Role of the Dysmorphologic Evaluation in the Child with Developmental Delay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pfeiffer Syndrome Type II Discovered Perinatally

Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging (2012) 93, 785—789 CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector LETTER / Musculoskeletal imaging Pfeiffer syndrome type II discovered perinatally: Report of an observation and review of the literature a,∗ a a a H. Ben Hamouda , Y. Tlili , S. Ghanmi , H. Soua , b c b a S. Jerbi , M.M. Souissi , H. Hamza , M.T. Sfar a Unité de néonatologie, service de pédiatrie, CHU Tahar Sfar, 5111 Mahdia, Tunisia b Service de radiologie, CHU Tahar Sfar, 5111 Mahdia, Tunisia c Service de gynéco-obstétrique, CHU Tahar Sfar, 5111 Mahdia, Tunisia Pfeiffer syndrome, described for the first time by Pfeiffer in 1964, is a rare hereditary KEYWORDS condition combining osteochondrodysplasia with craniosynostosis [1]. This syndrome is Pfeiffer syndrome; also called acrocephalosyndactyly type 5, which is divided into three sub-types. Type I Cloverleaf skull; is the classic Pfeiffer syndrome, with autosomal dominant transmission, often associated Craniosynostosis; with normal intelligence. Types II and III occur as sporadic cases in individuals who have Syndactyly; craniosynostosis with broad thumbs, broad big toes, ankylosis of the elbows and visceral Prenatal diagnosis abnormalities [2]. We report a case of Pfeiffer syndrome type II, discovered perinatally, which is distinguished from type III by the skull appearing like a cloverleaf, and we shall discuss the clinical, radiological and evolutive features and the advantage of prenatal diagnosis of this syndrome with a review of the literature. Observation The case involved a male premature baby born at 36 weeks of amenorrhoea with multiple deformities at birth. The parents were not blood-related and in good health who had two other boys and a girl with normal morphology. -

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

Genetics of Congenital Hand Anomalies

G. C. Schwabe1 S. Mundlos2 Genetics of Congenital Hand Anomalies Die Genetik angeborener Handfehlbildungen Original Article Abstract Zusammenfassung Congenital limb malformations exhibit a wide spectrum of phe- Angeborene Handfehlbildungen sind durch ein breites Spektrum notypic manifestations and may occur as an isolated malforma- an phänotypischen Manifestationen gekennzeichnet. Sie treten tion and as part of a syndrome. They are individually rare, but als isolierte Malformation oder als Teil verschiedener Syndrome due to their overall frequency and severity they are of clinical auf. Die einzelnen Formen kongenitaler Handfehlbildungen sind relevance. In recent years, increasing knowledge of the molecu- selten, besitzen aber aufgrund ihrer Häufigkeit insgesamt und lar basis of embryonic development has significantly enhanced der hohen Belastung für Betroffene erhebliche klinische Rele- our understanding of congenital limb malformations. In addi- vanz. Die fortschreitende Erkenntnis über die molekularen Me- tion, genetic studies have revealed the molecular basis of an in- chanismen der Embryonalentwicklung haben in den letzten Jah- creasing number of conditions with primary or secondary limb ren wesentlich dazu beigetragen, die genetischen Ursachen kon- involvement. The molecular findings have led to a regrouping of genitaler Malformationen besser zu verstehen. Der hohe Grad an malformations in genetic terms. However, the establishment of phänotypischer Variabilität kongenitaler Handfehlbildungen er- precise genotype-phenotype correlations for limb malforma- schwert jedoch eine Etablierung präziser Genotyp-Phänotyp- tions is difficult due to the high degree of phenotypic variability. Korrelationen. In diesem Übersichtsartikel präsentieren wir das We present an overview of congenital limb malformations based Spektrum kongenitaler Malformationen, basierend auf einer ent- 85 on an anatomic and genetic concept reflecting recent molecular wicklungsbiologischen, anatomischen und genetischen Klassifi- and developmental insights. -

Macrocephaly Information Sheet 6-13-19

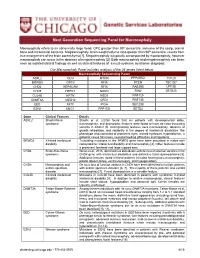

Next Generation Sequencing Panel for Macrocephaly Clinical Features: Macrocephaly refers to an abnormally large head, OFC greater than 98th percentile, inclusive of the scalp, cranial bone and intracranial contents. Megalencephaly, brain weight/volume ratio greater than 98th percentile, results from true enlargement of the brain parenchyma [1]. Megalencephaly is typically accompanied by macrocephaly, however macrocephaly can occur in the absence of megalencephaly [2]. Both macrocephaly and megalencephaly can been seen as isolated clinical findings as well as clinical features of a mutli-systemic syndromic diagnosis. Our Macrocephaly Panel includes analysis of the 36 genes listed below. Macrocephaly Sequencing Panel ASXL2 GLI3 MTOR PPP2R5D TCF20 BRWD3 GPC3 NFIA PTEN TBC1D7 CHD4 HEPACAM NFIX RAB39B UPF3B CHD8 HERC1 NONO RIN2 ZBTB20 CUL4B KPTN NSD1 RNF125 DNMT3A MED12 OFD1 RNF135 EED MITF PIGA SEC23B EZH2 MLC1 PPP1CB SETD2 Gene Clinical Features Details ASXL2 Shashi-Pena Shashi et al. (2016) found that six patients with developmental delay, syndrome macrocephaly, and dysmorphic features were found to have de novo truncating variants in ASXL2 [3]. Distinguishing features were macrocephaly, absence of growth retardation, and variability in the degree of intellectual disabilities The phenotype also consisted of prominent eyes, arched eyebrows, hypertelorism, a glabellar nevus flammeus, neonatal feeding difficulties and hypotonia. BRWD3 X-linked intellectual Truncating mutations in the BRWD3 gene have been described in males with disability nonsyndromic intellectual disability and macrocephaly [4]. Other features include a prominent forehead and large cupped ears. CHD4 Sifrim-Hitz-Weiss Weiss et al., 2016, identified five individuals with de novo missense variants in the syndrome CHD4 gene with intellectual disabilities and distinctive facial dysmorphisms [5]. -

Sotos Syndrome

European Journal of Human Genetics (2007) 15, 264–271 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1018-4813/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/ejhg PRACTICAL GENETICS In association with Sotos syndrome Sotos syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition characterised by a distinctive facial appearance, learning disability and overgrowth resulting in tall stature and macrocephaly. In 2002, Sotos syndrome was shown to be caused by mutations and deletions of NSD1, which encodes a histone methyltransferase implicated in chromatin regulation. More recently, the NSD1 mutational spectrum has been defined, the phenotype of Sotos syndrome clarified and diagnostic and management guidelines developed. Introduction In brief Sotos syndrome was first described in 1964 by Juan Sotos Sotos syndrome is characterised by a distinctive facial and the major diagnostic criteria of a distinctive facial appearance, learning disability and childhood over- appearance, childhood overgrowth and learning disability growth. were established in 1994 by Cole and Hughes.1,2 In 2002, Sotos syndrome is associated with cardiac anomalies, cloning of the breakpoints of a de novo t(5;8)(q35;q24.1) renal anomalies, seizures and/or scoliosis in B25% of translocation in a child with Sotos syndrome led to the cases and a broad variety of additional features occur discovery that Sotos syndrome is caused by haploinsuffi- less frequently. ciency of the Nuclear receptor Set Domain containing NSD1 abnormalities, such as truncating mutations, protein 1 gene, NSD1.3 Subsequently, extensive analyses of missense mutations in functional domains, partial overgrowth cases have shown that intragenic NSD1 muta- gene deletions and 5q35 microdeletions encompass- tions and 5q35 microdeletions encompassing NSD1 cause ing NSD1, are identifiable in the majority (490%) of 490% of Sotos syndrome cases.4–10 In addition, NSD1 Sotos syndrome cases. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0210567 A1 Bevec (43) Pub

