THE WRITE CHOICE by Spencer Rupert a Thesis Presented to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn Unity3d Programming with Unityscript Suvak Also Available: ONLINE

Learn Unity3D Programming with UnityScript TECHNOLOGy iN ACtiON™ earn Unity Programming with UnityScript is your step-by-step Also available: Lguide to learning to make your first Unity games using UnityScript. Learn You will move from point-and-click components to fully customized features. You need no prior programming knowledge or any experience with other design tools such as PhotoShop or Illustrator - Unity3D Learn you can start from scratch making Unity games with what you’ll learn Unity3D in this book. Through hands-on examples of common game patterns, you’ll learn and apply the basics of game logic and design. You will gradually become comfortable with UnityScript syntax, at each point having everything explained to you clearly and concisely. Many beginner Programming Programming programming books refer to documentation that is too technically abstract for a beginner to use - Learn Unity Programming with UnityScript will teach you how to read and utilize those resources to hone your skills, and rapidly increase your knowledge in Unity game development. with UnityScript You’ll learn about animation, sound, physics, how to handle user interaction and so much more. Janine Suvak has won awards for her game development and is ready to show you how to start your journey as a game developer. The Unity3D game engine is flexible, Unity’s JavaScript for Beginners cross-platform, and a great place to start your game development with adventure, and UnityScript was made for it - so get started game programming with this book today. UnityScript CREATE EXcITING UNITY3D GAMES WITH UNITYScRIPT Suvak ISBN 978-1-4302-6586-3 54499 Shelve in Macintosh/General User level: Beginning 9781430 265863 SOURCE CODE ONLINE www.apress.com Janine Suvak For your convenience Apress has placed some of the front matter material after the index. -

A Producer's Handbook

DEVELOPMENT AND OTHER CHALLENGES A PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK by Kathy Avrich-Johnson Edited by Daphne Park Rehdner Summer 2002 Introduction and Disclaimer This handbook addresses business issues and considerations related to certain aspects of the production process, namely development and the acquisition of rights, producer relationships and low budget production. There is no neat title that encompasses these topics but what ties them together is that they are all areas that present particular challenges to emerging producers. In the course of researching this book, the issues that came up repeatedly are those that arise at the earlier stages of the production process or at the earlier stages of the producer’s career. If not properly addressed these will be certain to bite you in the end. There is more discussion of various considerations than in Canadian Production Finance: A Producer’s Handbook due to the nature of the topics. I have sought not to replicate any of the material covered in that book. What I have sought to provide is practical guidance through some tricky territory. There are often as many different agreements and approaches to many of the topics discussed as there are producers and no two productions are the same. The content of this handbook is designed for informational purposes only. It is by no means a comprehensive statement of available options, information, resources or alternatives related to Canadian development and production. The content does not purport to provide legal or accounting advice and must not be construed as doing so. The information contained in this handbook is not intended to substitute for informed, specific professional advice. -

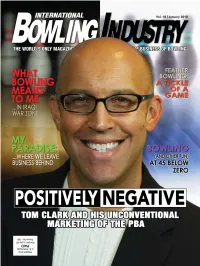

Freeze Frame by Lydia Rypcinski 8 Victoria Tahmizian Bowling and Other [email protected] Fun at 45 Below Zero

