Refrigeration-Ppt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vapour Absorption Refrigeration Systems Based on Ammonia- Water Pair

Lesson 17 Vapour Absorption Refrigeration Systems Based On Ammonia- Water Pair Version 1 ME, IIT Kharagpur 1 The specific objectives of this lesson are to: 1. Introduce ammonia-water systems (Section 17.1) 2. Explain the working principle of vapour absorption refrigeration systems based on ammonia-water (Section 17.2) 3. Explain the principle of rectification column and dephlegmator (Section 17.3) 4. Present the steady flow analysis of ammonia-water systems (Section 17.4) 5. Discuss the working principle of pumpless absorption refrigeration systems (Section 17.5) 6. Discuss briefly solar energy based sorption refrigeration systems (Section 17.6) 7. Compare compression systems with absorption systems (Section 17.7) At the end of the lecture, the student should be able to: 1. Draw the schematic of a ammonia-water based vapour absorption refrigeration system and explain its working principle 2. Explain the principle of rectification column and dephlegmator using temperature-concentration diagrams 3. Carry out steady flow analysis of absorption systems based on ammonia- water 4. Explain the working principle of Platen-Munter’s system 5. List solar energy driven sorption refrigeration systems 6. Compare vapour compression systems with vapour absorption systems 17.1. Introduction Vapour absorption refrigeration system based on ammonia-water is one of the oldest refrigeration systems. As mentioned earlier, in this system ammonia is used as refrigerant and water is used as absorbent. Since the boiling point temperature difference between ammonia and water is not very high, both ammonia and water are generated from the solution in the generator. Since presence of large amount of water in refrigerant circuit is detrimental to system performance, rectification of the generated vapour is carried out using a rectification column and a dephlegmator. -

Solar Heating and Cooling & Solar Air-Conditioning Position Paper

Task 53 New Generation Solar Cooling & Heating Systems (PV or solar thermally driven systems) Solar Heating and Cooling & Solar Air-Conditioning Position Paper November 2018 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................. 3 Introduction and Relevance ................................................ 4 Status of the Technology/Industry ...................................... 5 Technical maturity and basic successful rules for design .............. 7 Energy performance for PV and Solar thermally driven systems ... 8 Economic viability and environmental benefits .............................. 9 Market status .................................................................................... 9 Potential ............................................................................. 10 Technical potential ......................................................................... 10 Costs and economics ..................................................................... 11 Market opportunities ...................................................................... 12 Current Barriers ................................................................. 12 Actions Needed .................................................................. 13 This document was prepared by Daniel Neyer1,2 and Daniel Mugnier3 with support by Alexander Thür2, Roberto Fedrizzi4 and Pedro G. Vicente Quiles5. 1 daniel neyer brainworks, Oberradin 50, 6700 Bludenz, Austria 2 University of Innsbruck, Technikerstr. 13, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria -

Chapter 8 and 9 – Energy Balances

CBE2124, Levicky Chapter 8 and 9 – Energy Balances Reference States . Recall that enthalpy and internal energy are always defined relative to a reference state (Chapter 7). When solving energy balance problems, it is therefore necessary to define a reference state for each chemical species in the energy balance (the reference state may be predefined if a tabulated set of data is used such as the steam tables). Example . Suppose water vapor at 300 oC and 5 bar is chosen as a reference state at which Hˆ is defined to be zero. Relative to this state, what is the specific enthalpy of liquid water at 75 oC and 1 bar? What is the specific internal energy of liquid water at 75 oC and 1 bar? (Use Table B. 7). Calculating changes in enthalpy and internal energy. Hˆ and Uˆ are state functions , meaning that their values only depend on the state of the system, and not on the path taken to arrive at that state. IMPORTANT : Given a state A (as characterized by a set of variables such as pressure, temperature, composition) and a state B, the change in enthalpy of the system as it passes from A to B can be calculated along any path that leads from A to B, whether or not the path is the one actually followed. Example . 18 g of liquid water freezes to 18 g of ice while the temperature is held constant at 0 oC and the pressure is held constant at 1 atm. The enthalpy change for the process is measured to be ∆ Hˆ = - 6.01 kJ. -