US 2010O2.10567A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0210567 A1 Bevec (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 19, 2010 (54) USE OF ATUFTSINASATHERAPEUTIC Publication Classification AGENT (51) Int. Cl. A638/07 (2006.01) (76) Inventor: Dorian Bevec, Germering (DE) C07K 5/103 (2006.01) A6IP35/00 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6IPL/I6 (2006.01) WINSTEAD PC A6IP3L/20 (2006.01) i. 2O1 US (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................... 514/18: 530/330 9 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 12/677,311 The present invention is directed to the use of the peptide compound Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH as a therapeutic agent for (22) PCT Filed: Sep. 9, 2008 the prophylaxis and/or treatment of cancer, autoimmune dis eases, fibrotic diseases, inflammatory diseases, neurodegen (86). PCT No.: PCT/EP2008/007470 erative diseases, infectious diseases, lung diseases, heart and vascular diseases and metabolic diseases. Moreover the S371 (c)(1), present invention relates to pharmaceutical compositions (2), (4) Date: Mar. 10, 2010 preferably inform of a lyophilisate or liquid buffersolution or artificial mother milk formulation or mother milk substitute (30) Foreign Application Priority Data containing the peptide Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH optionally together with at least one pharmaceutically acceptable car Sep. 11, 2007 (EP) .................................. O7017754.8 rier, cryoprotectant, lyoprotectant, excipient and/or diluent. US 2010/0210567 A1 Aug. 19, 2010 USE OF ATUFTSNASATHERAPEUTIC ment of Hepatitis BVirus infection, diseases caused by Hepa AGENT titis B Virus infection, acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, full minant liver failure, liver cirrhosis, cancer associated with Hepatitis B Virus infection. 0001. The present invention is directed to the use of the Cancer, Tumors, Proliferative Diseases, Malignancies and peptide compound Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH (Tuftsin) as a thera their Metastases peutic agent for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of cancer, 0008. -

Identifying the Misshapen Head: Craniosynostosis and Related Disorders Mark S

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care Identifying the Misshapen Head: Craniosynostosis and Related Disorders Mark S. Dias, MD, FAAP, FAANS,a Thomas Samson, MD, FAAP,b Elias B. Rizk, MD, FAAP, FAANS,a Lance S. Governale, MD, FAAP, FAANS,c Joan T. Richtsmeier, PhD,d SECTION ON NEUROLOGIC SURGERY, SECTION ON PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY Pediatric care providers, pediatricians, pediatric subspecialty physicians, and abstract other health care providers should be able to recognize children with abnormal head shapes that occur as a result of both synostotic and aSection of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery and deformational processes. The purpose of this clinical report is to review the bDivision of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, College of characteristic head shape changes, as well as secondary craniofacial Medicine and dDepartment of Anthropology, College of the Liberal Arts characteristics, that occur in the setting of the various primary and Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania; and cLillian S. Wells Department of craniosynostoses and deformations. As an introduction, the physiology and Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, genetics of skull growth as well as the pathophysiology underlying Florida craniosynostosis are reviewed. This is followed by a description of each type of Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from primary craniosynostosis (metopic, unicoronal, bicoronal, sagittal, lambdoid, expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, clinical reports from the American Academy of and frontosphenoidal) and their resultant head shape changes, with an Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the emphasis on differentiating conditions that require surgical correction from organizations or government agencies that they represent. -

