'Others'-An Intersectional Analysis of Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A South Asian Movement's Social

Justpeace Prospects for Peace-building and Worldview Tolerance: A South Asian Movement’s Social Construction of Justice A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Jeremy A. Rinker Master of Arts University of Hawaii, 2001 Bachelor of Arts University of Pittsburgh, 1995 Director: Dr. Daniel Rothbart, Professor of Conflict Resolution Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Spring Semester 2009 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright: 2009 Jeremy A. Rinker All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the many named and unnamed dalits who have endured the suffering and humiliation of centuries of social ostracism, discrimination, and structural violence. Their stories, though largely unheard, provide both an inspiration and foundation for creating social justice. It is my hope that in telling and analyzing the stories of dalit friends associated with the Trailokya Bauddha Mahasangha, Sahayak Gana (TBMSG), both new perspectives and a sense of hope about the ideal of justpeace will be fostered. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all those that provided material, emotional, and spiritual support to me during the many stages of this dissertation work (from conceptualization to completion). The writing of a dissertation is a lonely process and those that suffer most during such a solitary process are invariably the writer’s family. Therefore, special thanks are in order for my wife Stephanie and son Kylor. Thank you for your devotion, understanding, and encouragement throughout what was often a very difficult process. I will always regret the many Saturday trips to the park that I missed, but I promise to make them up as best I can as I begin my new life as Dr. -

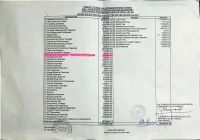

5134Payments

ПАТНАР FOUNOAT10NFOR EOUCATlON $ND TRAIN'NG OF АМОMANAGEMENT САМИ}, мупом. носн! • 683 lNCOMEАНО AccQtJNT FQR твр УЕАВ ЕНОЕО314-2020 EXPENOlTUR lNCOME То Satahesand Albwances 33197035.оо ву Тишоп Fee 131462874.23 Taxes То Ren(R3tes and 627656.ОО Ву Registration Fee 710115.00 То ТгачеШпд Expenses 555676ђ.оо Ву Hostel Fee Б159085.СО То P'.-intingand Stationery 922477.oo Ву Wscellaneous lncome 335194.00 E»enses То Advertisernent 3917809.00 Ву lnterest Receivedfrom Fixed Deposit 3007621 .oo and Telesram То Postage.Teiephone 443457.49 Ву tncome from Reprographics 5515.00 PeriQdicats То New•spapersand 227249.oo Ву Identity Card Fee 175800.00 о Suesctip)on 469706.oo Ву University Sports Atflliation Fee 89070. ОО о 0ffce Expenses 2730499.оо Ву Interest received{гот other Deposits 106409.00 То Electricity and Watet Charge± 7081001.оо Ву Aluminl Fee 160200.oo Тс Repairs апа Maintenance 9237919.оо Ву 1псота {гот Funded Projects 397595.00 То Vehide Maintenance Charges 1233350.оо Ву Certiftcation Fee 1039663.00 Charges То Conveyance 306219.оо Ву Rent Received 100000.00 То Sernhar and Соп[егелсе Expenses 23712049 То Fees and Chxses 170796550 То Interest and Валк Charges 163442.76 Ртодгатте (РОР)Exp•nsec 960997,00 То ОспаЕопала Gift 446980.оо То Ptacement Expenses 3567741.oo То GeneraI tnsurance 460715.оо То Заг<ел E»enses 3335176.оо То Hcstel E.venses 2320379.oo То S:atf WeEare Expenses 43033.оо То Expenses 29*13.00 То Hcuse keeping Expenses 274369&00 То CSSR Expeases 74190.оо То Examhaticn Expease 314406.оо То Medical Expenses То Facutty0eveiopment -

Equality: Valuing Women at the Workplace

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668 PP 70-76 www.iosrjournals.org (En)Gender(ing) Equality: Valuing Women at the Workplace Preeti Shirodkar I. INTRODUCTION The first step in the evolution of ethics is a sense of solidarity with other human beings. Albert Schweitzer The twentieth century has no doubt seen a great deal of changes, including a larger number of women entering the workplace, in varied professions and rising to positions of power. And yet, this is hardly a cause to celebrate, especially in the India context, if one were to examine the figures that expose this celebration of women power as prematurely celebratory and therefore misplaced. If at all, it can be considered as a step in the right direction, even if it is basically a very small step at that. Although we would like to believe that a large number of women are working today, an article entitled „Why Indian Women Leave the Workforce‟ published in Forbes states “women make up 24% of the workforce in India, which boasts of one of the largest working populations in the world. Only five percent of these reach the top layer, compared to a global average of 20%.” So also, according to the International Labour Organisation‟s Global Employment Trends 2013 Report, “out of the 131 countries with available data, India ranks 11th from the bottom in labour force participation.” Ironically of these it was estimated in 2009-2010 that 26.1% of these were rural workers and only 13.8% were urban workers. -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