Ammonia As a Refrigerant

1791 Tullie Circle, NE. Atlanta, Georgia 30329-2305, USA www.ashrae.org ASHRAE Position Document on Ammonia as a Refrigerant Approved by ASHRAE Board of Directors February 1, 2017 Expires February 1, 2020 ASHRAE S H A P I N G T O M O R R O W ’ S B U I L T E N V I R O N M E N T T O D A Y © 2017 ASHRAE (www.ashrae.org). For personal use only. Additional reproduction, distribution, or transmission in either print or digital form is not permitted without ASHRAE’s prior written permission. COMMITTEE ROSTER The ASHRAE Position Document on “Ammonia as a Refrigerant” was developed by the Society’s Refrigeration Committee. Position Document Committee formed on January 8, 2016 with Dave Rule as its chair. Dave Rule, Chair Georgi Kazachki IIAR Dayton Phoenix Group Alexandria, VA, USA Dayton, OH, USA Ray Cole Richard Royal Axiom Engineers, Inc. Walmart Monterey, CA, USA Bentonville, Arkansas, USA Dan Dettmers Greg Scrivener IRC, University of Wisconsin Cold Dynamics Madison, WI, USA Meadow Lake, SK, Canada Derek Hamilton Azane Inc. San Francisco, CA, USA Other contributors: M. Kent Anderson Caleb Nelson Consultant Azane, Inc. Bethesda, MD, USA Missoula, MT, USA Cognizant Committees The chairperson of Refrigerant Committee also served as ex-officio members: Karim Amrane REF Committee AHRI Bethesda, MD, USA i © 2017 ASHRAE (www.ashrae.org). For personal use only. Additional reproduction, distribution, or transmission in either print or digital form is not permitted without ASHRAE’s prior written permission. HISTORY of REVISION / REAFFIRMATION / WITHDRAWAL -

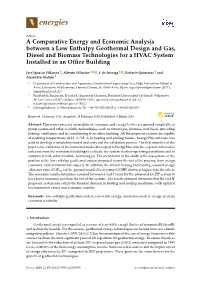

A Comparative Energy and Economic Analysis Between a Low Enthalpy Geothermal Design and Gas, Diesel and Biomass Technologies for a HVAC System Installed in an Office Building

energies Article A Comparative Energy and Economic Analysis between a Low Enthalpy Geothermal Design and Gas, Diesel and Biomass Technologies for a HVAC System Installed in an Office Building José Ignacio Villarino 1, Alberto Villarino 1,* , I. de Arteaga 2 , Roberto Quinteros 2 and Alejandro Alañón 1 1 Department of Construction and Agronomy, Construction Engineering Area, High Polytechnic School of Ávila, University of Salamanca, Hornos Caleros, 50, 05003 Ávila, Spain; [email protected] (J.I.V.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Facultad de Ingeniería, Escuela de Ingeniería Mecánica, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Av. Los Carrera 01567, Quilpué 2430000, Chile; [email protected] (I.d.A.); [email protected] (R.Q.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-920-353-500; Fax: +34-920-353-501 Received: 3 January 2019; Accepted: 25 February 2019; Published: 6 March 2019 Abstract: This paper presents an analysis of economic and energy between a ground-coupled heat pump system and other available technologies, such as natural gas, biomass, and diesel, providing heating, ventilation, and air conditioning to an office building. All the proposed systems are capable of reaching temperatures of 22 ◦C/25 ◦C in heating and cooling modes. EnergyPlus software was used to develop a simulation model and carry out the validation process. The first objective of the paper is the validation of the numerical model developed in EnergyPlus with the experimental results collected from the monitored building to evaluate the system in other operating conditions and to compare it with other available technologies. The second aim of the study is the assessment of the position of the low enthalpy geothermal system proposed versus the rest of the systems, from energy, economic, and environmental aspects. -

