ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MIND THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5134Payments

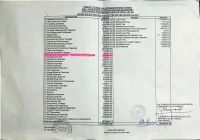

ПАТНАР FOUNOAT10NFOR EOUCATlON $ND TRAIN'NG OF АМОMANAGEMENT САМИ}, мупом. носн! • 683 lNCOMEАНО AccQtJNT FQR твр УЕАВ ЕНОЕО314-2020 EXPENOlTUR lNCOME То Satahesand Albwances 33197035.оо ву Тишоп Fee 131462874.23 Taxes То Ren(R3tes and 627656.ОО Ву Registration Fee 710115.00 То ТгачеШпд Expenses 555676ђ.оо Ву Hostel Fee Б159085.СО То P'.-intingand Stationery 922477.oo Ву Wscellaneous lncome 335194.00 E»enses То Advertisernent 3917809.00 Ву lnterest Receivedfrom Fixed Deposit 3007621 .oo and Telesram То Postage.Teiephone 443457.49 Ву tncome from Reprographics 5515.00 PeriQdicats То New•spapersand 227249.oo Ву Identity Card Fee 175800.00 о Suesctip)on 469706.oo Ву University Sports Atflliation Fee 89070. ОО о 0ffce Expenses 2730499.оо Ву Interest received{гот other Deposits 106409.00 То Electricity and Watet Charge± 7081001.оо Ву Aluminl Fee 160200.oo Тс Repairs апа Maintenance 9237919.оо Ву 1псота {гот Funded Projects 397595.00 То Vehide Maintenance Charges 1233350.оо Ву Certiftcation Fee 1039663.00 Charges То Conveyance 306219.оо Ву Rent Received 100000.00 То Sernhar and Соп[егелсе Expenses 23712049 То Fees and Chxses 170796550 То Interest and Валк Charges 163442.76 Ртодгатте (РОР)Exp•nsec 960997,00 То ОспаЕопала Gift 446980.оо То Ptacement Expenses 3567741.oo То GeneraI tnsurance 460715.оо То Заг<ел E»enses 3335176.оо То Hcstel E.venses 2320379.oo То S:atf WeEare Expenses 43033.оо То Expenses 29*13.00 То Hcuse keeping Expenses 274369&00 То CSSR Expeases 74190.оо То Examhaticn Expease 314406.оо То Medical Expenses То Facutty0eveiopment -

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India Vani K. Borooah, Amaresh Dubey and Sriya Iyer ABSTRACT This article investigates the effect of jobs reservation on improving the eco- nomic opportunities of persons belonging to India’s Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). Using employment data from the 55th NSS round, the authors estimate the probabilities of different social groups in India being in one of three categories of economic status: own account workers; regu- lar salaried or wage workers; casual wage labourers. These probabilities are then used to decompose the difference between a group X and forward caste Hindus in the proportions of their members in regular salaried or wage em- ployment. This decomposition allows us to distinguish between two forms of difference between group X and forward caste Hindus: ‘attribute’ differences and ‘coefficient’ differences. The authors measure the effects of positive dis- crimination in raising the proportions of ST/SC persons in regular salaried employment, and the discriminatory bias against Muslims who do not benefit from such policies. They conclude that the boost provided by jobs reservation policies was around 5 percentage points. They also conclude that an alterna- tive and more effective way of raising the proportion of men from the SC/ST groups in regular salaried or wage employment would be to improve their employment-related attributes. INTRODUCTION In response to the burden of social stigma and economic backwardness borne by persons belonging to some of India’s castes, the Constitution of India allows for special provisions for members of these castes. -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

Gendered Violence and India's Body Politic

manali desai GENDERED VIOLENCE AND INDIA’S BODY POLITIC he paradox of rape is that it has a long history and occurs across all countries, yet its meaning can best be grasped through an analysis of specific social, cultural and political environments. Feminist writing on citizenship and the state Thas long noted the relevance of women’s bodies as reproducers of the nation; it is equally important to think about the uses of the sexed body in a political context. A consideration of gendered violence as part of a continuum of embodied assertions of power can not only tell us how masculine supremacy is perpetuated through tolerated repertoires of behaviour, but also help us to understand how forms of class, kinship and ethnic domination are secured—and what happens when they are disrupted. Rape, Joanna Bourke has observed, is a form of social perfor- mance, the ritualized violation of another sexed body.1 This is no less true for such apparently depoliticized though grievous forms of violence as the now infamous gang rape of Jyoti Singh, a young woman returning from a night out in New Delhi in December 2012. In a country where complacency about sexual assault has been the norm, the uproar that followed suggested that an unspoken limit had been crossed. Mass protests across India expressed a very political and public anger with the institutional apathy and impunity of the estab- lishment. The mobilization of feminist groups and youth during this episode succeeded in generating a momentum for change, not least by challenging the stigma associated with reporting rape. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Rape Victims in Kerala

