Monograph 12 Popular Culture and the Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn Unity3d Programming with Unityscript Suvak Also Available: ONLINE

Learn Unity3D Programming with UnityScript TECHNOLOGy iN ACtiON™ earn Unity Programming with UnityScript is your step-by-step Also available: Lguide to learning to make your first Unity games using UnityScript. Learn You will move from point-and-click components to fully customized features. You need no prior programming knowledge or any experience with other design tools such as PhotoShop or Illustrator - Unity3D Learn you can start from scratch making Unity games with what you’ll learn Unity3D in this book. Through hands-on examples of common game patterns, you’ll learn and apply the basics of game logic and design. You will gradually become comfortable with UnityScript syntax, at each point having everything explained to you clearly and concisely. Many beginner Programming Programming programming books refer to documentation that is too technically abstract for a beginner to use - Learn Unity Programming with UnityScript will teach you how to read and utilize those resources to hone your skills, and rapidly increase your knowledge in Unity game development. with UnityScript You’ll learn about animation, sound, physics, how to handle user interaction and so much more. Janine Suvak has won awards for her game development and is ready to show you how to start your journey as a game developer. The Unity3D game engine is flexible, Unity’s JavaScript for Beginners cross-platform, and a great place to start your game development with adventure, and UnityScript was made for it - so get started game programming with this book today. UnityScript CREATE EXcITING UNITY3D GAMES WITH UNITYScRIPT Suvak ISBN 978-1-4302-6586-3 54499 Shelve in Macintosh/General User level: Beginning 9781430 265863 SOURCE CODE ONLINE www.apress.com Janine Suvak For your convenience Apress has placed some of the front matter material after the index. -

The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot |

1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com EMAIL/USERNAME PASS (FORGOT?) Email Password NEW USER? LOGIN MUSIC DEC 02, 2009, 06:07AM Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot Matt Poland [/authors/Matt%20Poland] Straight from the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina. The following audio was included in this article: The following audio was included in this article: A few years after American indie folk’s middecade spike in visibility, which, with overexposed albums including Devendra Banhart’s Rejoicing in the Hands and Joanna Newsom’s Ys, may not have been a musical zenith, the http://www.splicetoday.com/music/live-review-the-low-anthem-and-blind-pilot 1/6 1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com genre has settled back into an unassuming position that seems to fit the music better. The “freak folk” fringe having largely faded, the nourishing, elemental influence of Americana in all its permutations continues to generate quietly exciting new music. This was evident last week at Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina, during an evening of itinerant, wornin, unbeaten songs performed by The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot. Both bands make music that is melancholy but not maudlin, that is steeped in oldtime American music but not anachronistic. The Low Anthem, a Rhode Island trio, began their set with pretty unconventional instrumentation: Ben Knox Miller playing acoustic guitar and singing, Jeffrey Prystowsky on organ, and Jocie Adams playing the crotales— sort of a small xylophone made up of discs instead of planks—with a violin bow, by far the most interesting thing I’ve seen done with a violin bow since I last saw Sigur Rós. -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

Historic Coast Culture's Farm‐To‐Fork Chef Series

Historic Coast Culture’s Farm‐to‐Fork Chef Series Presented by the St. Johns Cultural Council Overview Food is a major part of understanding any culture or region. On Florida’s Historic Coast, the culinary scene reflects 450 years of its coastal location and diverse heritage. From the original Spanish settlers, British colonists and the Greeks and Minorcans who emigrated here, visitors can savor a fascinating array of local culinary tastes and farm‐to‐table dishes. Visitors can experience everything from fine dining and quick eats to food festivals, in‐town and farm‐tasting events and culinary classes. Vision Today, farm‐to‐table Culinary is one of Florida’s Historic Coast’s key cultural assets that offers cultural travelers even deeper experiences while they are visiting. To showcase St. Johns County’s farm‐to‐table restaurants and farms, the St. Johns Cultural Council is creating a series of Farm‐to‐Fork Chef Dinners. Each will feature a top local chef from a farm‐to‐table restaurant and a local farm(s). The Chef Series will include both “In‐Town Dinners” at unusual places and “Farm Dinners” in rural settings. These culinary events will also feature local artisans, farm‐to‐table produce, local seafood and/or meats, farm‐to‐table desserts as well as local spirits. Each event will be unique, with a theme chosen by the Chef(s) for the location. These tastings will feel like an intimate dining experience where 30‐40 guests can speak one‐on‐one with the Chef(s) as well as local artisans and farms. -