Seven Years of Nirbhaya What Has Been Change Kumari Anupama Rai Abstract

© 2020 JETIR April 2020, Volume 7, Issue 4 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Seven Years of Nirbhaya What Has Been Change Kumari Anupama Rai Abstract In this study I have examine the rape trends and situation after NIRBHAYA CASE in India. Present study used National Crime Record (NCRB) India data. Data on crimes in India are annually published by the NCRB. Crimes reported to police station all over country and refer to report and register crime. The reasons of incidents of crime are not capture by the Bureau. NCRB gives data on the basis of police recorded crime cases are being captured. In this study I have gone through the major reason behind, effect on society and what changes can be made. Rape is the fastest growing crime in India1 as compared to other crime incidence of women. Also I have uncovered some unknown rape crime that took place in the society on the name of reputation, to the depressed class woman (economically), of the working women either private sector or government sector. Meaning of RAPE From the latin word rape is define as the rapio, it means ‘to seize’. It signifies as the ravishment against her will or without her consent, or with her consent by putting her in fear, danger. Rape is the fourth highest crime committed in India. Rape has been defined under section 375 of INDIAN PENAL CODE 18602. Not less than 7 years of punishment are awarded for rape; before the Criminal Amendment Act of 2018. Prior to 2005, there was less rape in India. -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

Supremo Amicus Volume 22 Issn 2456-9704

SUPREMO AMICUS VOLUME 22 ISSN 2456-9704 ______________________________________________________________________________ NEED FOR UNIFORM SENTENCING what exactly is Uniform Sentencing Policy? POLICY FOR RAPE Whether there is a need for uniform sentencing policy in case of rape and its By Nishi Kumari viability. From School of Legal Studies, CMRU INTRODUCTION ABSTRACT Rape is one of the most heinous offences From ancient times, human civilization has against women. It is not just a crime against been maintaining the social order in society a private individual but against the society. by developing rules and regulations which The sexually starved society has threatened are ideally followed by the people. In the case and is still threatening the very right to liberty of its breach, he/she is punished for the same of women. According to recent government in the ordinary course of justice. Earlier, the data released in September 2020, around 4, main focus of the punishment was to have a 05,861 cases of crime against women was recorded during the year, out of which 32,033 deterrent effect by giving brutal punishment. 3 However, with the human development and cases of rape were reported. social change punishment became more rational and its focus tilted towards the The statistics also reveal that about 94% of reformative approach. Despite such an the reported rapes were committed by a encouraging approach a major lacuna exists person who shared a close relationship with in the Indian Criminal Law system which the victim. It is pertinent to note that, in India, hampers the very purpose of the criminal the crime of rape is associated with the notion justice system.1 One of the major stage of a of shame, honour and grace of the family, criminal Justice System is Sentencing. -

Domestic Violence Against Women in India: a Case Study

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN INDIA: A CASE STUDY ABSTRACT OF THE /^C THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fioctor of $I)ilDs;opl)p •^ ^'^ IN (, POLITICAL SCIENCE BY RAHAT ZAMANI Under the Supervision of Dr. Rachana Kanshal DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALJGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2009 ABSTRACT Today human beings live in the so-called civilized and democratic society that is based on the principles of equality and freedom for all. It automatically results into the non-acceptance of gender discrimination in principle. Therefore, various International Human Rights norms are in place that insist on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women and advocate equal rights for women. Womens' year, women decade etc. are observed that led to the creation of mass awareness and sensitization of people about rights of women. Many steps are taken by the government in the form of various policies and programmes to promote the status of women and to realize women's rights. But despite all the efforts, the basic issue that threatens and endangers the very existence of women is the issue of domestic violence against women. John Stuart Mill put it into his book 'the subjection of women' in 1869 that, 'marriage should be thought of as a partnership of equals analogous to a business partnership and the family not a school of despotism but the real school of the virtues of freedom'. Contrary to this women who constitute about half of the world's population are the worst victim of violence and exploitation within home. -