A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Energy Storage

sustainability Review A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Energy Storage Ioan Sarbu * ID and Calin Sebarchievici Department of Building Services Engineering, Polytechnic University of Timisoara, Piata Victoriei, No. 2A, 300006 Timisoara, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +40-256-403-991; Fax: +40-256-403-987 Received: 7 December 2017; Accepted: 10 January 2018; Published: 14 January 2018 Abstract: Thermal energy storage (TES) is a technology that stocks thermal energy by heating or cooling a storage medium so that the stored energy can be used at a later time for heating and cooling applications and power generation. TES systems are used particularly in buildings and in industrial processes. This paper is focused on TES technologies that provide a way of valorizing solar heat and reducing the energy demand of buildings. The principles of several energy storage methods and calculation of storage capacities are described. Sensible heat storage technologies, including water tank, underground, and packed-bed storage methods, are briefly reviewed. Additionally, latent-heat storage systems associated with phase-change materials for use in solar heating/cooling of buildings, solar water heating, heat-pump systems, and concentrating solar power plants as well as thermo-chemical storage are discussed. Finally, cool thermal energy storage is also briefly reviewed and outstanding information on the performance and costs of TES systems are included. Keywords: storage system; phase-change materials; chemical storage; cold storage; performance 1. Introduction Recent projections predict that the primary energy consumption will rise by 48% in 2040 [1]. On the other hand, the depletion of fossil resources in addition to their negative impact on the environment has accelerated the shift toward sustainable energy sources. -

The Potential and Challenges of Solar Boosted Heat Pumps for Domestic Hot Water Heating

Solar Calorimetry Laboratory The Potential and Challenges of Solar Boosted Heat Pumps for Domestic Hot Water Heating Stephen Harrison Ph.D., P. Eng., Solar Calorimetry Laboratory, Dept. of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada Solar Calorimetry Laboratory Background • As many groups try to improve energy efficiency in residences, hot water heating loads remain a significant energy demand. • Even in heating-dominated climates, energy use for hot water production represents ~ 20% of a building’s annual energy consumption. • Many jurisdictions are imposing, or considering regulations, specifying higher hot water heating efficiencies. – New EU requirements will effectively require the use of either heat pumps or solar heating systems for domestic hot water production – In the USA, for storage systems above (i.e., 208 L) capacity, similar regulations currently apply Canadian residential sector energy consumption (Source: CBEEDAC) Solar Calorimetry Laboratory Solar and HP water heaters • Both solar-thermal and air-source heat pumps can achieve efficiencies above 100% based on their primary energy consumption. • Both technologies are well developed, but have limitations in many climatic regions. • In particular, colder ambient temperatures lower the performance of these units making them less attractive than alternative, more conventional, water heating approaches. Solar Collector • Another drawback relates to the requirement to have an auxiliary heat source to supplement the solar or heat pump unit, -

(Vocs) in Asian and North American Pollution Plumes During INTEX-B: Identification of Specific Chinese Air Mass Tracers

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 5371–5388, 2009 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/9/5371/2009/ Atmospheric © Author(s) 2009. This work is distributed under Chemistry the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. and Physics Characterization of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in Asian and north American pollution plumes during INTEX-B: identification of specific Chinese air mass tracers B. Barletta1, S. Meinardi1, I. J. Simpson1, E. L. Atlas2, A. J. Beyersdorf3, A. K. Baker4, N. J. Blake1, M. Yang1, J. R. Midyett1, B. J. Novak1, R. J. McKeachie1, H. E. Fuelberg5, G. W. Sachse3, M. A. Avery3, T. Campos6, A. J. Weinheimer6, F. S. Rowland1, and D. R. Blake1 1University of California, Irvine, 531 Rowland Hall, Irvine 92697 CA, USA 2University of Miami, RSMAS/MAC, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, 33149 FL, USA 3NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, 23681 VA, USA 4Max Plank Institute, Atmospheric Chemistry Dept., Johannes-Joachim-Becherweg 27, 55128 Mainz, Germany 5Florida State University, Department of Meteorology, Tallahassee Florida 32306-4520, USA 6NCAR, 1850 Table Mesa Drive, Boulder, 80305 CO, USA Received: 9 March 2009 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 24 March 2009 Revised: 16 June 2009 – Accepted: 17 June 2009 – Published: 30 July 2009 Abstract. We present results from the Intercontinental 1 Introduction Chemical Transport Experiment – Phase B (INTEX-B) air- craft mission conducted in spring 2006. By analyzing the The Intercontinental Chemical Transport Experiment – mixing ratios of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) mea- Phase B (INTEX-B) aircraft experiment was conducted in sured during the second part of the field campaign, to- the spring of 2006. Its broad objective was to understand gether with kinematic back trajectories, we were able to the behavior of trace gases and aerosols on transcontinental identify five plumes originating from China, four plumes and intercontinental scales, and their impact on air quality from other Asian regions, and three plumes from the United and climate (an overview of the INTEX-B campaign can be States. -

