Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minority Media and Community Agenda Setting a Study on Muslim Press in Kerala

Minority Media and Community Agenda Setting A Study On Muslim Press In Kerala Muhammadali Nelliyullathil, Ph.D. Dean, Faculty of Journalism and Head, Dept. of Mass Communication University of Calicut, Kerala India Abstract Unlike their counterparts elsewhere in the country, Muslim newspapers in Kerala are highly professional in staffing, payment, and news management and production technology and they enjoy 35 percent of the newspaper readership in Kerala. They are published in Malayalam when Indian Muslim Press outside Kerala concentrates on Urdu journalism. And, most of these newspapers have a promising newsroom diversity employing Muslim and non-Muslim women, Dalits and professionals from minority and majority religions. However, how effective are these newspapers in forming public opinion among community members and setting agendas for community issues in public sphere? The study, which is centered on this fundamental question and based on the conceptual framework of agenda setting theory and functional perspective of minority media, examines the role of Muslim newspapers in Kerala in forming a politically vibrant, progress oriented, Muslim community in Kerala, bringing a collective Muslim public opinion into being, Influencing non-Muslim media programming on Muslim issues and influencing the policy agenda of the Government on Muslim issues. The results provide empirical evidences to support the fact that news selection and presentation preferences and strategies of Muslim newspapers in Kerala are in line with Muslim communities’ news consumption pattern and related dynamics. Similarly, Muslim public’s perception of community issues are formed in accordance with the news framing and priming by Muslim newspapers in Kerala. The findings trigger more justifications for micro level analysis of the functioning of the Muslim press in Kerala to explore the community variable in agenda setting schema and the significance of minority press in democratic political context. -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

5134Payments

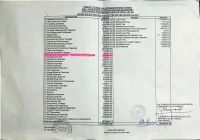

ПАТНАР FOUNOAT10NFOR EOUCATlON $ND TRAIN'NG OF АМОMANAGEMENT САМИ}, мупом. носн! • 683 lNCOMEАНО AccQtJNT FQR твр УЕАВ ЕНОЕО314-2020 EXPENOlTUR lNCOME То Satahesand Albwances 33197035.оо ву Тишоп Fee 131462874.23 Taxes То Ren(R3tes and 627656.ОО Ву Registration Fee 710115.00 То ТгачеШпд Expenses 555676ђ.оо Ву Hostel Fee Б159085.СО То P'.-intingand Stationery 922477.oo Ву Wscellaneous lncome 335194.00 E»enses То Advertisernent 3917809.00 Ву lnterest Receivedfrom Fixed Deposit 3007621 .oo and Telesram То Postage.Teiephone 443457.49 Ву tncome from Reprographics 5515.00 PeriQdicats То New•spapersand 227249.oo Ву Identity Card Fee 175800.00 о Suesctip)on 469706.oo Ву University Sports Atflliation Fee 89070. ОО о 0ffce Expenses 2730499.оо Ву Interest received{гот other Deposits 106409.00 То Electricity and Watet Charge± 7081001.оо Ву Aluminl Fee 160200.oo Тс Repairs апа Maintenance 9237919.оо Ву 1псота {гот Funded Projects 397595.00 То Vehide Maintenance Charges 1233350.оо Ву Certiftcation Fee 1039663.00 Charges То Conveyance 306219.оо Ву Rent Received 100000.00 То Sernhar and Соп[егелсе Expenses 23712049 То Fees and Chxses 170796550 То Interest and Валк Charges 163442.76 Ртодгатте (РОР)Exp•nsec 960997,00 То ОспаЕопала Gift 446980.оо То Ptacement Expenses 3567741.oo То GeneraI tnsurance 460715.оо То Заг<ел E»enses 3335176.оо То Hcstel E.venses 2320379.oo То S:atf WeEare Expenses 43033.оо То Expenses 29*13.00 То Hcuse keeping Expenses 274369&00 То CSSR Expeases 74190.оо То Examhaticn Expease 314406.оо То Medical Expenses То Facutty0eveiopment -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