Rape Victims in Kerala Usha Venkitakrishnan Sunil George Kurien Discussion Paper No. 52 Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development Centre for Development Studies Thiruvananthapuram Rape Victims in Kerala Usha Venkitakrishnan, Sunil George Kurien English Discussion Paper Rights reserved First published 2003 Editorial Board: Prof. P. R. Gopinathan Nair, H. Shaji Printed at: Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development Published by: Dr K. N. Nair, Programme Co-ordinator, Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development, Centre for Development Studies, Prasanth Nagar, Ulloor, Thiruvananthapuram 695 011 Tel: 0471-2550 465, 2550 427 Fax: 0471-2550 465 E-mail: [email protected] www.krpcds.org Cover Design: Defacto Creations ISBN No: 81-87621-55-9 Price: Rs 40 US$ 5 KRPLLD 2003 0650 ENG 2 Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. A Short Survey of Literature on Rape 9 3. The Background: Growth of rape cases in India and Kerala 21 4. Rape Episodes in Kerala 33 5. Rape Victims and Rapists 39 6. Police, Judiciary, and Medical Personnel 53 7. Conclusions and Suggestions 58 3 4 Rape Victims in Kerala Usha Venkitakrishnan, Sunil George Kurien 1. Introduction Gender discrimination is a universal phenomenon. Discrimination against women is more predominant in Asian countries. The Report on Human Development in South Asia (2001) underlines the inherent sex discrimination that exists in Asian society. Gender-biased customs, beliefs, superstitions, behavioural training, and mythology are used as tools to subjugate women and maintain them in oppression. Though all human beings are born with equal physical and mental capability and potential, men, who are in power and authority, which is the hallmark of patriarchy, suppress women. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Accused Persons Arrested in Idukki District from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Idukki district from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THUNDATHIL HOUSE ( CHENNAMKOTTIL HOUSE) 23-01-2021 KARIMANNO 46, UDUMBANNOOR PO CHATHANMAL at 23:40 39/2021 U/s OR (Idukki BAILED BY 1 BIJO JOSEPH Male ,CHATHANMALA A Hrs 151 CrPC district) V.C JOHN POLICE KANJIKUZHY VILLAGE,PAZHAYARIK ANDAM KARAYIL PONNEDUTHAN 33/2021 U/s BHAGATHU 23-01-2021 279 IPC & 3(1) KANJIKUZHY GOPI S/O 55, PUTHANPURAYIL at 07:25 r/w 181 MV (Idukki ARRESTED -BY 2 KUTTAPPAN KUTTAPPAN Male VEEDU VARAKULAM Hrs Act district) SI KJ FRANCIS POLICE Varickakkal h, 23-01-2021 ADIMALI 35, murikkassery, at 19:35 40/2021 U/s (Idukki BAILED BY 3 Noby Augustine Male vathikkudi Adimaly Hrs 15(c) abkari act district) S Sivalal,si POLICE 23/2021 U/s 23-01-2021 279 IPC and VANDANMED Jayakrishnan Si 45, Chenakathil Amayar at 20:00 3(1) r/w 181 of U (Idukki of police BAILED BY 4 Johnson Muthuswamy Male Vandanmedu Mali Hrs MV act district) vandanmedu POLICE Thrittayil (h) Mavadi 18/2021 U/s kara ,Pnnamala 23-01-2021 279 IPC & 3(1) MURIKKASSE 26, bhagam Kalkoonthal at 18:58 r/w 181 MV RY (Idukki JOHNSON BAILED BY 5 Nibin Kuriyan Male Village Murickassery Hrs Act district) SAMUEL POLICE 35/2021 U/s U/S 188,269,270 OF IPC 118 (e) kochupurakkal h 23-01-2021 of kp act 5 r/w SANTHANPAR 32, thalakodu at 14:10 4 (2)(a) of kedo A (Idukki shaji kc si of BAILED BY 6 basil kp paili Male neriamangalam ekm suryanelli Hrs 2020 district) police POLICE Kalarikunnel veedu 23-01-2021 24/2021 U/s VANDIPERIYA 29, glanmary estate at 17:10 279 ipc146 r/w R (Idukki T. -

