MTO 23.2: Lafrance, Finding Love in Hopeless Places

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn Unity3d Programming with Unityscript Suvak Also Available: ONLINE

Learn Unity3D Programming with UnityScript TECHNOLOGy iN ACtiON™ earn Unity Programming with UnityScript is your step-by-step Also available: Lguide to learning to make your first Unity games using UnityScript. Learn You will move from point-and-click components to fully customized features. You need no prior programming knowledge or any experience with other design tools such as PhotoShop or Illustrator - Unity3D Learn you can start from scratch making Unity games with what you’ll learn Unity3D in this book. Through hands-on examples of common game patterns, you’ll learn and apply the basics of game logic and design. You will gradually become comfortable with UnityScript syntax, at each point having everything explained to you clearly and concisely. Many beginner Programming Programming programming books refer to documentation that is too technically abstract for a beginner to use - Learn Unity Programming with UnityScript will teach you how to read and utilize those resources to hone your skills, and rapidly increase your knowledge in Unity game development. with UnityScript You’ll learn about animation, sound, physics, how to handle user interaction and so much more. Janine Suvak has won awards for her game development and is ready to show you how to start your journey as a game developer. The Unity3D game engine is flexible, Unity’s JavaScript for Beginners cross-platform, and a great place to start your game development with adventure, and UnityScript was made for it - so get started game programming with this book today. UnityScript CREATE EXcITING UNITY3D GAMES WITH UNITYScRIPT Suvak ISBN 978-1-4302-6586-3 54499 Shelve in Macintosh/General User level: Beginning 9781430 265863 SOURCE CODE ONLINE www.apress.com Janine Suvak For your convenience Apress has placed some of the front matter material after the index. -

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

Fairfaxfairfax Areasareas Ofof Burkeburke

ServingServing Camps & Schools FairfaxFairfax AreasAreas ofof BurkeBurke Author Russ Banham is spending the week touring the county in support of his latest insideinside book, ‘The Fight for Fairfax.’ Classified, Page 18 Classified, ❖ Sports, Page 12 ❖ Schools Switch From PTA Calendar, Page 8 To PTO News, Page 3 Olympic Effort County For Local Skaters Sports, Page 12 Requested in home 9-25-09 home in Requested Time sensitive material. sensitive Time Attention Postmaster: Attention Scribe #86 PERMIT Martinsburg, WV Martinsburg, PAID News, Page 3 Postage U.S. PRSRT STD PRSRT Photo by Justin Fanizzi/The Connection www.ConnectionNewspapers.comSeptember 24-30, 2009 Volume XXIII, Number 38 online at www.connectionnewspapers.comFairfax Connection ❖ September 24-30, 2009 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Fairfax Connection ❖ September 24-30, 2009 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Fairfax Connection Editor Michael O’Connell News 703-778-9416 or [email protected] Fairfax — An Author’s Muse Falling Russ Banham writes For Books about post-World War Literary event II history of county. expands beyond GMU Campus. By Justin Fanizzi The Connection by Photo By Justin Fanizzi The Connection uss Banham has just about seen it all in his 55 years. He was on Fanizzi Justin or the past decade, the Fall for Rthe field after the New York Mets Fthe Book Festival has provided won the 1973 Major League the Fairfax community with a Baseball National League Championship first rate literary experience. Now in Series. He has been commissioned by an its 11th year, festival staff has a big- iconic American family to write a biogra- /The Connection ger goal in mind: to bring that same phy about their patriarch, Henry Ford, and experience to the entire Washington, his circle of friends includes former “Brady D.C. -

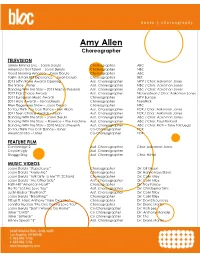

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

The Best Totally-Not-Planned 'Shockers'