THE WORLD'S ONLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED EXCLUSIVELY TO THE BUSINESS OF BOWLING CONTENTS VOL 18.1 PUBLISHER & EDITOR Scott Frager [email protected] Skype: scottfrager 6 20 MANAGING EDITOR THE ISSUE AT HAND COVER STORY Fred Groh More than business Positively negative [email protected] Take a close look. You want out-of-the-box OFFICE MANAGER This is a brand new IBI. marketing? You want Tom Patty Heath By Scott Frager Clark. How his tactics at [email protected] PBA are changing the CONTRIBUTORS way the media, the public 8 Gregory Keer and the players look Lydia Rypcinski COMPASS POINTS at bowling. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Freeze frame By Lydia Rypcinski 8 Victoria Tahmizian Bowling and other [email protected] fun at 45 below zero. By Gregory Keer 28 ART DIRECTION & PRODUCTION THE LIGHTER SIDE Designworks www.dzynwrx.com A feather in your 13 (818) 735-9424 cap–er, lane PORTFOLIO Feather bowling’s the FOUNDER Allen Crown (1933-2002) What was your first game where the balls job, Cathy DeSocio? aren’t really balls, there are no bowling shoes, 13245 Riverside Dr., Suite 501 Sherman Oaks, CA 91423 and the lanes aren’t even 13 (818) 789-2695(BOWL) flat. But people come What was your first Fax (818) 789-2812 from miles around, pay $40 job, John LaSpina? [email protected] an hour, and book weeks in advance. www.BowlingIndustry.com 14 HOTLINE: 888-424-2695 What Bowling 32 Means to Me THE GRAPEVINE SUBSCRIPTION RATES: One copy of Two bowling International Bowling Industry is sent free to A tattoo league? every bowling center, independently owned buddies who built a lane 20 Go ahead and laugh but pro shop and collegiate bowling center in of their own when their the U.S., and every military bowling center it’s a nice chunk of and pro shop worldwide. -

Images of Aggression and Substance Abuse in Music Videos : a Content Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis Monica M. Escobedo San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Escobedo, Monica M., "Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis" (2009). Master's Theses. 3654. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.qtjr-frz7 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OF AGGRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE IN MUSIC VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Monica M. Escobedo May 2009 UMI Number: 1470983 Copyright 2009 by Escobedo, Monica M. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Representations of Women in Music Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1999 Creativity Or Collusion?: Representations of Women in Music Videos Jan E. Urbina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Urbina, Jan E., "Creativity Or Collusion?: Representations of Women in Music Videos" (1999). Master's Theses. 4125. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4125 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATIVITYOR COLLUSION?: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN INMUSIC VIDEOS by Jan E. Urbina A Thesis Submittedto the Facuhy of The GraduateCollege in partial folfitlment of the requirementsfor the Degree of Master of Arts Departmentof Sociology WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1999 Copyright by Jan E. Urbina 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are certain individuals that touch our lives in profound and oftentimes unexpected ways. When we meet them we feel privileged because they positively impact our lives and help shape our futures, whether they know it or not. These individuals stand out as exceptional in our hearts and in our memories because they inspire us to aim high. They support our dreams and goals and guide us toward achieving them They possess characteristics we admire, respect, cherish, and seekto emulate. These individuals are our mentors, our role models. Therefore, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to the outstanding members ofmy committee, Dr. -

MARGARET KAMINSKI 2354 Ewing Street, Los Angeles, CA 90039 646.207.8652 • [email protected]

MARGARET KAMINSKI 2354 Ewing Street, Los Angeles, CA 90039 646.207.8652 • [email protected] EXPERIENCE Nickelodeon, Los Angeles, CA 2016 – Present Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Awards (2019) Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Sports Awards (2018) Writer, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe Awards (2018) Writers’ Assistant, Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards (2017) Writers’ Assistant, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe SPorts Awards (2017) Writers’ Assistant, NiCkelodeon Kids’ ChoiCe SPorts Awards (2016) Above Average Productions, Los Angeles, CA January 2018 – Present Freelance Writer Live From WZRD, Warner Media/VRV, Los Angeles, CA November 2018 – MarCh 2019 Staff Writer Scholastic’s Choices Magazine, New York, New York Video Producer, Story Editor MarCh 2018 – Present Freelance Writer February 2015 – Present Assistant Editor, Managing Editor of Teaching Resources May 2012 – February 2015 SKOOGLE Pilot (All That Reboot), PoCket.WatCh, Los Angeles, CA April 2018 – August 2018 Contributing Writer (punch-up) E! Live from the Red Carpet, Los Angeles, CA August 2017 – November 2018 August 2017 – Present Writer The 2018 PeoPle’s ChoiCe Awards The 2018 Primetime Emmy Awards The 2017 Primetime Emmy Awards The 2017 AmeriCan MusiC Awards The 2018 Golden Globes The 2018 SCreen ACtors Guild Awards The 2018 Grammy Awards MTV Movie + TV Awards Pre-Show, Los Angeles, CA May 2018 – June 2018 Writer PotterCon/Wizard U., National/Touring July 2012 – January 2018 Executive Producer Fallen For You: Pilot, Los Angeles, CA DeCember 2016 Writers’ Assistant Collier.Simon, Los Angeles, CA February 2016 – Present Freelance Writer Masthead Media, New York, NY SePtember 2015 – February 2016 Freelance Writer PMK•BNC (Vowel), New York, NY MarCh 2015 – SePtember 2015 Freelance Writer EDUCATION Barnard College, Columbia University, B.A. -