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

Vishaka & Ors. Vs State of Rajasthan De Jure Nexus

VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 2021 ISSN: 2582-7782 DE JURE NEXUS LAW JOURNAL Author: Muskan Dadia Government Law College, Churchgate 1st Year, BLS LL.B. VISHAKA & ORS. VS STATE OF RAJASTHAN Citation Of The Case- (1997) 6 SCC 24 Name Of The Court – Honourable Supreme Court Of India Honorable Bench- Chief Justice J.S. Verma, Justice Sujata V. Manohar and Justice B.N. Kirpal. Date Of Judgement- 13th August, 1997. Facts Of The Case- Bhanwari Devi, a woman belonging from Bhateri, Rajasthan started working under the Women’s Development Project (WDP) run by the Government of Rajasthan, in the year 1985. She was employed as a ‘Saathin’ which means ‘friend’ in Hindi. In the year 1987, as a part of her job, Bhanwari took up an issue of attempted rape of a woman who hailed from a neighboring village. For this act, she gained full support from the members of her village. In the year 1992, Bhanwari took up another issue based on the government’s campaign against child marriage. This campaign was subjected to disapproval and ignorance by Dejurenexus.com VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 2021 ISSN: 2582-7782 all the members of the village, even though they were aware of the fact that child marriage is illegal. In the meantime, the family of Ram Karan Gurjar had made arrangements to perform such a marriage, of his infant daughter. Bhanwari, abiding by the work assigned to her, tried to persuade the family to not perform the marriage but all her attempts resulted in being futile. The family decided to go ahead with the marriage. -

Land Conflicts and Attacks on Dalits: a Case Study from a Village in Marathwada, India R

FIELD REPORT Land Conflicts and Attacks on Dalits: A Case Study from a Village in Marathwada, India R. Ramakumar* and Tushar Kamble† The right to own property is systematically denied to Dalits. Landlessness – encompassing a lack of access to land, inability to own land, and forced evictions – constitutes a crucial element in the subordination of Dalits. When Dalits do acquire land, elements of the right to own property – including the right to access and enjoy it – are routinely infringed (Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice 2007). In 1996, a nongovernmental organization undertook a door-to-door survey of 250 villages in the state of Gujarat and found that, in almost all villages, those who had title to land had no possession, and those who had possession had not had their land measured or faced illegal encroachments from upper castes (Human Rights Watch 1999). …the distinction and discrimination based on caste still prevails in Maharashtra. A slight provocation like a dispute at the water pump leads to polarization as Dalits and non-Dalits; non-Dalits attack Dalitbastis , destroy their houses and even kill them…The Dalits are not supposed to assert their rights and equality before the law. If they do, they have to pay a price (PUCL 2003). Landlessness is a pervasive feature of Dalit households in rural India. Landlessness is foundational to the existence of Dalits as a distinct social group in the rural areas; it forms the material basis for the domination and exploitation of Dalits in the non-economic spheres as well. The caste system thus contains elements of both social oppression and class exploitation. -

Gender Violence in India: a Prajnya Report 2020

2020 1 GENDER VIOLENCE IN INDIA 2020 A Prajnya Report This report is an information initiative of the Gender Violence Research and Information Taskforce at Prajnya. This year’s report was prepared by Kausumi Saha whose work was supported by a donation in memory of R. Rajaram. It builds on previous reports authored over the years by: Kavitha Muralidharan, Zubeda Hamid, Shalini Umachandran, S. Shakthi, Divya Bhat, Titiksha Pandit, Mitha Nandagopalan, Radhika Bhalerao, Jhuma Sen and Suchaita Tenneti. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution and support of Gynelle Alves who has designed the report cover since 2009. © The Prajnya Trust 2020 2 CONTENTS GLOSSARY ................................................................................................................................................. 3 ABOUT THIS REPORT ................................................................................................................................ 5 GENDER VIOLENCE IN INDIA: STATISTICAL TABLE .................................................................................... 6 1. THE POLITICS OF SEXUAL AND GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE AGAINST DALIT WOMEN ....................... 12 2. PRE-NATAL SEX SELECTION / FEMALE FOETICIDE .............................................................................. 18 3. CHILD MARRIAGE, EARLY MARRIAGE AND FORCED MARRIAGE ........................................................ 24 4. HUMAN TRAFFICKING .......................................................................................................................