Rape Victims in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5134Payments

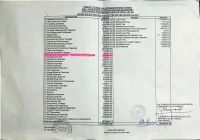

ПАТНАР FOUNOAT10NFOR EOUCATlON $ND TRAIN'NG OF АМОMANAGEMENT САМИ}, мупом. носн! • 683 lNCOMEАНО AccQtJNT FQR твр УЕАВ ЕНОЕО314-2020 EXPENOlTUR lNCOME То Satahesand Albwances 33197035.оо ву Тишоп Fee 131462874.23 Taxes То Ren(R3tes and 627656.ОО Ву Registration Fee 710115.00 То ТгачеШпд Expenses 555676ђ.оо Ву Hostel Fee Б159085.СО То P'.-intingand Stationery 922477.oo Ву Wscellaneous lncome 335194.00 E»enses То Advertisernent 3917809.00 Ву lnterest Receivedfrom Fixed Deposit 3007621 .oo and Telesram То Postage.Teiephone 443457.49 Ву tncome from Reprographics 5515.00 PeriQdicats То New•spapersand 227249.oo Ву Identity Card Fee 175800.00 о Suesctip)on 469706.oo Ву University Sports Atflliation Fee 89070. ОО о 0ffce Expenses 2730499.оо Ву Interest received{гот other Deposits 106409.00 То Electricity and Watet Charge± 7081001.оо Ву Aluminl Fee 160200.oo Тс Repairs апа Maintenance 9237919.оо Ву 1псота {гот Funded Projects 397595.00 То Vehide Maintenance Charges 1233350.оо Ву Certiftcation Fee 1039663.00 Charges То Conveyance 306219.оо Ву Rent Received 100000.00 То Sernhar and Соп[егелсе Expenses 23712049 То Fees and Chxses 170796550 То Interest and Валк Charges 163442.76 Ртодгатте (РОР)Exp•nsec 960997,00 То ОспаЕопала Gift 446980.оо То Ptacement Expenses 3567741.oo То GeneraI tnsurance 460715.оо То Заг<ел E»enses 3335176.оо То Hcstel E.venses 2320379.oo То S:atf WeEare Expenses 43033.оо То Expenses 29*13.00 То Hcuse keeping Expenses 274369&00 То CSSR Expeases 74190.оо То Examhaticn Expease 314406.оо То Medical Expenses То Facutty0eveiopment -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Idukki District from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Idukki district from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THUNDATHIL HOUSE ( CHENNAMKOTTIL HOUSE) 23-01-2021 KARIMANNO 46, UDUMBANNOOR PO CHATHANMAL at 23:40 39/2021 U/s OR (Idukki BAILED BY 1 BIJO JOSEPH Male ,CHATHANMALA A Hrs 151 CrPC district) V.C JOHN POLICE KANJIKUZHY VILLAGE,PAZHAYARIK ANDAM KARAYIL PONNEDUTHAN 33/2021 U/s BHAGATHU 23-01-2021 279 IPC & 3(1) KANJIKUZHY GOPI S/O 55, PUTHANPURAYIL at 07:25 r/w 181 MV (Idukki ARRESTED -BY 2 KUTTAPPAN KUTTAPPAN Male VEEDU VARAKULAM Hrs Act district) SI KJ FRANCIS POLICE Varickakkal h, 23-01-2021 ADIMALI 35, murikkassery, at 19:35 40/2021 U/s (Idukki BAILED BY 3 Noby Augustine Male vathikkudi Adimaly Hrs 15(c) abkari act district) S Sivalal,si POLICE 23/2021 U/s 23-01-2021 279 IPC and VANDANMED Jayakrishnan Si 45, Chenakathil Amayar at 20:00 3(1) r/w 181 of U (Idukki of police BAILED BY 4 Johnson Muthuswamy Male Vandanmedu Mali Hrs MV act district) vandanmedu POLICE Thrittayil (h) Mavadi 18/2021 U/s kara ,Pnnamala 23-01-2021 279 IPC & 3(1) MURIKKASSE 26, bhagam Kalkoonthal at 18:58 r/w 181 MV RY (Idukki JOHNSON BAILED BY 5 Nibin Kuriyan Male Village Murickassery Hrs Act district) SAMUEL POLICE 35/2021 U/s U/S 188,269,270 OF IPC 118 (e) kochupurakkal h 23-01-2021 of kp act 5 r/w SANTHANPAR 32, thalakodu at 14:10 4 (2)(a) of kedo A (Idukki shaji kc si of BAILED BY 6 basil kp paili Male neriamangalam ekm suryanelli Hrs 2020 district) police POLICE Kalarikunnel veedu 23-01-2021 24/2021 U/s VANDIPERIYA 29, glanmary estate at 17:10 279 ipc146 r/w R (Idukki T. -

