Land Conflicts and Attacks on Dalits: a Case Study from a Village in Marathwada, India R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A South Asian Movement's Social

Justpeace Prospects for Peace-building and Worldview Tolerance: A South Asian Movement’s Social Construction of Justice A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Jeremy A. Rinker Master of Arts University of Hawaii, 2001 Bachelor of Arts University of Pittsburgh, 1995 Director: Dr. Daniel Rothbart, Professor of Conflict Resolution Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Spring Semester 2009 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright: 2009 Jeremy A. Rinker All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the many named and unnamed dalits who have endured the suffering and humiliation of centuries of social ostracism, discrimination, and structural violence. Their stories, though largely unheard, provide both an inspiration and foundation for creating social justice. It is my hope that in telling and analyzing the stories of dalit friends associated with the Trailokya Bauddha Mahasangha, Sahayak Gana (TBMSG), both new perspectives and a sense of hope about the ideal of justpeace will be fostered. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all those that provided material, emotional, and spiritual support to me during the many stages of this dissertation work (from conceptualization to completion). The writing of a dissertation is a lonely process and those that suffer most during such a solitary process are invariably the writer’s family. Therefore, special thanks are in order for my wife Stephanie and son Kylor. Thank you for your devotion, understanding, and encouragement throughout what was often a very difficult process. I will always regret the many Saturday trips to the park that I missed, but I promise to make them up as best I can as I begin my new life as Dr. -

Collegewise Result Statistics Report

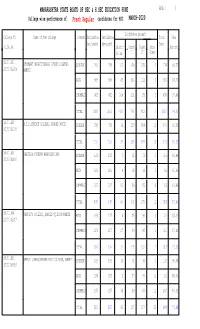

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 1 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC MARCH-2020 Candidates passed College No. Name of the collegeStream Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 58.01.001 YESHWANT MAHAVIDYALAYA JUNIOR COLLEGE, SCIENCE 789 788 109 429 235 1 774 98.22 27151702019 NANDED ARTS 368 368 63 124 122 3 312 84.78 COMMERCE 463 462 244 151 55 0 450 97.40 TOTAL 1620 1618 416 704 412 4 1536 94.93 58.01.002 N.E.S.SCIENCE COLLEGE, NANDED NANDED SCIENCE 710 710 30 255 384 10 679 95.63 27151702105 TOTAL 710 710 30 255 384 10 679 95.63 58.01.003 PRATIBHA NIKETAN MAHAVIDYALAYA SCIENCE 123 123 3 31 78 3 115 93.49 27151702405 ARTS 105 105 4 16 42 3 65 61.90 COMMERCE 207 207 53 69 55 6 183 88.40 TOTAL 435 435 60 116 175 12 363 83.44 58.01.004 PEOPLE'S COLLEGE, NANDED TQ.DIST-NANDED ARTS 183 177 4 25 90 3 122 68.92 27151702017 COMMERCE 208 207 27 90 60 4 181 87.43 TOTAL 391 384 31 115 150 7 303 78.90 58.01.005 NETAJI SUBHASCHANDRA BOSE COLLEGE, NANDED SCIENCE 150 150 10 31 92 3 136 90.66 27151703816 ARTS 234 233 2 27 99 14 142 60.94 COMMERCE 237 237 30 99 66 11 206 86.91 TOTAL 621 620 42 157 257 28 484 78.06 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 2 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC MARCH-2020 Candidates passed College No. -

Police Matters: the Everyday State and Caste Politics in South India, 1900�1975 � by Radha Kumar

PolICe atter P olice M a tte rs T he v eryday tate and aste Politics in South India, 1900–1975 • R a dha Kumar Cornell unIerIt Pre IthaCa an lonon Copyright 2021 by Cornell University The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https:creativecommons.orglicensesby-nc-nd4.0. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New ork 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 2021 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kumar, Radha, 1981 author. Title: Police matters: the everyday state and caste politics in south India, 19001975 by Radha Kumar. Description: Ithaca New ork: Cornell University Press, 2021 Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021005664 (print) LCCN 2021005665 (ebook) ISBN 9781501761065 (paperback) ISBN 9781501760860 (pdf) ISBN 9781501760877 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Police—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Law enforcement—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste— Political aspects—India—Tamil Nadu—History. Police-community relations—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste-based discrimination—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HV8249.T3 K86 2021 (print) LCC HV8249.T3 (ebook) DDC 363.20954820904—dc23 LC record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005664 LC ebook record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005665 Cover image: The Car en Route, Srivilliputtur, c. 1935. The British Library Board, Carleston Collection: Album of Snapshot Views in South India, Photo 6281 (40). -

