Cheesemakingfor the Rest of Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cheeses of Italy Hard 2396.Pdf

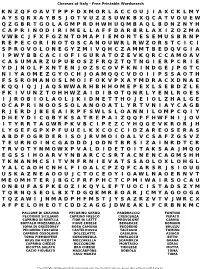

Cheeses of Italy - Free Printable Wordsearch KNZQFOAVTPPFDXMORLACC OUJIAXCKLMY AYSQRXAYBSJOTVUZZSUW KBXQCATVOUEW QZGBRTGOLAGMPRDHWHUQMBA QLBDNZNYH CAPRINODIRIMELLAFF DARBRLAXIZOZMA VWBCJFXFGZNTOMAPIEMO NTESEMUSBRNP REPECORINOTOSCANOUWRL RWZORSTCICI SPROVOLONEGYZMIVQHCZA MMTBEDQVGIA IPWYBBCACIOFIGURATO ZEVKQRCCAMOAV CASUMARZUPUBOSZFRQZTQ TNGIERPCRIE YDJNOLFXNTENJOZSCOV FKNINDGEJPGTC NIYAOMEZGYOCHJOAMQQCV DOIIPSSAOTH FSSROMANOSLMOIFOKVPXA YMDRACXDNAE KQQIQJJAQSWWARHBHHOME PEXLSEBDZLE FKIVUNZTOHHWZAIDIBO TQNRLYENLROES IJROBIOLAOLJKIDNE TTHOJEIOLZHALGE OCAPRINOOSSOLANOOATL YRTVNIAYCAGB RJERDJBEEAIRPFSWLS LOANNILOMPCQIY DHEYDICGBYKSATREPAI ZQQFFHWFNIJOV ITYRRTAGWRPKVBCIPEZ CYHQGEVKRORJH LYGEFGPXPFUUELKXCOCC IDZAREOSERAS ABDFOGRDERISOJRVMOI OALVCSAFZGSVZ TEURNOINCGADDDJODNTB RSIZAINRDTCR TRVOTYNMOWXPVALDIDETO ITAKSAAJMQO EGSSIHOARVYNBARCCSRT ACNENCAGMSHH TKNANMCSITVNFRNIEVA TSSAOLOXLOHGL YALCAOHCNHLFIOALCPZ QFCARSRJSIOUG USKAZNEAOOUJCTOCEOYI GAWLNAOERNVT MEOMHTERJBGCFRFPHCTC PMIWAIRSOCAU ONBUFASPKEOZIKQYLEF TUOCISTADSZYM TQRNQSEOLBXTDGQKMREOAR JCMYAGOOGA TQZAWIJNMADPHFMSTJYS AZRZVTVJWRCX AFPELOHEOTCDDZAGGJDW EAKLFCRBNKMC PALLONE DI GRAVINA PECORINO SARDO PADDRACCIO FONTINA PECORINO SICILIANO CAPRINO FRESCO CRESCENZA PEPATO CAPRINO DI RIMELLA FIOR DI LATTE PROVOLONE CARNIA BUFFALO MOZZARELLA PIAVE CHEESE BERGKASE ROMANO TOMA DI GRESSONEY ROSA CAMUNA PECORINO BRUZZU PECORINO TOSCANO CASTELROSSO TALEGGIO TOMINO CAPRINO OSSOLANO DOLCELATTE CASALINA ASIAGO TOMA PIEMONTESE GORGONZOLA MORLACCO BITTO BRUS DA RICOTTA MOZZARELLA SCAMORZA GRANA CAPRINO -

