PDF (Enjoying the Nightlife in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

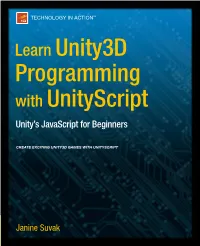

Learn Unity3d Programming with Unityscript Suvak Also Available: ONLINE

Learn Unity3D Programming with UnityScript TECHNOLOGy iN ACtiON™ earn Unity Programming with UnityScript is your step-by-step Also available: Lguide to learning to make your first Unity games using UnityScript. Learn You will move from point-and-click components to fully customized features. You need no prior programming knowledge or any experience with other design tools such as PhotoShop or Illustrator - Unity3D Learn you can start from scratch making Unity games with what you’ll learn Unity3D in this book. Through hands-on examples of common game patterns, you’ll learn and apply the basics of game logic and design. You will gradually become comfortable with UnityScript syntax, at each point having everything explained to you clearly and concisely. Many beginner Programming Programming programming books refer to documentation that is too technically abstract for a beginner to use - Learn Unity Programming with UnityScript will teach you how to read and utilize those resources to hone your skills, and rapidly increase your knowledge in Unity game development. with UnityScript You’ll learn about animation, sound, physics, how to handle user interaction and so much more. Janine Suvak has won awards for her game development and is ready to show you how to start your journey as a game developer. The Unity3D game engine is flexible, Unity’s JavaScript for Beginners cross-platform, and a great place to start your game development with adventure, and UnityScript was made for it - so get started game programming with this book today. UnityScript CREATE EXcITING UNITY3D GAMES WITH UNITYScRIPT Suvak ISBN 978-1-4302-6586-3 54499 Shelve in Macintosh/General User level: Beginning 9781430 265863 SOURCE CODE ONLINE www.apress.com Janine Suvak For your convenience Apress has placed some of the front matter material after the index. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Images of Aggression and Substance Abuse in Music Videos : a Content Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis Monica M. Escobedo San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Escobedo, Monica M., "Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis" (2009). Master's Theses. 3654. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.qtjr-frz7 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OF AGGRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE IN MUSIC VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Monica M. Escobedo May 2009 UMI Number: 1470983 Copyright 2009 by Escobedo, Monica M. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Representations of Women in Music Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1999 Creativity Or Collusion?: Representations of Women in Music Videos Jan E. Urbina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Urbina, Jan E., "Creativity Or Collusion?: Representations of Women in Music Videos" (1999). Master's Theses. 4125. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4125 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATIVITYOR COLLUSION?: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN INMUSIC VIDEOS by Jan E. Urbina A Thesis Submittedto the Facuhy of The GraduateCollege in partial folfitlment of the requirementsfor the Degree of Master of Arts Departmentof Sociology WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1999 Copyright by Jan E. Urbina 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are certain individuals that touch our lives in profound and oftentimes unexpected ways. When we meet them we feel privileged because they positively impact our lives and help shape our futures, whether they know it or not. These individuals stand out as exceptional in our hearts and in our memories because they inspire us to aim high. They support our dreams and goals and guide us toward achieving them They possess characteristics we admire, respect, cherish, and seekto emulate. These individuals are our mentors, our role models. Therefore, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to the outstanding members ofmy committee, Dr. -

THE WRITE CHOICE by Spencer Rupert a Thesis Presented to The

THE WRITE CHOICE By Spencer Rupert A thesis presented to the Independent Studies Program of the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirements for the degree Bachelor of Independent Studies (BIS) Waterloo, Canada 2009 1 Table of Contents 1 Abstract...................................................................................................................................................7 2 Summary.................................................................................................................................................8 3 Introduction.............................................................................................................................................9 4 Writing the Story...................................................................................................................................11 4.1 Movies...........................................................................................................................................11 4.1.1 Writing...................................................................................................................................11 4.1.1.1 In the Beginning.............................................................................................................11 4.1.1.2 Structuring the Story......................................................................................................12 4.1.1.3 The Board.......................................................................................................................15 -

“The Beatles Raise the Bar-Yet Again”By Christopher Parker

“The Beatles Raise the Bar-Yet Again” by Christopher Parker I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, Parker, everyone knows that 1967’s Sgt. Pepper‘s Lonely Hearts Club Band is the Beatles’ greatest album and in fact the greatest album of all time. Nope. No way. I beg to differ. In my humble opinion, 1966’s Revolver, the Beatles album released the year before Sgt. Pepper, is the greatest. Why, you ask? In many ways, Revolver was the beginning of a new era, not only in the career of the Beatles, but in the ever-changing world of rock & roll. The world’s greatest rock band was beginning to tire of the endless touring amidst the chaos of Beatlemania. The constant battling against hordes of screaming fans, and a life lived being jostled and shoved from one hotel room to another were becoming more than tiresome. In addition, during a concert, the volume of screams often exceeded 120 decibels-approximately the same noise level as one would be exposed to if he were standing beside a Boeing 747 during takeoff. No one was listening to their music, and consequently, they were beginning to feel like, as John Lennon would later say, ‘waxworks’ or ‘performing fleas.’ Revolver signals a change from the ‘She Loves You’ era-relatively simple songs of love and relationships- to a new era of songs designed to be listened to. These were songs that could never be played at a live concert. They were creations-works of art-songs that were created to be appreciated and discussed-not to elicit screams from teenage girls. -