Feature Film Screenwriter's Workbook

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 A GUIDE TO FEATURE FILM WRITING A Screenwriter’s Workbook & Reference Guide Compiled by Joe T. Velikovsky 2011 Published: 1995, 1998, 2003. This work is intended as an academic review of the literature and theory in the field of Feature Film screenwriting. It is not intended for sale. Wherever possible, please buy and read any or all of the texts referenced within. P a g e | 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................................5 A VERY BRIEF HISTORY OF SCREENPLAY MANUALS .........................................................................6 WHAT IS A SCREENPLAY? .................................................................................................................................7 AN OVERVIEW OF “THE SCREENWRITING PROCESS/STEPS” .......................................................9 WHERE TO START? (WITH `FILM STORY IDEAS’) ............................................................................. 10 THEME ..................................................................................................................................................................... 11 THE CREATIVE PROCESS ................................................................................................................................ 12 THE GREEK LEGACY: 3-ACT STORY STRUCTURE .............................................................................. 13 THE PREMISE ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Cinematographer As Storyteller How Cinematography Conveys the Narration and the Field of Narrativity Into a Film by Employing the Cinematographic Techniques

Cinematographer as Storyteller How cinematography conveys the narration and the field of narrativity into a film by employing the cinematographic techniques. Author: Babak Jani. BA Master of Philosophy (Mphil): Art and Design University of Wales Trinity Saint David. Swansea October 2015 Revised January 2017 Director of Studies: Dr. Paul Jeff Supervisor: Dr. Robert Shail This research was undertaken under the auspices of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David and was submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of a MPhil in the Faculty of Art and Design to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David. Cinematographer as Storyteller How cinematography conveys the narration and the field of narrativity into a film by employing the cinematographic techniques. Author: Babak Jani. BA Master of Philosophy (Mphil): Art and Design University of Wales Trinity Saint David. Swansea October 2015 Revised January 2017 Director of Studies: Dr. Paul Jeff Supervisor: Dr. Robert Shail This research was undertaken under the auspices of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David and was submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of a MPhil in the Faculty of Art and Design to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David. This page intentionally left blank. 4 The alteration Note: The alteration of my MPhil thesis has been done as was asked for during the viva for “Cinematographer as Storyteller: How cinematography conveys narration and a field of narrativity into a film by employing cinematographic techniques.” The revised thesis contains the following. 1- The thesis structure had been altered to conform more to an academic structure as has been asked for by the examiners. -