Le Aziende Partecipanti All'edizione 2019

Le aziende partecipanti all’edizione 2019 4 MADONNE CASEIFICIO DELL’EMILIA AIXTRA, S.C. Strada Lesignana, 130 Goikotxe, 12 - Bajo A 41123 Lesignana (MO) 01250 Araya (Araba) Tel. 059/849468 Spagna Fax 059/849468 Tel. 0034 620 911484 E-mail: [email protected] In Concorso: Idiazabal DOP Aixtra In Concorso: Parmigiano Reggiano DOP (24 Mesi) AIZPEA, E.Z. Aizpea Baserria 20212 Olaberria (Gipuzkoa) A & A FORMAGGI S.N.C. Spagna Via Casale di Sant’Angelo, 28 Tel. 0034 615 763131 00061 Anguillara Sabazia (RM) In Concorso: Idiazabal DOP Aizpea Tel. 06/99849207 E-mail: [email protected] ALAN FARM SOCIETÀ AGRICOLA In Concorso: Caciocardo; Caciotta Serafino; F.LLI ANDRIOLLO E FIGLI S.S. Ricotta Adriani; Caciolimone Via Migliara 51 Sx, 167 04014 Pontinia (LT) Tel. 0773/850147 AGASUR, S.C.A. E-mail: [email protected] C/ Limitación, 14 Web: www.caseificioalanfarm.com Polígono Industrial La Huertecilla In Concorso: Mozzarella Vaccina; Caciottone 29196 Málaga (Málaga) Morbido; Provolone Stagionato; Ricotta Spagna Vaccina Tel. 0034 952 179311 Fax 0034 952 179709 ALCHIMISTA LACTIS E-mail: [email protected] Via Sacrofano-Cassia, 4050 Web: www.quesoselpinsapo.com 00060 Sacrofano (RM) In Concorso: Queso Gran Reserva El Pinsapo Tel. 388/4678439 E-mail: [email protected] In Concorso: Stracchinato dell’Alchimista; AGRICOLTURA NUOVA S.C.S.A.I. Caciotta Gajarda; Ricotta alla Vecchia Via Valle di Perna, 315 Maniera; Ebriosus; Tufarina Veia 00128 Roma Tel. 06/5070453 ANDRE JUUSTUFARM OÜ E-mail: [email protected] Kambja Parisk, Talvikase Village Web: www.agricolturanuova.it 62028 Tartumaa In Concorso: Primo Sale; Pecorino Estonia Semistagionato; Pecorino Stagionato Extra; Tel. -

THEMATIC MENU CANTINE APERTE 2017 Saturday and Sunday € 35,00 (Matched Wine Included)

THEMATIC MENU CANTINE APERTE 2017 Saturday and Sunday € 35,00 (Matched wine included) Restaurant at the La Madonnina del Gran Paradiso Hotel : Slightly smoked Lillaz trout barley bread crouton, “vitigno friulano” reduction and salted butter Tagliatelle with truffle and asparagus tips sweet toma cheese flakes aged at “Cantina Erbavoglio” Gently cooked deer ossobuco white polenta pearls and spring side-dish Pear and Picolit cream almond sponge cake Wine by the glass of the guest region Friuli Venezia Giulia Reservation +39 0165 - 74078 THEMATIC MENU CANTINE APERTE 2017 Saturday and Sunday € 35,00 (Matched wine included) Restaurant Lou Ressignon : Farmhouse salad with tête de moine cheese and balsamic reduction Risotto with boudin Bleu d’Aoste mousse and brown bread crumbs Pig belly cooked at low temperatures with fruit mostarda sauce Whipped blueberry ice cream with strawberries flavoured with Pierrot (vendemmia tardiva Feudo San Maurizio) and sprinkle of ginger Wines by the glass of the Cooperatives“Cave des Onze Communes” and “La Crotta di Vegneron” Reservation +39 0165 - 74034 THEMATIC MENU CANTINE APERTE 2017 Saturday and Sunday € 35,00 (Matched wine included) Restaurant at the Notre Maison Hotel : Diced marinated trout with citrus fruits, yogurt and dill on a “taboulet” of Venere black rice Black maltagliati with salmon trout and pesto perlage Guinea-fowl steak with potato mousse, hazelnuts and crunchy lard Crema di Cogne flan with tegole Wines by the glass of the Cooperative “Cave Mont Blanc de Morgex” Reservation +39 0165 – 74104 -

Appetizers Salads Pizza Acquerello Risotto

APPETIZERS ACQUERELLO RISOTTO ENTREES CREAMY GEORGIA GOAT CHEESE SPREAD PERFECT TO SHARE gf RISOTTO AI FUNGHI gf PESCE warm tomato marinara, freshly baked focaccia 6. geezer farms wild mushrooms, taleggio cheese, umbria truffle pesto 25. grilled whole fish of the day, lemon, e.v. olive oil, pantelleria capers mkt. CALAMARI E CARCIOFI ARTICHOKES SMOKED SCAMORZA & gf CERNIA E CARCIOFI lightly fried rhode island calamari, baby artichokes, lemon aioli, salsa rubra 14. braised artichokes, acquerello risotto, smoked scamorza, artichoke pesto, pistacchio panure 24. pan roasted gulf grouper, baby artichokes, fingerling potatoes, add iberico pork sausage 6. supp gaeta olives in vermentino wine pacchino tomato sauce 29. POLPETTINE veal, parmesan ricotta meatballs, san marzano tomato basil sauce 14. RISOTTO ALL’ARAGOSTA SOGLIOLA & acquerello risotto, maine lobster morsels, touch of lobster bisque 29. gf POLPO IN UMIDO genuine holland dover sole, lemon caper sauce - filleted tableside mkt. braised mediterranean octopus, heirloom tomatoes, fingerling potatoes, taggiasca olives 17. CIOPPINO 5 TERRE “clay pot fisherman’s stew” of mussels, clams, scallops, snapper morsels prawn, & SPAGHETTI SQUASH EGGPLANT PARMIGIANA garlic crouton, shaved bottarga 29. provola cheese, smoked& san marzano tomato composta 14. gf POLLETTO gf COZZE PICCANTI local all natural half chicken, pepper brined pan roasted, creamer potatoes, steamed prince edward island mussels, roasted garlic, cured calabrese chiles, cerignola olives, lemon chicken jus 26. & green red little devils 17. ARTISANAL PASTA & SCALOPPINI PORCINI E PATATE GNOCCHI FONDUTA DI GORGONZOLA gf SALSICCIA - CIPOLLINI pan sauteed veal scaloppini, porcini mushrooms, golden potato, arneis wine sauce 32. house made iberico pork sausage, roasted fennel, cipolini & vine ripe tomato 14. -

Piattini Fresco Frittini Di Stagione Pasta E Secondi Le Nostre Pizze

Pachino menu-v2-Aug-v1:Layout 1 7/31/11 8:38 PM Page 1 Piattini Zucchero Bruschette Miste 7 Caprese di Cioccolato 6 Trio of bruschette; anchovies/ cherry tomatoes/ House made chocolate cake, hazelnut ice cream arugola and scamorza cheese Della giornata Tiramisu 6 Ask about today’s specials! House made tiramisu Zuppa del Giorno 8 Soup of the day Gelati e Sorbetti 5 Ice cream and sorbet Pepata di Cozze e Vongole 11 Le Nostre Pizze Affogato 6 Sautéed mussels and clams, garlic, Marinara 11 Vanilla ice cream with a shot of espresso white wine, crostini bread Tomato, garlic, anchovies Calamari Fritti 12 Margherita 12 Bevande 50 Lightly fried calamari Tomato, mozzarella, basil Sparkling Water 6. Mexican Coke 3.50 Tagliere di Salumi 14 Gricia 12 Diet Coke 3.25 Italian cured meats and cheese Pancetta, escarole, Pecorino, mozzarella, Root Beer 3.25 Italian soda 3.25 Funghi 13 Ice tea 3 Fresco Mushrooms, tomato, onions, mozzarella Espresso 2 Cappuccino 3 Insalata Tricolore 8 Fiori di Zucca 14 Mix greens salad, lemon vinagrette Squash blossom, zucchini, cherry tomatoes, Birre anchovies, mozzarella and asiago cheese Insalata alla Siciliana 11 Draft 6 Heirloom tomato salad with red onions, Pachino 15 Peroni / Pyramid Hefeweizen cucumber, pecorino cheese Cherry tomatoes, buffalo mozzarella, basil Bottles 5 Abita Light / Anderson Valley Amber Diavola 15 Moretti Frittini di Stagione Spicy Calabrese salame, arugola, tomato, chili pepper, mozzarella Bottles 6 Arancini di Carne 8 21st Amendment Watermelon Fried risotto balls with tomato and Prociutto & Burrata 15 Affligem Blonde / Flying Dog Pale Ale meat sauce Prosciutto di Parma and burrata cheese Napa Smith IPA Fiori di Zucca 8 Frutti di Mare 16 Vino al Bicchiere Fried squash blossoms, mozzarella, anchovy Clams, mussels, garlic, anchovies, tomato Wines by the glass or ½ liter carafe Schiacciata Siciliana (about three glasses). -