State of Kerala & Mahe District of UT of Puducherry In

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships - State of Kerala & Mahe District of UT of Puducherry Indian Oil Corporation proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in the State of Kerala & Mahe District of UT of Puducherry, as per following details: Minimum Dimension Finance to be Fixed fee/Minimum Bid Estimated monthly Type of Mode of Security deposit Sl. Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category (in M.)/Area of the site arranged amont sales Potential # site* Selection (Rs in lakhs) No. ( in Sq.M.)* by the Applicant (Rs. In lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Regular/Rural MS + HSD in Kls SC, SC Cc1, CC/DC/CFS Frontage Depth Area Estimated Estimated fund Draw of Lots/Bidding SC CC2,SC PH, working capital required for ST, ST CC1, ST requirement for development of CC2, ST PH, operation of infrastructure OBC, OBC Cc1, RO at RO OBC CC2, OBC PH, OPEN, OPEN CC1, OPEN CC2, OPEN PH 1 Punnumoodu Alappuzha Regular 160 SC CFS 25 25 625 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 2 Mararikulam to Thaikkal Beach on SH 66 Alappuzha Regular 130 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 3 Kavalam - Kidangara Road Alappuzha Rural 100 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 4 Angamaly Jn - Adlux International (NH - LHS) Ernakulam Regular 150 SC CFS 35 45 1575 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 5 Kunnumpuram Jn, Kakkanad to Thrikkakara Ernakulam Regular 160 SC CFS 25 25 625 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 on Kunnumpuram NGO Quarters Road 6 Fort Kochi to Mattancherry Ernakulam Regular 160 SC CFS 25 25 625 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 7 Puthencruz to Kolenchery Ernakulam Regular -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MIND THE