Investigating Absorption Refrigerator Fires (Part I)

Orion P. Keifer Peter D. Layson Charles A. Wensley Investigating Absorption Refrigerator Fires (Part I) ATLANTIC BEACH, FLORIDA—In today’s recreational vehicles (RV), the then expels it when perco- most common refrigerator uses absorption refrigeration technology, lated in the boiler. It is this primarily because this type of system can operate on multiple sources action of the water which of power, including propane when electrical power is unavailable. makes the ammonia flow. These refrigerators have been under intense scrutiny in recent years The hydrogen in the re- due to numerous reported fires, apparently starting in the area of the frigeration coil maintains absorption refrigerator. Both the Dometic Corporation and Norcold a positive pressure of ap- Incorporated, two manufacturers of RV refrigerators, have been re- proximately 300-375 PSI quired by the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (2.07-2.59 MPa) when (NHTSA) to recall certain models of refrigerators which have been not in operation and, due identified as capable of failing in a fire mode. In summary, the three to its low partial pressure, NHTSA recalls indicate a fatigue crack may develop in the boiler tube promotes the evaporation of the cooling unit which may release sufficient pressurized flammable of the liquid ammonia. It coolant solution into an area where an ignition source is present. The should be noted that unlike NHTSA Recall Campaign ID Numbers are 06E076000 for Dometic conventional refrigeration (926,877 affected units), and 02E019000 (28,144 affected units) and systems which extensively 02E045000 (8,419 affected units) for Norcold. use copper due to its high thermal conductivity, the Applications Engineering Group, Inc. -

Solar Air-Conditioning and Refrigeration - Achievements and Challenges

Solar air-conditioning and refrigeration - achievements and challenges Hans-Martin Henning Fraunhofer-Institut für Solare Energiesysteme ISE, Freiburg/Germany EuroSun 2010 September 28 – October 2, 2010 Graz - AUSTRIA © Fraunhofer ISE Outline Components and systems Achievements Solar thermal versus PV? Challenges and conclusion © Fraunhofer ISE Components and systems Achievements Solar thermal versus PV? Challenges and conclusion © Fraunhofer ISE Overall approach to energy efficient buildings Assure indoor comfort with a minimum energy demand 1. Reduction of energy demand Building envelope; ventilation 2. Use of heat sinks (sources) in Ground; outside air (T, x) the environment directly or indirectly; storage mass 3. Efficient conversion chains HVAC; combined heat, (minimize exergy losses) (cooling) & power (CH(C)P); networks; auxiliary energy 4. (Fractional) covering of the Solar thermal; PV; (biomass) remaining demand using renewable energies © Fraunhofer ISE Solar thermal cooling - basic principle Basic systems categories Closed cycles (chillers): chilled water Open sorption cycles: direct treatment of fresh air (temperature, humidity) © Fraunhofer ISE Open cycles – desiccant air handling units Solid sorption Liquid sorption Desiccant wheels Packed bed Coated heat exchangers Plate heat exchanger Silica gel or LiCl-matrix, future zeolite LiCl-solution: Thermochemical storage possible ECOS (Fraunhofer ISE) in TASK 38 © Fraunhofer ISE Closed cycles – water chillers or ice production Liquid sorption: Ammonia-water or Water-LiBr (single-effect or double-effect) Solid sorption: silica gel – water, zeolite-water Ejector systems Thermo-mechanical systems Turbo Expander/Compressor AC-Sun, Denmark in TASK 38 © Fraunhofer ISE System overview Driving Collector type System type temperature Low Open cycle: direct air treatment (60-90°C) Closed cycle: high temperature cooling system (e.g. -