Menu Circolare | Circular Menu 29

MENU CIRCOLARE | CIRCULAR MENU 29 Antipasto | Starter Vitello Tonnato e Insalata Russa Primo | Main course Risotto Carnaroli al Gorgonzola DOP Dolce| Dessert Mela “al putagè” The “circularity” of this menu is linked to the “common sense” of the past domestic economy: the main ingredients are part of a single process that starts by boiling meat and vegetables together. The meat will be used for the vitello tonnato, the vegetables for the Italian Salad and the broth to cook the risotto. Every dessert needs only one apple and, of the latter, is used everything, also the peel. This menu presents a lot of peculiarity: no preservatives, no food waste and an almost energy- neutral impact in the production. Furthermore, the “circularity” allows us to keep low cost. (V) is VEGETARIAN If you have any questions about allergens, we are at your disposal PRINCIPI Acciughe al verde Anchovies, with green sauce 8 Crudo di Cocconato e Robiola d’Alba P.A.T. serviti con focaccia alla Nocciola Piemonte IGP e olio del pinerolese Cocconato ham and Robiola d’Alba (Traditional Food Products -PAT) served with hazelnut focaccia and pinerolese oil 15 Battuta al coltello, 200 g di Razza Piemontese - La Granda Raw meat, 200 g of Piedmontese Breed produced by La Granda 15 Vitello Tonnato, girello di Razza Piemontese - Consorzio Coalvi Vitello Tonnato, Veal of Piedmontese Breed produced by Coalvi Consortium with tuna sauce 15 I tipici: assaggio di antipasti Vitello Tonnato, Acciughe al verde, Insalata Russa, Peperone di Carmagnola PAT Tasting of appetizer Vitello Tonnato, -

Alma Mater Studiorum

Allma Mater Studiiorum – Uniiversiità dii Bollogna DOTTORATO DI RICERCA BIOTECNOLOGIE DEGLI ALIMENTI Ciclo XXI Settore scientifico disciplinare di afferenza: AGR/16 STUDIO DELLA MATURAZIONE DI FORMAGGI PECORINO STAGIONATI IN STABILIMENTO E IN GROTTA Presentata dalla dott.ssa: Elena Caffarri Coordinatore Dottorato Relatore Chiar.mo Prof. Chiar.ma Prof.ssa Giuseppe Losi Elisabetta Guerzoni Esame finale anno 2009 Alla mia famiglia Indice Parte introduttiva ................................................................ 1 Capitolo 1 Il formaggio ....................................................... 3 1.1 Le origini del formaggio ......................................................................... 3 1.2 Definizione e classificazione .................................................................. 5 1.3 Il formaggio Pecorino ............................................................................. 7 1.4 Tecnologia di produzione del Pecorino ................................................ 10 1.4.1 Preparazione del latte .................................................................... 11 1.4.2 Coagulazione del latte ................................................................... 12 1.4.3 Spurgo e rottura della cagliata ....................................................... 14 1.4.4 Cottura e Salatura .......................................................................... 15 1.4.5 Maturazione e Stagionatura........................................................... 15 Capitolo 2 Le G rotte di Santarcangelo .......................... -