1Q12 IPG Cable Nets.Xlsm

Independent Programming means a telecast on a Comcast or Total Hours of Independent Programming NBCUniversal network that was produced by an entity Aired During the First Quarter 2012 unaffiliated with Comcast and/or NBCUniversal. Each independent program or series listed has been classified as new or continuing. 2061:30:00 Continuing Independent Series and Programming means series (HH:MM:SS) and programming that began prior to January 18, 2011 but ends on or after January 18, 2011. New Independent Series and Programming means series and programming renewed or picked up on or after January 18, 2011 or that were not on the network prior to January 18, INDEPENDENT PROGRAMMING Independent Programming Report Chiller First Quarter 2012 Network Program Name Episode Name Initial (I) or New (N) or Primary (P) or Program Description Air Date Start Time* End Time* Length Repeat (R)? Continuing (C)? Multicast (M)? (MM/DD/YYYY) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 01:00:00 02:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 02:30:00 04:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 08:00:00 09:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 09:30:00 11:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 11:00:00 12:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER -

295 Fall 2021

CTPR 295 Cinematic Arts Laboratory 4 Units Fall 2021 Concurrent enrollment: CTPR 294 Directing in Television, Fiction, and Documentary Silver/Section#18482 Meeting times: Producing/Cinematography: Fridays, 9:00-11:50am Editing/ Sound: Fridays, 1:00-3:50pm Producing Laboratory (SCA 214 / SCA 356) Instructor: Stephen Gibler Office Hours: by appointment SA: Kayla Sun Cinematography Laboratory (SCE STG #1) Instructor: Savannah Bloch Office Hours: by appointment SA: Luke Harris Editing Laboratory (SCA B120 / SCA 356) Instructor: Avi Glick Office Hours: by appointment SA: Alessia Crucitelli Sound Laboratory (SCA 209) Instructor: Ryan Vaughan Office Hours: by appointment SA: Kelly Osmolski Important Phone Numbers: * NO CALLS AFTER 9:00pm * SCA Labs (213) 740-3981 Help Desk (213) 8212638 Front Desk (213) 740-3981 Tony Bushman (213) 740-2470 Assistant Post Production Manager [email protected] 1 Equipment (Camera) (213) 821-0951 Equipment (Lights) (213) 740-2898 Equipment (sound) (213) 7407-7700 Joe Wallenstein (213) 740-7126 Student Prod. Office - SPO (213) 740-2895 Prod. Faculty Office (213) 740-3317 Campus Cruiser (213) 7404911 THIS SYLLABUS DOES NOT TAKE INTO ACCOUNT RESTRICTIONS OR REQUIREMENTS THAT MAY BE IN PLACE DUE TO THE CHRONA VIRUS AT THE BEGINNING OF THE FALL SEMESTER 2021. CHANGES WILL BE MADE TO INCLUDE THESE AS REQUIRED WHEN THE SEMESTER STARTS Course Structure and Schedule: CTPR 295 consists of four laboratories which, in combination, introduce Cinematic Arts Film and Television Production students to major disciplines of contemporary cinematic practice. Students will learn the basic technology, computer programs, and organizational principles of the four course disciplines that are necessary for the making of a short film. -

The Spectral Incursion

THE SPECTRAL INCURSION JOHN ROGERS AND SHAWN MERWIN Adventure Designer Adventure Code: CCC-BMG-CORE03-01 Optimized For: APL 1 As Melvaunt rebuilds after the devastation wrought by the modron and orc attacks, the planar portal outside the city walls continues to worry everyone in the City of a Thousand Forges. A closer examination of the portal is needed, and brave adventurers are asked to help be part of the reconnaissance team. A four-hour adventure for 1st - 4th level characters Sample file Producer: Baldman Games Development and Editing: Shawn Merwin Proofing and Layout: Encoded Designs Organized Play: Chris Lindsay D&D Adventurers League Wizards Team: Adam Lee, Chris Lindsay, Mike Mearls, Matt Sernett D&D Adventurers League Administrators: Lysa Chen, Bill Benham, Travis Woodall, Claire Hoffman, Greg Marks, Alan Patrick DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2018 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. -

Christy Marx

Write Your Way Into Animation and Games Write Your Way Into Animation and Games Create a Writing Career in Animation and Games Christy Marx AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK © 2010 Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, fur- ther information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organiza- tions such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treat- ment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluat- ing and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.