Style Blog The best totally-not-planned ‘shockers’ in the history of the VMAs By Lavanya Ramanathan August 30 If you have watched a music video in the past decade, you probably did not watch it on MTV, a network now mostly stuck in a never-ending loop of episodes of “Teen Mom.” This fact does not stop MTV from continuing to hold the annual Video Music Awards, and it does not stop us from tuning in. Whereas this year’s Grammys were kind of depressing, we can count on the VMAs to be a slightly morally objectionable mess of good theater. (MTV has been boasting that it has pretty much handed over the keys to Miley Cyrus, this year’s host, after all.) [VMAs 2015 FAQ: Where to watch the show, who’s performing, red carpet details] Whether it’s “real” or not doesn’t matter. Each year, the VMAs deliver exactly one ugly, cringe-worthy and sometimes actually surprising event that imprints itself in our brains, never to be forgotten. Before Sunday’s show — and before Nicki Minaj probably delivers this year’s teachable moment — here are just a few of those memorable VMA shockers. 1984: Madonna sings about virginity in front of a blacktie audience It was the first VMAs, Bette Midler (who?) was co-hosting and the audience back then was a sea of tux-wearing stiffs. This is all-important scene-setting for a groundbreaking performance by young Madonna, who appeared on the top of an oversize wedding cake in what can only be described as head-to-toe Frederick’s of Hollywood. -

Statement on the Dangers of Guardianship in Response to Britney Spears’S Testimony

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MEDIA CONTACT: Elizabeth Seaberry June 24, 2021 Communications Specialist Disability Rights Oregon Email: [email protected] Mobile: 503.444.0026 Statement on the dangers of guardianship in response to Britney Spears’s testimony Portland, Oregon—Today, Disability Rights Oregon Executive Director Jake Cornett issued the following statement in response to the Britney Spears’s testimony yesterday regarding her conservatorship. Statement from Jake Cornett, Executive Director, Disability Rights Oregon As Britney Spears’s case illustrates, one of the most restrictive things that can happen to a person is having a conservator or guardian be given the power to make crucial life decisions for them. Conservatorships or guardianships take away an individual’s right to make decisions about all aspects of their life, including where they live, what healthcare they get, and how they spend their time and money. Alarmingly, these enormous changes can be made while the person has little to no voice in the process or the chance to object. And conservatorships or guardianships can last a lifetime. Conservatorships and guardianships should be used as little as possible and truly as a last resort. Instead, less restrictive alternatives should be used, alternatives that allow a person to retain as much autonomy over their own life and independence as possible. Whether under conservatorship or guardianship or not, people with disabilities should have optimal freedom, independence, and the basic right to live the life that they choose -

Committee Oks Bergin's As Landmark

BEVERLYPRESS.COM INSIDE • WeHo considers budget. pg. 3 Partly cloudy, • Alan Arkin with highs in honored pg. 12 the mid 70s Volume 29 No. 24 Serving the Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Hancock Park and Wilshire Communities June 13, 2019 La Brea Tar Pits next on Thousands #JustUnite in West Hollywood Museum Row revamp n Organizers will now look ahead to next By edwin folven ed is poised to undergo major year’s landmark 50th changes in the coming years. Black liquid tar has been bub- Dr. Lori Bettison-Varga, presi- anniversary of Pride bling up through the Earth’s surface dent and director of the Natural near present-day Wilshire History Museums of Los Angeles By luke harold Boulevard and Curson Avenue for County, which oversees operations millions of years. With that history at the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum Under the theme #JustUnite, and its scientific importance in (formerly the George C. Page thousands of people attended the mind, the famous site where La 49th annual LA Pride festival Brea Tar Pits and Museum is locat- See Tar Pits page 26 and parade June 8-9 in West Hollywood. The celebration started Friday with a free ceremony and concert in West Hollywood Park head- lined by Paula Abdul. Festival- goers flooded the park and San Vicente Boulevard Saturday and Sunday to see a musical lineup photo by Luke Harold including Meghan Trainor, Pride was on parade Sunday morning, with local council members, law Ashanti and Years & Years. enforcement, corporate sponsors and other groups riding in floats. “Pride has been something I’ve wanted to play for a long just have a good time.” Angeles City Councilman Mitch time,” said Saro, a recording The annual Pride events have O’Farrell on a float during artist who performed in the Pride become a joyous celebration Sunday’s parade. -

