Counterguerilla Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRATERNITIES Carstens

m _ edseodestt whe sepas the letter @t Maysee flaith Bad pinsw0 *ie aft Us enm tsee UP&U bwad wima-&imips1 ed t 000ta by er ber at whnne *ate fad both,"1110r110119"M mudt without. do usht net bb h h la W Wesatm112,0am has e the "am ofterams esm- * 'Dd him come W she said, and then been Ons in 4 bte" a fee-Illmmme a 4bvn--ai Mgea Sone of the maids of he the at thimrtu ofs0 ase a t be 1T. "evhgo de isn- temporary bath led a m dU- wh See waS esat to each m 1er et the esb- went to gli the mesenger Into the lsser who ghter-h&* 'a wwa hs' blood. wof I usaw m of the two tents of festval she added. bath made o she is ToU-q0-- a , bm his- **m7~TheIlulmef aemin cemnib- "And where Is-the'ma r you." Ie a towar the MareemA, BathM 944Wo baentehodAM LaVIARSIXh et PyM,aw atdtismA ~mmn-y. Adigagoswh.gnot tuigase with a, It was Yvette who answered ber. who stood u whSS anTraR TheI to a 100110 s-m 4101 yeaw ag& Some n"4aa 'Do not hear?' she erled, clapping at-the anddea fduf&panm. Vri mosame be itramarred M' aamhabemPto 8m-I he of a you wRi the harbt t t" eamtr Maes, No. of ts and Is her hands with pleasurw "His people are boy, slay YoeIldn 2, Hity, wt He bringing him up In triumph. Do you hear And at the wonhe preciptated Mise rec"neftd as me at the most sette aGd leg. -

Counterguerrilla Operation

FM 90-8 counterguerrilla operation/ AUGUST 1986 This publication contains technical or operational information that is for official government use only. Distribution is limited to US Government agencies Requests from outside the US Government for release of this publication under the Freedom of Information Act or the Foreign Military Sales Program must be made to: HO TR ADOC, Fort Monroe, VA 23651 ... HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION- Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. FM 90-8 CHAPTER 6. COMBAT SUPPORT Section I. General ............................................ 6-1 II. Reconnaissance and Surveillance Units ............. 6-2 Ill. Fire Support Units ................................. 6-7 CHAPTER 7. COMBAT SERVICE SUPPORT Section I. General ............................................ 7-1 II. Bases ............................................. 7-1 Ill. Use of Assets ...................................... 7-3 APPENDIX A. SUBSURFACE OPERATIONS Section I. General ............................................ A-1 II. Tunneling .......................................... A-2 Ill. Destroying Underground Facilities ................. A-12 APPENDIX B. THE URBAN GUERRILLA Section I. General ............................................ B-1 II. Techniques to Counter the Urban Guerrilla .......... B-2 APPENDIX C. AMBUSH PATROLS Section I. General ............................................ C-1 II. Attack Fundamentals .............................. C-2 Ill. Planning .......................................... -

GREGORY the Natures of War FINAL May 2015

!1 The Natures of War Derek Gregory for Neil 1 In his too short life, Neil Smith had much to say about both nature and war: from his seminal discussion of ‘the production of nature’ in his first book, Uneven development, to his dissections of war in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries in American Empire – where he identified the ends of the First and Second World Wars as crucial punctuations in the modern genealogy of globalisation – and its coda, The endgame of globalization, a critique of America’s wars conducted in the shadows of 9/11. 2 And yet, surprisingly, he never linked the two. He was of course aware of their connections. He always insisted that the capitalist production of nature, like that of space, was never – could not be – a purely domestic matter, and he emphasised that the modern projects of colonialism and imperialism depended upon often spectacular displays of military violence. But he did not explore those relations in any systematic or substantive fashion. He was not alone. The great Marxist critic Raymond Williams once famously identified ‘nature’ as ‘perhaps the most complex word in the [English] language.’ Since he wrote, countless commentators have elaborated on its complexities, but few of them 1 This is a revised and extended version of the first Neil Smith Lecture, delivered at the University of St Andrews – Neil’s alma mater – on 14 November 2013. I am grateful to Catriona Gold for research assistance on the Western Desert, to Paige Patchin for lively discussions about porno-tropicality and the Vietnam war, and to Noel Castree, Dan Clayton, Deb Cowen, Isla Forsyth, Gastón Gordillo, Jaimie Gregory, Craig Jones, Stephen Legg and the editorial collective of Antipode for radically improving my early drafts. -

The North Korean Nuclear Crisis: Past Failures, Present Solutions

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 50 Number 2 A Tribute to the Honorable Michael A. Article 16 Wolff (Winter 2006) 2006 The North Korean Nuclear Crisis: Past Failures, Present Solutions Morse Tan The University of Texas at Austin School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Morse Tan, The North Korean Nuclear Crisis: Past Failures, Present Solutions, 50 St. Louis U. L.J. (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol50/iss2/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW THE NORTH KOREAN NUCLEAR CRISIS: PAST FAILURES, PRESENT SOLUTIONS MORSE TAN* ABSTRACT North Korea has recently announced that it has developed nuclear weapons and has pulled out of the six-party talks. These events do not emerge out of a vacuum, and this Article lends perspective through an interdisciplinary lens that seeks to grapple with the complexities and provide constructive approaches based on this well-researched understanding. This Article analyzes political, military, historical, legal and other angles of this international crisis. Past dealings with North Korea have been unfruitful because other nations do not recognize the ties between North Korean acts and its ideology and objectives. For a satisfactory resolution to the current crisis, South Korea and the United States must maintain sufficient deterrence, focus on multi-lateral and international avenues, and increase the negative and later positive incentives for North Korean compliance with its international obligations. -

FM 3-24.2. Tactics in Counterinsurgency

FM 3-24.2 (FM 90-8, FM 7-98) TACTICS IN COUNTERINSURGENCY APRIL 2009 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release, distribution is unlimited. HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (www.us.army.mil) and General Dennis J. Reimer Training and Doctrine Digital Library at (www.train.army.mil). * FM 3-24.2 (FM 90-8, FM 7-98) Field Manual Headquarters Department of the Army No. 3-24.2 Washington, DC, 21 April 2009 Tactics in Counterinsurgency Contents Page PREFACE ................................................................................................................. viii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... ix Chapter 1 OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT OF COUNTERINSURGENCY ........................... 1-1 Section I—OVERVIEW ............................................................................................. 1-1 Insurgency........................................................................................................... 1-1 Counterinsurgency .............................................................................................. 1-2 Influences on Current Operational Environments ............................................... 1-2 Section II—OPERATIONAL AND MISSION VARIABLES ..................................... 1-3 Operational Variables ......................................................................................... 1-3 Mission Variables ............................................................................................... -

Airpower in Three Wars

AIRPOWER IN THREE WARS GENERAL WILLIAM W. MOMYER USAF, RET. Reprint Edition EDITORS: MANAGING EDITOR - LT COL A. J. C. LAVALLE, MS TEXTUAL EDITOR - MAJOR JAMES C. GASTON, PHD ILLUSTRATED BY: LT COL A. J. C. LAVALLE Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2003 Air University Library Cataloging Data Momyer, William W. Airpower in three wars / William W. Momyer ; managing editor, A. J. C. Lavalle ; textual editor, James C. Gaston ; illustrated by A. J. C. Lavalle–– Reprinted. p. ; cm. With a new preface. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-116-3 1. Airpower. 2. World War, 1939–1945––Aerial operations. 3. Korean War. 1950–1953––Aerial operations. 4. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961–1975––Aerial oper- ations. 5. Momyer, William W. 6. Aeronautics, Military––United States. I. Title. II. Lavalle, A. J. C. (Arthur J. C.), 1940– III. Gaston, James C. 358.4/009/04––dc21 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii TO . all those brave airmen who fought their battles in the skies for command of the air in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PREFACE 2003 When I received the request to update my 1978 foreword to this book, I thought it might be useful to give my perspective of some aspects on the employment of airpower in the Persian Gulf War, the Air War over Serbia (Operation Allied Force), and the war in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom). -

Vietnam War US Army Video Log Michael Momparler Born

Video Log Michael Momparler Vietnam War U.S. Army Born: 03/05/1947 Interviewed on 11/20/2012 Interviewed by: George Jones 00:00:00 Introduction 00:00:23 Michael Momparler’s highest rank was 1st Lieutenant. 00:00:35 Momparler served in III Corps in Vietnam 00:00:45 Momparler was living in College Point, NY when he enlisted in the Army on 4/18/1966. He joined because he was a wild teenager with legal problems and few other options 00:01:45 Momparler discusses first days in the U.S. Army and his thoughts about the experience and the military experiences of other family members; specifically a cousin who suffered the loss of six fellow Marines. 00:03:23 Momparler discusses basic training experiences like using monkey bars, the mile run, and KP. 00:04:40 Momparler discusses being selected for Officer Candidate School - OCS. Mentions the testing and that he was encouraged to tell the interviewing officer that the war in Vietnam should be escalated. Entered OCS at age 19. 00:05:50 Momparler transition from basic training to advanced infrantry training to OCS. 00:06:24 Momparler discusses experiences with the M-14, M-15, and M-16 rifles. 00:07:00 Momparler discusses the experience of Officer Candidate School. 00:10:32 Momparler mentions that one of his commanding officers was in the Bay of Pigs invasion. Discusses the amount of combat experience, or Vietnam experience of his commanding officers at OCS. 00:11:00 Momparler discusses how OCS candidates used the OCS experience to limit their amount of time in the Army or avoid having to serve in Vietnam. -