17 Cut and Run EP- by ECMO (Ozone Records)

19 Nicolette “Ohsay,NaNa” 18 Depth Charge “Depth Charge vs Silver Fox” 17 Cut and Run EP- by ECMO (Ozone records) 16 Badman MDX “Come with me” 15 Orbital “Midnight or choice” 14 Rebel MC “Black meaning good” 13 Nightmares on Wax “A case of Funk” 11 Eon “Fear mind killer” 10 Blapps Posse “Don't hold back” 9 State of Mind “Is that it?” 7 Cookie Watkins “I'm attracted to you” 6 Oceanic “Insanity” 5 Outlander “Vamp” 4 Bugcann “Plastic Jam” 3 Utah Saints “What can you do?” 2 DSK “What would we do?” 1 Prodigy “Charlie says” THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT:-____________________________ -Witch Doctor “Sunday afternoon” (Remix) -DCBA “Acid bitch” (Colin Dale dtd 26.08) -Mellow House “The Flower” TONYMONSON;- THE “SWEET RHYTHYMS CHART”:-31.08.1991 25 Reach “Sooner or later” 23 Sable Jeffries “Open your heart” 21 Boyzn'Hood (Force one network) “Spirit” 20 (CD) Le Genre 19 Cheryl Pepsi Riley “Ain't no way” 12 Pride and Politic “Hold on” 11 Phyllis Hyman “Prime of my life” 10 De Bora “Dream about you” 9 Frankie Knuckles “Rain falls” 8 Your's Truly “Come and get it” 7 Mica Parris “Young Soul Rebels” 6 Jean Rice Your'e a victim” (remix) 5 Pinkie “Looking for love” 4 Young Disciples “Talking what I feel” COLIN DALE;- THE “ABSTRACT DANCE SHOW”:-02.09.1991 1 Bizarre,Inc (Brand new) “Raise me” 2 12” on white label from deejay Trance “Let there be house” 3 IE Records - Reel-to-Real “We are EE” 4 Underground Music movement “ Voice of the rave” (from Italy) Electronic- from PTL 5 Exclusive on Acetate 12” from Virtual Reality “Here” 6 12” called Aah - Really hardcore -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Video Game Systems Uncovered

Everything You Ever Wanted To Know About... VIDEO GAMES But Never Dared To Ask! Introduction: 1 With the holidays quickly approaching the odds are you will be purchasing some type of video game system. The majority of U.S. households currently have at least one of these systems. With the ever changing technology in the video world it is hard to keep up with the newest systems. There is basically a system designed for every child’s needs, ranging from preschool to young adult. This can overwhelming for parents to choose a system that not only meets your child’s needs but also gives us the best quality system for our money. With the holidays coming that means many retailers will be offering specials on video game systems and of course the release of long awaited games. Now is also the time you can purchase systems in bundles with games included. Inside you will learn about all of these topics as well as other necessities and games to accompany to recent purchase. What you’ll find here: 2 In this ebook you will learn about console and portable video game systems, along with the accessories available. You will also find how many games each system has to offer. You will get an in depth look at the pro’s and con’s of each current system available in stores today, and the upcoming systems available in the near future. As a concerned parent you should also be aware of the rating label of the games and what the rating exactly means. -

MTO 23.2: Lafrance, Finding Love in Hopeless Places

Finding Love in Hopeless Places: Complex Relationality and Impossible Heterosexuality in Popular Music Videos by Pink and Rihanna Marc Lafrance and Lori Burns KEYWORDS: Pink, Rihanna, music video, popular music, cross-domain analysis, relationality, heterosexuality, liquid love ABSTRACT: This paper presents an interpretive approach to music video analysis that engages with critical scholarship in the areas of popular music studies, gender studies and cultural studies. Two key examples—Pink’s pop video “Try” and Rihanna’s electropop video “We Found Love”—allow us to examine representations of complex human relationality and the paradoxical challenges of heterosexuality in late modernity. We explore Zygmunt Bauman’s notion of “liquid love” in connection with the selected videos. A model for the analysis of lyrics, music, and images according to cross-domain parameters ( thematic, spatial & temporal, relational, and gestural ) facilitates the interpretation of the expressive content we consider. Our model has the potential to be applied to musical texts from the full range of musical genres and to shed light on a variety of social and cultural contexts at both the micro and macro levels. Received December 2016 Volume 23, Number 2, June 2017 Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory [1.1] This paper presents and applies an analytic model for interpreting representations of gender, sexuality, and relationality in the words, music, and images of popular music videos. To illustrate the relevance of our approach, we have selected two songs by mainstream female artists who offer compelling reflections on the nature of heterosexual love and the challenges it poses for both men and women. -

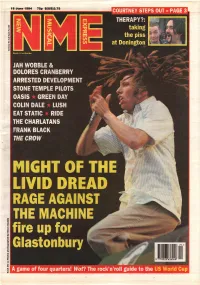

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD.