEELING Independence '^illllllllllllllllliilllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllilllllllllllllllllllillllllllllllllllllllllllltllllllllllllll| By May 31 1 Says HENRI ALLEG, Algerian resistance hero whose book on the tortures to which j I he and others had been subjected first showed the world that the French colonialists were | Dr. Cheddi Jagan, Prime Minister of British Guiana, and' a guest at I using in Algeria the same methods as the Nazis. Alleg recently escaped from a French | the Tanganyikan Independence Celebrations, told a press-conference E jail after five years imprisonment and is now in Czechoslovakia. e in Dar es Salaam that he was meeting Mr. Maudling, the Colonial Secretary, to demand the fixing of ^iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiim Illllllillllllllllllllllllllllllltllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllir his country’s independence date. The main opposition party had asked for independence on May 31, OW that I am free there is come, and when it did we hoped started all over again. 1962, and he was in full agreement. that we would not wake up in the This is why hunger-strikes were N an odd feeling that 1 can morning to sec another of our held so often. A recent one lasted Asked if British Guiana would not shake off. until the Algerian prisoners forced become a member of the Common friends die. wealth, he said that his country was Tt is the strangeness, after years Nor did those sentenced to death the French administration to con Henri Alleg cede to their demands and grant committed to do so, if the Common in prison, of being able to walk sleep. They remained awake so wealth was still there. -

Admirals Disagree Over Naval Pact Before the Senate

<i ^ t THE 'WEATH^E^- Phreeast- by D rS . ......BuptforAr NET PRESS RUN AVERAGE DABLY CIRCULATION; i^uiw uiil oontoraed cold this «fter> fo^ toe Month of A j^ » 1980 noon and ptobably tonight; Finftiyi olondy with slowly rishig tempera 5 , 5 2 7 ture. Uembcra ot the Andlt Bureau of ClrculatloBU ___ Conn. State Library—Ck>mp. SIXTEEN PAGES PRICE THREE CENTS SOUTH MANC;HESTER, c o n n ., THURSDAY, MAY 15, 1930. (Classified ^Advertising on Page 14) VOL. XUV., NO. 193. r EX-CADET CAGLE, AND THE ^ ^ ADMIRALS DISAGREE Leads Revolt in India YALE STUDENTS REASON HE QUIT THE ARMY D R Y BROOK” SUPT. QUESTION IIP ARE SUSPENDED OVER NAVAL PACT TO THE VOTERS F O L L O m R IO T MERIDEN PROBE BEFORE THE SENATE in Statement Say He Did Not Fourteen Come Under Dean’s SOLDIER SAVES LIFE Selectmen Decide Special Merit Discharge for Call OF KING’S SMALL SON HSary P. Jones Says a Kf* Ban; Sixteen Others Lose Town Meeting Should Act Belgrade, Jugo-Slavia, May 15. (erent Setdement Woold ing Attention to Condi __(AP)—Prompt action today of Privileges as Result of a sehtinel outside toe King’s On Sanitary Sewer Dis summer palace saved the life of Have Been Possible; Was tions at the State School. his second son, Tomislav. Disturbances Last We.eh. The sentinel on duty below toe trict Purchase Proposal. nursery ■window saw toe child Naval Adviser at London; New Haven, May. 15.—(AP)— New Haven, May 14.—(AP.)— playing on the balcony, climb to Praise of the investigation precipi toe rail and faU. -

PEN International Impact and Learning Report 2015 to 2019

PEN INTERNATIONAL IMPACT AND LEARNING REPORT 2015 - 2019 On the Frontline Defending Freedom of Expression and Promoting Literature Cover image: During PEN International Congress in Pune, India in 2018, delegates joined local students on a public wari travelling three kilometres over three hours in celebration of global languages. PEN is grateful to its many Overview 1 individual supporters and volunteers who make its 2015 to 2019 work possible including Swedish International 13 Development Cooperation Supporting Agency (Sida), PEN Writers at Risk Publishers, Writers and Readers Circles, International Cities of Refuge Network Challenging 29 (ICORN), the Norwegian Structural Threats Ministry of Foreign Affairs, United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF), Clifford Strengthening 40 Chance, Fritt Ord and Evan Civil Society Cornish Foundation 55 PEN International Looking forward: Unit A - Koops Mill Mews 162-164 Abbey Street London SE1 2AN PEN International United Kingdom PEN International promotes literature and freedom of 2020 to 2023 expression and is governedby the PEN Charter and the principles it embodies: unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations. Founded in 1921, PEN International connects an international community of writers from its Secretariat in London. It is a forum where writers meet freely to discuss their work; it is also a voice speaking out for writers silenced in their own countries. Through Centres in over 100 countries, PEN operates on five continents. PEN International is a non-political organisation which holds Special Consultative Status at the UN and Associate Status at UNESCO. International PEN is a registered charity in England and Wales with registration number 1117088.