RLI-Electronic Insurance Coverage Report-Kerala

RELIANCE LIFE INSURANCE TIES UP WITH INSURANCE REPOSITORIES TO OFFER ELECTRONIC INSURANCE POLICIES MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT KERALA COVERAGE SYNOPSIS RLI-ELECTRONIC INSURANCE POLICIES COVERAGE DETAILS KOCHI S.No. Publications Language Circulation Date 1. Deccan Chronicle English 35000 28/11/2013 2. HBL English 25000 02/12/2013 3. HBL English 25000 02/12/2013 4. HBL English 25000 04/12/2013 5. Financial Express English 12000 28/11/2013 6. Malayala Manorama Malayalam 305600 06/12/2013 7. Matrubhoomi Malayalam 145698 05/12/2013 8. Veekshanam Malayalam 38454 03/12/2013 9. Deshabhimaani Malayalam 41677 08/12/2013 10. Chandrika Malayalam 42708 03/12/2013 11. Vaarthamanam Malayalam 35000 05/12/2013 12. Siraj Malayalam 25456 08/12/2013 13. Kerala Kaumudi Malayalam 22836 03/12/2013 14. Metro Vaartha Malayalam 75000 14/12/2013 TOTAL 854429 KOCHI MEDIA COVERAGE Publication Deccan Chronicle Date 28th November, 2013 Page No 12 Edition Kochi Headline RLIC TIES UP WITH REPOSITORIES Publication Hindu Business Line Date 2nd December, 2013 Page No 01 Edition Kochi Headline RELIANCE LIFE TIES UP WITH REPOSITORIES Publication Hindu Business Line Date 2nd December, 2013 Page No 05 Edition Kochi Headline RELIANCE LIFE TIES UP WITH INSURANCE REPOSITORIES Publication Hindu Business Line Date 4th December, 2013 Page No 17 Edition Kochi Headline RELIANCE LIFE TIES UP WITH INSURANCE REPOSITORIES Publication The Financial Express Date 28th November, 2013 Page No 08 Edition Kochi Headline RELIANCE LIFE TIES UP WITH FIVE INSURANCE REPOSITORIES Publication Malayala Manorama -

Magazine Journalism

What is Magazine? The Word Magazine is coined by the Edward Cave. It is derived from Arabic word ‘makhazin’ which means storehouse- all bundled together in one package. A magazine can be explained as a periodical that contains a variety of articles as well as illustrations, which are of entertaining, promotional and instructive nature. It generally contains essays, stories, poems, articles, fiction, recipes, images etc. and offers a more comprehensive, in-depth coverage and analysis of subject than newspapers. Most of magazines generally cover featured articles on various topics. Magazines are typically published weekly, bi-weekly, monthly, bi-monthly or quarterly. They are often printed in colour on coated paper and are bound with a soft cover. In a simple, we can say that ‘the better the visual narrative of the magazine, the more it will appeal to its specific audience’. The publisher’s purpose for a magazine is to give its advertisers a chance to share with its readers about their products. Magazine Journalism Magazine Journalism uses the similar tools as traditional journalism tools used for gathering information, background research and writing to produce articles for consumer and trade magazines. The cover story is the beacon in any magazine. The cover page quite often carries stunning headlines to facilitate a compulsive buying of the magazine. Vanitha : An Indian Magazine Vanitha is an Indian magazine published fortnightly by the Malayala Manorama group. Vanitha in Malayalam means woman. It was launched in 1975 as a monthly and later become fortnightly in 1987. Its Hindi edition was launched in 1997. It has a readership of over 3.7 million, making it fifth highest read magazine in India. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

Rape Victims in Kerala

Rape Victims in Kerala Usha Venkitakrishnan Sunil George Kurien Discussion Paper No. 52 Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development Centre for Development Studies Thiruvananthapuram Rape Victims in Kerala Usha Venkitakrishnan, Sunil George Kurien English Discussion Paper Rights reserved First published 2003 Editorial Board: Prof. P. R. Gopinathan Nair, H. Shaji Printed at: Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development Published by: Dr K. N. Nair, Programme Co-ordinator, Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development, Centre for Development Studies, Prasanth Nagar, Ulloor, Thiruvananthapuram 695 011 Tel: 0471-2550 465, 2550 427 Fax: 0471-2550 465 E-mail: [email protected] www.krpcds.org Cover Design: Defacto Creations ISBN No: 81-87621-55-9 Price: Rs 40 US$ 5 KRPLLD 2003 0650 ENG 2 Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. A Short Survey of Literature on Rape 9 3. The Background: Growth of rape cases in India and Kerala 21 4. Rape Episodes in Kerala 33 5. Rape Victims and Rapists 39 6. Police, Judiciary, and Medical Personnel 53 7. Conclusions and Suggestions 58 3 4 Rape Victims in Kerala Usha Venkitakrishnan, Sunil George Kurien 1. Introduction Gender discrimination is a universal phenomenon. Discrimination against women is more predominant in Asian countries. The Report on Human Development in South Asia (2001) underlines the inherent sex discrimination that exists in Asian society. Gender-biased customs, beliefs, superstitions, behavioural training, and mythology are used as tools to subjugate women and maintain them in oppression. Though all human beings are born with equal physical and mental capability and potential, men, who are in power and authority, which is the hallmark of patriarchy, suppress women. -

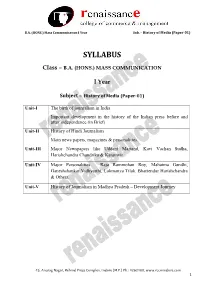

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). -

Accused Persons Arrested in Idukki District from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Idukki district from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THUNDATHIL HOUSE ( CHENNAMKOTTIL HOUSE) 23-01-2021 KARIMANNO 46, UDUMBANNOOR PO CHATHANMAL at 23:40 39/2021 U/s OR (Idukki BAILED BY 1 BIJO JOSEPH Male ,CHATHANMALA A Hrs 151 CrPC district) V.C JOHN POLICE KANJIKUZHY VILLAGE,PAZHAYARIK ANDAM KARAYIL PONNEDUTHAN 33/2021 U/s BHAGATHU 23-01-2021 279 IPC & 3(1) KANJIKUZHY GOPI S/O 55, PUTHANPURAYIL at 07:25 r/w 181 MV (Idukki ARRESTED -BY 2 KUTTAPPAN KUTTAPPAN Male VEEDU VARAKULAM Hrs Act district) SI KJ FRANCIS POLICE Varickakkal h, 23-01-2021 ADIMALI 35, murikkassery, at 19:35 40/2021 U/s (Idukki BAILED BY 3 Noby Augustine Male vathikkudi Adimaly Hrs 15(c) abkari act district) S Sivalal,si POLICE 23/2021 U/s 23-01-2021 279 IPC and VANDANMED Jayakrishnan Si 45, Chenakathil Amayar at 20:00 3(1) r/w 181 of U (Idukki of police BAILED BY 4 Johnson Muthuswamy Male Vandanmedu Mali Hrs MV act district) vandanmedu POLICE Thrittayil (h) Mavadi 18/2021 U/s kara ,Pnnamala 23-01-2021 279 IPC & 3(1) MURIKKASSE 26, bhagam Kalkoonthal at 18:58 r/w 181 MV RY (Idukki JOHNSON BAILED BY 5 Nibin Kuriyan Male Village Murickassery Hrs Act district) SAMUEL POLICE 35/2021 U/s U/S 188,269,270 OF IPC 118 (e) kochupurakkal h 23-01-2021 of kp act 5 r/w SANTHANPAR 32, thalakodu at 14:10 4 (2)(a) of kedo A (Idukki shaji kc si of BAILED BY 6 basil kp paili Male neriamangalam ekm suryanelli Hrs 2020 district) police POLICE Kalarikunnel veedu 23-01-2021 24/2021 U/s VANDIPERIYA 29, glanmary estate at 17:10 279 ipc146 r/w R (Idukki T. -

Research Report on Consumer Behaviour the We Ek

RESEARCH REPORT ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR THE WE EK Journalism with a human touch Submitted To: - Submitted By: - Declaration The project report entitled is submitted to in partial fulfillment of “post graduate diploma in management”. The report is exclusively and comprehensively prepared and conceptualized by me. All the information and data given here in this project is as per my fullest knowledge collected during my studies and from the various websites. The report is an original work done by me and it has not formed the basis for the award of any other degree or diploma elsewhere. Place : LUCKNOW AJAY SINGH Date : ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The project report is a result of our rigorous and devoted effort and valuable guidance of Mr.sanjeev Sharma, Mr.Sandeep and it is the result of the traning in malayala manorama, it contains brief history of the organization and its mission / objectives. Malayala manorama is a well known name for its valuable services. The organization is maintaining the quality of the services throughout. I have done my project in malayala manorama, Lucknow. The focus of the project is overview of the various aspects of services basically in Consumer Buying behavior. This project as a summer traning is a partial fulfillment of two year MBA course. In this project we have strived to include all the details regarding the subject and made a sincere effort towards completion of the same. In this course of training we learned various pratical aspects about the Consumer Buying Behaviour and we knew about the major benefits provided by malayala manorama to their consumers & to the society.