Introduction-Caste Matters (2009) by Suraj Yengde.Pdf

From Suraj Yengde, Caste Matters (Gurgoan, India: Penguin Viking, 2009) Introduction Caste Souls: Motifs of the Twenty-first Century Taking me into her cushy arms, my aai (paternal grandmother) was reminding me of the importance of my presence in her life. ‘My dearest maajhya baalla, you are so full of life. You’ve the best eyes. You’ve so many qualities that I can barely count them.’ Her darkened face and frail skin glow in the night, the cheapest light bulb in the market—known as ‘zero-power bulb’, which truly was a lightless bulb—the only source of light in the room, was switched off. She was consoling me in the room the size of a Toyota Minibus that I shared with her, my mother, father, sister and brother. I shared the floor space underneath the cot with my sick father and brother. Perpendicular to the cot on nylon mats slept my mother and sister. Running her palm on my face in circles, Aai started massaging my head. Her soft palm had seen everything—the horrors of untouchability, the traditions of imposed inferiority, and her resolution to labour to build her family’s life by working in farms and fields as a landless labourer, a servant at someone’s house or in the mill. She represents the traditions of unknown yet so great people. The people made outcastes by the Hindu religious order, deemed despicable, polluted, unworthy of life beings whose mere sight in public would bring a cascade of violence upon the entire community. In India, casteism touches 1.35 billion people. -

Osmanabad District Maharashtra

For Official Use Only 1758/DBR/2013 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION OSMANABAD DISTRICT MAHARASHTRA By Bhushan R. Lamsoge Scientist-C - CENTRAL REGION NAGPUR 2013 OSMANABAD DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical Area : 7512 sq. km. Administrative Divisions : Taluka-8; Osmanabad, Tuljapur, (As on 31/03/2012) Omerga, Lohara, Bhoom, Kallamb, Paranda and Washi. Villages : 729 Grampanchayat : 622 Population (Census, 2011) : 16,60,311 Normal Annual Rainfall : 600 mm to 850 mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic unit : One; Balaghat Plateau Major Drainage : One; Manjra 3. LAND USE (2010-11) Forest Area : 50.53 sq. km. Net Area Sown : 6401.80 sq. km. Cultivable Area : 7229 sq. km. 4. SOIL TYPE Shallow, Medium and Medium deep soils. 5. PRINCIPAL CROPS (2010-11) Cereals : 4120 sq. km. Pulses : 2200 sq. km. Total Oil Seeds : 1310 sq. km. Sugarcane : 240 sq. km. 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (2006-07) Nos. Potential Created (ha) Dugwells : 47982 133535 Borewells : 15834 40258 Surface Flow Schemes : 3428 6238 Lift Irrigation Schemes : 4708 11682 Net Irrigated Area : 191713 7. GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS (As on 31/03/2012) Dugwells : 25 Piezometers : 2 8. GEOLOGY Upper Cretaceous-Lower Eocene : Deccan Trap Basalt 9. HYDROGEOLOGY Water Bearing Formation : Basalt- weathered/fractured/ jointed vesicular/massive, under. phreatic and semi-confined to confined conditions Premonsoon Depth to Water : 4.15 to 17.35 m bgl Level (May-2011) Postmonsoon Depth to Water : 1.2 to 7 m bgl Level (Nov.-2011) Premonsoon Water Level Trend : Rise: 0.2 to 0.55 m/year (2002-2011) Fall: Negligible to 0.3 m/year Postmonsoon Water Level Trend : Rise: 0.01 to 0.83 m/year (2001-2011) Fall: Negligible to 0.32 m/year 10. -

District Survey Report, Osmanabad

District Survey Report, Osmanabad (Draft) (2018) Mining Section-Collectorate, Osmanabad 1 PREFACE District Survey Report has been prepared for sand mining or river bed mining as per the guidelines of the Gazette of India Notification No. S.O.141 (E) New Delhi, Dated 15th January 2016 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate mentioned in Appendix-X. District Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA) and District Environment Assessment Committee (DEAC) have been constituted to scrutinize and sanction the environmental clearance for mining of minor minerals of lease area less than five hectares. The draft of District Survey Report, Osmanabad is being placed on the website of the NIC Osmanabad for inviting comments/suggestions from the general public, persons, firms and concerned entities. The last date for receipts of the comments/suggestion is twenty one day from the publication of the Report. Any correspondence in this regard may kindly be sent in MS- Office word file and should be emailed to [email protected] or may be sent by post to Member Secretary District level Expert Appraisal Committee Mining Section Collectorate Osmanabad 413 501 2 INDEX Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 4 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District 7 3. The List of Mining Leases in the District with location, area and period of validity 9 4. Details of Royalty or Revenue received in last three years 10 5. Detail of Production of Sand or Bajari or minor mineral in last three years 10 6. Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of the District 11 7. General Profile of the District 11 8. -