State of Kerala & Mahe District of UT of Puducherry In

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships - State of Kerala & Mahe District of UT of Puducherry Indian Oil Corporation proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in the State of Kerala & Mahe District of UT of Puducherry, as per following details: Minimum Dimension Finance to be Fixed fee/Minimum Bid Estimated monthly Type of Mode of Security deposit Sl. Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category (in M.)/Area of the site arranged amont sales Potential # site* Selection (Rs in lakhs) No. ( in Sq.M.)* by the Applicant (Rs. In lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Regular/Rural MS + HSD in Kls SC, SC Cc1, CC/DC/CFS Frontage Depth Area Estimated Estimated fund Draw of Lots/Bidding SC CC2,SC PH, working capital required for ST, ST CC1, ST requirement for development of CC2, ST PH, operation of infrastructure OBC, OBC Cc1, RO at RO OBC CC2, OBC PH, OPEN, OPEN CC1, OPEN CC2, OPEN PH 1 Punnumoodu Alappuzha Regular 160 SC CFS 25 25 625 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 2 Mararikulam to Thaikkal Beach on SH 66 Alappuzha Regular 130 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 3 Kavalam - Kidangara Road Alappuzha Rural 100 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 4 Angamaly Jn - Adlux International (NH - LHS) Ernakulam Regular 150 SC CFS 35 45 1575 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 5 Kunnumpuram Jn, Kakkanad to Thrikkakara Ernakulam Regular 160 SC CFS 25 25 625 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 on Kunnumpuram NGO Quarters Road 6 Fort Kochi to Mattancherry Ernakulam Regular 160 SC CFS 25 25 625 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 7 Puthencruz to Kolenchery Ernakulam Regular -

June 2018 to Engage with the Audience in Never- Before Ways

“Social media has made journalists more powerful” Even as technology has lowered entry barriers to journalism, social media has given professional journalists the power Issue No.005 June 2018 to engage with the audience in never- before ways. This, according to Shekhar Gupta, veteran journalist and Editor-in- Chief of ThePrint, a Foundation Grantee, Mainstream media does not step has made journalists more powerful. into villages, says Meera Jatav undelkhand is known for two things rural women journalists in their teams. In a – drought and caste-based violence. conversation with IPSMF, Meera Jatav airs B This region, which comprises small her views on a range of issues. Below are districts spread across the states of Uttar excerpts from that conversation in the origi- Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, is plagued by nal Hindi: socio-economic backwardness. As a result of On women in journalism four consecutive years of drought and crop Below are ex- failure, combined with fewer jobs under रोगⴂ को रगता है, कक भहहरा कैसे ऩत्रकारयता cerpts from the MGNREGS, at least half the families have कय सकती हℂ। मह सभस्मा कोई नमी नह ॊ, interview: We are members who have migrated. It accounts for चरती आ यह है। ऩय रोगⴂ की सोच ह फन गई doing With entities a little over 30% of all the caste-based vio- थी कक ऩत्रकारयता भᴂ तो ऩझ셁ष ह होते हℂ। like ThePrint lence in इसलरए much that doing stories the coun- ऩत्रकाय की is edgy that the main- try and is ऩहचान stream media far from फनाने भᴂ, and it’s does not gender- अफ भℂ सपर working… touch, how do sensitive. -

TRENDS in NEWSROOMS 2020 #2 Amplifying Women’S Voices IMPRINT

TRENDS IN NEWSROOMS 2020 #2 Amplifying Women’s Voices IMPRINT TRENDS IN NEWSROOMS 2020 #2: AMPLIFYING WOMEN’S VOICES PUBLISHED BY: WAN-IFRA Rotfeder-Ring 11 60327 Frankfurt, Germany CEO: Vincent Peyrègne COO: Thomas Jacob EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, WORLD EDITORS FORUM: Cherilyn Ireton DIRECTOR, MEDIA DEVELOPMENT & WOMEN IN NEWS PROGRAMME: Melanie Walker DIRECTOR OF INSIGHTS: Dean Roper EDITOR: Cherilyn Ireton AUTHOR: CONTRIBUTOR: Simone Flueckiger Rebecca Zausmer COVER ARTWORK/LAYOUT: Gordon Steiger, www.gordonsteiger.com 2 TRENDS IN NEWSROOMS 2020 #2: AMPLIFYING WOMEN’S VOICES Cherilyn Ireton Executive Director, About the Report World Editors Forum In between editing Post Covid-19, these processes are at risk. Not so much in the pioneering newsrooms which have and the production the capacity to entrench them as part of standard of this Trends in operating practice, but in the already-marginal operations where the loss of advertising from the Newsrooms report, printed newspaper during the Covid-19 crisis, will Covid-19 happened. push them closer to economic meltdown. Inevita- ble downsizing and survival strategies could well threaten to knock down the issue of gender on the list of newsroom priorities. At the time of writing, the disease is rampaging its way across the world, leaving societies scarred and So it is going to take the collective strength and priorities upended. The news business too. It’s too determination of all good women (and men) in early to determine the extent of the disruption, but the news business to ensure that the good work is sitting in isolation, in the midst of the crisis, it feels not undone.