1 Court of Appeal Found No Love for Topshop Tank

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK Court of Appeal found no love for Topshop tank: theimage right that dare not speak its name Susan Fletcher Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Central Lancashire Justine Mitchell Associate Lecturer in Law, University of Central Lancashire Subject:Passing Off. Other related subjects: Torts. Image rights.Personalityrights.Publicityrights.Passing off. Tradeconnections.Intellectual property. Keywords:passing off, image rights, personality rights, publicity rights, trade marks, goodwill, misrepresentation, merchandising, endorsements, English law, comparative law, unfair competition, freeriding, unjust enrichment, dilution, monopoly, social media, photograph, Rihanna, Topshop, Fenty, Arcadia Abstract:This article contains an analysis of the first instance and appeal decisions of the “Rihanna case”.In particular, the authors consider the substantive law of passing off in the context of the unauthorised use of a celebrity's image on a Topshop tank vest top. This is followed by a discussionof the consequences of the caseforcelebrities, consumers and stakeholders in theentertainmentand fashion industries. Every time you see me it's a different colour, a different shape, a different style. ....because it really...I/we just go off of instinct. Whatever we feel that very moment, we just go for it. Creatively, fashion is another world for me to get my creativity out.12 1Rihanna quote from the Talk That Talk music video available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVTKxwO2UnU -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Images of Aggression and Substance Abuse in Music Videos : a Content Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis Monica M. Escobedo San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Escobedo, Monica M., "Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis" (2009). Master's Theses. 3654. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.qtjr-frz7 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OF AGGRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE IN MUSIC VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Monica M. Escobedo May 2009 UMI Number: 1470983 Copyright 2009 by Escobedo, Monica M. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Jubliäums-LEA Lässt Stars Und Promis Feiern Medienmogul Beierlein Für Lebenswerk Geehrt

5. Live Entertainment Award in der neuen O2 World Hamburg Jubliäums-LEA lässt Stars und Promis feiern Medienmogul Beierlein für Lebenswerk geehrt Zum fünften Mal wurden am Donnerstag in Hamburg die Live Entertainment Awards (LEA) verliehen, mit denen die deutsche Konzert- und Showbranche herausragende Leistungen von Veranstaltern, Künstlermanagern, Konzertagenten und Spielstätten- betreibern würdigt. Der wichtigste Preis für ein Lebenswerk im Musikgeschäft ging an den 80-jährigen Münchner Medienmanager und „Unterhalter der Nation“ – Hans R. Beierlein. Dass auch das Veranstaltungsgewerbe inzwischen von der Wirtschaftskrise gebeutelt wird und 2009 – nach mehreren Jahren kontinuierlicher Umsatzzuwächse – erstmals Einbußen verzeichnen musste, davon war in der ehemaligen Color Line Arena nichts zu spüren. Die neue O2 World Hamburg erlebte nicht nur ihre Feuertaufe und Premiere, sondern auch eine Livebranche, die sich in einer dreieinhalbstündigen glamourösen Gala selbst feierte – und die hierzu reichlich Prominenz und Stars aus dem Showbusiness auf den roten Teppich lud: Da stellten sich Peter Maffay, die Scorpions und Christina Stürmer ebenso dem Blitzlichtgewitter wie Roger Cicero, Soulsängerin Joy Denalane, Reamonn-Sänger Rea Garvey, Comedian Hans Werner Olm oder die Musiker von Silbermond und Tomte. Weiter auf dem Parkett gesehen: die HSV-Profis Jerome Boateng und Dennis Aogo, die Boxer Juan Carlos Gomez und Kohren Gevor, Starmodel Fiona Erdmann, die Sänger Michy Reincke, Tom Gaebel, Lotto King Karl, Carsten Pape, Kai Wingenfelder, Hans