Bites Dips Salads Flatbreads Sandwiches

Interested in taking something home with you? Ask your server what products we have available in our retail section and ways to use them. Bites Salads Cheese & Charcuterie | 20 Veggie Chopped | 13 selection of cheeses and meats, warmed bread, crackers, arugula, spinach, peppadews, kalamata artisan spreads, we olive mustards, accoutrements olives, mozzarella, bell pepper, peach Artisan Cheese | 18 balsamic pickled onions, EVOO, balsamic selection of cheeses, warmed bread, artisan spreads, Chopped | 14 we olive mustards, accoutrements veggie chopped with pepperoni Charcuterie & Mustard | 20 selection of meats, genoa salami, prosciutto, warmed bread, crackers, Seasonal Salad | 14 artisan spreads, we olive mustards, accoutrements blood orange olive oil, strawberry balsamic Artisan Bread | 3 vinegar, spinach, candied walnuts, garlic olive oil baguette, EVOO, aged balsamic heirloom tomatoes, carmody cheese Castelvetrano Olives | 7 Side | 7 green Sicilian olives basil olive oil, blackberry balsamic, carmody cheese Bowl of Almonds | 7 Caprese | 12 California almonds, EVOO heirloom tomatoes, mozzarella, basil, Stuffed Peppadews | 9 EVOO, balsamic salami, goat cheese, pickled sweet pepper, aged balsamic Crostini | 9 Flatbreads Burrata cheese, herbs, EVOO roasted tomato-black olive tapenade, Carmody cheese, EVOO Artichoke Caper | 12 Prosciutto-Wrapped Dates | 11 artichoke caper tapenade, mozzarella, roasted tomatoes, basil, meyer lemon meyer lemon olive oil goat cheese, dates olive oil crushed walnuts, blood orange balsamic Burrata & Spicy Honey -

Beverage Menu

7 Room Service Menu Beverage Menu Selection of Juices Freshly squeezed orange, grapefruit juice Glass 7 Pitcher 24 Chilled apple, cranberry, pineapple, tomato, pomegranate Glass 6 Pitcher 21 Made to order watermelon juice (seasonal) glass 7 Pitcher 24 ROOM SERVICE MENU SERVICE ROOM Veggie cocktail 8 Kale, beet, carrot, celery, cucumber, tomato Filtered Coffee (regular or decaffeinated) small pot (3 cups) 9 large pot (6 cups) 11 French coffee press 12 Cappuccino, Café Latte, Mocha 6 Espresso 5 Double Espresso 6 Harney & Sons Tea English Breakfast, Earl Grey, Ceylon, Darjeeling, Green Tea, Lemon, Assam small pot 6 large pot 8 20% gratuity and $7 delivery charge will be added to your bill Beverage Menu Harney & Sons Herbal Infusions Chamomile, Peppermint, Raspberry, Cinnamon Spice small pot 6 large pot 8 Hot or Cold Chocolate small pot 7 large pot 9 Glass of Cold or Hot Milk 4 Soy milk 4 Mineral Still Water Evian small 4 Evian large 7 Sparkling ROOM SERVICE MENU SERVICE ROOM Perrier small 4 Perrier large 7 Soft Drinks Coca-Cola, Diet Coke, Ginger Ale, Sprite, Tonic, Club Soda 4 Energy Drinks Red Bull 6 20% gratuity and $7 delivery charge will be added to your bill Beverage Menu Cocktail Old Fashioned 12 Bourbon, simple syrup, orange, angostura bitter Mojito 12 Rum, simple syrup, mint, lime, soda Margarita 14 Tequila, fresh lime juice, agave Strawberry Basil Martini 16 Vodka, puréed strawberry, fresh basil Champagne glass bottle Thienot Brut 16 120 Veuve Clicquot Brut 20 175 Thienot Rose 19 175 White Wine glass bottle ROOM SERVICE MENU SERVICE -

From July 29-August 1! Restaurants Are Pairing up W

Sacramento-area restaurants are “Celebrating the American Cheese Plate” from July 29-August 1! Restaurants are pairing up with american artisan and specialty cheesemakers for a special Sacramento Cheesemaker Dine Around while the ACS Conference & Competition is in town. Each restaurant will take a different approach to the partnership, from small tasting plates to full meals featuring american artisan and specialty cheeses. Some menus and featured items are offered only on the evening of Thursday, July 31, while others may be offered all week. Contact restaurants directly to learn more about their offerings. Please note that menus are subject to change at any time without notice. Reservations are strongly encouraged. 1800 L Street, (916) 447-9440 www.aiolibodega.com, http://www.nicasiocheese.com Please call for details. 1050 20th Street, (916) 706-2636 www.blockbutcherbar.com, http://www.roguecreamery.com Please call for details. 319 6th Street, West Sacramento (916) 372-2436 www.broderick1893.com, http://fiscalinicheese.com Featuring: Fiscalini Habanero cheddar custard with heirloom tomato salsa, cilantro gel & house made tortilla chips "Smoke em if you got em" burger: Smoked pepper crusted hamburger patty topped with Fiscalini smoked cheddar, served with smoked bacon, heirloom tomatoes & arugula on a fresh onion bun with smoked paprika aioli 1801 L Street #50 (916) 443-1010 www.capitaldime.com, http://www.redwoodhill.com Offering: Bucheret grilled cheese with granny smith apples and onion jam Smoked cheddar and cauliflower pierogi Lamb slider with aged goat cheddar and craisin harissa Eastern European ham and raw feta stuffed peppers. 1131 K Street (916) 443-3772 www.elladiningroomandbar.com, http://www.cowgirlcreamery.com Please call for details. -

