Marketing Violent Entertainment to Children: a Review of Self-Regulation and Industry Practices in the Motion Picture, Music Recording & Electronic Game Industries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn Unity3d Programming with Unityscript Suvak Also Available: ONLINE

Learn Unity3D Programming with UnityScript TECHNOLOGy iN ACtiON™ earn Unity Programming with UnityScript is your step-by-step Also available: Lguide to learning to make your first Unity games using UnityScript. Learn You will move from point-and-click components to fully customized features. You need no prior programming knowledge or any experience with other design tools such as PhotoShop or Illustrator - Unity3D Learn you can start from scratch making Unity games with what you’ll learn Unity3D in this book. Through hands-on examples of common game patterns, you’ll learn and apply the basics of game logic and design. You will gradually become comfortable with UnityScript syntax, at each point having everything explained to you clearly and concisely. Many beginner Programming Programming programming books refer to documentation that is too technically abstract for a beginner to use - Learn Unity Programming with UnityScript will teach you how to read and utilize those resources to hone your skills, and rapidly increase your knowledge in Unity game development. with UnityScript You’ll learn about animation, sound, physics, how to handle user interaction and so much more. Janine Suvak has won awards for her game development and is ready to show you how to start your journey as a game developer. The Unity3D game engine is flexible, Unity’s JavaScript for Beginners cross-platform, and a great place to start your game development with adventure, and UnityScript was made for it - so get started game programming with this book today. UnityScript CREATE EXcITING UNITY3D GAMES WITH UNITYScRIPT Suvak ISBN 978-1-4302-6586-3 54499 Shelve in Macintosh/General User level: Beginning 9781430 265863 SOURCE CODE ONLINE www.apress.com Janine Suvak For your convenience Apress has placed some of the front matter material after the index. -

Economic Report on the Screen-Based

PROFILE ECONOMIC REPORT ON THE SCREEN-BASED MEDIA PRODUCTION INDUSTRY IN CANADA 2019 PROFILE ECONOMIC REPORT ON THE SCREEN-BASED MEDIA PRODUCTION INDUSTRY IN CANADA 2019 Prepared for the Canadian Media Producers Association, Department of Canadian Heritage, Telefilm Canada and Association québécoise de la production médiatique Production facts and figures prepared by Nordicity Group Ltd. Profile 2019 is published by the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA) in collaboration with the Department of Canadian Heritage, Telefilm Canada, the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM) and Nordicity. Profile 2019 marks the 23rd edition of the annual economic report prepared by CMPA and its project partners over the years. The report provides an analysis of economic activity in Canada’s screen-based production sector during the period April 1, 2018 to March 31, 2019. It also provides comprehensive reviews of the historical trends in production activity between fiscal years 2009/10 to 2018/19. André Adams-Robenhymer Policy Analyst, Film and Video Policy and Programs Ottawa Susanne Vaas Department of Canadian Mohamad Ibrahim Ahmad 251 Laurier Avenue West, 11th Floor Vice-President, Heritage Statistics and Data Analytics Ottawa, ON K1P 5J6 Corporate & International Affairs 25 Eddy Street Supervisor, CAVCO Gatineau, QC K1A 0M5 Tel: 1-800-656-7440 / 613-233-1444 Nicholas Mills Marwan Badran Email: [email protected] Director, Research Tel: 1-866-811-0055 / 819-997-0055 Statistics and Data Analytics cmpa.ca TTY/TDD: 819-997-3123 Officer, CAVCO Email: [email protected] Vincent Fecteau Toronto https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian- Senior Policy Analyst, 1 Toronto Street, Suite 702 heritage.html Film and Video Policy and Programs Toronto, ON M5C 2V6 Mounir Khoury Tel: 1-800-267-8208 / 416-304-0280 The Department of Canadian Senior Policy Analyst, Email: [email protected] Heritage contributed to the Film and Video Policy and Programs funding of this report. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

Panthera Download Dayz

Panthera download dayz Author Website: .. Guest have the lowest downloadspeeds and will download from our public file servers. Day-Z - How To Install | EPOCH 'PANTHERA' MOD | Simple takes 2 mins . Download dayz commander. Parameters: mod=@Panthera Panthera Map: and does it have epoch in it or need i to download sepretly. Hey Guys, its Milzah here this is just a simple tutorial on how to install Panthera Island. If this helped you how about drop in a sub and a like. Download link for all. Panthera is an unofficial map for DayZ. It was created by a user named IceBreakr. Like other DayZ maps, the island of Panthera is fictional, but. DayZ Panthera ?action=downloads;sa=view;down= ISLA PANTHERA FOR ARMA 2 Version: v Release date: Dec 27 Awesome downloading now, thank you, ill post some screens later of the. Download DayZ here with the free DayZCommander utility and join over Taviana ()DayZ NamalskDayZ LingorDayZ PantheraDayZ. What's in this release: Panthera: Updated to the latest Panthera patch (). INSTRUCTIONS: First of all, download DayZ Commander if you. Hey we are running a quite successfull Dayz Epoch Chernarus Anybody knows where to download Panthera files manually that. Also remember to download the DayZ Epoch mod off of DayZ DayZRP mod, DayZ Epoch , DayZRP Assets and Panthera. A map of Panthera Island for DayZ, showing loot spawns and loot tables. Installing DayZ Epoch Panthera using PlayWithSix Launcher. To start off, go to ?PlaywithSIX to download the launcher. Greetings Arma 2 players! I have been trying for days to download Epoch Panthera Mod through DayzCommander, as i cant find it. -

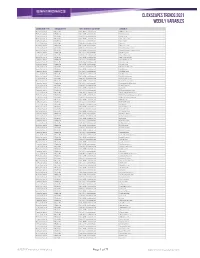

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Permadeath in Dayz

Fear, Loss and Meaningful Play: Permadeath in DayZ Marcus Carter, Digital Cultures Research Group, The University of Sydney; Fraser Allison, Microsoft Research Centre for Social NUI, The University of Melbourne Abstract This article interrogates player experiences with permadeath in the massively multiplayer online first-person shooter DayZ. Through analysing the differences between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ instances of permadeath, we argue that meaningfulness – in accordance with Salen & Zimmerman’s (2003) concept of meaningful play – is a critical requirement for positive experiences with permadeath. In doing so, this article suggests new ontologies for meaningfulness in play, and demonstrates how meaningfulness can be a useful lens through which to understand player experiences with negatively valanced play. We conclude by relating the appeal of permadeath to the excitation transfer effect (Zillmann 1971), drawing parallels between the appeal of DayZ and fear-inducing horror games such as Silent Hill and gratuitously violent and gory games such as Mortal Kombat. Keywords DayZ, virtual worlds, meaningful play, player experience, excitation transfer, risk play Introduction It's truly frightening, like not game-frightening, but oh my god I'm gonna die-frightening. Your hands starts shaking, your hands gets sweaty, your heart pounds, your mind is racing and you're a wreck when it's all over. There are very few games that – by default – feature permadeath as significantly and totally as DayZ (Bohemia Interactive 2013). A new character in this massively multiplayer online first- person shooter (MMOFPS) begins with almost nothing, and must constantly scavenge from the harsh zombie-infested virtual world to survive. A persistent emotional tension accompanies the requirement to constantly find food and water, and a player will celebrate the discovery of simple items like backpacks, guns and medical supplies. -

Images of Aggression and Substance Abuse in Music Videos : a Content Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis Monica M. Escobedo San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Escobedo, Monica M., "Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis" (2009). Master's Theses. 3654. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.qtjr-frz7 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OF AGGRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE IN MUSIC VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Monica M. Escobedo May 2009 UMI Number: 1470983 Copyright 2009 by Escobedo, Monica M. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

Seawood Village Movies

Seawood Village Movies No. Film Name 1155 DVD 9 1184 DVD 21 1015 DVD 300 348 DVD 1408 172 DVD 2012 704 DVD 10 Years 1175 DVD 10,000 BC 1119 DVD 101 Dalmations 1117 DVD 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 DVD 12 Rounds 843 DVD 127 Hours 446 DVD 13 Going on 30 474 DVD 17 Again 523 DVD 2 Days In New York 208 DVD 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 DVD 21 Jump Street 1145 DVD 27 Dresses 1079 DVD 3:10 to Yuma 1124 DVD 30 Days of Night 204 DVD 40 Year Old Virgin 1101 DVD 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 DVD 50 First Dates 117 DVD 6 Souls 1205 DVD 88 Minutes 177 DVD A Beautiful Mind 643 DVD A Bug's Life 255 DVD A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 DVD A Christmas Carol 581 DVD A Christmas Story 506 DVD A Good Day to Die Hard 212 DVD A Knights Tale 848 DVD A League of Their Own 856 DVD A Little Bit of Heaven 1053 DVD A Mighty Heart 961 DVD A Thousand Words 1139 DVD A Turtle's Tale: Sammy's Adventure 376 DVD Abduction 540 DVD About Schmidt 1108 DVD Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter 1160 DVD Across the Universe 812 DVD Act of Valor 819 DVD Adams Family & Adams Family Values 724 DVD Admission 519 DVD Adventureland 83 DVD Adventures in Zambezia 745 DVD Aeon Flux 585 DVD Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 DVD Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 496 DVD Alex & Emma 79 DVD Alex Cross 947 DVD Ali 1004 DVD Alice in Wonderland 525 DVD Alice in Wonderland - Animated 838 DVD Aliens in the Attic 1034 DVD All About Steve 1103 DVD Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 785 DVD Alpha and Omega 970 DVD Alpha Dog 522 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked -

From Simulation to Imitation

SAGXXX10.1177/1046878114542316Simulation & Gamingde Castell et al. 542316research-article2014 Article Simulation & Gaming 2014, Vol. 45(3) 332 –355 From Simulation to Imitation: © 2014 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: Controllers, Corporeality, sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1046878114542316 and Mimetic Play sag.sagepub.com Suzanne de Castell1, Jennifer Jenson2, and Kurt Thumlert2 Abstract Background. We contend that a conceptual conflation of simulation and imitation persists at the heart of claims for the power of game-based simulations for learning. Recent changes in controller-technologies and gaming systems, we argue, make this conflation of concepts more readily apparent, and its significant educational implications more evident. Aim. This article examines the evolution in controller technologies of imitation that support players’ embodied competence, rather than players’ ability to simulate such competence. Digital gameplay undergoes an epistemological shift when player and game interactions are no longer restricted to simulations of actions on a screen, but instead support embodied imitation as a central element of gameplay. We interrogate the distinctive meanings and affordances of simulation and imitation and offer a critical conceptual strategy for refining, and indeed redefining, what counts as learning in and from digital games. Method. We draw upon actor-network theory to identify what is educationally significant about the digitally mediated learning ecologies enabled by imitation- based gaming consoles and controllers. Actor-network theory helps us discern relations between human actors and technical artifacts, illuminating the complex inter-dependencies and inter-actions of the socio-technical support networks too long overlooked in androcentric theories of human action and cognitive psychology. 1University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Canada 2York University, Canada Corresponding Author: Suzanne de Castell, Faculty of Education, University of Ontario Institute of Technology, 11 Simcoe St. -

Reply Comments to Comment 36

Reply Comments to Comment 36. David B. Carroll 19 February 2003 1. Class of Work From Comment #361: Audiovisual works as follows: foreign-language audiovisual works not available for sale in the United States but available for purchase outside the US on DVDs that are regionally encoded to prevent playback on DVD players purchased in the United States. The exemption requested is to permit circumvention of the region coding mechanism. 2. Summary of Argument Additional factual information in support of Comment #36’s initial request for an exemption is submitted. The proposed class is compared against a similar class from Comment #352, which offers some advantages over this class. 3. Factual Support / Legal Arguments 3.1.Evidence of a need to circumvent DVD region coding for works in this class. The Library’s solicitation for comments makes it clear that a demonstration of actual or likely damage is a prerequisite for a successful exemption, rather than an argument based solely on hypothetical or legal grounds. I have collected additional examples of, and documentation for, real-world demand for DVD content unavailable in Region 1 (“R1”) format. 3.1.1. DVD features unavailable on VHS. In rejecting an exemption for circumvention of DVD access controls in 2000, the Library of Congress wrote3: 1 Carroll, David B. Comment #36. 18 Dec 2002. http://www.copyright.gov/1201/2003/comments/036.pdf. 2 Von Lohmann, Fred and Gwen Hinze, Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Gigi Sohn, Public Knowledge. Comment #35. Dec 2002. http://www.copyright.gov/1201/2003/comments/035.pdf. From the comments and testimony presented, it is clear that, at present, most works available in DVD format are also available in analog format (VHS tape) as well..