Arts, Science & Commercecollege, AQAR 2012-2013 Internal Quality

Arts Science & Commerce College, Naldurg AQAR 2012-13 Balaghat Education Society’s Arts, Science & CommerceCollege, Naldurg,Dist: Osmanabad. AQAR 2012-2013 Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) & Submission of Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) In Accredited Institutions (Revised in October 2013) NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL An Autonomous Institution of the University Grants Commission P. O. Box. No. 1075, Opp: NLSIU, Nagarbhavi, Bangalore - 560 072 India Page 1 Arts Science & Commerce College, Naldurg AQAR 2012-13 Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC All NAAC accredited institutions will submit an annual self-reviewed progress report to NAAC, through its IQAC. The report is to detail the tangible results achieved in key areas, specifically identified by the institutional IQAC at the beginning of the academic year. The AQAR will detail the results of the perspective plan worked out by the IQAC.(Note: The AQAR period would be the Academic Year. For example, July 1, 2012 to June 30, 2013) Part – A 1.Details of the Institution 1.1 Name of the Institution Arts, Science & Commerce College, Naldurg 1.2 Address Line 1 Naldurg, Taluka-Tuljapur, Address Line 2 Dist: Osmanabad City/Town Tuljapur, Dist: Osmanabad State MAHARASTRA Pin Code 413 602 Institution e-mail address [email protected] Contact Nos. O2471246042; 02471246106 Name of the Head of the Institution: Dr. Suhas Peshwe Tel. No. with STD Code: O2471246042; 02471246106 Mobile: +919850000511; +919422466624 Name of the IQAC Co-ordinator: Dr. Umakant Chanshetti Mobile: +919552637900; +919403488874 Page 2 Arts Science & Commerce College, Naldurg AQAR 2012-13 IQAC e-mail address: [email protected], [email protected] 1.3 NAAC Track ID(For ex. -

Democracy and Civility Workshop

Democracy against Civility? Majoritarian Politeness and Subaltern Dissent in Contemporary India (Board Room 601, 15th December 2016) The voting for Brexit in Britain and the presidential nomination and election of Donald Trump in USA signify growing solidarity on racial and ethnic lines in these western democracies. In democracies across the world, indeed, issues of class inequalities are increasingly framed along ethno-cultural identities , and India provides no postcolonial exception to this generalisation. Collective identities under democracies and high globalisation tend to privilege cultural majoritarianism, simultaneously constructing a fear of minority culture and numbers (Appadurai 2006). Such fears mobilized on cultural grounds through democratic processes could bring many projects of subaltern emancipation at loggerheads with majoritarian sensibilities. While democracy as a global project has significant achievements over the last century, present developments and past experiences also point to the universal problems of how to maintain trust and civility. Competitive politics, freedom of speech and association, and universal suffrage do not always result in an extension of civility towards marginal minorities. Democracy has always carried with it the possibility that the majority might tyrannize minorities (Mann, 2005). In India, as against the peril of ethnic cleansing, organized violence is limited to waves (Hansen 1999). While prejudices against minorities are increasingly institutionalized through democratic institutions and cultural codes, violence against minorities is dispersed. Yet such violence often constitutes critical events (Das, 1997). Prejudice is not merely a function of material inequalities, as the history of violence against Dalits, Muslims and other marginal groups in India suggests. Along with majoritarian politeness, prejudice constructs the paradox of democratic consolidation and institutionalised inequalities. -

Annual Report 2006

annual2006report 1 Contents 1. Executive summary . 3 2. IDSN background . 4 3. United Nations and other multilateral bodies . 6 UN Sub-Commission on the promotion and protection of human rights UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination UN Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women UN Special Rapporteurs 4. The European Union . 14 The European Parliament Interaction with EU institutions Recommendations to the European Union Hearing in the Committee on Development of the European Parliament 5. Role of Trans-national corporations . 19 6. Networking, coordination and campaigning . 19 Developments in caste-affected countries Dalit Solidarity Networks Documentation and Publications Research and Media 7. Organisation, administration and finance . 31 Organisation and administration Finances Perspectives 2007-2009 Annex 1: Audited financial statement 2006 . 33 Annex 2: Hague Dalit Women Declaration . 39 Annex 3: European Parliament Resolution on the situation of Dalits in India . 45 2 1. Executive summary cantly engaged in the study than have the governments of countries affected by caste discrimination. As part of its In India and other South Asian countries, people have support for the Sub-Commission experts mandated to been systematically discriminated against on the basis of conduct the study, International Dalit Solidarity Network their work and descent for centuries. Also known as (IDSN) organised, in March 2006, an international consul- untouchables, Scheduled Castes or outcastes, Dalits expe- tation with affected community representatives, UN agen- rience violence, discrimination, and social exclusion on a cies and experts. IDSN assisted the preparation of informal daily basis. Despite strong economic growth in India over visits by one of the Sub-Commission experts, Prof. -