Bagatelle Cassidy Syndrome: Macrocephaly

Journal of Clinical and Experimental Genetics Volume 1 | Issue 1 Case Report Open Access Bagatelle Cassidy Syndrome: Macrocephaly with Fronto-Facial Dysmorphism and Hearing Loss; an Extremely Rare Case Avina Fierro JA*1 and Hernandez Avina DA2 1Department of Pediatric Dysmorphology, IMSS Medical Center; Guadalajara, Mexico 2General Hospital Zona 2, IMSS Aguascalientes, Mexico *Corresponding author: Avina Fierro JA, Department of Pediatric Dysmorphology, IMSS Medical Center; Guadalajara, Mexico, Tel: (52)3336-743701, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Avina Fierro JA, Hernandez Avina DA (2015) Bagatelle Cassidy Syndrome: Macrocephaly with Fronto-Facial Dysmorphism and Hearing Loss; an Extremely Rare Case. J Clin Exp Gen 1(1): 101 Abstract Bagatelle Cassidy syndrome is a very rare disease first described in 1995 in a boy with macrocephaly, hypertelorism, hearing loss, developmental delay and facial dysmorphism. The cause of this syndrome is unknown and has no specific diagnostic test. We report the case of a 9-year-old girl with a cerebro-fronto-facial malformation syndrome with macrocephaly, with significant decrease of the hearing, moderate hearing loss (50 db HL at 4000 Hz); mild mental retardation (IQ 50) and noticeable speech delay, psychomotor and developmental delay. Facial anomalies show prominent forehead (frontal bossing) , hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures, flat nasal bridge, short nose with anteverted nostrils; broad columella, long smooth philtrum and carp-like mouth; this phenotype represents the specific -

RIN2 Deficiency Results in Macrocephaly, Alopecia, Cutis Laxa

REPORT RIN2 Deficiency Results in Macrocephaly, Alopecia, Cutis Laxa, and Scoliosis: MACS Syndrome Lina Basel-Vanagaite,1,2,14 Ofer Sarig,4,14 Dov Hershkovitz,6,7 Dana Fuchs-Telem,2,4 Debora Rapaport,3 Andrea Gat,5 Gila Isman,4 Idit Shirazi,4 Mordechai Shohat,1,2 Claes D. Enk,10 Efrat Birk,2 Ju¨rgen Kohlhase,11 Uta Matysiak-Scholze,11 Idit Maya,1 Carlos Knopf,9 Anette Peffekoven,12 Hans-Christian Hennies,12 Reuven Bergman,8 Mia Horowitz,3 Akemi Ishida-Yamamoto,13 and Eli Sprecher2,4,6,* Inherited disorders of elastic tissue represent a complex and heterogeneous group of diseases, characterized often by sagging skin and occasionally by life-threatening visceral complications. In the present study, we report on an autosomal-recessive disorder that we have termed MACS syndrome (macrocephaly, alopecia, cutis laxa, and scoliosis). The disorder was mapped to chromosome 20p11.21-p11.23, and a homozygous frameshift mutation in RIN2 was found to segregate with the disease phenotype in a large consan- guineous kindred. The mutation identified results in decreased expression of RIN2, a ubiquitously expressed protein that interacts with Rab5 and is involved in the regulation of endocytic trafficking. RIN2 deficiency was found to be associated with paucity of dermal micro- fibrils and deficiency of fibulin-5, which may underlie the abnormal skin phenotype displayed by the patients. Disorders of elastic tissue often share common phenotypic shown to result in decreased secretion of elastin.9,10 In features, including redundant skin, hyperlaxity of joints, addition, -

Congenital Anomalies and in Utero Antiretroviral Exposure in Human Immunodeficiency Virus– Exposed Uninfected Infants

Supplementary Online Content Williams PL, Crain MJ, Yildirim C, et al; Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study. Congenital anomalies and in utero antiretroviral exposure in human immunodeficiency virus– exposed uninfected infants. Published online November 10, 2014. JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1889. eTable 1. Frequency of Specific Major Congenital Anomalies Within Anomaly Categories eTable 2. Anomalies Reported Among Children Exposed to Atazanavir During the First Trimester eTable 3. Association of Timing of the First ARV Exposure During Pregnancy With Congenital Anomalies by ARV Drug Class and for Specific ARV Drugs This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/24/2021 eTable 1. Frequency of Specific Major Congenital Anomalies Within Anomaly Categories # of children with at Total # of least one major anomaly in Anomaly anomalies category Category (Total=242) (Total=201) List of Major Anomalies Musculoskeletal 72 59 Polydactyly (15), torticollis/muscular anomaly (12), clubfoot, talipes, other foot deformity (9), congenital dislocation of hip (5), craniosynostosis (4), plagiocephaly (4), pectus excavatum/funnel chest (3), lower limb anomaly (3), hypertelorism/other face or skull anomaly (3), spina bifida occulta/spine anomaly (3), syndactyly (3), inguinal hernia (2), diaphragmatic hernia/Morgagni, genu recurvatum/bowed legs, rib/sternum anomaly, scoliosis/congenital -