Clean Coil Program

TM CLEAN COIL PROGRAM There are many good reasons to clean coils! And, here is what the Nu-Calgon Clean Coil & IAQ Assurance Program can do for you... Gain significant savings on energy costs. Maintain peak operating efficiency. Enhance the cooling system’s reliability and service life. Prevent costly breakdowns. Improve Indoor Air Quality (IAQ). Backed by Nu-Calgon, the leader in HVAC and Refrigeration maintenance chemicals for more than 60 years. www.nucalgon.com l www.coilcleaning.com l www.coilprotection.com NU-CALGON CLEAN COIL & IAQ ASSURANCE PROGRAM FOR AIR CONDITIONING, REFRIGERATION SYSTEMS Over the last 50 years, Nu-Calgon has developed products that have proven themselves in the successful cleaning and protection of air conditioning and refrigeration equipment. Now, these products have been further developed into a program that will keep this equipment operating efficiently and effectively, thereby cutting electric bills, increasing the equipment’s service life, and improving the comfort and Indoor Air Quality of the building or home. An air conditioning or refrigeration system has two “finned” coils, and typically they are constructed of copper tube and aluminum fins. The evaporator coil is the indoor coil, usually referred to as the “A” coil in residential systems. It could be described as “cold” as it provides indoor cooling by absorbing the heat as a fan passes the building air over it. The condenser coil or outdoor coil is the coil that is “warm” as it rejects the heat as a fan blows outdoor air across it. These coils are sized to match the Btu cooling load or requirement of the home or building, and they are engineered for maximum heat transfer . -

Cryogenicscryogenics Forfor Particleparticle Acceleratorsaccelerators Ph

CryogenicsCryogenics forfor particleparticle acceleratorsaccelerators Ph. Lebrun CAS Course in General Accelerator Physics Divonne-les-Bains, 23-27 February 2009 Contents • Low temperatures and liquefied gases • Cryogenics in accelerators • Properties of fluids • Heat transfer & thermal insulation • Cryogenic distribution & cooling schemes • Refrigeration & liquefaction Contents • Low temperatures and liquefied gases ••• CryogenicsCryogenicsCryogenics ininin acceleratorsacceleratorsaccelerators ••• PropertiesPropertiesProperties ofofof fluidsfluidsfluids ••• HeatHeatHeat transfertransfertransfer &&& thermalthermalthermal insulationinsulationinsulation ••• CryogenicCryogenicCryogenic distributiondistributiondistribution &&& coolingcoolingcooling schemesschemesschemes ••• RefrigerationRefrigerationRefrigeration &&& liquefactionliquefactionliquefaction • cryogenics, that branch of physics which deals with the production of very low temperatures and their effects on matter Oxford English Dictionary 2nd edition, Oxford University Press (1989) • cryogenics, the science and technology of temperatures below 120 K New International Dictionary of Refrigeration 3rd edition, IIF-IIR Paris (1975) Characteristic temperatures of cryogens Triple point Normal boiling Critical Cryogen [K] point [K] point [K] Methane 90.7 111.6 190.5 Oxygen 54.4 90.2 154.6 Argon 83.8 87.3 150.9 Nitrogen 63.1 77.3 126.2 Neon 24.6 27.1 44.4 Hydrogen 13.8 20.4 33.2 Helium 2.2 (*) 4.2 5.2 (*): λ Point Densification, liquefaction & separation of gases LNG Rocket fuels LIN & LOX 130 000 m3 LNG carrier with double hull Ariane 5 25 t LHY, 130 t LOX Air separation by cryogenic distillation Up to 4500 t/day LOX What is a low temperature? • The entropy of a thermodynamical system in a macrostate corresponding to a multiplicity W of microstates is S = kB ln W • Adding reversibly heat dQ to the system results in a change of its entropy dS with a proportionality factor T T = dQ/dS ⇒ high temperature: heating produces small entropy change ⇒ low temperature: heating produces large entropy change L.