CHEESE 18-21 a JOURNEYTOMOUNTAINPASTURES 2015 September Wfood.Com Br A, Italy

An event by CHEESE September 2015 Bra, Italy 18-21 am A JOURNEY TO MOUNTAIN PASTURES r og r P www.slowfood.com Official Partners The program is chock-a-block slow Friday, Cheese 2015 with delights, from dawn till well A Journey to after dusk. In fact when the sun September 18 Mountain Pastures sets, Cheese on Stage comes to life, with screenings and musical Taste Workshops performances. Cheese returns to Bra from 18 to CHB01 21 September, organized by Slow Keep updated via The Cheese Fancier Food Italy and Città di Bra, in colla- www.cheese.slowfood.com/en 4 pm – Wine Bank, Pollenzo boration with the Ministry for Agri- 20 € – Seats available: 30 cultural, Food and Forestry Policies. What exactly does a cheese affi- This year’s Cheese focuses on Useful neur do? What skills and qualifi- mountain dairy production and is cations are required to practice packed with stories of young pro- Information the trade? The affineur has to be ducers who have chosen to live 18-21 September able to select cheeses where they and work among the peaks, val- are produced, identifying the ones leys and pastures. You will meet that have a clear-cut personali- them as you venture through the Entry into Cheese is free of ty in deference to tradition and hundreds of stalls at the Cheese charge: this includes all the typicality. Once they have been Market, together with the many streets and piazzas in the old town transferred to a suitable place, he Slow Food Presidia and affineurs where the market can be found. -

June 10 WINE & TAPAS PAIRINGS PASTA SIDES $7. / Each SOUP

75 75 95 WINES 9. /gls 14. /flight TAPAS 6. /each Eggplant Lasagna, eggplant, zucchini, and spinach, ricotta, fire roasted tomato sauce 21.00 50 …suggested Apple & Sausage Ravioli, browned butter, crisped sausage, sage, apple cider drizzle 21. Silverado Oakville Bay Scallop Ceviche, Coconut Lime PASTA Sauvignon Blanc 2018 pairing… 50 June 10th Shrimp Linguini, fresh linguini, gulf shrimp, spinach, tomatoes, spicy white wine 23. 50 Beef Bolognese, fresh tagliatelle 22. Annabella Red Blend 2017 …suggested Pork Tenderloin, Pork Belly, WINE & TAPAS pairing… Rice Noodles, Chinese 5 Spice Broth PAIRINGS Beaulieu Vineyards Napa Valley …suggested Elk Tartare, Curry Mayo, Toast Points Scottish Salmon, Grilled Scottish Salmon, Haricot Vert, Roasted Red Potatoes, Tomato, Basil, & pairing… 50 Cabernet Sauvignon 2017 Garlic Beurre Blanc * 27. gf 95 Pair a glass of wine with any tapas for $14. or with a flight for $19.50 SEAFOOD Ahi Tuna, sushi rice, ginger‐cucumber salad, nori, soy wasabi vinaigrette, sesame crust * 27. Sea Bass, baby bok choy, purple rice, lemongrass buerre blanc 36. Crab Cakes, Mango & Nappa cabbage slaw, Key lime Dijon aioli, choice of side 29. Soup of the Day Mkt. 50 SOUP / Chicken Tortilla Soup, tomatoes, corn, avocado, chilies, cheese, cilantro, lime 8. gf Springer Mountain Chicken cast Iron seared chicken breast, aligot potatoes, roasted SALAD Artisan lettuce Salad, tomatoes, blue cheese crumbles, white balsamic vinaigrette 8. carrots, sauteed swiss chard, lemon‐pepper chicken demi 23.50 gf Caesar Salad, romaine, pickled shallots,