Amit C, Et Al. Functional Genomics Study of Sick Neonate Affected with Copyright© Amit C, Et Al

Genomics & Gene Therapy International Journal ISSN: 2642-1194 Functional Genomics Study of Sick Neonate Affected with Chromosomal Rearrangements and Correlated with Clinical Phenotype: A 2 Year Survey of ICU in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kolkata Puspal D1, Sudipa C1, Amit C1*, Tushar KS2 and Santanu B2 Research Article 1 Institute of Genetic Engineering, 30 Thakurhat Road, Kolkata-128, India Volume 1 Issue 1 2Dr. BC Roy Post Graduate Institute of Pediatric Science, Phoolbagan Main Road, Received Date: June 29, 2017 Kolkata-59, India Published Date: August 17, 2017 DOI: 10.23880/ggtij-16000101 *Corresponding author: Amit Chakravarty, Purbagana, 5 Ram Mohan Mallick Garden Lane, Beliaghata, Kolkata-10, India, Tel: 9903850960; Email: [email protected] . Abstract In order to assess major chromosomal abnormalities among sick neonate with dysmorphic feature, mental retardation and delayed milestones in Kolkata, a chromosome aberration survey initiated in collaboration with Dr B.C. Roy Post Graduate Institute for Pediatric Science (Kolkata) is in progress. Since two years, we have screened about 120 sick neonates and children with indicated cases as per clinical findings. Cytogenetic analysis of blood lymphocytes were studied with High Resolution GTG-banding analysis by using Chromosome profiling (Cyto-vision software 3.6) on their chromosomes. The result shows significant amount of numerical and structural chromosomal abnormality. Among 120 selected sick neonates with dysmorphic fatures and pediatric cases, 22 cases have different chromosomal abnormalities. Among them 14 cases have numerical and 8 cases have structural chromosomal abnormality. The present genetic screening result shows presence of syndromes caused by numerical chromosomal abnormality like Down Syndromes [1] Edwards syndrome, Patau syndrome, Turner syndrome [2] Sex Chromosomes [3] Others [1] and structural chromosome rearrangements [4]. -

Common Neonatal Syndromes

Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine (2005) 10, 221e231 www.elsevierhealth.com/journals/siny Common neonatal syndromes Mark H. Lipson* Department of Genetics, Permanente Medical Group, Sacramento, CA, USA KEYWORDS Summary The process of diagnosis of genetic syndromes in the newborn period is Fluorescence in situ carried out in the context of parental anxiety and the grief following an often- hybridisation (FISH); unexpected outcome after a long pregnancy. The nursery staffs invariably have Telomere; a strong interest in giving the family proper information about prognosis. This Uniparental disomy; article is intended to focus on an approach to the diagnosis of genetic syndromes Imprinting and to discuss specific syndromes that may be seen with some frequency in the nursery. Ó 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. A baby has just been born. The exhausted but a geneticist or genetics centre is essential at some jubilant parents are finally able to see the result of point in the diagnostic process. A diagnosis is not the previous 9 months of morning sickness, weight the end of the process but merely the beginning. gain and water retention. But instead of unmiti- Genetic counseling is a process whereby a con- gated excitement and happiness, there is fear, firmed or possible genetic condition is reviewed uncertainty and disbelief. The reaction of the with the family, and the etiology, natural history, nurses and doctors has indicated that there is prognosis, treatment possibilities, risk of recur- a problem with the baby. What does it mean? Will rence, potential for prenatal diagnosis and the the baby be OK? What can be done to correct the availability of pertinent reading materials and problem? It is in this context that syndrome support groups are discussed at length.