TIGER M Follow Me Hyperlink Journals | TIGER M December 2013

TIGER M Follow Me Hyperlink Journals | TIGER M December 2013 Page 2 TIGER M Follow Me Hyperlink Journals | TIGER M December 2013 Brought To You By: A Warm & Humble Welcome: Update From The Physical To The Digital! Final Month of The Year! =) THIRD Hyperlink Journals Series ^_^ Hey everybody! =D And an early “Happy New Year’s Day” 2014! ^_^ Merry Holiday Season! =) Simply to keep You in tune with how the “TIGERM Follow Me Hyperlink Journals” are going to continue to be done simply a reminder that the original “Official Release” of this series was completed in October. So, the addresses Journalized for “October 2013” (First Journal) actually list “September 2013” hyperlinks. The month each Journal is released, it covers the month before it. Certainly hope that makes sense! ^_^ The links this “TIGERM Follow Me Hyperlink Journals” series covers are links I visited “November 2013.” However, the month this Hyperlink Journal was printed to be published is this month: “December 2013.” As awesome as it would be if it could be done in this day and age… it is not possible just yet for me or anyone who I know—to “travel into the future” (at this time ^_^) and collect hyperlinks for the month “December 2013” prior to me “Surfing the pixels of cyberspace” in well… “December 2013…” ^^; So long tale told – long description short— Every “TIGERM Follow Me Hyperlink Journal” covers all links visited the month prior to it. Simply restating what was just stated so hopefully clarity is true and sense is keen. There is actually a “Journal Series” that I am printing but is not yet ready for public release—an extension of the “TIGERM Follow Me Hyperlink Journals” that I’ll talk about later on in the future World Willing. -

2015 Year in Review

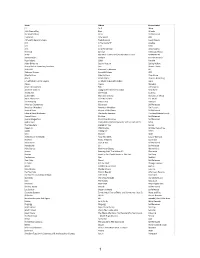

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Images of Aggression and Substance Abuse in Music Videos : a Content Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis Monica M. Escobedo San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Escobedo, Monica M., "Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis" (2009). Master's Theses. 3654. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.qtjr-frz7 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OF AGGRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE IN MUSIC VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Monica M. Escobedo May 2009 UMI Number: 1470983 Copyright 2009 by Escobedo, Monica M. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Representations of Women in Music Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1999 Creativity Or Collusion?: Representations of Women in Music Videos Jan E. Urbina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Urbina, Jan E., "Creativity Or Collusion?: Representations of Women in Music Videos" (1999). Master's Theses. 4125. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4125 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATIVITYOR COLLUSION?: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN INMUSIC VIDEOS by Jan E. Urbina A Thesis Submittedto the Facuhy of The GraduateCollege in partial folfitlment of the requirementsfor the Degree of Master of Arts Departmentof Sociology WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1999 Copyright by Jan E. Urbina 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are certain individuals that touch our lives in profound and oftentimes unexpected ways. When we meet them we feel privileged because they positively impact our lives and help shape our futures, whether they know it or not. These individuals stand out as exceptional in our hearts and in our memories because they inspire us to aim high. They support our dreams and goals and guide us toward achieving them They possess characteristics we admire, respect, cherish, and seekto emulate. These individuals are our mentors, our role models. Therefore, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to the outstanding members ofmy committee, Dr. -

The Decemberists's the Tain

November 2, 2015 American Folk Rock Cattle Raid: The Decemberists’s The Tain Kendra Leonard (Humble, TX) The Decemberists’s The Tain is a five-part, 18-minute audiovisual piece in which the music and lyrics obliquely comment on the story, crafted in stop-motion animation using paper silhouettes. In this confluence of music and literature, we hear and see an ancient Irish epic become a twentieth-century folk rock narrative. The combination of roots music with an edge and sly, knowing lyrics—together with the animation—offers an imaginative approach to the legend, the action of which is said to have taken place in the first century CE. The Decemberists’s The Tain. It’s worth the whole 18 minutes, I promise. In the original Irish legend—Táin Bó Cúailnge (pronounced “Tane bo coo-lenje”) or The Cattle Raid of Cooley—Queen Medb of Connacht plots to steal the prize bull of Ulster, the neighboring kingdom. But the bull is protected by the great Irish hero Cúchulainn, who has a number of supernatural friends who mostly help him in his quest to save the bull and, ultimately, Ulster. The battles of the Raid generally involve Cúchulainn (“coo hull-an”) against a single foe, but at times he must take on an entire army by himself, as the other warriors of Ulster are cursed and suffer a debilitating illness. The story of the Raid is one of the oldest in Irish literature and has been translated into English several times. In The Decemberists’s video, the artists include a simplified version of the story using intertitles—a technique from silent film where frames of text help viewers understand the action sequences. -