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MIND THE GAP: CONNECTING NEWS AND INFORMATION TO BUILD AN ANTI-RAPE AND SEXUAL ASSAULT AGENDA IN INDIA Pallavi Guha, Doctor of Philosophy, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Professor Kalyani Chadha, Philip Merrill College of Journalism Professor Linda Steiner, Philip Merrill College of Journalism This dissertation will examine the use of news media and social media platforms by feminist activists in building an anti-rape and sexual assault agenda in India. Feminist campaigns need to resonate and interact with the mainstream media and social media simultaneously to reach broader audiences, including policymakers, in India. For a successful feminist campaign to take off in a digitally emerging country like India, an interdependence of social media conversations and news media discussions is necessary. The study focuses on the theoretical framework of agenda building, digital feminist activism, and hybridization of the media system. The study will also introduce the still-emerging concept of interdependent agenda building to analyze the relationship between news media and social media. This concept proposes the idea of an interplay of information between traditional mass media and social media, by focusing not just on one media platform, but on multiple platforms simulataneous in this connected world. The methodology of the study includes in-depth interviews with thirty-five feminist activists and thirty journalists; thematic analysis of 550 newspaper reports of three rapes and murders from 2005-2016; and social media analysis of three Facebook feminist pages to understand and analyze the impact of social media on news media coverage of rape and the combined influence of media platforms on anti-rape feminist activism. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Idukki District from 20.09.2020To26.09.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Idukki district from 20.09.2020to26.09.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 OZHUKAYIL HOUSE, 20-09-2020 1283/2020 ARRESTED - 39, Ozhuvathada ADIMALI JUDY TP SI 1 SHAIES JOY MANKUVA, at 00:30 U/s 457, 380 JFMC Male m (Idukki ) ADIMALY KONNATHADY Hrs IPC ADIMALY VILLAGE Thazhethuruthiyil house, 20-09-2020 Prasanth P. 37, 825/2020 U/s KUMILY BAILED BY 2 Shihabudeen Ismail Karuppupalam, Kumily at 11:00 Nair, SI Male 279, 337 IPC (Idukki ) POLICE Vandiperiyar, Hrs Kumily Periyar village velikkakathu house, IDUKKI 1095/2020 20-09-2020 ARRESTED - 37, nayarupaara PO ,THANKAM U/s IDUKKI 3 SANOJ BABY at 12:05 SAGAR MP JFMC Male THANKAMANY ANI 55(a)&55(i) of (Idukki ) Hrs IDUKKI VILLAGE, IDUKKI VILLEGE Abkari Act PUSHPAKATTUKA LAYIL (H),AYARKKUNN 433/2020 U/s AM 20-09-2020 SABU K S, S I 38, 279 IPC,179 KULAMAV BAILED BY 4 BINU BENADICT KARA,ELAPPANI ARUVIPARA at 12:20 OF POLICE, Male (1) OF MV U (Idukki ) POLICE BAGHAM,AYARK Hrs KULAMAVU ACT KUNNAM VILLAGE ,KOTTAYAM DIST 1284/2020 Ayvanakudiyil (H) U/s 6(b) 20-09-2020 ARRESTED - Saidhmuham 42, ozhuvathadam Irumpupal R/W 24 of ADIMALI S.sivalal si of 5 shemeer at 12:50 JFMC med Male valara P.0 am codpa (Idukki ) police Hrs ADIMALY Irumpupalam act&118(1) KP act KALAPPURAKKAL IN HOUSE 20-09-2020 888/2020 U/s KARIMAN JUDICIAL -

Rs .0 Destinations Overview Itinerary

0484 4020030, 8129114245 [email protected] WESTERN GHATS NATURE TRAIL Rs .0 3 Nights 4 Days Destinations Munnar , Suryanelli, Kolukumalai Overview Places Covered :- Munnar (2N), Suryanelli, Kolukumalai Itinerary Day 1 : Munnar ( Meal plan: Breakfast ) Meet and get greeted by your driver cum guide at Cochin international Airport. After short briefing, get transffered to Suryanelli via Munnar.enroute visit Kodanadu elephant training centre. You will be taking a spectacular 4 hour drive along the climbing road, through forests and tea gardens, to the hill station of Munnar which is situated 1500 metres high in the mountains. The combination of crisp mountain air, craggy peaks and tall red wood trees make it a peaceful retreat. Here, endemic species of birds & animals find their home. Continue your journey past valara, Cheeyappara Waterfalls, tea plantations, spice plantations, Veg farms before you reach Munnar. Kathakali dance performance in Munnar. Check –into Hotel . Rest of the day at leisure. Overnight : 3* category hotel Day 2 : Munnar ( Meal Plan : Breakfast ) After breakfast, get transferred to Top station located around 32 km away from Munnar, the highest point (1700m) in Munnar, on the Munnar-Kodaikkanal road. The place falls on the Kerala-Tamil Nadu border. Here you can enjoy the panoramic view of Western Ghats and the valley of Theni district of Tamil Nadu. View the mountains filled in mist and start your journey to eco point Scenic spot on a reservoir featuring an echo phenomenon, visit Mattupetty dam, taste some fresh carrots, strawberries etc. Spend some time there and start your Jounery back to Hotel, enroute do some window shopping . -