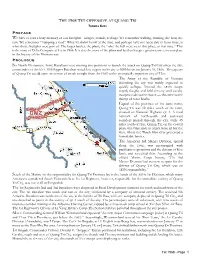

Tet 1968 Draft 2

THOMAS KJOS We have at least a hazy memory of our firefights - images, sounds, feelings. We remember walking, running, the heat, the rain. We remember “humping a load.” What we didn’t know at the time, and perhaps have not been able to learn since, is what those firefights were part of. The larger battles, the plans, the “why the hell were we in that place, at that time.” This is the story of Delta Company at Tet in 1968. It is also the story of the plans and battles that give greater context to our place in the history of the Vietnam war. Six North Vietnamese Army Battalions were moving into positions to launch the attack on Quang Tri City when the elite commandos of the NVA 10th Sapper Battalion struck key targets in the city at 0200 hours on January 31, 1968. The capture of Quang Tri would open an avenue of attack straight from the DMZ to the strategically important city of Hue. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam defending the city was widely expected to quickly collapse. Instead, the ARVN troops stayed, fought, and held the city until cavalry troopers rode to the rescue — this time to the thump of rotor blades. Capital of the province of the same name, Quang Tri was 12 miles south of the DMZ, situated on National Highway QL 1. A road network of north-south and east-west corridors passed through the city. Only 45 miles north of Hue, Quang Tri, on the coastal plain, was vulnerable to attack from all but the west, where the Thach Han river presented a formidable barrier. -

![URL ] Tends to Match up with the Photographs](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7705/url-tends-to-match-up-with-the-photographs-1487705.webp)

URL ] Tends to Match up with the Photographs

archived as http://www.stealthskater.com/Documents/Skeggs_02.doc [pdf] *** last updated 02/13/2005 *** more is at http://www.stealthskater.com/PX.htm#StarChamber From: "Thomas Skeggs" Date: Sun, July 13, 2003 9:47 am To: [email protected] Subject: Philadelphia Photo Hello Mark -- In my old collection of papers, I found a British article called "The Physics of a Flying Saucer" by Ted Roach, an Australian Engineer. (The pictures do not appear in his book). In this article was a brief paragraph on the Philadelphia Experiment. It included 2 photos. The caption reads “The USS Eldridge and the prototype machinery used in the infamous Philadelphia Experiment". There are no credits to these pictures. The article appeared in the now defunct Alien Encounters magazine, September 1997. I don’t know if the pictures are genuine. The description in Chica Bruce’s book [SS: see doc pdf URL ] tends to match up with the photographs. (I attached one photo in JPEG format. I can send the other if you want a copy.) Last week, I ordered some books including The Philadelphia Experiment Murder which you pointed out. Plus I ordered Montauk Revisited and the Pyramids of Montauk. And they arrived today (July 10). I was taken aback by some of the claims made by Preston Nichols. I see what you really mean when he goes off on a tangent. I thought his first book was but too unbelievable. I have only flicked through them. The remote-viewing data points to a scheme where children were being used in the program, and it relates to the strange and disturbing dreams. -

Interactive Qualifying Project the Educational Case for a Simulated Lunar Base

Interactive Qualifying Project The Educational Case for a Simulated Lunar Base By: Justin Linnehan Patrick Nietupski Nicholas Wheeler Advisor: John Wilkes March 11, 2010 1 Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 The New Space Race...................................................................................................................................... 9 The Case for Construction of a Mock Lunar Base in Worcester .................................................................. 29 A Study of the Feasibility of the Proposal: Worcester Science Teacher Reaction ...................................... 43 Educational case .......................................................................................................................................... 51 AIAA Conference ......................................................................................................................................... 55 Doherty High School’s After School Club ....................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Edward Kiker ................................................................................................................................................ 75 N.E.A.M. Expo and Table Top Model ........................................................................................................... 80 Elm Park School .......................................................................................................................................... -

DUE 43 Cover

M4 SHERMAN TYPE 97 CHI-HA The Pacific 1945 STEVEN J. ZALOGA © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com M4 SHERMAN TYPE 97 CHI-HA The Pacific 1945 STEVEN J. ZALOGA © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS Introduction 4 Chronology 8 Design and Development 10 Technical Specifications 21 The Combatants 30 The Strategic Situation 41 Combat 47 Statistics and Analysis 74 Bibliography 78 Index 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Most titles in the Duel series deal with weapons of similar combat effectiveness. But what happens when the weapons of one side are dramatically inferior to those of the other? Could the technological imbalance be overcome by innovative tactics? This title examines such a contest, the US Army’s M4A3 Sherman medium tank against the Japanese Type 97-kai Shinhoto Chi-Ha in the Philippines in 1945. Tank combat in the Pacific War of 1941–45 is not widely discussed. There has long been a presumption that the terrain conditions in many areas, especially the mountainous tropical jungles of the Southwest Pacific and Burma, were not well suited to tank use. Yet the terrain of the Pacific battlefields varied enormously, from the fetid jungles of New Guinea to the rocky coral atolls of the Central Pacific. In many of the critical campaigns of 1944–45, the terrain was suitable for tank use and they became a critical ingredient in the outcome of the fighting. This book examines the largest single armored clash of the Pacific War – on Luzon in the Philippines in January–February 1945. This was the only time that the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) committed an entire armored division against American or British forces. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control.