THE WRITE CHOICE by Spencer Rupert a Thesis Presented to The

THE WRITE CHOICE By Spencer Rupert A thesis presented to the Independent Studies Program of the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirements for the degree Bachelor of Independent Studies (BIS) Waterloo, Canada 2009 1 Table of Contents 1 Abstract...................................................................................................................................................7 2 Summary.................................................................................................................................................8 3 Introduction.............................................................................................................................................9 4 Writing the Story...................................................................................................................................11 4.1 Movies...........................................................................................................................................11 4.1.1 Writing...................................................................................................................................11 4.1.1.1 In the Beginning.............................................................................................................11 4.1.1.2 Structuring the Story......................................................................................................12 4.1.1.3 The Board.......................................................................................................................15 -

“The Beatles Raise the Bar-Yet Again”By Christopher Parker

“The Beatles Raise the Bar-Yet Again” by Christopher Parker I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, Parker, everyone knows that 1967’s Sgt. Pepper‘s Lonely Hearts Club Band is the Beatles’ greatest album and in fact the greatest album of all time. Nope. No way. I beg to differ. In my humble opinion, 1966’s Revolver, the Beatles album released the year before Sgt. Pepper, is the greatest. Why, you ask? In many ways, Revolver was the beginning of a new era, not only in the career of the Beatles, but in the ever-changing world of rock & roll. The world’s greatest rock band was beginning to tire of the endless touring amidst the chaos of Beatlemania. The constant battling against hordes of screaming fans, and a life lived being jostled and shoved from one hotel room to another were becoming more than tiresome. In addition, during a concert, the volume of screams often exceeded 120 decibels-approximately the same noise level as one would be exposed to if he were standing beside a Boeing 747 during takeoff. No one was listening to their music, and consequently, they were beginning to feel like, as John Lennon would later say, ‘waxworks’ or ‘performing fleas.’ Revolver signals a change from the ‘She Loves You’ era-relatively simple songs of love and relationships- to a new era of songs designed to be listened to. These were songs that could never be played at a live concert. They were creations-works of art-songs that were created to be appreciated and discussed-not to elicit screams from teenage girls. -

A Conversation with Laura Veirs by Frank Goodman (12/2005, Puremusic.Com)

A Conversation with Laura Veirs by Frank Goodman (12/2005, Puremusic.com) What was it that made it clear just a line or two into Carbon Glacier that this was something really good? It was original, first of all, both the guitar part and the melody. And it was strong, clear, very sure-footed. It was not pretentious, precious, or clever. It was recorded very well. Such were the first impressions, estimations that have only improved with time. And that wasn't even the latest album, Year of Meteors, so after a few songs, we were led there. The diversity was very satisfying, yet the continuity strong. Sounded like a young artist who really had a sense of her evolving self. There was a very free spirit to the tracking and the arrangements, a really good atmosphere. There is a palpable feeling of harmony. That was a relief, since an interview was already booked. It's still a blessed shock, every time an artist that's new to us goes into the player and a beautiful sound comes out of the speakers. And we're still very grateful when that happens. Laura Veirs is a product of the Seattle music community. She is a friend of many musical luminaries of that area, like Bill Frisell, Robin Holcomb, Wayne Horvitz, Danny Barnes, Keith Lowe and many others. She is one of the rare songwriters ever signed to Nonesuch Records. She appears to have come up through the folk channel years ago, very gracefully and convincingly into a more pop sound. This is well-illustrated by a great noisy guitar solo on "Rialto" on the new record, where the melody, handclaps and other friendly sounds keep it anchored in a very beautiful sonic bed.