The Khairlanji Massacre Is More Than Another Murder Story Avinash Pandey

The Khairlanji massacre is more than another murder story Avinash Pandey The recent verdict of the Bombay High Court in the Khairlanji massacre case, sentencing all the accused to life imprisonment, could have gone a long way in restoring ordinary people’s faith in India’s justice system and legal framework. The verdict could have marked a historic juncture in the life of the nation, announcing that the rule of law has been firmly established despite the inadequacies of the justice system in both crime investigation and trials. It could have ensured that Dalits and other underprivileged groups will face no discrimination, at least within the judicial system. For all of these reasons, the verdict was long awaited. Unfortunately, in its final coming, it proved highly inadequate and farcical, rightfully outraging civil society. The outrage is highly misplaced however; the failure of justice is not rooted in the commuting of the death sentence of six convicts into life terms for twenty-five years, but in seeing their behavior as mere revenge killing. Capital punishment is unacceptable in any civilized society, and it is quite painful to see some of the most genuine civil society members decrying the commuting to life terms and demanding for the death sentence to be awarded. Retributive justice is no justice, and no studies have confirmed any deterrence effect of capital punishment. Rather, statistics bear out that capital punishment is used mostly against the poorest and weakest sections of society. It is an official version of mob-lynching, with the poorest of the Indian society being the worst victims. -

Mob Lynching As Repercussions of Hate

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 16, 2020 MOB LYNCHING AS REPERCUSSIONS OF HATE 1Neha, 2Dr. Radhika Dev Varma Arora 1Postgraduate Student, LL.M., University Institute of Legal Studies Chandigarh University. 2Associate Professor, Chandigarh University (UILS). Abstract “There has been observed a high level of increase in Mob Lynching in India. However, Lynching isn't characterized under the Indian Legal System and there are no punishments regarding the same. The word lynch was observed during the American Revolution. In India lynching was first seen in the Khairlanji Massacre in the year 2006. Since the year 2017 there have been an absolute number of 8 situations where 5 cases happened as of the month of June. Lynching is a genuine wrongdoing and a culpable offense and it ought to be incorporated under different offenses given in the Indian Penal Code. There must exist several programmes with the goal to spread awareness among the individuals regarding lynching as a genuine offense and not to participate or promote the same. It is considered to be the obligation of the Government to punish those who do this wrong as a layman ought to not take the law into his hands. Mob Lynching is an unpalatable slur on our legitimate framework. It originates from the unreasonable idea of vigilantism and prompts anarchy. Such excrescence should be constraint with the help of an iron hand. As it is very well known that the law of any country is the mightiest sovereign in that civilized society. The majesty of law can't be contaminated -

Notification428.Pdf

(TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE GAZEETTE OF INDIA, EXTRAORDINARY PART II, SECTION 3, SUB- SECTION ( i) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS, FOOD AND PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION (Department of Food and Public Distribution) Order New Delhi, Dated 5th June, 2012 G.S.R 428 (E)/Ess.Com./Sugarcane-In exercise of the powers conferred by Clause 3 of Sugarcane (Control) Order, 1966 and having regard to the various factors mentioned in sub-clause (1) thereof, the Central Government, after consultation with such authorities, Bodies and Associations as are considered necessary by it to be consulted and on the basis of the ‘fair and remunerative price’ of sugarcane at Rs. 145.00 per quintal linked to a basic recovery of 9.5% sugar subject to a premium of Rs. 1.53 for every 0.1% point increase in the recovery above that level hereby fixes the price specified in column (4) of the Schedule hereto annexed as the ‘fair and remunerative price’ that shall be payable by the owners of the vacuum pan process sugar factories specified in the corresponding entry in column (3) of the said Schedule or their agents for the sugarcane delivered at the gate of the factory or any purchasing centre for the sugar year 2011-2012 ending the 30th September, 2012 subject to the rebates payable therefore under clause 2A of the said Order “Provided that where the transportation cost is borne by Sugar Mill Owners in the transportation of Sugarcane, from purchase centres to mills’ gate payment of transport rebate at the rate of 38 Paisa per quintal per kilometre shall be made subject to a maximum of rupees 7.65 per quintal for Sugarcane delivered for purchase at any purchasing Centre connected by rail or road.