Idukki-District-Migration-Profile-CMID.Pdf

District Migration Profile Idukki Benoy Peter and Vishnu Narendran Savanan R.S.Savanan Labour Migration to Kerala to Labour Migration cmid.org.in The reluctance of younger Tamilians to do low-valued jobs in the recent past has paved the way for migrants from other states entering the Idukki labour market. Savanan R.S.Savanan dukki is famous for its plantations, tourist destinations and unit in Thodupuzha. All these industries depend heavily on hydroelectric projects. The district comprises Devikulam, migrant labour. IUdumbanchola, Peerumedu and Thodupuzha taluks. Peerumedu and Devikulam taluks are known for the tea plantations while Plantations Udumbanchola is popular for cardamom. Munnar and Thekkady are Idukki is the cradle of plantation crops in Kerala. Tea, cardamom, the tourist hot spots in the district. Industrially backward, agriculture rubber and coffee are the major crops. Though the migrants from is the chief occupation of the people in this district. Plantations and northern and eastern Indian states are not skilled enough to work in hospitality sectors now depend on labourers from north, central, these plantations, the shortage of labour has been forcing plantation east and northeast India. Being a district bordering Tamil Nadu state, managements to hire them. These plantations also hire people from migration of Tamil labourers has been going on for decades. The Tamil Nadu. A significant proportion of Tamil workers commute reluctance of younger Tamilians to do low-valued jobs in the recent daily to the plantations in jeeps from their home districts adjacent to past has paved the way for migrants from other states entering the Idukki. -

A4 Brochure 2021 Lowres.Cdr

Santos King INDIA SOUTH INDIA GOA KARNATAKA ANDAMAN AND TAMIL NICOBAR ISLANDS NADU LAKSHADWEEP KERALA SOUTH OF INDIA world and one of the UNESCO World Heritage. SANTOS KING The region is home to one of the largest Santos King is an independent tour operator with South India is a peninsula in the shape of an populations of endangered Indian elephants and offices in Kochi and Alappuzha specializing in all inverted triangle bound by the Arabian sea on the Bengal tiger in India. South India Holiday Packages, Houseboat cruises west, by the Bay of Bengal on the east and Vindhya and Satpura ranges on the north. The Western South India consists of five southern Indian states and Adventure tour activities. Founded in 2009 by a Ghats run parallel along the western coast and a of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil group of professionals with rich experience in the narrow strip of the land between the Western Nadu and Kerala with union territories of tourism industry, Santos King aims to provide Ghats and the Arabian sea forms the Konkan Puducherry, Lakshadweep and Andaman & excellent service to its clients and hassle-free region. The Western Ghats continue south until Nicobar Islands. operations for the tour operators. Kanyakumari. The Eastern Ghats run parallel along the eastern coast and the strip of land The traditional music of South India is known as We have provided our service to a lot of between the Eastern ghats and the Bay of Bengal Carnatic music. South India is home to several international groups in the last 7 years with most of forms the Coromandel coast. -

Rajagiri Highlights Oct-December 2013.Pmd

1 Rajagiri National Youth Meet organized for graduates Vigilance Department, Government of Kerala was the and professionals across the country was held on 20th Chief Guest for the valedictory function and Mr. Ravi and 21st November 2013 at Kakkanad campus. The Shankar - the General Manager of Lakshmi Vilas Bank formal Inauguration of the Youth Meet was by Prof. P.J was the Guest of Honor. The quiz master was Mr. Rohit Kurien, Hon’ble Deputy Chairman of Rajya Sabha. The Nair of ‘Quiz Works’.The media partner CNN-IBN aired meet attracted a total of 73 participants from different the programme on December 22, 2013. states. Rajagiri Inflore: Rajagiri Centre for Business Studies conducted the two day INFLORE management fest on International Students; Interactive Programme: November 21 and 22, 2013. The Chief Guest was Shri. was held on November 18, 2013. The Confederation of Nikhil Kumar, Hon’ble Governor of Kerala. 819 students Indian Industry (CII) organised the visit from ASEAN from 101 institutions participated. Students delegation from Vietnam, Thailand. This visit was a follow through of Hon’ble Prime Minister, Dr Manmohan Singh’s invitation at the 5th India - ASEAN Summit, for students to experience the sights and sounds of ancient India and to experience first-hand the modern resurging India. A total of 50 International students from the ASEAN Nations of Vietnam & Thailand visited our campus. They made presentations and shared their experiences. The delegation was devoted on interacting with Rajagiri Business School officials as well as learn more about the educational system prevailing in the country. Rajagiri National Business Quiz 2013: The highlight of INFLORE 2013 was the Rajagiri National Business Quiz, for both students & corporates from all over India.